Last updated: June 4, 2025

Article

A Data-driven Approach to Transportation Planning in Denali

- William Clark, Physical Scientist, Denali National Park and Preserve, National Park Service

- Dave Schirokauer, Science and Resources Team Lead, Denali National Park and Preserve, National Park Service

NPS/Claire Abendroth

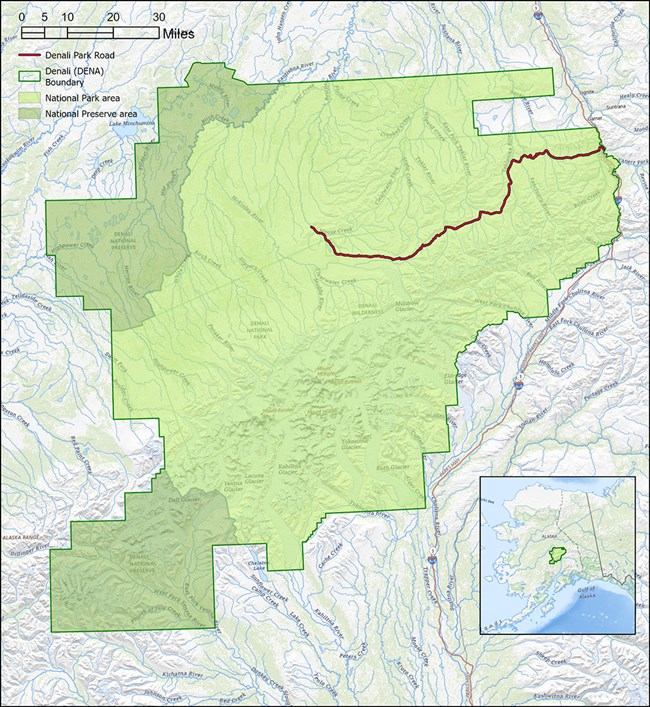

National Boundaries Dataset, 3DEP Elevation Program, Geographic Names Information System, National Hydrography Dataset, National Land Cover Database, National Structures Dataset, and National Transportation Dataset; USGS Global Ecosystems; February 2025.

While no major infrastructure improvements have been made in the more than 50 years since the Parks Highway was completed, Denali tourism demand has continued to increase in step with Alaska tourism broadly. In 2006, park managers initiated a comprehensive study to identify the quantity of traffic that could be accommodated on the park road while protecting park resources and maintaining high-quality visitor experiences–the Organic Act in action. The study has three focus areas: (1) factors important to visitor experience; (2) traffic effects on large mammal behavior; and (3) logistic constraints to park road traffic patterns. Collectively, these studies were synthesized into the Denali Park Road Final Vehicle Management Plan and Environmental Impact Statement (VMP; NPS 2012). The VMP was first implemented in 2013 and is intended to guide vehicle traffic management during the summer season in Denali for the next 20-30 years. It uses an adaptive management approach that includes annual monitoring of desired resource condition indicators. Since 2013, Denali has collected over 70,000 data points of 66 metrics related to 6 indicators of resource conditions, traffic conditions, and visitor experience.

NPS/Tim Rains

Wildlife Viewing

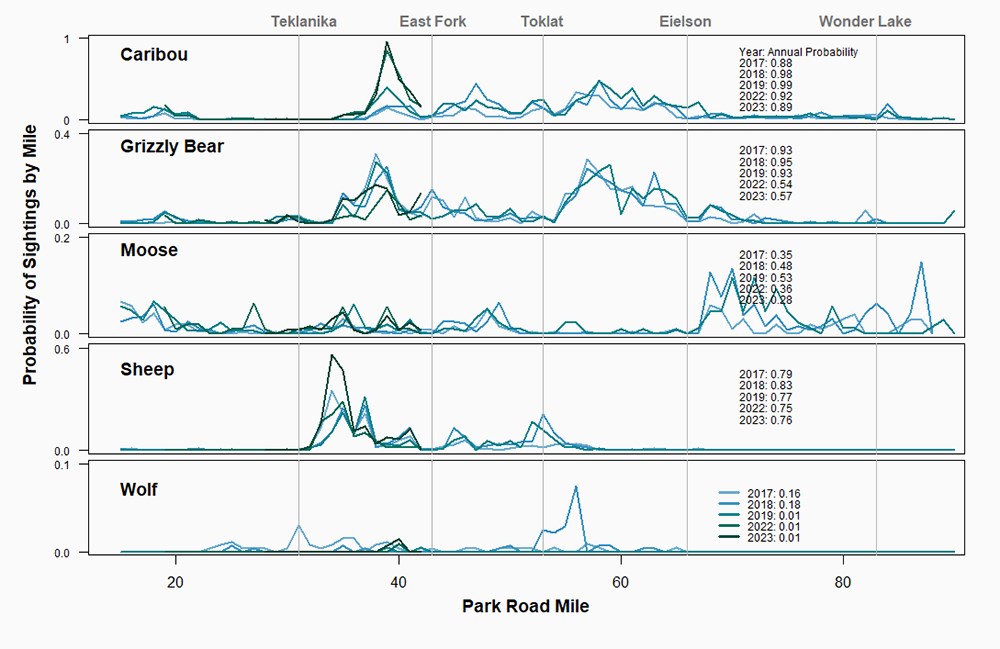

Wildlife viewing may be the core challenge of Denali’s promise to its enabling legislation and the Organic Act and is the principal reason summer visitors come to Denali (Fix et al. 2013). Wildlife can be seen frequently from the bus, but buses can disturb or endanger wildlife. Maintaining the best-possible viewing conditions from both a visitor and wildlife perspective is critical. Under the best conditions, wildlife viewing events are enjoyed by just a few vehicles at a time: The bus slows to a stop and children are hushed as families are awestruck by a caribou’s amber-flecked, brown eyes; the crenulations of a Dall sheep’s thick, curling horns. With engines off, and listening closely, riders can often hear the soft pop of blueberries being pulled from their stems by a grizzly bear readying for an always-nearby winter. These are the indelible images fixed to the spirit of Denali visitors.To protect opportunities for such encounters, the VMP established desired conditions for the number of vehicles present at wildlife viewing stops. We have collected over 24,000 observations at wildlife viewing events since 2013. Prior to the pandemic, the probability of seeing caribou, Dall sheep, grizzly bear, and moose was greater than their 10-year average (Figure 2, last 5 non-COVID years shown). In fact, caribou and moose were at recorded high probabilities and the probability for sighting grizzly bears tied for second highest on record. Wolves have been less frequently observed in the last 5 years.

NPS/Mary Lewandowski

Interestingly, the percentage of time that bears were observed close to (less than 36 feet [11 m]) or on the eastern half of the park road has increased slightly since 2020. We will collect more years of data to investigate if the compressed road access could be a factor.

The landslide on the park road has presented an unprecedented opportunity to conduct a before-and-after study of traffic on a road in a world-renowned wildlife landscape. To further describe grizzly bear behavior in the presence and absence of park road traffic, Denali will examine the locations and activities of GPS-collared bears (about 12 individuals) on the nearly vehicle-absent (using vehicle-based observations) west side of the road compared to bears on the east side of the road exposed to more traffic. The study launched in 2022 and will continue for 2 years after the landslide-spanning bridge project is completed.

Vehicle Spacing

Beyond wildlife viewing, protecting the free movement of wildlife is also a management priority. Wildlife collar data from the 2006 study data suggested that vehicle spacing (gaps in traffic) is particularly important for Dall sheep. Dall sheep frequently navigate from the Alaska Range south of the road to the mountains north of the road (for reasons including seeking lambing grounds, browse, and protection from predation) and their movements became hurried and erratic in the presence of higher traffic volumes (Phillips et al. 2010). In fact, the movement speed of Dall sheep increased 5-fold when crossing the road compared to their other activities. Considering some sheep crossed the road over 50 times over the 4-month study, hurried movement to avoid road-based interactions has a real caloric cost that may reduce recruitment. To protect opportunities for wildlife to move freely from one side of the road to the other, Denali established a desired condition that every hour have a minimum of one 10-minute period when traffic does not pass, known as “sheep gaps.” This has been the most difficult VMP standard to meet. The VMP establishes a goal of meeting vehicle spacing standards 90% of the time (e.g., 90 of 100 days). Denali has met the standard 60% of the time.When desired conditions are unmet, the VMP prioritizes adopting the least restrictive management tactic before escalating. Following several years of adapting vehicle schedules with mixed success, mandatory stopping at sheep gap sites was implemented in 2022. When a vehicle arrives at a critical wildlife zone identified in the VMP within the first 10 minutes of the hour, that vehicle is expected to stop until 10 minutes past the hour. The strategy appears to have been effective. Both sites (the only two currently open to vehicle traffic) met the VMP standard in both 2022 and 2023, marking only the first and second time that one of these sites met management goals since 2015. Moreover, the data show that 1 of the 2 sites would have failed to meet the desired condition had the mandatory stopping not been in place in 2022.

While the VMP may have been written to mean that traffic volumes should be at a level such that random 10-minute breaks in traffic occur every hour, that condition has been rare since 2013. Though not random, mandatory breaks in traffic are an effective and valuable management adaptation and emblematic of the creative solutions required from land managers as pressures on park facilities increase.

NPS/Jacob Frank

Closing Thoughts

At its core, the VMP is a monitoring program born of an opportunity to address carrying capacity. The concept is simple: Within the park road corridor, at some level of traffic condition (e.g., quantity, frequency, or type), there will be measurable negative effects on natural and cultural resources and visitor experience. Many of those negative effects can be curbed by requiring an ATS, such as a busing system.ATSs are not a panacea because they can also have negative effects to the environmental, social, or economic qualities of a park (Spernbauer et al. 2022). Some of the environmental and social benefits are clear and calculable (e.g., carbon footprint), while others are harder to quantify. For example, ATSs are expensive to operate, rarely free, and not possible for all capabilities of visitor. It is important to ask, who are we excluding from entry due to access or price barriers?, which likely requires site-specific study. Denali is not immune to these challenges, and they should be considered.

Even so, Denali has observed successes. In 2019–the last year with access comparable to historic data–about 13,477 vehicles transited the park road, which is only 800 more vehicles than in 1984 (about 12,661 vehicles), and simultaneously increased park road access by 31% (about additional 68,000 visitors). Not many places in the world could claim that, let alone a high-profile North American national park. Many parks are challenged by capacity-related issues like crowds and traffic congestion, which threaten natural and cultural resources and the quality of visitor experiences. For managers looking to use data-driven means to maintain visitor experience and resource protection, the VMP may be a helpful model. Perhaps an ATS could benefit your favorite park.

References

Clark, W. C. 2023.

Current conditions of standards from the Denali Park Road Vehicle Management Plan: 2022 summary report. Denali National Park and Preserve. National Park Service, Fort Collins, CO.

Fix, P. J., A. Ackerman, and G. Fay. 2013.

2011 Denali National Park and Preserve visitor characteristics. Natural Resource Technical Report. NPS/AKR/NRTR–2013/669. National Park Service, Fort Collins, CO.

Keller, R. 2019.

Backcountry Visitor Experience Survey Report Briefs. National Park Service, Fort Collins, CO.

National Park Service (NPS). 2022.

NPS National Transit Inventory and Performance Report, 2022. Available at: https://home.nps.gov/subjects/transportation/upload/NPS-Transit-Inventory_2022-508.pdf (accessed 9 May 2025)

National Park Service (NPS). 2012.

Final Vehicle Management Plan and Environmental Impact Statement. NPS 184/107317 July 2012. Available at: https://www.nps.gov/dena/learn/management/roadvehmgteis.htm (accessed 9 May 2025)

Phillips, L. M., R. Mace, T. Meier. 2010.

Assessing impacts of traffic on large mammals in Denali National Park and Preserve. Park Science 27(2): 60-65. National Park Service, Denver, CO.

Spernbauer, B., C. Monz, and J. W. Smith. 2022.

The effects and trade-offs of alternative transportation systems in U.S. National Park Service units: An integrative review. Journal of Environmental Management 315: 115138.