Last updated: May 12, 2025

Article

The Ecology of Visitation

Investigating the rise of bear-viewing in two remote Alaska parks

Elias Christian, Postgraduate Student, University of East Anglia, Norwich, United Kingdom

NPS/Kevyn Jalone

The remote nature of these parks, while appealing to some visitors, is challenging for researchers. People go to Alaska’s wilderness expressly seeking solitude and frequently complete trips without interacting with any National Park Service (NPS) staff. Alaska parks receive some of the lowest visitation numbers in the National Park System. Yet, as bear viewing interest becomes a dominant activity in southwest Alaska parks, visitor densities are increasing in areas with the highest densities of bears. To prevent overcrowding, reduce adverse bear-human interactions, and to mitigate environmental degradation to bear-viewing locations, parks are charged with incorporating visitor-use data into a strategy for site-specific management action.

At Lake Clark and Katmai there are few reliable single-entry points and little-to-no front-country. Many visitors fly to their selected backcountry locations directly out of Anchorage or Homer. In these remote parks, places with the closest semblance to front-country (Port Alsworth in Lake Clark, Brooks Camp in Katmai), are already located deep within respective park boundaries, off highway systems, and without entrance kiosks and staff resources with consistent methods of counting incoming visitors. These locations are in themselves destinations, not entrances. In this context, baseline establishment of visitor norms, expectations, and experiences is more infrastructurally difficult.

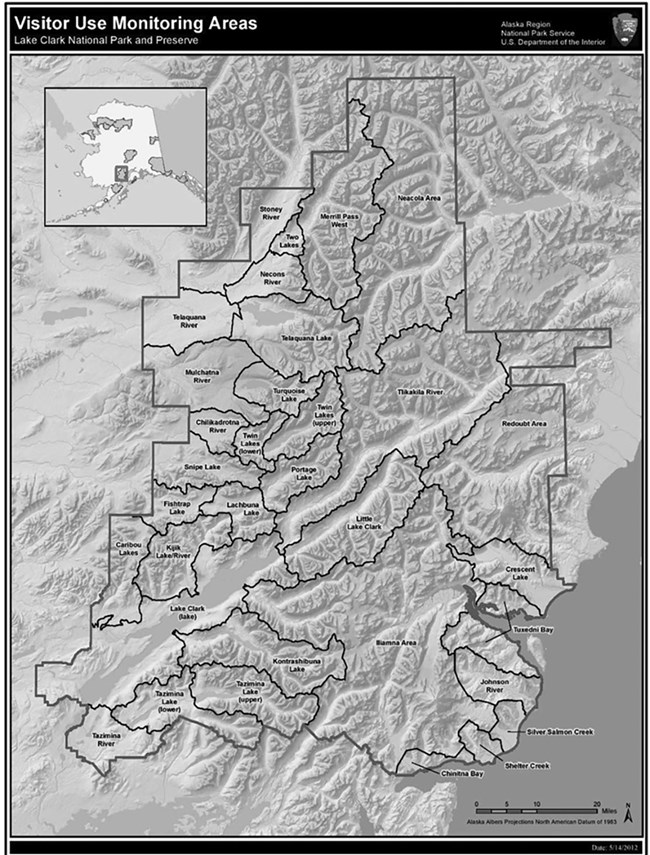

Monitoring visitor use in remote areas is expensive in terms of both access and staffing. The most obvious method for improving visitor-use knowledge—stationing staff at all high-use locations—is far costlier in large, remote parks compared to more accessible parks in other NPS regions. Estimating visitor-use numbers in Lake Clark and Katmai, for example, is primarily limited to the annual reports submitted by commercial use authorization (CUA) permit holders. CUA permit holders are businesses (air taxis, lodges, outfitters, and others) that operate within national parks and are required to submit reports to the NPS to track visitor use and ensure compliance with park regulations. Their reports provide information on trip date, number of visitors transported or guided, areas accessed (Figure 1), and primary activity type. The reports are then aggregated by the parks for a quantitative understanding of visitor use.

CUA reports provide vital information to parks, but the method is a simple index of visitor use that supplies the quantitative elements of park use, like amount and type. It does not provide substantive information about the quality of visitor experience. This information is vital to understanding to visitor experience in parks and how park resources should be managed as bear viewing activities increase. We do not have reliable and regular methods for identifying how close visitors are getting to bears, what level of risk they’re taking or education they’re receiving, how many groups are viewing bears at once, or other elements of their experience and the environmental conditions on site.

As visitor presence in these areas increases, so does the need to manage for visitor satisfaction, providing visitor safety education, and ensuring bear well-being. From 2017 to 2021, a series of visitor-use studies were conducted in Lake Clark and Katmai by teams at the Clemson University Park Solutions Lab and the Kansas State University Applied Park Science Lab. Their research addressed visitor expectations amid increases in bear viewing and the development of methods for collecting better data on visitors in remote areas. Identifying how visitors perceive and evaluate environmental quality is critical to “[anticipating] public responses to the possibility of changing conditions” (Nettles et al. 2021: 18). The study sought to answer the following questions from a few different speculative approaches: How do we ensure that the bears are not detrimentally impacted by increased visitor attention? How do we ensure that the visitors’ experience is not lessened by overcrowding and degraded environmental conditions?

Visitor Use and Satisfaction at Lake Clark National Park and Preserve

Using visitor questionnaires, the first phase of the project identified a set of important indicators and associated thresholds when it came to visitor preferences for conditions during popular park activities—that is, a template for what visitors expect when they come to remote Alaska parks.These indicators and thresholds provide a quantifiable means to analyze the subjective, preferential aspects of park use and visitor experience. Indicators and thresholds are terms foundational to normative theory, an approach to social research postulating that visitors have shared beliefs about aspects important to their experience (Nettles et al. 2020). The indicators establish the variables of experience (as visitors perceive them) while the thresholds provide minimum acceptable conditions that determine a “negative” or “positive” experience. The indicator represents visitor expectation and the threshold represents a preference. The second phase of this project consisted of a second set of questionnaires assessing experienced conditions according to these norm-based thresholds.

- Indicator: Bear proximity.

Threshold: The chance to view a bear at no closer than 9 yards and no farther than 220 yards. - Indicator: Bears viewed.

Threshold: The chance to view at least one (1) bear per hour and no greater than 17 bears per hour. - Indicator: Minutes of human sound per hour.

Threshold: No more than 23 minutes of anthropogenic sound heard per hour. - Indicator: Vegetation degradation.

Threshold: No more than 48% of the vegetation surrounding angling sites degraded. - Indicator: Groups encountered.

Threshold: No more than 6 other visitor groups encountered per day. - Indicator: Groups within view.

Threshold: No more than 6 other visitor groups within view at one time.

As use grows in intensity, specifically at bear-viewing sites, damage to environmental conditions and disturbance to wildlife affects the quality of experience bear-viewers are coming for, potentially disrupting quality of life for bears and visitor satisfaction thresholds. When conditions in an ecosystem change, cascading effects may occur that park managers must be prepared to address. Research on the bears’ physiological state during times of high visitor density along the Cook Inlet coast is ongoing, as the Lake Clark natural resources team examines stress hormones in bear scat.

The Merging of Visitor Use and Wildlife Research

The Nettles-led research team also investigated the potential use of utilization distributions (UDs) as a means of better understanding commercial visitor use patterns. In wildlife research, utilization distribution is a common analysis technique used among biologists to track animals on both the individual and population level (Nettles et al. 2021). Rather than recording the total use of resources over an entire season and representing visitor use as a percentage, or a count, UDs display the intensity of use across a particular place and time, represented as a 3D model that adjusts according to intensity over time. UD methods help establish where visitor densities are highest in the park and how those densities shift over a season (Nettles et al. 2021).The researchers suggest that these spatiotemporal patterns of visitor use can help managers predict and anticipate crowding and congestion in remote areas, reduce impact on sensitive ecological resources, and help identify staffing and resource allocation for specific places at specific times (Nettles et al. 2021). UDs may be a helpful guide that could provide a more complete picture of visitor use that isn’t captured by raw numbers. If applied to human visitation in parks, as Nettles and others suggest, the method carries an interesting implication about conducting visitor research in parks.

The study authors note that “this merging of both wildlife and social sciences is important, as temporal and spatial distributions of visitor use on public lands continue to be of high interest to both scientists and managers” (Nettles et al. 2021: 3) and “doing future research could not only increase understanding of visitor use but also develop the valuable connections between social and wildlife sciences needed for achieving positive human-wildlife coexistence” (Nettles et al. 2021: 15). While we cannot always have reliable data on where visitors are and what they’re doing there, our understanding of where wildlife is at any given place and time is similar. Since the majority of park visitors, whose primary trip objective is to watch wildlife in its natural habitat, are following wildlife, utilization distribution in conjunction with ongoing methods of visitor data collection may be useful to determine where to focus staffing efforts.

This merging of social research with wildlife research in park science involves interpretation and education. It necessitates an informed public that respects and understands wildlife behavior and the impact human activity has on wildlife and protected areas. To mitigate impact, we have a responsibility to moderate behavior. The research suggests that the park’s interpretive efforts focus on promoting a culture of respect and self-awareness among visitors so that they conduct themselves as non-disruptively as any other wildlife population in the ecosystem. From a researcher’s perspective, the study on utilization distribution suggests that gathering time- and location-specific visitor-use data and allocating park resources accordingly may help us to understand visitor activity in these high-use areas.

The recurring (and expanding) presence of visitors in specific wilderness locations is functionally introducing a higher quantum of human activity into an existing ecological landscape, even if an individual visitor is only a short-term or one-time observer. Research into visitor use and the ecology of visitation must reflect visitor presence as a semi-permanent environmental factor. Visitors are not incidental to these high-intensity sites; projections suggest that use will only continue to grow. (Ehrenpreis and Kao 2021).

NPS/Kara Lewandowski

Emotions, Bears, and Broadening Dimensions of Park Use

Addressing how parks can ensure that visitors are interacting with wildlife in an educated and informed way, the researchers looked at the behavioral psychology of wildlife viewing. It examined the emotional responses, across a variety of simulated scenarios, that visitors experience in coastal brown bear interactions. Implementing video simulations and self-assessment questionnaires for a representative sample of the public, the study asked participants to rate the intensity of their emotional responses and then the likelihood of performing several actions on a scale of perceived appropriateness. CUA operators do not have a standardized bear-viewing education program and visitors who come to parks for bear viewing come with diverse backgrounds and levels of preparedness. The study indicates that sometimes what visitors are supposed to do, and even directly instructed to do, conflicts with how they actually behave in reactions to encounters with “hostile” bears, when the visitor perceives hostility in the interaction. (Nettles et al. 2020).Respondents were generally aware of appropriate behavior, but the emotional impact of wildlife interactions heightened by fear had an adverse effect on the ability to make clear choices. This study highlights the gulf between cognition and emotion in bear-viewing visitors; extreme emotion may decrease the impact of safety education on human behavior. The scenario “subadult bear in a meadow” produced the highest degree of attentiveness and the scenario “sow and cubs in a meadow” produced the highest levels of hostility and fear—two negative emotional presets used by the study. While these are both appropriate responses to these scenarios, they also increase the potential for emotion to affect decision making.

The higher the perception of risk, the more likely an emotional response in the human viewer (Nettles et al. 2020). The authors suggest that “experiential training through photographs, videos, or virtual reality could help park visitors and area residents to imagine such scenarios and practice behaving appropriately” (Nettles et al. 2020: 18). Closing the gap between cognitive awareness and emotional response presents a goal to park interpretation and education programs when it comes to mitigating adverse bear-human interactions.

However, the concept of visitation itself begins to beg interpretive redefinition. There is already a distinction between park use and park visitation: traditional subsistence lifestyles or commercial enterprises like the CUAs are both forms of park use, where resources must be stewarded properly to ensure the longevity and the sustainability of these uses. But these practices are not visitation, an intrinsically short-term experience for the individual, but one that is collectively and continually expected to increase. An element of the visitation system that has not yet been fully explored is the use of digital media to engage with national park experiences. While new virtual reality (VR) technology develops and the NPS gets increasingly savvy in the digital media world, employing social media as an experiential education tool for connecting audiences to bears arises as a broadening dimension of park use.

In the International Journal of Wilderness, researchers from the Nettles team examined whether social media, specifically geographical data from tagged posts, is a useful tool for gathering visitor-use data by activity type at Lake Clark and Katmai. Does the social media content containing national park geotags represent in-person visitors by location? The study concluded that services like Twitter (X) or Flickr provide limited usefulness in determining reliable data on in-person visitor activity, particularly in remote areas. Most social media users sharing park-related content were not park visitors to a ratio of about 20 to 1. Out of 3,784 users sharing park-related content, only 189 were confirmed to be in-person visitors (Dagan et al. 2020). Ninety-five percent of Twitter (X) posts about the parks were not visitors. Despite this, “high social media attention from non-visitors may be useful for the park in terms of extending the reach of their education or conservation messages” (Dagan et al. 2020: 24) and understanding public perceptions about remote parks, generally. The researchers intriguingly suggest that a new demographic begins to emerge, that of the “digital park visitor.”

While social media may not be effective for statistical analysis, these results support the idea that digital technology is a valuable tool for educational outreach and accessible virtual experiences in parks (through video content, live webcams, and VR tech). In Katmai National Park and Preserve, for instance, bear-viewing livestreams reach more than 10 million viewers, potentially extending the range of low-access, remote parks to connect with people worldwide. Perhaps the virtual visitor becomes a kind of solution to the problem of increased visitation impacting bears by providing a platform for promoting general attitudes of respect around wildlife viewing among both digital and in-person visitors. This type of visitation has little impact on physical sites and bear-human well-being, accessible education and interpretive opportunities. Someone whose boots will never hit the ground in the remote Alaska wilderness is nonetheless given an opportunity to connect with park resources as digital media grows increasingly sophisticated. However, as general online awareness of the park increases, the visibility of park resources will also serve to drive increased visitation.

The increasing popularity of wildlife tourism in protected areas highlights the need to minimize impacts on wildlife and their habitat. With visitation climbing steadily in parks and protected areas in recent years, the complex nature of human-wildlife interactions suggests an interdisciplinary approach, proactively incorporating both social and wildlife sciences into an ecology of visitation. By improving our understanding of the intersection of social science, wildlife research, and educational outreach, the National Park Service may continue to strive for positive human-wildlife coexistence in protected areas and ensure that our impact on the environment is both minimal and sustainable for generations to come.

References

Brownlee, M. T. J, R. L. Sharp, J. M. Nettles, D. Dagan, and S. Jackson. 2020.Evaluation of the Bear Viewing Experience and Associated Thresholds at Katmai National Park and Preserve and Lake Clark National Park and Preserve. Park Solutions Lab (Clemson University), Applied Park Science Lab (Kansas State University).

Nettles, J. M., M. T. J. Brownlee, J. C. Hallo, D. S. Jachowsk and R. L. Sharp, R. 2020.

Integrating emotional affect into bear viewing management and safety. Ecology and Society 26(2): 19.

Nettles, J. M., M. T. J. Brownlee, R. L. Sharp and R. I. Verbos. 2021.

The utilization distribution: wildlife research methods as a tool for understanding visitor use in remote parks and protected areas. Human Dimensions of Wildlife 27(2): 151-163.

Dagan, D. T., R. L. Sharp, M. T. J. Brownlee, and E. J. Wilkin. 2020.

Social Media Data in Remote and Low-use Backcountry Areas: Applications and Limitations. International Journal of Wilderness 26(1).

Ehrenpreis, V. and M. Kao. 2021.

Commercial Operations at Lake Clark National Park: Market Analysis and Management Options for Bear-Viewing. National Park Service Business Plan Internship Consultants.