Part of a series of articles titled Reckoning with a Warming Climate.

Article

Communicating Science and Inspiring Hope

Laura Buchheit, Deputy District Ranger, Tongass National Forest, Juneau Ranger District, U.S. Forest Service

Jamie Hart, Interpreter, Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve, National Park Service

Laurie Lamm, Supervisory Park Ranger (Interpretation), Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve, National Park Service

Paul Ollig, Director of Interpretation and Education, Denali National Park and Preserve, National Park Service

NPS/JESSICA WEINBERG MCCLOSKEY

Effective communication about the changing climate is more than informing people about facts, it’s inspiring them to appreciate and care about what the facts represent. Successful park interpreters provoke their audiences to take action and support efforts to respond effectively to the climate changes taking place in parks (Tilden 2008, Beck and Cable 1998). That’s not always an easy task.

A recent study from the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication (Leiserowitz et al. 2022) found that 64% of Americans are somewhat or very worried about climate change, yet 67% of these same individuals admit they “rarely” or “never” discuss it with their friends or family. This points to the important role interpreters, educators, and science communicators have to encourage discourse and inspire people to take action. Interpreting climate change begins by understanding the science, identifying relevant culturally appropriate connections to each audience, and using the best available techniques for people to engage with the science in memorable ways.

Since 2004, the National Park Service has collaborated with National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), and other federal agencies including the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the U.S. Forest Service, in the Earth to Sky Partnership. In this partnership, interpreters, educators, and scientists form a community of practice to learn, share science findings and communication techniques, and develop science-rich interpretive products and programs for use in parks, refuges, and other place-based education sites. Example communication products, archives, and other valuable resources for effective science communication are available on the Earth to Sky website.

At their best, interpretive products are simple and straight-forward. The goal is to let observation and experience inspire appropriate action in response. Earth to Sky helps both communicators and scientists understand when the audience experience is sufficient, and when additional methods of discovery are needed. This article highlights examples that illustrate the process of telling stories of a changing climate while inspiring action and hope in response.

When the story to tell is complex or not obvious, interpreters can use a clear and intentional process to guide their communication efforts (NPS 2016a). The steps to do this include defining the key messages to convey, figuring out who the audiences are to receive them, and customizing the best methods to use so each message is successfully delivered.

A special emphasis upon audience-centered experiences and grounding the products in both science and Indigenous knowledge is also important. Most Alaska parks are subsistence parks with communities that have lived experience of climate change effects on the environment, fish and wildlife, and way of life. Reflection of the communities and culture that are part of the parks and might serve to engage public with direct and tangible understanding of impacts of climate change, inspire them to take action, and instill hope.

Recent models of human cognition and behavior recognize that conclusions audiences draw from their own discussion and shared experiences are much more powerful than those they are told to draw by someone else (Toomey 2023). As with science, interpretation is peer reviewed and evaluated to make sure it can be replicated or improved, as needed. In some cases, when multiple messages and audiences are involved, a formal plan is developed to outline a full communication campaign.

ALASKA COASTAL RAINFOREST CENTER

Defining Key Messages

What are the main concerns park managers need to address? What do they want constituents to care about and do in response? In developing interpretive products, interpreters use science to define the key messages and provide an understanding of the questions being studied. Steeping the audience in science helps reinforce any key messages or questions that need to be remembered. Most of all, grounding the products in science helps communicators explain what success would look like and why the issue is relevant to people.

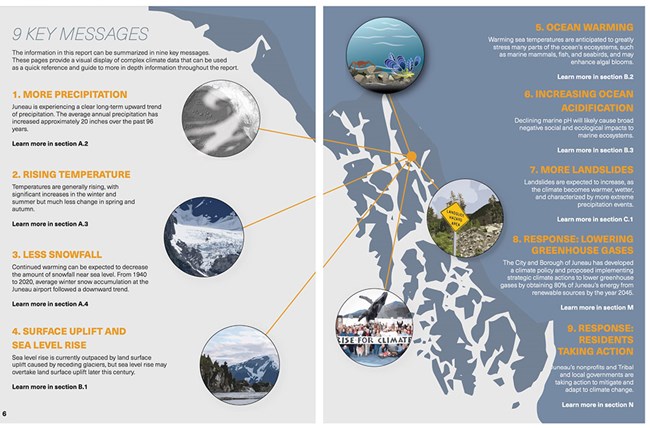

Juneau’s Changing Climate and Community Response

The community of Juneau designed and published Juneau’s Changing Climate and Community Response as a unique way to inform and engage members of the community, decision makers, academics, and non-profits alike (Alaska Coastal Rainforest Center 2022). Using contributions from a variety of scientists and community members, the authors sought to develop key messages and recommended actions that could serve the whole community. The nine key messages are intended for use as a quick reference. Unique for this type of report, these key messages highlight actions by Juneau’s civil society, including local non-profit organizations.

Identifying the Audience and Relevance

Once a key message or theme is defined, the next step in the interpreter’s process is to determine how those messages and themes are most relevant and to whom. For each message, it works best to identify as many groups of potentially interested parties as possible. Although each person may have unique interests and values to consider, there are often groups of people who share similar concerns. To communicate best, it’s important to know what is relevant to each group. This step may address community groups, tour guides and vendors, managers, visitors, students and teachers of various grades, social organizations, commercial organizations, and even scientists themselves. For some groups a written publication may be most effective, while for others, an in-person meeting or event might be best.

Interpreting Climate Change to Cruise Ship Passengers

At Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve, interpreters meet the majority of park visitors on cruise ships. Park programs and products need to be portable and engaging to supplement the experience visitors have while cruising through the park. These products also serve as catalysts for conversation about the park’s significant meanings and issues, including climate change. Rangers use short presentations, a traveling visitor center, and informal roving activities to connect with thousands of diverse passengers. Social science research concluded that a majority of Glacier Bay visitors want to experience wilderness landscapes and often develop a strong sense of connection to Glacier Bay, even after just one visit (Furr et al. 2021). Yet, even though cruise ship passengers are surrounded by wilderness, their elevated shipboard viewpoint keeps them at a distance from the primary features.

Rangers and displays become a vital catalyst for passengers to have a more personal engagement with the resource. The informal setting puts passengers in control of the conversation by letting them choose what to talk about with the rangers. Passengers choose from an array of possible scientific, historical, and indigenous topics, and rangers encourage them to share from their own expertise and experience in a true dialogue of interest. Visitors often acknowledge these personal contacts with rangers as a highlight of their trip, while the desk displays and handouts provide the catalysts for that engagement and connection.

Based on social science and Earth to Sky connections, Glacier Bay interpreters recently revised the traveling desk displays onboard cruise ships to focus on the science of how climate is influencing the park. These new displays facilitate curiosity and encourage visitors to start talking about glaciers and climate change. The enthusiasm coming from their conversations create long-lasting memories.

Determining Appropriate Technique(s)

Once the audience has been identified, the next step is determining an appropriate method or communication technique to use to best reach that audience. Is a publication or exhibit going to be most accessible? Will a personal science presentation be possible? For a small community or village, is there an existing communication medium being used, like a TV or radio station, or local newspaper or bulletin? Are mailing addresses available, emails, or phone contacts? Taking the time to figure out what will work best for each group will make any outreach much more effective. Often, there may be a combination of several strategies that could work in tandem.

Listening to the Ice

In Kenai Fjords National Park, the science of global warming and climate change is delivered to elementary and middle-school classrooms across the United States, Canada, Australia and elsewhere, through a distance learning program, Listening to the Ice. A park ranger engages students with questions, video content, and other techniques designed to broaden their local and global understanding of climate change and leave them with a hopeful attitude about the future of the natural environment. Park rangers engage with audiences ranging from 4th graders in their classrooms, to potential visitors, and virtual travelers in retirement communities.

Interpretive Planning

For large projects, communicators will create a comprehensive interpretive plan that organizes and describes all these elements in a long-term strategy. Plans like this can be developed for all levels and regions of an organization or community. It has been done already at a national level for the National Park Service (NPS 2016b) as well as by the Department of the Interior within its climate change strategy (DOI 2021).

These plans, called Interpretive Concept Plans, help to define and develop key messages and communication strategies for telling a park’s significant stories and engaging the various audiences with ways they can learn about, experience, and enjoy those stories before, during, and after their visits to the park. The development of the plan itself is a communication exercise that benefits all parts of a park’s community and is revised periodically over time.

In this case, the science (about glaciers) presented here not only pertains to the glaciers experienced at this park, but as an example of glaciers throughout Alaska.

Kennicott Glacier Interpretive Concept Plan

Of the thousands of glaciers in Alaska, the Kennicott Glacier in Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve is one of the most easily accessible to visitors. It is dynamic and shrinking rapidly, which presents an opportunity, if not an imperative, to interpret these changes and their drivers (e.g., climate change). Because Kennicott Glacier is so accessible, and the changes it is undergoing are generally typical of other non-tidewater glaciers in the state, it can also be a springboard to talk about what we are learning about glaciers in Alaska generally.

One of the most common questions asked of interpretive staff in Kennecott (pointing to the debris-covered toe of the glacier) is: “Are those mining tailings?” The persistence of the question demonstrates that visitors to the park are drawing vitally important, but incorrect, conclusions about the roles of both mining and glacier change in the evolution of the natural environment in the Kennicott Valley. Until recently, there was no systematic effort to collect and present to staff, or directly to the visitors themselves, a coherent, accessible, and accurate depiction of the central role that the Kennicott Glacier plays, and has played, in the cultural and ecological history of the Kennicott Valley. The valley provides an exceptional opportunity to interpret the role that climate change is playing in the evolution of the nation’s largest national park.

For these reasons, in 2020, an interpretive plan was developed to help the park provide visitors with an understanding of the extent, nature, and consequences of glacier change in Alaska, and the Kennicott Glacier specifically. Part One describes the purpose and significance of the plan, identifies the intended audiences, and introduces interpretive themes. Part Two describes the interpretive opportunities that are geographically based within the existing (or planned) infrastructure of the valley. It includes both on-site interpretive opportunities as well as virtual, web-based outreach, personally delivered and self-directed.

The park has committed to actions in this plan and is starting implementation in 2023. One new product will help answer the previously mentioned question of “Are those mine tailings?” in the form of an interpretive wayside. Park staff take the visitors’ most commonly asked questions and answer them on an interpretive sign. The sign addresses the dramatic changes that have been observed, using historical context and stories from those that lived in the area from the mining days to the modern era. Another technique for audience engagement being considered, is a citizen science product that allows visitors to play a part in capturing change, firsthand. Chronolog is a product that allows visitors to snap a photo, upload it, and then the photo becomes a part of a timelapse of the scenery that can be viewed online. In this case, the photo-taking platform would be placed within view of the Kennicott Glacier and visitors would play a part in capturing glacier change.

A Direct Link to Science

The theme and messages used in communication products about science issues depend on close collaboration between interpreters and scientists. A specific benefit of the Earth to Sky partnership is the enhanced relationship it enables with a wide diversity of world-class climate scientists. Since 2015, NASA’s Arctic Boreal Vulnerability Experiment (ABoVE), has involved hundreds of scientists in a large-scale study to examine environmental change across the Arctic. They seek to gain a better understanding of the vulnerability and resilience of ecosystems and society to this changing environment. Through the partnership with Earth to Sky, interpreters and educators have learned how ABoVE field-based and process-level studies by scientists help provide a foundation to better understand and predict future changes and their implications across the Arctic. As the research campaign enters its third and final phase, new communication products will be developed to share these results with many audiences.

NPS/WEEBEE ASCHENBRENNER

Pretty Rocks: A Denali Challenge

Geologists have documented the Pretty Rocks landslide in Denali National Park and Preserve which has been active since at least the 1960s. In recent years, it has evolved from a minor maintenance issue to a substantial visitor safety concern. Based on climate data from 1950 to 2010, the park has experienced a temperature increase of 7.7°F, one of the largest increases among all national parks (Gonzales et al. 2018). This increase in mean annual temperatures combined with heavy precipitation events is causing permafrost to thaw, resulting in the recent acceleration of many landslides in the area (Swanson et al. 2021).

Prior to 2014, the Pretty Rocks landslide only caused small cracks that required moderate maintenance every 2-3 years. In recent years, the rate accelerated from inches per year prior to 2014, to inches per month in 2017, inches per day in 2019, and up to 0.65 inches per hour in 2021 (see more on the Denali National Park and Preserve website). Due to climate change, a problem previously solved by minor road repairs has become difficult to overcome with short-term solutions. Since 2021, interpreters have been posted at the road closure to communicate the issue to park visitors.

One of the most effective communication approaches about Pretty Rocks has resulted from those roving interpreter contacts with visitors at the point of the road closure in the park. Visitors are informed and encouraged to make the 2.5 mile hike up to an overlook on the park road where they can experience for themselves the site of the landslide. Their amazed reactions and personal accounting of the experience, have been universally moving and supportive of the park. Time-lapse videos showing the movement of the slope have also been very effective communication products. No doubt, personal engagement with this and other evidence of climate change will continue to be important tools for park staff.

Instilling Hope

Global temperatures are warming and many ecosystem changes are occurring rapidly, especially at higher latitudes. One message coming from scientists and northern communities is that changing climate is a task society must address sooner rather than later.

Interpreters know it’s important to explain the science, the changes happening on the landscape, and the reasons why, but that’s only half their task. They aspire to inspire; to provoke audiences to care for the resources at risk. Societal action is the ultimate measure of success for effective communication.

David Orr, longtime poetry critic for the New York Times, said: Hope is a verb with its shirtsleeves rolled up (Good News Network 2022). When interpreters create products with the above principles effectively addressed, the results will inspire people to action. And those actions will give us all hope for the future.

References

Alaska Coastal Rainforest Center. 2022.

Juneau’s Changing Climate and Community Response. Supported by the U.S. Geological Survey Alaska Climate Adaptation Science Center, U.S. Department of the Interior. 53 pp.

Beck, L. and T. T. Cable. 1998.

Interpretation for the 21st Century: Fifteen guiding principles for interpreting nature and culture. Sagamore Publishing. 242 pp.

Department of the Interior (DOI). 2021.

Climate Action Plan. Department of the Interior, Policy Statement for Climate Adaptation and Resilience. 30 pp.

Furr, G., C. Lamborn, A. Sisneros-Kidd, C. Monz, and S. Wesstrom. 2021.

Backcountry visitor experience and social science indicators for Glacier Bay National Park. Natural Resource Report NPS/GLBA/NRR—2021/2301. National Park Service, Fort Collins, Colorado.

Gonzalez, P., F. Wang, M. Notaro, D. J. Vimont, and J. W. Williams. 2018.

Disproportionate magnitude of climate change in United States national parks. Environmental Research Letters 13(10): 104001.

Good News Network. 2022.

Quote of the Day, October 15. Available at: https://www.goodnewsnetwork.org/david-orr-quote-about-hope/# (accessed December 21, 2022)

Leiserowitz, A., E. Maibach, S. Rosenthal, J. Kotcher, J. Carman, L. Neyens, T. Myers, M. Goldberg, E. Campbell, K. Lacroix, and J. Marlon. 2022.

Climate Change in the American Mind, April 2022. Yale University and George Mason University. New Haven, CT: Yale Program on Climate Change Communication.

National Park Service (NPS). 2016a.

Interpreting Climate Change Self-Study Modules, National Park Service Interpretive Development Program and Climate Change Response Program.

National Park Service (NPS). 2016b.

National Climate Change Interpretation and Education Strategy. Washington, DC.

Swanson, D. K., P. J. Sousanes, and K. Hill. 2021.

Increased mean annual temperatures in 2014-2019 indicate permafrost thaw in Alaskan national parks. Arctic, Antarctic, and Alpine Research 53: 19.

Tilden, F. 2008.

Interpreting Our Heritage, 4th revised edition. The University of North Carolina Pres. 224 pp.

Toomey, A. H. 2023.

Why facts don’t change minds: Insights from cognitive science for the improved communication of conservation research. Biological Conservation 278: 109886.

Last updated: September 6, 2023