Last updated: December 20, 2020

Article

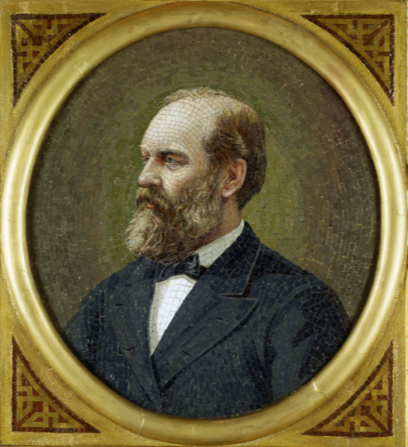

An Open and Businesslike Campaign

U.S. Senate Collection

Soon after Rutherford B. Hayes became President in March, 1877, he selected John Sherman, Senator from Ohio, to be his Secretary of the Treasury. That left an open Ohio senate seat. While the field of likely candidates was large, most Republicans in the state agreed that James Garfield was the favorite. Garfield was definitely interested, but following his usual custom, did not encourage his political friends in the state. He confessed in his journal that “I shall probably pursue my usual course of seeking nothing and letting events take care of themselves.”

“Events” came in the form of direct intervention by President Hayes. He wanted Garfield to remain in the House to lead the Republican minority, and perhaps win the Speaker’s chair. Garfield was not happy, but the President insisted, so on March 11, 1879, the Congressman wrote to his supporters in the state withdrawing his name. The work of the minority leader during the Hayes administration was taxing and occasionally bitter, and Garfield decided that he would not allow another opportunity to move to the Senate go by without a contest.

John Sherman indicated in July, 1879, that he had no interest in returning to the Senate, and would not oppose Garfield for the position. But he very much wanted the Republican presidential nomination, and Garfield’s support among Ohio Republicans at the 1880 convention. With Sherman’s behind the scenes endorsement, the next challenge was to assure a GOP victory in the state legislature. At that time, Senators were chosen by the state legislatures, so the next senator would represent the party in power there. Garfield stumped all over the state, writing to his wife from Adams County: “The audience rose and gave me three cheers for the next U.S. Senator. This has happened several times on my trip.”

Ohio voted for its legislators on October 14; the Republicans won the state Senate 21 to 15, and the House 69 to 45. Garfield’s campaign for the U.S. Senate seat began almost immediately thereafter. Garfield’s diary over the next four months clearly shows the actions he took with the support of his political friends, and more importantly, his feelings about moving from the House to the Senate and the steps he was willing to take to ensure election.

Diary, Tuesday October 21, 1879, Mentor: Spent the forenoon between my library and the potato field without doing much in either. . . Dr. Streator came to have a full talk with me on the senatorship. If I were to act upon my own choice, without reference to influences outside of my preferences, I would remain in the House of Representatives. But I have resolved to be a candidate for the U.S. Senate for these reasons:

First. I am, and as leader of the House shall continue to be, too hard worked, and am likely to break down under its weight.

Second. There are many good men in my District who will think it selfish in me to keep them out of the House when I have a fair chance of promotion.

Third. I once gave way at the request of the President, and a few fellows of the baser sort said I was afraid to risk my strength in the larger field of the state. If I decline now, I should lose still more in this direction.

Thursday, October 23, 1879, Cleveland: Spent the day in dictating 50 letters, shopping, and in holding conferences with friends on the subject of the senatorship.

A committee of three, Capt. Henry, W.S. Streator, and N.B. Sherwin have taken it in hand to find out the exact situation, by a reconnaissance of the field. I feel greatly averse to doing anything about it myself.

I feel that my services to the country should speak for themselves, rather than that I should speak for them or of them.

Perhaps the customs of the times will modify this so that I may be compelled to look after the matter myself; but I hope not.

Saturday, October 25, 1879, Mentor: . . . If money is to be used, if the Senatorship is to be bought, I am not a purchaser. But I do not believe it is for sale.

Tuesday, December 2, 1879, Washington: If the public opinion of three quarters of a century had not decided that to go from the House to the Senate is a promotion, I would prefer to stay in the House, where my leadership is unquestioned, and the speakership is almost certain to come.

Wednesday, December 31, 1879, Cleveland: At nine a.m. met several friends by appointment at the Post Office. Found that Dr. Streator had arranged to have a select party of Cleveland men go to Columbus on Friday next. . . and reconnoitre the field. Spent several hours discussing the situation, comparing notes and deciding upon a policy to be pursued by my friends. I allowed rooms to be taken at the Neil House and cigars to be kept for visitors, but no liquors of any kind, no offer of offices nor any other thing to any member for his support . . .

Friday, January 2, 1880, Cleveland: Met a large number of friends at the Post Office and held a final consultation before their departure for Columbus. It is gratifying to know that the best citizens of all parties here are earnestly in my favor . . .

Saturday, January 3, 1880, Cleveland: . . . [L]etters from Columbus, telling me of the progress of the Senatorial contest. All looks well, and I think I shall be nominated on the first ballot. Indeed, there are signs that the opposition will wholly break down, though they yet talk loud. . .

The separate caucuses of the two Houses of the Legislature are being held this evening. I sent word to my friends to have an early senatorial caucus.

Sunday, January 4, 1880, Mentor: . . . The Sunday morning papers give the result of the last evening’s caucus and say that the Senatorial Caucus is fixed for Tuesday evening next, an unusually early period, which was done on motion of my friends.. . Received a telegram from Dr. Streator asking me to go into Cleveland in the morning.

Monday, January 5, 1880, Cleveland: Went into Cleveland on the 7:50 train. . . and found at the P.O. a great mail and many friend[s]], anxious about the Senatorship. Dr. Streator has dispatches from Columbus telling him that powerful delegations are coming from Cincinnati to work for Taft and Mathews, and that there are signs of a combination of all my rivals against me. I don’t think they can beat me if they do combine, but I have asked a number of friends from here to go down to Columbus this evening and look after the allies against me. My orders are no liquor, no promises of office, or any other thing, no compromise, no delay of action, but a manly test of the question on its merits. I want the senatorship with absolute freedom, or not at all.

Tuesday, January 6, 1880, Cleveland: . . . Several dispatches came during the day which inform me that many friends from distant parts of the state are at Columbus at work for me. The spontaneous opinion of the party seems to be so strong in my favor that I do not believe the political managers can resist it. At 3:50 p.m., I learned that Gov. Denison withdrew from the contest, and it is probable that Senator Matthews and Judge Taft would do likewise. . . At 8:30 p.m. telegrams informing me that at the Legislative Caucus at Columbus, Dennison, Taft and Matthews withdrew, and I was nominated for U.S. Senator by acclamation. The manner of it is more gratifying than the nomination itself.

An observer declared that “no such scene was ever before witnessed in the State Capitol, that no Senator was ever before elected by acclamation for his first term, and that no Senatorial contest was ever before held without the candidate considering it expedient to be on hand to see how things were going.” It was, as biographer Theodore Clark Smith described it, an open and businesslike campaign. And when it was over Charles Henry, Garfield’s longtime political ally, submitted a bill for $148.60 for campaign expenses, returning an unspent $1.40 from his $50 advance to the new Senator-elect.