Last updated: April 15, 2021

Article

An End and a Beginning: St. Paul's, from church to National Park site

National Park Service

After more than three centuries, the religious activities of the parish of St. Paul’s Church terminated in November 1980, launching a reconstituted role as a national historic site.

An inquiry into the final years of St. Paul’s logically begins with the restoration of 1942, conceived as a project to sustain the parish. Over the previous generation, the Episcopal church in Mt. Vernon, New York had endured declines in size of congregation, condition of facilities and available resources. Calculating that icons endure, Rev. Harold Weigle chaperoned the restoration as a strategy to sustain the church as a religious community.

With financial support and guidance from President Roosevelt’s mother Sara, a campaign to generate funding for the project impressively raised approximately $42,000 (about $600,000 today). The re-introduction of the orientation and dimensions of the high walled box pews which had packed the church floor in the 1780s followed a pattern of re-generation envisaged most famously at Colonial Williamsburg. Utilizing the specifications of the original St. Paul’s pew plan and the architectural experience of the Boston-based firm that designed the Virginia tourist attraction, the colonial restoration was an impressive achievement.

But as a strategy to reverse the decline of the church the refurbishment failed to realize its goals. It was a physically limited formation, merely turning back the clock on the spatial layout of the church’s interior. The restoration campaign lacked a corollary drive to address the broader reasons for the decline of the parish -- the gradual but steady transformation of a centuries old residential community into an industrial corridor. Zoning laws passed years earlier had determined the composition of the surrounding community, and the trend was perhaps irreversible by the 1940s.

An unforeseen difficulty lay in the effect of the restoration. Turning the sanctuary into a monument to the 18th century layout of a church generated a large following for special historical commemorations; but it was resented by some of the regular Sunday attendees, who preferred to worship in a sanctuary corresponding with the expectations of people living in the 20th century. Some of the families in an already struggling parish departed and joined other Protestant congregations.

An additional indication of decline was the spillover from the men’s shelter adjacent to the church. Since the 1930s, the three-story facility had served as an adjunct of New York City homeless shelters, drawing men by means of the nearby Dyre Avenue subway who could not obtain beds in Manhattan shelters. Those who failed to gain admittance to the Salvation Army dormitory facilities because of a shortage of cots camped out on the church grounds, creating a scene of a sleeping park for the destitute. That unpleasant outdoor climate symbolized the decline of St. Paul’s as a location of importance and stability. It was highlighted in attention the church received in 1965, marking the 300th anniversary of the colonial parish which established St. Paul’s. A journalist visiting the Mt. Vernon site reported that the church was

entering its fourth century with about as many vagrant drunks in its cemetery at night as it has devoted parishioners in its pews on Sunday. Attendance has dwindled to an average of 17, while the old burial ground’s rising popularity for alcoholic lapses of homeless men was attested today by hundreds of empty whisky bottles and beer cans among the tombstones.

St. Paul’s continued to receive notice through articles chronicling the site’s historical significance, which usually included glib allusions to the remaining, shrinking congregation. Instances of unwarranted intrusion, vandalism and desecration reinforced an unfavorable impression of a regressing institution lacking the ability to adequately uphold the physical plant. In context, the 1960s and 1970s overlapped with widespread lapses in the maintenance of parks, landmarks, monuments and historical properties in the New York area. Public and private budgetary shortages led to reductions of resources to sufficiently preserve those places, which were increasingly characterized by deterioration and graffiti.

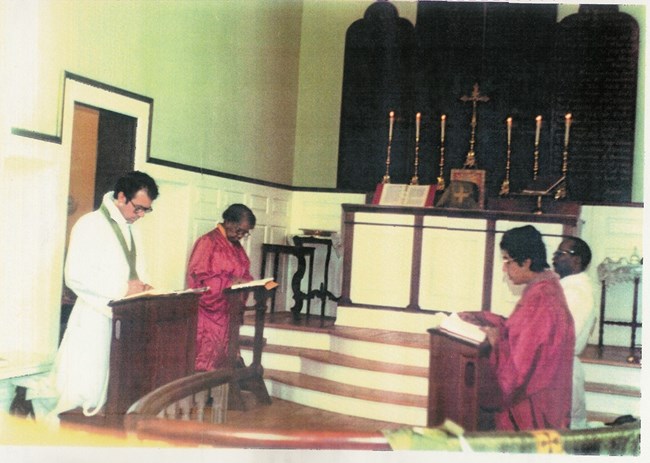

In a religious sense, St. Paul’s remained an important spiritual home for about 15-20 people. In the final two decades, the congregation was an interesting inter-racial community of white families who had grown up with St. Paul’s and a group of black Caribbean immigrants who embraced the church through the influence of a woman named Ruth Harewood. A native of Trinidad, Ms. Harewood immigrated to America in 1947, settling in the northern Bronx. She discovered St. Paul’s in the early 1960s at one of its nadirs, recalling only six worshippers kneeling in the pews on a Sunday morning. Intrigued with the stone edifice, Ms. Harewood organized transportation caravans to the church for parishioners from her neighborhood, about a ten minute drive. Like her, these members adhered to the Anglican faith on their native islands, and found a natural home in the Episcopal church. Indicating a continued role in the neighborhood, an array of church sponsored and community events enlivened the parish hall, today’s museum at St. Paul’s N.H.S.

Pious people who valued the church as a religious home “built for the good of the community, to help people,” insisted Ms. Harewood, these congregants of the 1960s and 70s lacked the personal wealth or channels to funds necessary to sustain St. Paul’s. Responsibility devolved to the Episcopal Diocese, which was overextended in Mt. Vernon. In a city shrinking in population from 76,000 in 1960 to 66,000 by 1980, or a decline of about 13-percent, St. Paul’s was one of five Episcopal parishes. This represented only one fewer than the number of Catholic house of worship in a city registering a considerable population of Italian Americans who supported those churches.

St. John the Divine, an Episcopal parish meeting in a small 20th century edifice, was only a mile away, or a four minute drive. Several of the Episcopal churches in Mt. Vernon were struggling to maintain sizable, viable congregations, and some consolidation was probably necessary. In the late 1960s, the Diocese implemented a resource sharing initiative called Christ the King, but distributing financial responsibilities for maintenance and operations among struggling churches proved inadequate. Even more challenging, families and individuals moving into the adjacent radius of southern Westchester County and the northern Bronx, the traditional St. Paul’s neighborhoods, usually preferred other Christian denominations or even different faiths. Cultural shifts also reduced attendance at religious services by younger people.

These symptoms of a church in decline are hardly exclusive to St. Paul’s in the period under discussion, and doubtless many readers of this essay could cite past or contemporary examples of similar dwindling religious communities across the country.

But the distinction lay in the additional value of St. Paul’s as a historic site that could be preserved through alternative measures. A considerable set of constituencies favored ceding the property to a historical agency; they were ultimately more influential than the small number of worshippers who hoped to sustain the parish. Local historical societies and friends’ groups advocated a transfer of the land to the Federal Government. More importantly, leaders of the Episcopal Church were interested in a conveyance of the grounds. Since the 1950s, St. Paul’s had functioned as a Mission Church, which meant the central Diocese of New York provided substantial underwriting support of operating costs. Bishop Paul Moore of the Diocese of New York and J. Stuart Whetmore, Suffragan Bishop of the church in Westchester County, were involved in consultations with local Congressman Richard Ottinger about transferring the property to the Department of the Interior for stewardship by the National Park Service.

“It is a historic gem that we can no longer afford to maintain,” Bishop Whetmore said in 1975, when a survey calculated costs for critical maintenance and upgrades on the church at $100,000, or about $427,000 today. “If that means we would no longer be able to use it as a gathering place for a congregation, then we would have to accept it.”

A part time assignment by the 1970s, Rev. John Zacker shepherded the congregation in the final years, conducting an early Sunday morning service before traveling the short distance to lead an additional Episcopal observance at St. John the Divine. Enrolled in law school, Rev. Zacker’s legal training helped facilitate negotiations over the transfer of the property. While recognizing the historical value of the church, he argued that the religious mission needed fulfillment and proposed that the Diocese might combine the two small memberships at St. Paul’s, perhaps sustaining the parish.

But the historical value and operational costs of St. Paul’s conflicted with the fading prospects of salvaging the religious community which worshipped at the church. The six acre property, improved with two buildings, including an 18th century stone edifice, and about 2,500 memorial gravestones, was far more expensive to maintain than other local Episcopal properties. Additionally, St. Paul’s represented sufficient historical value to attract the interest of another controlling party -- the Federal Government. Those compelling circumstances persuaded the Diocese. An agreement to transfer the property, which included immediate funding for emergency repairs, was reached in November 1978.

With the realization that a cession of the church was on the horizon, Rev. Zacker remembered that some of the remaining parishioners had already shifted loyalties to other houses of worship. “Our congregation kind of faded away, since most people saw what was coming,” he recalled. He preached the last regular Sunday service before a small gathering that year, and the remaining congregation merged with St. John the Divine Episcopal Church, (tragically destroyed in a fire in February 1988). To accommodate the church’s utilization for secular activities under the Park Service, St. Paul’s was de-consecrated in November 1980. A few tears were shed, and Ms. Harewood soberly captured the spirit of the final moments: “I would have liked to save it in some other way, but we couldn’t.”

A new chapter in the history of St. Paul’s commenced.