Last updated: May 14, 2025

Article

Tribal-Federal Collaboration on Gull Egg Harvest

- Tania Lewis, Wildlife Biologist, Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve

- Mary Beth Moss, Tribal Liaison, Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve

- Darlene See, Cultural Program Manager, Hoonah Indian Association

Łingít Homeland

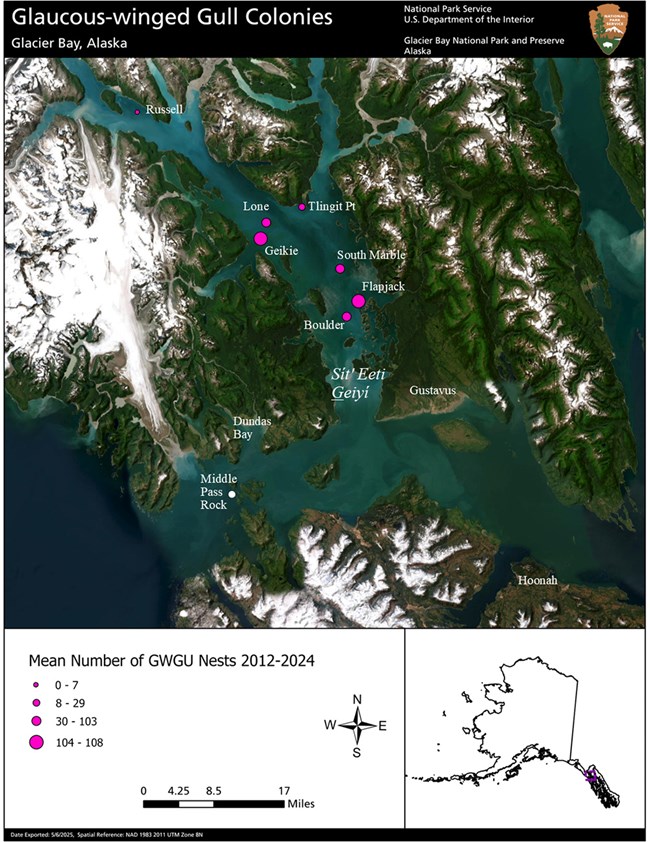

Since time immemorial, the lands and waters now encompassed by Glacier Bay National Park have been Homeland for the clans that comprise the Xunaa Łingít (Goldschmidt and Haas 1998). Oral histories describe a life of abundance in the glacially mediated landscape of S'é Shuyee (Area at the End of the Glacial Silt) before the little ice age drove clans to more protected areas (Dauenhauer and Dauenhauer 1987). Although the Xunaa clans eventually settled a large winter village in what is now Hoonah, Alaska, their hunters returned frequently to witness a glacial retreat that was almost as rapid as its advance. By the mid-1800s, salmon were recolonizing bedrock-stabilized streams in the newly revealed Glacier Bay landscape and diverse wildlife, including an abundance of bird life, had returned (Milner et al. 2011).This new landscape, Sít' Eeti Geiyí (Bay in Place of the Glacier), was particularly suitable for colonial nesting seabirds that preferentially nest in rocky or early successional herbaceous habitats. In particular, glaucous-winged gull populations increased, colonizing the many islands of lower Glacier Bay. Their speckled eggs are treasured spring foods for the Łingít who relish this fresh and nutrient-rich food source after long months of subsisting on preserved fish and meats.

Photo courtesy of the Mills family.

Although data are limited on the level of egg harvest occurring over time, oral histories, including those collected by Hunn and others (2002) suggest that egg harvest was a regular, annual practice for many Huna families well into the 1960s. Members of the 1899 Harriman expedition were treated to a meal of gulls eggs, boiled marmot and seal while in Dundas Bay (Goetzmann and Sloan 1982).

NPS/Mary Beth Moss

By 1965, however, the National Park Service (NPS) began enforcing the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 and related NPS regulations that prohibited egg harvest. It is likely that the Native community of Hoonah was still uncertain as to the exact NPS policy regarding egg collecting as the activity continued at some level into the late 20th century. For example, Schroeder (1995) found that Huna Łingít gull egg harvest, although diminished in intensity, continued throughout all areas of the park well into the 1980s.

The eventual enforcement of these laws and regulations understandably strained relationships between the Huna Łingít and the NPS. The period of estrangement that followed is referred to as “the second little ice age,” by the Huna clans. For decades, Tribal members either gave up traditional activities now considered illegal or “were made criminals for our food” as a letter from the Huna Traditional Council of Elders described those that quietly continued to harvest underground (Juneau Empire, October 22, 1992). Over time, tensions around the Łingít sense of estrangement grew, culminating in what became known as the Peaceful Demonstration—an event held in Bartlett Cove in 1992. During this event, hundreds of Tribal members traveled by seine boats to reassert their right to Homeland. While untrained NPS staff seem not to have fully understood the significance of this event to the Huna people, new cultural resource staff hired shortly thereafter began exploring options for repairing relationships with Tribal partners. In 1997, these individuals designed a workshop focused on collaborating with the Huna Łingít to collect traditional knowledge that might inform park management. During the workshop, Huna Elders described their longing for gull eggs, harbor seals, and mountain goats, noting that gull egg harvest was their primary focus.

In response, park staff initiated a two-pronged study to collect the information required for the thorough environmental analysis required to support egg harvest First, an ethnography of bird egg harvest in Glacier Bay identified historic harvest locations and described traditional harvest practices (Hunn et al. 2002). One year later, U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) biologists used harvest strategies described in the ethnography to model the effects of harvest on a gull egg population at South Marble Island in Glacier Bay (Zador et al. 2006).

In the interim, the Hoonah Indian Association (HIA; the federally recognized Tribal Government) applied for and received a Special Purpose Permit from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) and Cultural Education Permits from the State of Alaska to collect gull eggs at Middle Pass Rock, a nesting area outside park boundaries. To model good faith, the NPS provided logistical support to HIA harvesters in 2001, 2002, and 2003, providing vessel transportation to Middle Pass Rock and assisting with permit applications and reporting requirements. HIA Tribal members harvested eggs in each of these 3 years, although the island yielded fewer than 80 eggs on each trip (HIA files).

Regulations governing the subsistence harvest of migratory birds in Alaska are located in title 50 of the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) in part 92. In 1997, these regulations were amended to allow for spring/summer subsistence harvest of migratory birds by Indigenous inhabitants of specifically identified subsistence harvest areas in Alaska. In the early years following the amendment, harvests were authorized for numerous northern Alaskan communities. The ethnographic data collected by Hunn and others (2002) was also valuable in documenting that egg harvest was a traditional practice in Southeast Alaska. In 2004, the NPS assisted HIA in submitting data to that effect; based on that data, the annual regulations promulgated by the USFWS allowed for the harvest of glaucous-winged gull eggs by the permanent residents of Hoonah in Cross Sound and Icy Strait, but not within Glacier Bay National Park in subsequent years.

In following years, NPS prepared a Legislative Environmental Impact Statement (LEIS) that determined that egg harvest could occur within the park without impacting gull populations or other park resources. Based on these findings, Congress passed legislation in 2014 authorizing harvest of glaucous-winged gull eggs in Glacier Bay National Park (Lewis and Moss 2015).

Regulations governing the subsistence harvest of migratory birds in Alaska are located in title 50 of the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) in part 92. In 1997, these regulations were amended to allow for spring/summer subsistence harvest of migratory birds by Indigenous inhabitants of specifically identified subsistence harvest areas in Alaska. In the early years following the amendment, harvests were authorized for numerous northern Alaskan communities. The ethnographic data collected by Hunn and others (2002) was also valuable in documenting that egg harvest was a traditional practice in Southeast Alaska. In 2004, the NPS assisted HIA in submitting data to that effect; based on that data, the annual regulations promulgated by the USFWS allowed for the harvest of glaucous-winged gull eggs by the permanent residents of Hoonah in Cross Sound and Icy Strait, but not within Glacier Bay National Park in subsequent years.

In following years, NPS prepared a Legislative Environmental Impact Statement (LEIS) that determined that egg harvest could occur within the park without impacting gull populations or other park resources. Based on these findings, Congress passed legislation in 2014 authorizing harvest of glaucous-winged gull eggs in Glacier Bay National Park (Lewis and Moss 2015).

NPS/C. Behnke

Joining Forces: Traditional Knowledge and Science

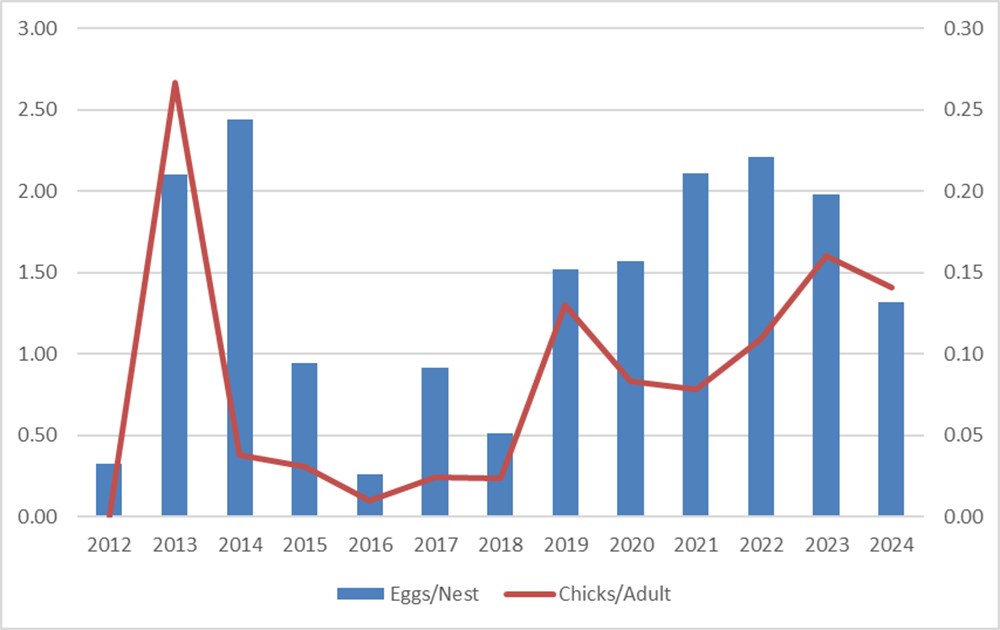

Glaucous-winged gulls are long-lived birds with high site fidelity that nest on grass or rocks on islands or in cliffs with few land predators in Glacier Bay (Hunn et al. 2002, Lewis et al. 2017). These gulls generally lay 3 eggs/clutch with the ability to replace lost eggs and re-lay entire clutches if lost to tidal inundation, predation, or harvest. Gulls begin incubating after the 3rd egg is laid, at which point eggs begin to develop and hatch after 27 days. If eggs are lost or taken from 1- or 2-egg nests, gulls keep laying within a day or two until their clutch is complete. If eggs are lost or taken from a 3-egg nest it may take up to 2 weeks for the gulls to begin laying again (Zador et al. 2006).

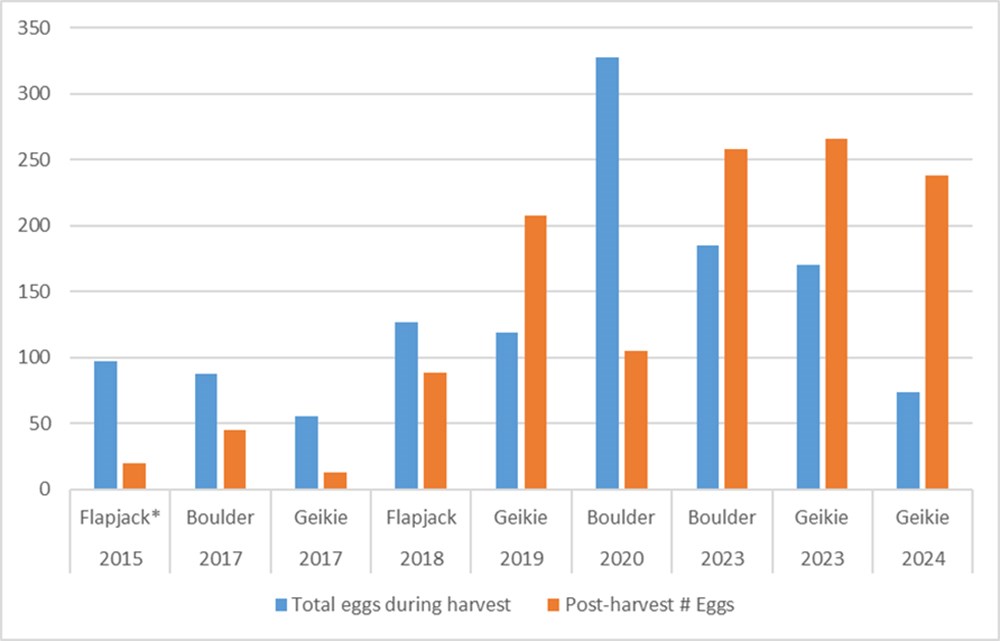

*Egg harvest occurred at only half of the colony at Flapjack in 2015.

Note that eggs were also harvested on Boulder in 2024, but replacement eggs were not counted so not included here.

What We Have Learned

Gull eggs are still treasured by Tribal members. Younger generations have not had access to them and may need more opportunity to acquire a taste. Egg harvest did not cause a decrease in egg size in 2015. There are fewer accessible gull colonies now than in the past, largely due to plant succession. Some colonies are increasing in size, some decreasing. Harvested eggs are sometimes developed, especially from 3-egg nests. Data on egg development of harvested eggs can be difficult to obtain as eggs are distributed to Elders throughout the community and taste for developed eggs varies. Harvesting eggs only from 1- and 2-egg nests allows for early and effective re-laying of eggs by gulls and for repeated harvest at the same location year after year with no apparent negative impacts to gulls. Glaucous-winged gull monitoring since 2012 has led to a large amount of data on yearly seabird nesting distribution, abundance, and productivity.Challenges

One of the biggest challenges of the gull egg harvest and monitoring is limited access to study sites due to marine mammals and weather conditions. Steller’s sea lions, including the threatened western distinct population segment, are increasing on at least one glaucous-winged gull colony and limit access to landing beaches. Harbor seals also regularly haul out near some colonies. The limited number of harvest locations is a challenge as is anticipating the timing of onset of laying from which to plan the egg harvest. Strong winds and high seas can prevent access to the colonies in May-June and cold rain can inhibit egg harvest and nest monitoring due to the potential for eggs to chill and die when incubating adults are disturbed from the nests. Another challenge in assessing gull productivity is that researchers can only conduct nest/egg counts until chicks are mobile, after which time chicks may flee into other gulls’ territories and be killed. Lastly, the gull monitoring project has generated a large amount of data that has led to challenges in data management over the years.

NPS/Tania Lewis

Successes

Since 2015, 982 eggs have been distributed to Tribal members with a focus on Elders. Over 20 Native gull egg harvesters have had an opportunity to practice the traditional activity of harvesting eggs for their community as well as collect data during gull egg harvest. Eight students and entry-level biologists have gained experience in seabird monitoring to inform a traditional gull egg harvest. Tribal and NPS cooperation on gull egg harvests has become a model of Tribal-Federal co-management; this partnership is recognized by the Department of the Interior as one of four successful co-management programs in parks. Importantly, gull egg harvest and monitoring has generated a large amount of baseline data on seabird nesting that can be used to assess yearly breeding success, colony abundance and distribution, indices of marine ecosystem health, and to inform restrictions to recreation visitors protect nesting seabirds. Staff from the Tribe and the park continue to learn from each other in an iterative process that has led to increased awareness and respect, as well as harvest and monitoring strategies that maximize cultural benefits of egg harvest while minimizing negative impacts to gulls in Glacier Bay.

NPS/Mary Beth Moss

Gunalchéesh and Thank You!

- Elders of Hoonah who maintained and fought for the right to continue this tradition

- Park leadership who supported this program

- Hoonah Indian Association harvesters: Lucas Beck, Christopher Behnke, Todd Bruno, Cheryl Cook, David Culp, Sofia Elizarraras, Julie Hower, Jim Lesh, Katja Mocnik, Justin Smith, Ashley Stanek, Elisa Weiss, Kiana Young, and Stephani Zador

- Gulls of Glacier Bay

References

Been, F. 1940.Notes taken in the field during inspection of Admiralty Island, Sitka National Monument and Glacier Bay National Monument, July 8 to August 17, 1940 (in the company of Victor Cahalane, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service). Typescript of daily log. McKinley Park, Alaska.

Cammerer, A. B., 1939.

Superintendent. Correspondence dated December 1,1939, NA, RG 79, Central Classified Files, box 2228, file 208.06 Part I.

Dauenhauer, N. and R. Dauenhauer. 1987.

Haa Shuka: Our Ancestors. University of Washington Press, Seattle and London. 496 pp.

Hunn, E. S., D. R. Johnson, P. N. Russell, and T. F. Thornton. 2002.

A study of traditional use of birds’ eggs by the Huna Tlingit. Techn. Rep. NPS/CCSOUW/NRTR-2002-02. Pacific Northwest Coop. Ecosystem Studies Unit, Seattle.

Goldschmidt, W. R. and T. H. Haas. 1998.

Haa Aani, Our Land. Tlingit and Haida land rights and use. Univ. Washington Press, Seattle.

Goetzmann, W. H. and K. Sloan. 1982.

Looking far north: the Harriman Expedition to Alaska, 1899. Princeton Univ. Press, Princeton, NJ.

Lewis, T. M. and M. B. Moss. 2015.

Glaucous-winged gull monitoring and egg harvest in Glacier Bay, Alaska. Alaska Park Science 14(2):34-39.

Lewis, T. M., C. Behnke, and M. B. Moss. 2017.

Glaucous-winged gull Larus glaucenscens monitoring in preparation for resuming native gull egg harvest in Glacier Bay National Park. Marine Ornithology 174: 165-174.

Milner, A. M., A. L. Robertson, L. E. Brown, S. H. Sonderland, M. McDermott, A. J. Veal. 2011.

Evolution of a stream ecosystem in recently deglaciated terrain. Ecology 92(10): 1924-35.

Schroeder, R. F. 1995.

Historic and contemporary Tlingit use of Glacier Bay. Pages 278-293 in D. Engstrom, ed. Proceedings of the 3rd Glacier Bay Science Symposium, Natl. Park Serv., Anchorage, AK.

Trager, E. A. 1939.

Glacier Bay expedition, 1939. File report, NAPSR RG79, Western Region, central classified files, Box 293.

Zador, S. G., J. F. Piatt, and A. E. Punt. 2006.

Balancing predation and egg harvest in a colonial seabird: a simulation model. Ecological Modeling 195: 318-326.