Last updated: July 21, 2025

Article

Changing Visitation Patterns Present Challenges and Opportunities for Alaska National Parks

- H. Sharon Kim, Outdoor Recreation Planner, National Park Service Alaska Regional Office (formerly)

- Sean Eagan, Interdisciplinary Resources Program Manager, Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve

- Dave Schirokauer, Science and Resources Team Leader, Denali National Park and Preserve

NPS/SEAN TEVEBAUGH

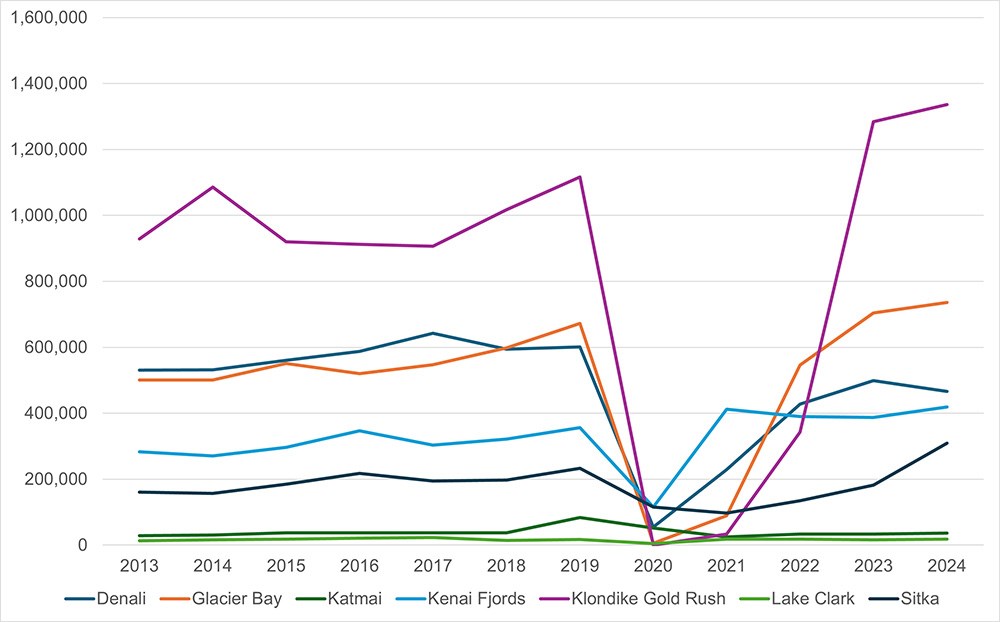

Data are from NPS STATS (2025). Glacier Bay, Katmai, Kenai Fjords, Klondike Gold Rush, Lake Clark, and Sitka parks have increased from 2013-2024, and Denali has decreased.

Shifting Visitor Seasons from Warmer Temperatures

High latitudes are warming more quickly than the global average; for example, the Arctic is warming nearly four times faster (Rantanen et al. 2022). Decreases in sea ice extent and the warmest summer surface air temperatures on record have been documented recently (NOAA 2023). Related effects include earlier green-up dates (Fresco et al. 2021), and earlier snowmelt and later freeze-up determined from stream flow discharges (Blaskey et al. 2023). By extension the warming climate has become a key park management consideration because these changes impact visitation patterns and the length of the visitor season.

For example, in many parks in northern and Interior Alaska, the standard date for the start of public-related summer operations has been Memorial Day weekend, while the end of the season has been more variable, ranging from Labor Day through mid-September. A study looking at 3 parks across a latitudinal gradient (Gates of the Arctic, Denali, and Katmai national parks and preserves) determined that temperatures for the shoulder season months of May and September are becoming more similar to temperatures currently in June through August, likely leading to a longer peak visitor-use season (Albano et al. 2013). In Kenai Fjords National Park, access to Exit Glacier, a key visitor attraction, is limited by snow depth in the spring due to the inability to open the road. As the climate warms and winter rain replaces snow, conditions may allow for earlier road access (Walsh et al. 2023, Sousanes et al. 2023). When roads open earlier, park visitors often expect facilities such as visitor centers to also be open earlier. This happened in 2014-2016 when Seward experienced low-snow winters and the state-owned road to Kenai Fjords National Park was opened in mid-April, putting social pressure on the park to open the park road and visitor facilities in late April instead of mid-May. While trails and restrooms were opened earlier in those years, the visitor center was not opened until Memorial Day weekend because it requires extensive staffing. (In contrast, in 2024, the road opened in mid-May, which shows that low-snowfall winters are not a certainty and prevents the park from counting on a consistent April opening for staffing decisions.)

With extended visitor seasons for parks, popular visitor activities such as wildlife viewing may also start earlier in the year and possibly continue later into fall. For example, bears, which are popular viewing experiences for visitors, are emerging from their dens earlier and hibernating later as temperatures warm (Johnson et al. 2018, Kurth et al. 2024). Their movements and distributions are also changing as the availability of fish, berries, and other food sources also shift (Taylor 2008, Pigeon et al. 2016, Deacy et al. 2017). These trends increase the opportunity for human-bear interactions, a recurring safety and management issue for many parks (Kurth et al. 2024).

With extended visitor seasons for parks, popular visitor activities such as wildlife viewing may also start earlier in the year and possibly continue later into fall. For example, bears, which are popular viewing experiences for visitors, are emerging from their dens earlier and hibernating later as temperatures warm (Johnson et al. 2018, Kurth et al. 2024). Their movements and distributions are also changing as the availability of fish, berries, and other food sources also shift (Taylor 2008, Pigeon et al. 2016, Deacy et al. 2017). These trends increase the opportunity for human-bear interactions, a recurring safety and management issue for many parks (Kurth et al. 2024).

Expansion of Cruise Ship Docks in Alaska

Another reason for changing visitation to Alaska’s national parks is due to the expansion of the port infrastructure available for large cruise ships that bring a disproportionate number of tourists to Alaska. Favorable global economic trends, including a growing middle class with increased spending power (Brookings Institution 2021), also result in expanded cruise ship operations. In 2023, 1,650,000 cruise ship visitors were brought to Alaska compared to 951,000 visitors in 2006, an increase of over 70% (CLIA 2024). Southeast Alaska parks, such as Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve, are currently seeing the visitor season extend from late April through mid-October, a marked change from 20 years ago when ships were rarely seen before 1 May and never after early September. To that point, in 2013, Glacier Bay had 575 cruise ship visitors in April; in 2023, there were 8,389 cruise ship passengers in April and 43,922 visitors in October (NPS 2025).

NPS

In Sitka, a private cruise ship docking terminal was constructed about 5 miles from downtown in 2011 and in 2022, this terminal was expanded to accommodate 2 cruise ships simultaneously, including a large ship capable of carrying 4,900 guests (KTOO 2021). In 2023, more than 500,000 cruise ship passengers visited Sitka compared to the previous record of 289,000 in 2008 (Wrangell Sentinel 2023). Sitka National Historical Park, located 1 mile east of the downtown area, is currently in the process of a visitor use management and transportation plan to address this increase in visitors.

The City of Nome is expected to have the very first U.S. deep-water port in the Arctic with expected completion by 2027 (USACE 2022). This is expected to increase cruise ship traffic to Nome including passenger excursions to the nearby Bering Land Bridge National Preserve.

Even parks that do not have a gateway community near a port are being affected by the increase in cruise ship tourism. As of 2024, parks such as Lake Clark National Park and Preserve are seeing cruise ship visitors through packaged excursion trips (Lake Clark National Park staff, pers. comm., August 8, 2024). This has contributed to the increased number of visitors coming to coastal bear-viewing sites in mid-May, starting the visitor season around 2 weeks earlier and with larger groups.

Other Travel Trends

Another climate related social factor that may be influencing changes to park visitation in Alaska has been termed coolcation, defined as people seeking vacation destinations with cooler summer temperatures (Condé Nast Traveler 2023). The record summer heatwaves that have been affecting the lower-48 states and Europe are expected to continue and possibly increase in frequency (Copernicus 2024, NASA 2024). 2024 has been identified as the warmest year on record with the hottest August documented in the 175-year record (NOAA 2025). The relatively cooler summer temperatures coupled with the long summer daylight make Alaska more attractive for a coolcation.Another recent travel trend that is affecting Alaska is referred to as last-chance tourism (Lemelin and Whipp 2019) where people travel to destinations to see attractions that may soon vanish due to climate change or development (Forbes 2018). Alaska national parks support an extensive network of glaciers which are one of the primary destinations for those acting on, and engaging in, last chance discourse (commentary about their experience; Abrahams et al. 2022). For example, the Exit Glacier at Kenai Fjords National Park has been retreating rapidly since 2004 (the glacier terminus has retreated over a half mile; NPS 2024).

NPS (1992), NPS/S. McKnight (2010), NPS/J. Rodrigues (2024)

Alaska International Airlines Systems 2024

Management Challenges and Opportunities

While cruise ships and airlines are poised to accommodate more visitors in the shoulder seasons, the National Park Service is increasingly challenged to address the potential increase in overall visitor numbers and length of season. Managing visitor experiences is another challenge for park managers and includes addressing visitor expectations in a rapidly changing environment. Two frameworks may be particularly helpful when considering future management actions for parks: scenario planning and the Resist-Accept-Direct framework.Scenario planning is a structured way of recognizing that the future is not always clear and provides a way to think through actions related to different possible futures (Schoemaker 1995). By exploring multiple possible futures instead of focusing on a single future, scenario planning can be particularly useful in conditions of high uncertainty (NPS 2013). This process is also a way to identify actions that can work across many of the various scenarios, leading to a more robust set of solutions. For example, the southwest Alaska parks used climate change scenarios to understand implications for riverine and coastal systems (Winfree et al. 2014). When considering park management actions related to visitors, it is important to consider how visitation may change in the future especially related to seasonality and overall number, as well as understanding how visitor experience may change.

In light of the uncertain rate of Exit Glacier retreat and future visitation numbers, Kenai Fjords National Park used scenario planning to identify robust management actions across various future scenarios (Kim et al. 2020). As mentioned earlier, visitor experience at Kenai Fjords National Park has greatly changed over the last 20 years for Exit Glacier, a key location in the park’s frontcountry area accessible by road vehicle. Back in 2004, Kenai Fjords National Park released the Exit Glacier Area Plan, An Environmental Assessment and General Management Plan Amendment (NPS 2004), which focused on Exit Glacier as the primary park visitor attraction accessible by road. The purpose of the 2004 plan stated that “Exit Glacier provides visitors with a rare opportunity to easily approach a glacier on foot” and that visitors “can drive within one-half mile of the glacier terminus and walk a relatively easy path to its towering face of ice.” In 2004, Exit Glacier was considered to be fairly stationary as the terminus (bottom edge) had receded only 184 feet (56 m) from 1974-2004 (Kurtz and Baker 2016). However, from 2003 to 2023, the terminus receded a half mile (2,640 feet [804 m]; NPS 2024) and the glacier is no longer accessible to most visitors. Today, some visitors still come to Kenai Fjords National Park expecting to stand next to a glacier, but the glacier has now retreated substantially up a steep slope and can no longer be accessed by the lower trails. Because of this major retreat of Exit Glacier, scenario planning was used to come up with robust solutions across different scenarios of the rate of Exit Glacier retreat and various visitation levels. These robust solutions were incorporated into the 2024 Kenai Fjords Frontcountry Management Plan Environmental Assessment (NPS 2024), focusing more on the frontcountry area as a whole with the intent to help shift visitor focus away from Exit Glacier. Park visitor programs have shifted beyond Exit Glacier to broaden people’s understanding of glacial processes, the Harding Icefield, and the fjords with over 500 miles of coastline.

Another management tool for making decisions for park areas undergoing rapid change is the Resist-Accept-Direct (RAD) framework (Schuurman et al. 2020). This framework has been applied to ecosystems undergoing rapid, irreversible ecological change. While the NPS has often focused on restoring ecological systems within a historic range of variability, the RAD framework applies when this range shifts and the historic range of variability no longer applies. The RAD framework has park managers consider what makes the most sense: resist the change and try to restore back to the historic conditions, accept the change with little action to manipulate it into something different, or direct the change by actively managing it towards specific new desired conditions.

While the RAD framework focuses on ecological change, this framework can also apply to shifting park visitation. For example, when a new cruise ship dock near a railroad depot is built within Alaska, this may shift the visitation number in a railroad-accessed park much higher than in the past and across an expanded season. New visitor excursions can also cause an influx of visitors where they were not as prevalent before either in location, time period, or both. Depending on the visitor use management actions and related capacity of the park area, these greater numbers may be resisted (e.g., limit access due to resource damage and visitor capacities being exceeded); accepted (e.g., access can be allowed when capacities are not reached and resource impacts are not occurring at unacceptable levels), or directed (e.g., management actions provide for a greater number of visitors in particular areas where resource damage can be minimized).

Overlaying visitor management on a shifting environment due to an extended visitor season and increasing visitation may be challenging, but combining scenario planning with the RAD framework may be particularly helpful for identifying a clearer set of robust options in an uncertain future. Several scenarios may warrant the same RAD framework strategy. Management actions that apply to more than one scenario are considered robust and management actions that cross over all of the scenarios are considered to be the most robust, as Kenai Fjords National Park found when they used the scenario planning as a starting point to determine management actions.

References

Abrahams, Z., G. Hoogendoorn, and J. M. Fitchett. 2022.Glacier tourism and tourist reviews: an experiential engagement with the concept of “Last Chance Tourism.” Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism 22(1): 1-14.

Airport Council International. 2024.

Top 10 Busiest Airports in the World Shift with the Rise of International Air Travel Demand. 14 April 2024. Press release. Available at: https://aci.aero/2024/04/14/top-10-busiest-airports-in-the-world-shift-with-the-rise-of-international-air-travel-demand/ (accessed on May 30, 2024).

Alaska International Airlines Systems. 2024.

Available at: Air Cargo, Alaska International Airport System, Transportation & Public Facilities, State of Alaska (accessed on May 30, 2024).

Albano, C. M., C. L. Angelo, R. L. Strauch, and L. L. Thurman. 2013.

Potential effects of warming climate on visitor use in three Alaskan national parks. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Park Science 30: 36-44.

Anchorage Daily News (ADN). 2022.

A dock project in Seward will bring even bigger cruise ships to Southcentral Alaska. Available at:https://www.adn.com/business-economy/2022/05/30/100-million-dock-project-in-seward-to-bring-even-bigger-cruise-ships-to-southcentral-alaska/ (accessed on August 15, 2024).

Blaskey, D., J. Koch, M. Gooseff, A. Newman, Y. Cheng, J. O’Donnell, and K. Musselman. 2023.

Increasing Alaskan river discharge during the cold season is driven by recent warming. Environmental Research Letters 18: 024042.

Brookings Institution. 2021.

A long-term view of COVID-19’s impact on the rise of the global consumer class. Available at: A long-term view of COVID-19’s impact on the rise of the global consumer class (brookings.edu) (accessed on September 18, 2024).

City of Whittier. 2024.

Head of the Bay Project. Available at: https://www.whittieralaska.gov/bay-project/ (accessed on August 15, 2024).

Condé Nast Traveler. 2023.

The Biggest Travel Trends to Expect in 2024. https://www.cntraveler.com/story/travel-trends-2024 (accessed on July 30, 2024).

Copernicus. 2024.

Copernicus: Summer 2024 – Hottest on record globally and for Europe. Available at: https://climate.copernicus.eu/copernicus-summer-2024-hottest-record-globally-and-europe (accessed September 9, 2024).

Cruise Lines International Association (CLIA). 2024.

History of Cruise Industry in Alaska. Available at: https://akcruise.org/economy/alaska-cruise-history/ (accessed on August 14, 2024).

Deacy, W. W., J. B. Armstrong, W. B. Leacock, C. T. Robbins, D. D. Gustine, E. J. Ward, J. A. Erlenbach, and J. A. Stanford. 2017.

Phenological synchronization disrupts trophic interactions between Kodiak brown bears and salmon. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 114(39): 10432-37.

Forbes. 2018.

Last-Chance Tourism Named Top Travel Trend For 2018. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/alexandratalty/2017/12/28/for-second-year-last-chance-tourism-named-top-travel-trend-for-2018/ (accessed May 12, 2025)

Fresco, N., A. Bennett, P. Bieniek, and C. Rosner. 2021.

Climate change, farming, and gardening in Alaska: Cultivating opportunities. Sustainability 13: 12713.

Johnson, H. E., D. L. Lewis, T. L. Verzuh, C. F. Wallace, R. M. Much, L. K. Willmarth, and S. W. Breck. 2018.

Human development and climate affect hibernation in a large carnivore with implications for human–carnivore conflicts. Journal of Applied Ecology 55(2): 663-672.

Kim, H. S., K. DesErmia, B. Pister, S. Potocky, and E. Veach. 2020.

Scenario Planning Discussions for the Future Frontcountry Management Plan, Kenai Fjords National Park. National Park Service. Available at: https://www.nps.gov/kefj/learn/management/upload/FINAL-Scenario-Report-5-27-2020-508-compliant.pdf (accessed May 12, 2025)

KTOO. 2021.

Private dock projected to double Sitka cruise passengers in 2022. Available at: https://www.ktoo.org/2021/09/08/private-dock-projected-to-double-sitka-cruise-passengers-in-2022/ (accessed on July 31, 2024).

Kurth, K. A., K. C. Malpeli, J. D. Clark, H. E. Johnson, and F. T. van Manen. 2024.

A systematic review of the effects of climate variability and change on black and brown bear ecology and interactions with humans. Biological Conservation 291: 110500.

Kurtz, D. and E. Baker. 2016.

Two hundred years of terminus retreat at Exit Glacier: 1815 to 2015. Natural Resource Report NPS/KEFJ/NRR—2016/1341. National Park Service, Fort Collins, Colorado.

Lemelin, H. and P. Whipp. 2019.

Last chance tourism: A decade in review. pp. 316-322 In D. Timothy (Ed.), Handbook of Globalisation and Tourism. Edward Elgar Publishing, London: United Kingdom.

McDowell Group. 2020.

Alaska Visitor Volume Report Winter 2018-19 and Summer 2019. Prepared for Alaska Travel Industry Association.

McKinley Research Group. 2025.

Alaska Visitor Volume Summer 2025. Prepared for Alaska Travel Industry Association.

McKinley Research Group. 2023.

Ted Stevens Anchorage International Airport Economic Impact Study. Prepared for Anchorage Economic Development Corporation.

National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). 2025.

Temperatures Rising: NASA Confirms 2024 Warmest Year on Record – NASA. Available at: https://www.nasa.gov/news-release/temperatures-rising-nasa-confirms-2024-warmest-year-on-record/ (accessed May 5, 2025)

National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). 2024.

In the Grip of Global Heat. Available at: https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/152995/in-the-grip-of-global-heat (accessed on July 31, 2024).

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). 2025.

Earth had its hottest August in 1,750-year record. Available at: https://www.noaa.gov/news/earth-had-its-hottest-august-in-175-year-record (accessed on May 12, 2025).

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). 2023.

Arctic Report Card: Update for 2023. Available at: https://arctic.noaa.gov/report-card/report-card-2023/ (accessed on April 5, 2024)

National Park Service (NPS). 2025.

STATS – National Reports. Available at: https://irma.nps.gov/Stats/Reports/National (accessed May 12, 2025)

National Park Service (NPS). 2024.

Kenai Fjords National Park Frontcountry Management Plan and Environmental Assessment. Seward, Alaska.

National Park Service (NPS). 2013.

Using Scenarios to Explore Climate Change: A

Handbook for Practitioners. National Park Service Climate Change Response Program. Fort Collins, Colorado.

National Park Service (NPS). 2004.

Exit Glacier Management Plan Environmental Assessment (General Management Plan Amendment).

Pigeon, K. E., G. Stenhouse, and S. D. Côté. 2016.

Drivers of hibernation: Linking food and weather to denning behaviour of grizzly bears. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 70: 1745-1754.

Rantanen, M., A. Karpechko, A. Lipponen, K. Nordling, O. Hyvarinen, K. Ruosteenoja, T. Vihma, and A. Laaksonen. 2022.

The Arctic has warmed nearly four times faster than the globe since 1979. Communications Earth & Environment 3: 168.

Schoemaker, P. J. H. 1995.

Scenario Planning: A Tool for Strategic Thinking. Sloan Management Review. 36(2): 25-40.

Schuurman, G. W., C. Hawkins Hoffman, D. N. Cole, D. J. Lawrence, J. M. Morton, D. R. Magness, A. E. Cravens, S. Covington, R. O’Malley, and N. A. Fisichelli. 2020.

Resist-accept-direct (RAD)—a framework for the 21st-century natural resource manager. Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/CCRP/NRR—2020/ 2213. National Park Service, Fort Collins, Colorado. https://doi.org/10.36967/nrr-2283597

Sousanes, P. J., K. Hill, D. Swanson, J. O’Donnell, P. Kirchner, D. Kurtz, M. Loso, and A. Bliss. 2023.

Crossing the zero-degree threshold. Alaska Park Science 22(1): 6-21.

Taylor, S. G. 2008.

Climate warming causes phenological shift in pink salmon, Oncorhynchus gorbuscha, behavior at Auke Creek, Alaska. Global Change Biology14: 229-23.

The Seward Company. 2024.

Port of Tomorrow. Available at: https://sewardcompany.com/ (accessed April 15, 2024).

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE). 2022.

Port of Nome Modification Project. Community Information Meeting Slides, February 9, 2022. Available at: https://www.poa.usace.army.mil/Portals/34/PortofNomePublicInfoMtg20220207.pdf (accessed July 31, 2024).

Walsh, J. E., S. Bigalke, S. A. McAfee, R. Lader, M. C. Serreze, and T. J. Ballinger. 2023.

NOAA Arctic Report Card 2023: Precipitation. NOAA technical report OAR ARC; 23-04.

Winfree, R., B. Rice, N. Fresco, L. Krutikov, J. Morris, D. Callaway, D. Weeks, J. Mow, and N. Swanton. 2014.

Climate change scenario planning for southwest Alaska parks: Aniakchak National Monument and Preserve, Kenai Fjords National Park, Lake Clark National Park and Preserve, Katmai National Park and Preserve, and Alagnak Wild River. Natural Resource Report NPS/AKSO/NRR—2014/832. National Park Service, Fort Collins, Colorado.

Wrangell Sentinel. 2023.

Sitka on track for record half-million cruise passengers this summer. Available at:

https://www.wrangellsentinel.com/story/2023/09/13/news/sitka-on-track-for-record-half-million-cruise-passengers-this-summer/12309.html (accessed August 21, 2024).

Tags

- bering land bridge national preserve

- denali national park & preserve

- glacier bay national park & preserve

- katmai national park & preserve

- kenai fjords national park

- klondike gold rush national historical park

- lake clark national park & preserve

- sitka national historical park

- alaska

- alaska park science

- aps

- human dimensions

- park visitors

- visitation

- nps tourism