Last updated: December 19, 2023

Article

Shrinking Glaciers in Aniakchak National Monument and Preserve

Alaska is one of the most heavily glaciated areas in the world outside of the polar regions. Approximately 21,835 square miles of the state are covered in glaciers—an area nearly the size of West Virginia. Glaciers have shaped much of Alaska’s landscape and continue to influence its lands, waters, and ecosystems. Because of their importance, National Park Service scientists and partners measure glacier change. They have found that glaciers are shrinking in area and volume over nearly all the state. From 1985 to 2020, glacier-covered area in Alaska decreased by 13%. Over the same period, Aniakchak National Monument and Preserve also experienced a loss in its glacier-covered area. As our climate continues to warm, these changes will continue to occur and likely accelerate, profoundly impacting the landscape of Alaska and our parks for generations to come.

Glaciers in Aniakchak

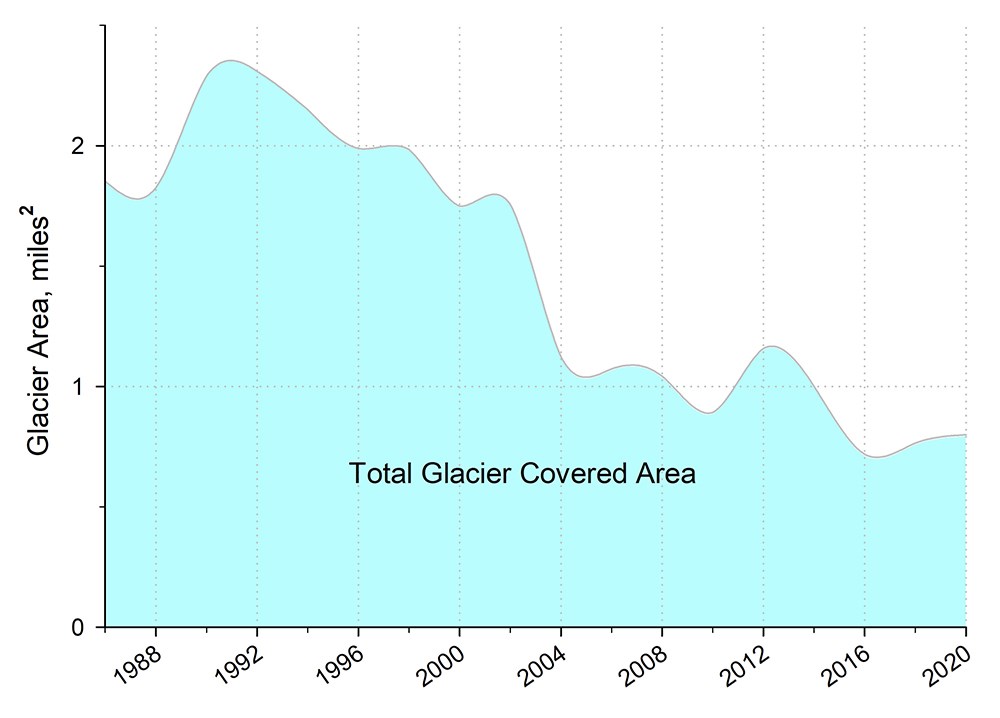

Aniakchak National Monument and Preserve, on the Alaska Peninsula, is one of nine national parks in Alaska with glaciers. Aniakchak is one of the smallest glaciated parks in the state and has one of the smallest proportions of glacier-covered area (0.1%; Figure 1). Glacier cover in Aniakchak decreased by 14% from the 1950s to the 2000s, and our most recent study found a decrease in area from 1985 to 2020 (Figure 2).

In Aniakchak, small glaciers sit on the rim of Aniakchak Crater, an active caldera (Figure 3). The largest of these glaciers is less than a square mile in area and predominantly covered with volcanic ash, either from eruptions within the caldera, or from one of the many other nearby active volcanoes. While very small, the glacier-covered area in Aniakchak is unique due to its location in the caldera of an active volcano and frequent exposure to volcanic debris.

Austin Post, U.S. Geological Survey, University of Washington Collection.

The caldera formed approximately 3,700 years ago and last erupted in 1931. The year before and after this eruption, the geologist and Jesuit priest, Father Bernard Hubbard, visited the caldera and wrote (in his book, Mush, You Malamutes!): “Last year it was a plant, fish, and animal world inside of a mountain where color and variety abounded....Now it was the abomination of desolation with everything blotted out. Glaciers and snowfields all around the twenty-one-mile rim were black.”

Statewide Glacier Change

Alaska’s high-latitude and high-elevation mountain ranges have historically had average annual temperatures cold enough to sustain glaciers. However, global air temperatures are increasing, and Alaska and other high-latitude regions are warming faster than the average global rate. Data from NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information indicate Alaska’s statewide average annual temperature has been increasing by 0.6°F per decade since 1950. As temperatures warm, the elevation at which snow and ice remain frozen is getting higher, with more rain and less snow at lower elevations. The effects are most visible at a glacier’s lowest elevations, where most glacier termini are rapidly retreating.

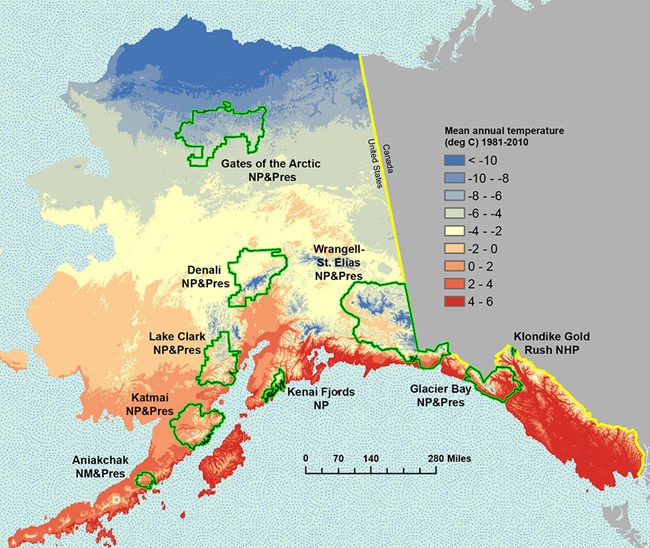

From 1985 to 2020, glacier-covered area in Alaska decreased by 13%, or 3,253 square miles (8,425 km2). Glaciers within national parks in the state (parks shown in Figure 4, along with average annual temperatures) decreased by 8% from the 1950s to the early 2000s. From 1985 to 2020, the largest changes in glacier-covered area in Alaska occurred at elevations of 2,625–7,218 feet (800–2,200 m) and in southern Alaska—the region that encompasses the greatest glacier-covered area. Little change was seen in the relatively small glaciers of the Brooks Range in northern Alaska.

Because of the importance of Alaska’s glaciers and the implications of glacier loss, including for how we manage parks, glacier monitoring and assessment will continue to be a critical, ongoing activity of the NPS and its partners.