Last updated: September 12, 2025

Article

Anne Castellina

NPS Photo

A New Style of Leadership

Selected as Kenai Fjords National Park’s superintendent in January 1988, she quickly took steps to integrate the park into the local community. In her first week, she joined the Rotary Club, a local service-focused non-profit, which proved to be her first steps in becoming a citizen of Seward. Anne felt strongly that the park and the town stood to benefit each other. Anne once told an interviewer, “Becoming part of things just seemed natural; I felt like I’d come home.” She encouraged her staff to get involved in community activities. “One of the things we [in the Park Service] haven’t done so well is to recognize that while we’re involved in managing a parkland, we’re also part of a human community,” Anne said. “We need to participate in that, too.”Her encouraging management style contributed to the creation of a strong bond and positive working relationships among park staff. She frequently hosted dinners and game nights for staff and their families. Her own long stint of 16 years at Kenai Fjords National Park (1988-2004) was matched by similar long tenures of several other staff members. Today, Anne still sees hiring the right people and building a great team that shaped Kenai Fjords National Park in its early years as one of her proudest achievements.

NPS Photo

A Manmade Disaster

NPS Photo

The Exxon Valdez oil spill was a turning point in the history of Kenai Fjords National Park. As the first national park in the path of the oil slick, Kenai Fjords was thrust into national headlines. Anne had a strong background in communications and outreach, and whatever doubts the town leadership had about a woman being put in charge of the park were soon dispelled by Anne’s forceful leadership. She was able to unify leaders across organizations to present a common front against Exxon. Anne presented the oil spill as a shared ecological disaster that would impact the community and surrounding areas well beyond Kenai Fjords’ coast. This helped organizations and community members join together to help organize nearly three years of clean-up efforts. The whole park staff would take part on the coast: cleaning off oil-covered birds, helping with data collection, or finding other ways to support. During one of the final NPS meetings on the oil spill event, Anne recalled her all-male superintendent colleagues from around the region looking her in the eyes and saying, ‘“wow we didn’t think you could do this.’” The year 1991, Anne’s fourth as superintendent, would be the first since the oil spill that was not dominated by clean-up activities, and her first chance to manage the park more reflectively. She would continue defying expectations by capably guiding the park through thirteen more years of change and growth.

View a selection of photos of the 1989 oil spill's effects on the Kenai Fjords coast, and how people responded.

Leading with Passion

Anne and her team turned their focus back to the park as a whole and how to improve the visitor experience. The Exit Glacier Area, still the only part of the park accessible by road, was the target. Anne’s leadership and willingness to fight for funding was crucial in beginning trail development that improved visitor access to Exit Glacier and the vast Harding Icefield beyond. Throughout her time as superintendent, she worked hard to get big ideas, improvements, and new safety elements funded -making the park the best it could be so people would come and enjoy. With improved access to Exit Glacier came a need for rangers to interpret the stories of its towering blue ice and the landscape it carved.

NPS Photo

While the park had a visitor contact station and a small visitor pavilion at Exit Glacier, Anne saw an opportunity to expand opportunities for the public with more exhibits and guided programs. She worked hard to encourage interpretive opportunities, climate change conversations, and visitor connections. Years into her role she liked to take short breaks from her administrative duties to work the information desk - just to have an opportunity to talk to visitors. By the mid-1990s the interpretive program was expanding with new exhibits, audio-visual media, and ranger programs offered at Exit Glacier and the Visitor Center in the small boat harbor of Seward. The park grew new partnerships, working together with boat operators, the Alaska Sealife Center, the NPS Oceans Alaska Science and Learning Center (OASLC), amongst others. Anne’s commitment to building community and relationships inspired collaboration to be a key value of Kenai Fjords National Park’s Interpretation program for the remainder of her tenure and beyond.

A Legacy of Love

NPS Photo

Anne's love for community helped this park and its employees thrive. She was a powerful leader that worked hard to make Kenai Fjords National Park into a place to love. From 1988 to 2004, her work molded Kenai Fjords National Park into what visitors enjoy today. With a closer look, you can still see that legacy. In 1992, she convinced the regional office to pool available fund to purchase the Serac, a boat that remains critical to park operations 32 years later. The cabins you can reserve along the coast and at Exit Glacier were funded in 1992 when Anne claimed the majority of Senator Stevens budget to construct public use cabins across Alaska’s National Parks. Noting that most of the park resources were along the coast and much of the visitation to the park was also along the coast, Anne expanded the resource management staff to include coastal ecology. Those hired during and after her tenure have worked continuously to understand not only visitor use, but the life teeming amongst the fjords and how to protect it. In 2000 Anne’s proposal for a science and learning center to be at Kenai Fjords National Park was approved and created in partnership with the Alaska Sealife Center. Today, the Ocean Alaska Science and Learning Center supports education and research at eleven coastal national parks and 3,600 miles of Alaskan coastline. In 2004, Anne helped the park celebrate the opening of the long-awaited Exit Glacier Nature Center, where you can still find park rangers giving a warm welcome to visitors. It would be hard to find a part of Kenai Fjords not tied to Anne Castellina’s leadership and commitment to the NPS mission. That far-reaching thread of love and home remains, supporting staff, community and visitors for generations to come.

Written by Kestrel Troutman, Park Ranger

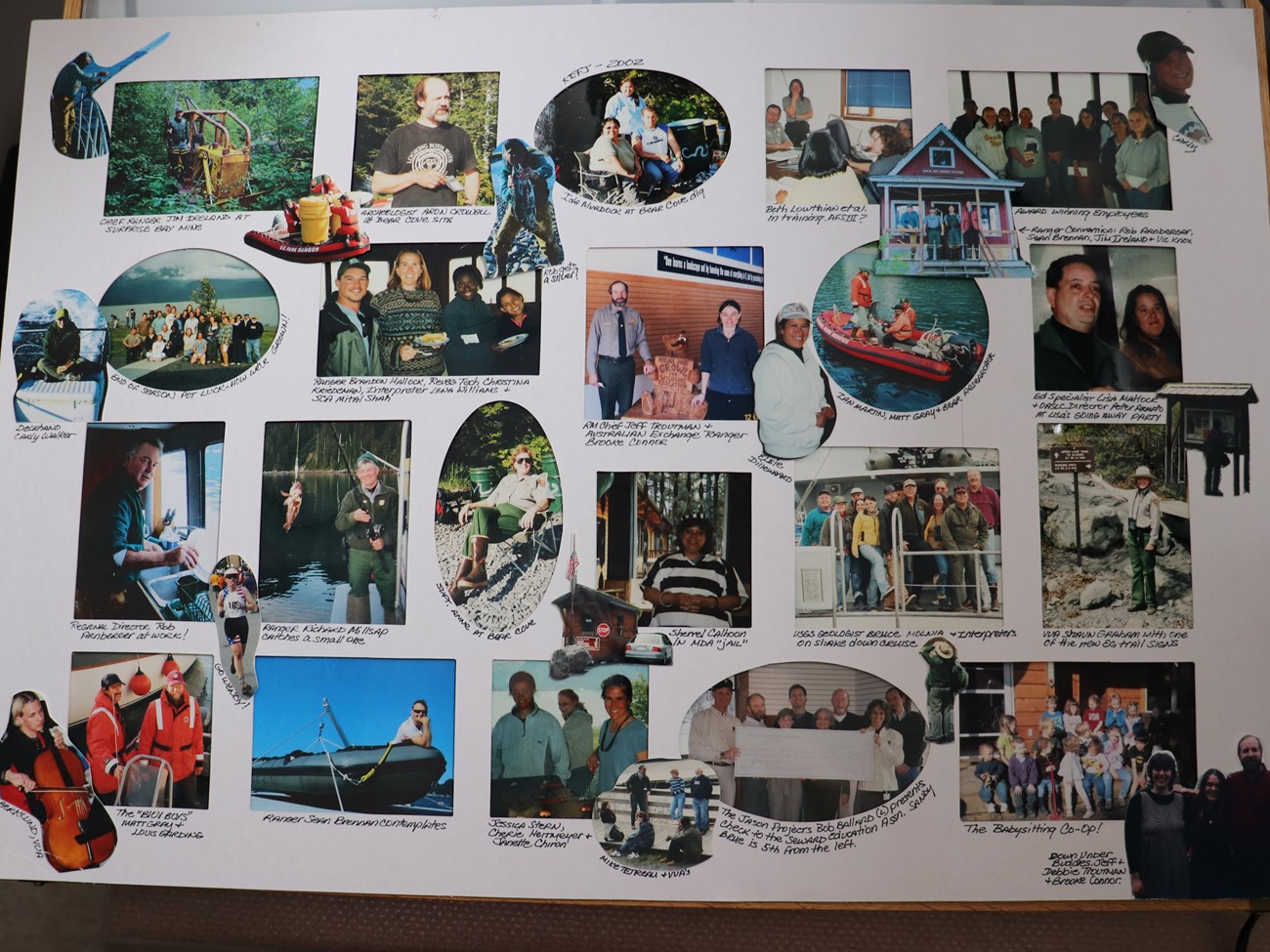

Castellina's Collages

At the end of each season, Anne created a photo collage to celebrate Kenai Fjords' community of staff. Each provides glimpses of the joy and belonging evident throughout her tenure.

NPS Images

Learn More

Where Mountains, Ice, and Ocean Meet

What are you curious about?

The story of the Kenai Fjords is not just one of geology and landforms, but also of people.