Part of a series of articles titled Reckoning with a Warming Climate.

Article

Stories Yet Told: Alaska’s Cultural Heritage in a Time of Unprecedented Climate Change

NPS/SHINA DUVALL

This article presents a select review of some National Park Service (NPS) projects and initiatives underway across parks in Alaska and in partnership with Alaskan communities that endeavor to respond to the impact of climate change on heritage sites and cultural resources.

Alaska is Vast and Extraordinary

The state of Alaska encompasses over 663,000 square miles (an almost-unfathomable 365 million acres) and has more miles of coastline than the entire lower-48 coastline combined. There are over 54.6 million acres within the exterior boundaries of the National Park System units in Alaska, which together constitute 65% of the entire system. Most of these lands are in federal ownership, but there are also private, state, borough, and municipally owned lands therein. Private lands include those held by Alaska Native Corporations, which are the largest non-federal landowner of lands within the boundaries of NPS units in Alaska. At 13.2 million acres, Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve is the largest unit in the system. On top of this, Alaska has seven of the ten largest national parks in the system, which in addition to Wrangell-St Elias, include Gates of the Arctic, Denali, Katmai, Glacier Bay, and Lake Clark national parks and preserves, and Kobuk Valley National Park.

Alaska’s Cultural Heritage is Irreplaceable

The archeological record is catching up with Alaska Native oral history and traditional knowledge, which maintains that people have been here since time immemorial. Contemporary and historical data compiled by Indigenous Elders, scholars, and scientists, combined with data gathered from the arch-eological record, paleogenomics, linguistics, and related disciplines, all indicate that Alaska is perhaps more accurately the First Frontier (not the “Last”) in the peopling of the Americas and the Western Hemisphere (e.g., Amos 2018, Aquino 2022, Keats 2021, Nicholas 2018, Taylor and Running Horse Collin 2023). Within the modern boundaries of the state are some of the oldest dated archeological sites in the Americas. An understanding of the depth and breadth of human history in Alaska informs our global understanding of human evolution, migration, occupation, adaptation, and cultural change around the planet.

In addition to the deep Indigenous past in Alaska as well as contemporary sites and landscapes of continuing cultural significance to Tribes, the state also holds innumerable stories to be told through the cultural heritage sites of a more recent past. These include the material and structural remains of exploration and colonization by Russian America and the United States, the spread of Russian Orthodoxy and other denominations of Christianity, a long history of military activity and resource extraction, settlement, transportation, fishing and the cannery industry, the gold rush, reindeer and fox farming, the fur industry, forestry, voting rights, statehood, the impacts of earthquakes and other natural disasters, ANCSA, ANILCA and conservation lands, subsistence, wilderness, the Trans-Alaska Pipeline, the Exxon-Valdez Oil Spill, tourism, dog mushing and the Iditarod, and more.

The significance of heritage and history in Alaska cannot be overstated. The Alaska Office of History and Archaeology/State Historic Preservation Office maintains a statewide data repository called the Alaska Heritage Resources Survey (AHRS). The AHRS is a primary source of cultural resources data in the State of Alaska. The database contains information on approximately 45,000 reported cultural resources (archeological sites, buildings, structures, objects or locations, and some paleontological sites) within the state. While this number of records may seem like a lot, it is estimated that only 5% of the state has been inventoried for the presence of cultural resources, which means that we simply do not know the number or density of cultural resource localities for the remaining 95%. The profoundly dynamic nature of environmental and depositional processes in Alaska, as well as obstacles to pedestrian terrestrial access further limit our ability to gain a complete understanding of the presence of cultural resources on the landscape in this state.

Climate Change and Cultural Heritage in Alaska

We know that the size and scale of Alaska is immense and the significance of Alaska’s cultural heritage to our understanding of the human experience is unparalleled. Equally astounding are the current statistics about the rate of climate-influenced change that the state is facing. According to the Fourth National Climate Assessment (USGCRP 2017), Alaska has been warming twice as quickly as the global average since the middle of the 20th century. Alaska is also warming faster than any U.S. state (Llanos 2007).

A report entitled, Alaska’s Changing Environment (Thoman and Walsh 2019) observes that climate change threatens dire consequences for many Alaska Native villages in remote areas, where subsistence hunting, fishing, and gathering are critical to livelihoods. The report states that since 2014, there have been 5 to 30 times more record-high temperatures set than record lows.

As noted by Holtz and others in 2014:

Climate change is threatening not only native Alaskan communities—many of which go back thousands of years—but also some of the oldest archaeological sites in the Western Hemisphere.

Most of the work highlighted in the remainder of this article focuses on archeological resources, but similar efforts are underway at other sites of cultural significance, including historic built environment resources (buildings, structures, monuments), cultural landscapes, and ethnographic and subsistence resources (see Mason and Craver, this issue).

Cultural Resources in Alaska’s National Parks are Threatened by Climate Change Impacts Now

It is crucial to note that—as with the rest of the planet—all areas of Alaska are experiencing a remarkable range of climate-related impacts from many stressors. These stressors include, but are not limited to: temperature change, increasing freeze-thaw cycles, permafrost melt, higher relative humidity, increased wind, increased wildfire, changes in seasonality and phenology, species shift, invasive species/pests, increased precipitation, drought, increased flooding, inundation, storm surges, coastal and riverine erosion, higher water tables, salt water intrusion, extreme weather events, pollution, development pressures, and ocean acidification (Rockman et al. 2016). There is considerable overlap in the types of stressors as well as the approaches that park cultural resource managers and staff take toward response, treatment, and adaptation to these stressors across national parks in Alaska.

Bering Land Bridge National Preserve and Cape Krusenstern National Monument

NPS staff and researchers have long been monitoring the impact of erosion on archeological sites at Bering Land Bridge National Preserve. Most recently, between 2012 and 2016, a multi-year survey documenting climate change impacts at coastal archeological sites was initiated in Bering Land Bridge National Preserve. Thus far, the research has identified severe threats to sites located along the coasts, most of which are extremely vulnerable to coastal erosion. Beginning in 2024, park staff will undertake an important project that builds upon this past work. The ensuing project represents a collaborative effort among NPS, Portland State University, Kawerak (a regional non-profit organization), and other cultural resource management groups. Previously inventoried threatened coastal sites will be revisited for limited testing and non-invasive documentation. The goal of the project is to assess site condition, to establish site significance, to continue monitoring the impacts of coastal erosions upon the sites, and to proactively work with local communities to help prioritize site mitigation.

Similarly, for the past several years, researchers at Cornell University have been collecting permafrost depth data at two study locations in Bering Land Bridge National Preserve and Cape Krusenstern National Monument. Researchers are concerned that impacts to buried cultural material resulting from changing permafrost in the region is worse than originally expected and is likely accelerating to a point or irreparable damage or loss. In the coming years, NPS staff at these Western Arctic Parklands will collaborate with Cornell to support ongoing research to further develop an understanding of the extent of permafrost loss and its impact upon buried cultural features at these sites. Several additional study locations will be established to monitor seasonal (early summer and early fall) and annual permafrost depths and to quantify the rates and levels of permafrost change. Many of the subject sites have already indicated signs of impacts to buried cultural resources resulting from changing permafrost (Junge 2022). The goals of the project will be to develop a management plan for archeological resources located in areas where permafrost is changing and to develop measures to mitigate effects.

NPS/PHOEBE GILBERT

Denali National Park and Preserve

As in other parks in Alaska and the lower-48, archeologists at Denali have observed artifacts that have likely eroded out of permafrost or ice patches due to overall warming. As these frozen contexts melt, we risk the permanent loss of highly significant artifacts, such as these organic tools (pictured below), believed to be around 1,000 years old (Gilbert 2022). The top artifact was found floating in a river and the bottom one was found in a high mountain pass. It was extremely fortunate that they were observed and collected as they have the potential to inform us about past human behavior in the region. When artifacts like this are found in this manner, we’ve already lost the most significant archeological data, which is the context in which the artifact was originally located.

Another highly publicized issue in Denali, which has caused an enormous impact on visitor use, the natural environment, and to cultural resources in the vicinity, is the Pretty Rocks Landslide. This epic landslide intersects the Denali Park Road at Mile 45.4. It has completely covered a 90 m-long stretch of the road and caused the park to close road access to the park past Mile 43 at least through the summer of 2024. As stated by NPS:

The Pretty Rocks landslide has been active since at least the 1960s, and probably since well before the Denali Park Road was built through this area in 1930. Before 2014, the landslide only caused small cracks in the road surface and required moderate maintenance every 2–3 years. Prior to 2014, road maintenance crews noticed a substantial speed up. By 2016 the movement had increased further, a slump had developed in the road, and a monitoring program was begun. The rate of road movement within the landslide evolved from inches per year prior to 2014, to inches per month in 2017, inches per week in 2018, inches per day in 2019, and up to 0.65 inches per hour in 2021.

Based on climate data from 1950 to 2010, Denali has experienced an overall average temperature increase of more than 7°F, which is the highest of all national parks.

The impacts of the Pretty Rocks Landslide to the visitor experience, as well as to the geology and other natural resources of the area are perhaps obvious. Less obvious however, is the impact of this and similar events to cultural resources. The Denali Park Road is a unique and highly significant linear cultural resource that is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. At 92.5 miles long, it has served as the backbone of the park’s circulation system since construction began in 1922. It is historically significant for its association with the period of scenic road development in national parks in the 1920s and 1930s, and with the Mission 66 park development program in the 1950s and 1960s. The road is also a rustic example of landscape engineering combining NPS aesthetic road design principles with the Alaska Road Commission’s experience constructing roads in harsh environments.

Dramatic and monumental events like the Pretty Rocks landslide have an enormous effect on the places that make up historic and cultural fabric of our parks. In this instance, the landslide has resulted in irreversible damage to the integrity of the historic Denali Park Road.

NPS/DUSTIN REFT

Heritage Assistance Program

The Heritage Assistance Program within the Cultural Resources Program at the Alaska Regional Office allows for NPS staff to provide technical support and assistance on projects outside of parks, often in collaboration with communities and partners. A group of concerned individuals and organizations, including NPS, have been monitoring the condition and integrity of the Ascension of Our Lord Church in Karluk, Alaska since at least 2002 when a non-profit organization called Russian Orthodox Sacred Sites of Alaska (ROSSIA) was formed to maintain and preserve the portfolio of historic orthodox churches in Alaska. The bluff upon which the Karluk church was constructed has been eroding rapidly for decades.

The church was built in 1888. The churchyard also contains associated outlying structures, archeological remains associated with the 6,000+ year occupation of the area, and the community cemetery. In March of 2020, the partners monitoring the church, including the community of Karluk, ROSSIA, NPS, and others, realized that the situation had become dire. A huge consortium of partners and supporters joined forces to save the church, and in August of 2021, the church building was physically moved approximately 80 feet inland, away from the bluff edge (duVall 2021).

As technical support partners on the effort, NPS has provided guidance to the community and ROSSIA on site planning, architectural documentation, and historic preservation, as well as archeological monitoring during the move to ensure no disturbance to burials or other cultural deposits located on the church grounds. We continue to support the project partners as they work to identify a new, permanent location for the church and community cemetery.

NPS/SHINA DUVALL

Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park

At Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, park archeologists are collaborating with community and Tribal cultural resource specialists at the Skagway Traditional Council to swiftly but methodically complete emergency salvage excavation at the historic Townsite of Dyea. A hallmark site that contributes greatly to the significance of the Chilkoot Trail and Dyea National Historic Landmark (NHL), this once-booming gold rush townsite (1897-1898) is threatened by erosion caused by severe flooding and aggressive course changes along the Taiya River since it was largely abandoned in the early 1900s. The townsite and vicinity are also the traditional homelands of the Chilkoot and Chilkat Tlingit, who call the area Skaqua or Shgagwéi, which means a windy place with “white caps on the water” (Brady 2013).

Within the last couple of years, the cutbank bordering the north edge of Dyea began to erode at a rate exponentially faster than at any time since the townsite was occupied. In 2021, 125 linear feet and 64,000 square feet of land was lost to the river. In 2022, an additional 235 linear feet and over 97,000 square feet of land was lost. It is conservatively anticipated that the park will lose an additional 125-150 linear feet in 2023. By comparison, prior to 2021, the average annual cutbank loss was 66 linear feet per year. To demonstrate the pace of loss, during active data recovery in the 2022 field season, 1x2 meter excavation units were obliterated by the unceasing cutbank loss within days of having been dug.

In addition to the accelerated efforts to recover archeological data at the Dyea Townsite, relentless flooding is severely and adversely affecting known and as-yet undocumented cultural resources as well as modern park infrastructure all along the Chilkoot Trail. The current Taiya River flooding and channel migrations are a result of:

- an increase in overall discharge related to climate change (higher precipitation as well as glacial melt),

- the shift of a braided channel system into a single powerful channel (related to reforestation post-gold rush as well as climate change), and

- bank modifications in the lower reaches (namely the bank armoring the dike at Taiya River bridge).

NPS/JASON ROGERS

Lake Clark National Park and Preserve

Archeologists and cultural resource staff at Lake Clark National Park and Preserve are working to document the Clam Cove Pictograph Site, which is one of only two pictograph sites in Lake Clark (Baird et al. 2022). The Clam Cove site was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2017.

Archeological research and Carbon-14 dates obtained from organic artifacts collected from the site in the late 1960s suggests a late Holocene occupation at the site (c. 1,700 radiocarbon years ago; Baird et al. 2022). The pictographs consist of anthropomorphic body shapes, zoomorphic images (mainly sea mammals), boats, and abstract markings. The pictograph site is presently threatened by generally warmer temperatures in the region, which is causing increased water runoff, increased vegetation growth in the immediate vicinity of the site, spalling of the rock face, increased lichen growth on the surface, and water percolating directly through the sandstone substrate of the rock upon which the pictographs are located. The stressors present at the site, which are a direct result of climate change effects, have been quantified over the past 15+ years by park staff through both anecdotal and photographic evidence.

Although park staff can do little to ameliorate conditions or mitigate the threats at the site, a conservation plan was developed for the site (Shah 2006), and the park continues to document existing conditions and the ongoing changes at the site, while also keeping Tribal groups and gateway communities informed of the site conditions.

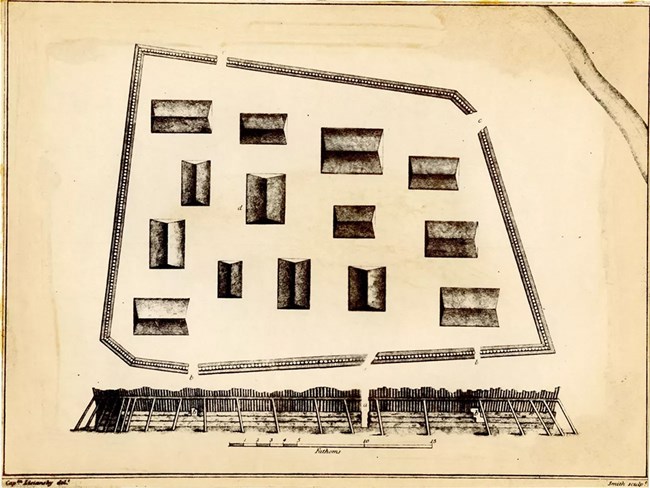

Sitka National Historical Park

The Kiks.ádi Fort Site, or Shís’gi Noow, is the location of the Battle of 1804, a “watershed moment in the history of Alaska and Russian America” (Hope 2008). Named for the most powerful of the Sitka Tlingit clan houses, the Kiks.ádi successfully fought off a Russian advance on the territory at this location. The Fort Site is also directly associated with the Survival March, which resulted in the loss of land, homes, possessions, and clan regalia by the Kiks.ádi Tlingit and caused them to remain away from their home for 18 years.

The Kiks.ádi Fort Site and Battleground has been archeologically documented intermittently over the years since the park was established, but a current project is underway to confirm past survey findings in order to more confidently affirm the exact location of the fort walls. This effort is critical now as the fort site is threatened by erosion and an existing revetment repair project is planned at the site.

The Kiks.ádi Fort Site and battleground has been protected from erosion by a riprap revetment since 1985, when it was determined that the natural course of the Indian River would continue to erode at a rate of 3-6 meters per year, destroying the historic cultural landscape (Perkins 2022). The revetment remained undamaged until a huge rain event in 2015, which raised the river level significantly above flood levels and caused substantial damage to the revetment. Extreme increases in rainfall and extraordinary precipitation events are significant climate stressors in the region. Park staff plan to completely reconstruct approximately 150 feet of the revetment along the river. The Park continues to consult with the Sitka Tribe of Alaska and other potential consulting parties regarding the design and implementation of the project, which is scheduled to be completed in 2027.

Alaska’s Cultural Heritage Challenges Going Forward

Despite the commendable work that is occurring now at parks in Alaska, considerable obstacles and deficiencies persist that prohibit us from assuming a greater lead in areas of assessment, treatment, and adaptive response to climate impacts on our cultural heritage.

To get out ahead of the changes we are experiencing in the region—to be proactive instead of reactive—our needs are numerous. And they must be coordinated with other regions and at the service-wide level to be effective. We simply cannot accomplish meaningful progress —which is difficult in and of itself to define given the rate and extent of change—without a wholesale commitment of resources and energy toward these ends: partner engagement and collaboration, condition and vulnerability assessments, prioritization of needs, resource documentation, and where necessary, mitigation of loss.

To complete this work in Alaska, we need to be able to access remote field locations where limited to no road access is available. This means travel via helicopter, small plane, or by watercraft. We must continue and build upon existing climate futures planning efforts to anticipate and visualize response, build resiliency, and maintain continuity of operations in the face of increasing and overlapping climate stressors and threats. We desperately need improved spatial modeling, data management, and digitization tools that allow us to conduct robust risk analysis and ranking of need, both in the field and within our collections. In collections and facilities, we need improved and more routine emergency response and evacuation training, including inter- and intra-regional disaster response and recovery solutions for cultural resources staff. We need to integrate even more closely with our community and Tribal partners, as well as our NPS colleagues in subsistence, natural resources, law enforcement, environmental planning and compliance, interpretation and education, and other departments to move forward toward shared goals, and to generate meaningful outcomes in collaboration and co-stewardship. Sadly, we must also learn together when and where it will be necessary to accept the inevitability of loss.

We are not just cultural heritage professionals. We are also residents and responsible caretakers of this place which is steeped in extraordinary history and culture. We care deeply about the places and cultural practices that together form the fabric of this unique state. As we face the enormous test that is climate change in the 21st century, may we keep in mind the words of Katie John (1915-2013), a beloved Ahtna Athabascan Elder and champion of Alaska Native rights:

I don’t know if any of us really know what we are capable of until it comes to it.

—Katie M. John

NPS/KEN HILL

References

Amos, J. January 3, 2018.

Alaskan infant’s DNA tells story of ‘first Americans.’ Available at: Alaskan infant’s DNA tells story of ‘first Americans’ - BBC News (accessed June 2023)

Aquino, L. October 28, 2022.

Community Archeology Helps Bridge Gap Between Science and Tradition. Available at: Community Archeology Helps Bridge Gap Between Science and Tradition | Smithsonian Voices | National Museum of Natural History Smithsonian Magazine (accessed June 2023)

Baird, M. F., M. L. Moss, S. Perrot-Minnot, and J. Rogers. 2022.

The Archaeology of Clam Cove, Lake Clark National Park and Preserve, Southcentral Alaska. Alaska Journal of Anthropology 20(1-2): 85-102.

Brady, J. 2013.

Skagway: City of the New Century. Lynn Canal Publishing.

Braje, T. E. Elliott Smith, J. Meling, and T. Rick. 2023.

Can archaeology help restore the oceans? Sapiens. Available at: https://www.sapiens.org/archaeology/archaeology-sustainability-channel-islands/ (accessed August 30, 2023)

duVall, Shina. 2021.

How We Rescued the Ascension of Our Lord Church in Karluk, Alaska, from Falling off a Cliff. Park Science 35(1).

Gilbert, P. November 2022.

Presentation to NPS Alaska Cultural Resources Advisory Committee on ongoing projects in Denali National Park & Preserve.

Haaland, D. 2021.

Department-Wide Approach to the Climate Crisis and Restoring Transparency and Integrity to the Decision-Making Process. Secretarial Order 3399. Available at: SO 3399 Climate Crisis _Transparency and Integrity to Decision-Making Processes (doi.gov) (accessed June 2023).

Holtz, D., A. Markham, K. Cell, and B. Ekwurzel. 2014.

Native Villages and Ancestral Lands in Alaska Face Rapid Coastal Erosion. Pages 47-49 in National Landmarks at Risk: How Rising Seas, Floods, and Wildfires Are Threatening the United States’ Most Cherished Historic Sites. Union of Concerned Scientists.

Hope, H. 2008.

The Kiks.ádi Survival March of 1804. Pages 273-285 in N. Marks Dauenhauer, R. Dauenhauer, and L. T. Black, eds. Anóoshi Lingít Aaní Ká/Russians in Tlingit America: The Battles of Sitka, 1802 and 1804. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Junge, J. November 2022.

Presentation to NPS Alaska Cultural Resources Advisory Committee on ongoing projects in Bering Land Bridge National Preserve and Cape Krusenstern National Monument.

Keats, J. February 8, 2021.

How Indigenous Oral Tradition Is Guiding Archaeology and Uncovering Climate History in Alaska. Available at: How Indigenous Oral Tradition Is Guiding Archaeology and Uncovering Climate History in Alaska | Discover Magazine (accessed June 2023).

Llanos, M. July 6, 2007.

Alaska, the first frontier for warming in U.S. Available at: Alaska, the first frontier for warming in U.S. (nbcnews.com) (accessed June 2023).

Nicholas, G. February 21, 2018.

When Scientists “Discover” What Indigenous People Have Known For Centuries. Available at: When Scientists “Discover” What Indigenous People Have Known For Centuries | Science| Smithsonian Magazine (accessed June 2023).

Perkins, J. November 2022.

Presentation to NPS Alaska Cultural Resources Advisory Committee on ongoing projects in Sitka National Historical Park.

Rockman, M., M. Morgan, S. Ziaja, G. Hambrecht, and A. Meadow. 2016.

Cultural Resources Climate Change Strategy. Washington, DC: Cultural Resources, Partnerships, and Science and Climate Change Response Program, National Park Service.

Sams III, C. F. 2022.

Statement of Charles F. Sams III Director, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior Before the Subcommittee on Interior, Environment, and Related Agencies of the Committee on Appropriations, U.S. House of Representatives. May 18, 2022. Available at: HHRG-117-AP06-Wstate-SamsC-20220518.pdf (house.gov) (accessed June 2023).

Scheidel, Arnim, et al. 2023.

Global impacts of extractive and industrial development projects on Indigenous Peoples’ lifeways, lands, and rights. Science Advances 9(3): eade9557.

Shah, M. 2006.

Preservation Plan for Tuxedni Bay and Clam Cove Pictograph Sites, Lake Clark National Park and Preserve. Report on file at the National Park Service / Lake Clark National Park and Preserve, Alaska Association for Historic Preservation, Anchorage.

Stoddart, M., J. Cherner, and D. Dwyer. 2021.

Haaland embraces ‘indigenous knowledge’ in confronting historic climate change impacts. Available at: Haaland embraces ‘indigenous knowledge’ in confronting historic climate change impacts - ABC News (go.com) (accessed June 2023).

Taylor, W. and Y. Running Horse Collin. March 30, 2023.

Archaeology and genomics together with Indigenous knowledge revise the human-horse story in the American West. Available at: Archaeology and genomics together with Indigenous knowledge revise the human-horse story in the American West (theconversation.com) (accessed June 2023).

Thoman, R. and J. E. Walsh. 2019.

Alaska’s changing environment: Documenting Alaska’s physical and biological changes through observations. H. R. McFarland, Ed. International Arctic Research Center, University of Alaska Fairbanks.

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. n.d.

Statement on the effects of climate change on Indigenous peoples. Available at: Climate Change | United Nations For Indigenous Peoples) (accessed June 2023).

U.S. Global Climate Research Program (USGCRP). 2017.

Climate Science Special Report: Fourth National Climate Assessment, Volume I [Wuebbles, D. J., D. W. Fahey, K. A. Hibbard, D. J. Dokken, B. C. Stewart, and T. K. Maycock, eds.]. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, USA, 470 pp.

Select critical reading

Daly, C. 2014.

A Framework for Assessing the Vulnerability of Archaeological Sites to Climate Change: Theory, Development, and Application. Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites 16(3): 268-282.

Dawson, T., C. Nimura, E. López-Romero, and M. Daire, eds. 2017.

Public Archaeology and Climate Change, 1st edition. Oxbow Books, United Kingdom. 208 pp.

Jarvis, J. B. 2014.

Policy Memorandum 14-02, Climate Change and Stewardship of Cultural Resources. National Park Service. Available at: https://www.nps.gov/policy/PolMemos/PM-14-02.htm (accessed June 2023)

National Park Service. 2010.

National Park Service Climate Change Response Strategy. National Park Service Climate Change Response Program, Fort Collins, Colorado.

Wright, J. P. and Morris Hylton III. 2022.

Plan the work, work the plan: An introduction to the National Park Service Climate, Science, and Disaster Response Program. Parks Stewardship Forum 38(3): 389-411.

Xiao, X., P. Li, and E. Seekamp. 2023.

Sustainable adaptation planning for cultural heritage in coastal tourism destinations under climate change: A mixed-paradigm of preservation and conservation optimization. Journal of Tourism Research.

Tags

- bering land bridge national preserve

- cape krusenstern national monument

- denali national park & preserve

- klondike gold rush national historical park

- lake clark national park & preserve

- sitka national historical park

- alaska

- aps

- alaska park science

- cultural resource protection

- cultural resources

- climate change

- climate change impacts

Last updated: January 2, 2024