Last updated: August 9, 2020

Article

An 1880 “October Surprise”

www.handwritinganalysis.ca

Last minute tricks have long been a part of presidential politics, going back at least to the 1844 campaign, when James K. Polk was accused of branding his slaves. Most sources date the use of the phrase “October Surprise” either to the election of 1968, when President Lyndon Johnson declared a bombing halt in Vietnam on October 30th, or to Richard Nixon’s Secretary of State who declared, “Peace is at hand” in Vietnam on October 26, 1972. In both cases, the announcements were immediately seen by the press and the public as intending to influence the outcome of the presidential election. Because both were announcements by members of the current administration, just a few days before people voted, it was nearly impossible for the opposing party to respond. Especially when the country is closely divided, October Surprises have the potential to turn elections.

When James A. Garfield ran for president in 1880, tradition dictated that a candidate write a formal letter to the chairman of his party accepting the nomination. The letter addressed the major issues that were most likely to be discussed during the campaign and set out the candidate’s positions and feelings on those topics. The acceptance letter was the only direct communication from the candidate to the electorate; campaigning was done by party regulars directed by state and national party committees. The candidate stayed at home maintaining a dignified silence. Much rested on the content of the acceptance letter, and candidates always took time to prepare it carefully. Garfield was officially notified on June 8, 1880, that he had been nominated at the Republican convention in Chicago. His letter of acceptance was dated July 12, 1880.

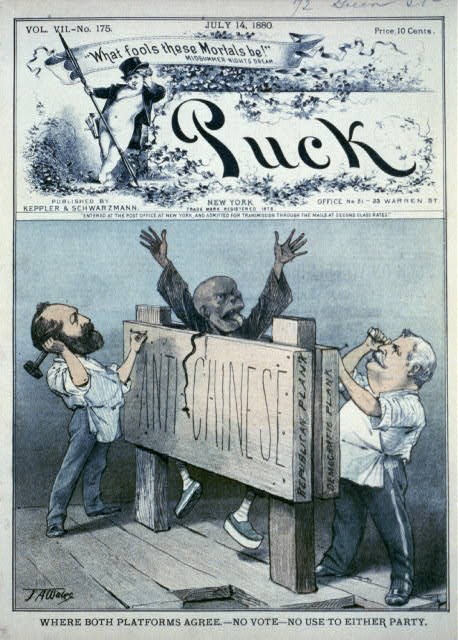

The letter addressed several important issues—civil and voting rights, education, public finance, and internal improvements. These were followed by a very carefully written paragraph on the question of Chinese immigration. 120,000 Chinese, mostly young men and boys, had come to the United States during the 1870s. Almost all of them came as contract workers for the railroads, who paid them just pennies a day to do some of the most dangerous tasks involved in the construction of transcontinental rail lines. Especially in the west, these immigrants were seen as a threat to American labor. In his acceptance letter Garfield said that the contract system used to bring in Chinese labor was “too much like an importation to be welcomed without restriction…” He encouraged negotiation with the Chinese government to “prevent the evils likely to arise from the present situation.” And if negotiations failed, “[I]t will be the duty of Congress to mitigate the evils already felt, and prevent their increase, by such restrictions as, without violence or injustice, will place upon a sure foundation the peace of our communities and the freedom and dignity of labor.”

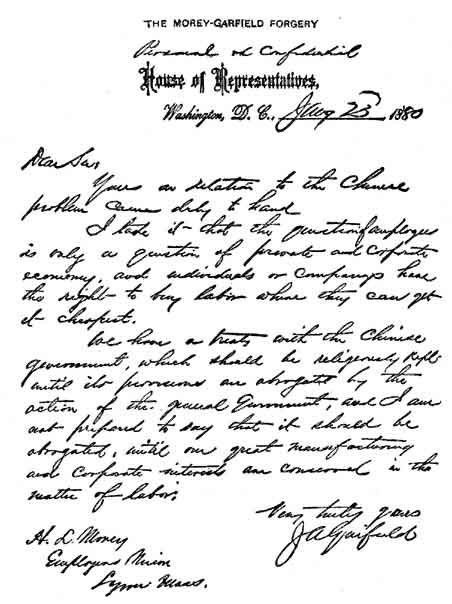

The question of Chinese immigration did not come up again until October 20. Garfield received a telegram that day asking about a letter the congressman had supposedly written on “the Chinese question.” Within hours he was sent the text of the letter. Written on House of Representatives stationery and dated January 23, 1880, it was addressed to an H. L. Morey of the Employers Union in Lynn, Massachusetts. In the letter, Garfield allegedly said that “individuals and companys [sic] have the right to buy labor where they can get it cheapest.” Further, the letter says that the treaty with China should remain in effect “until our great manufacturing and corporate interests are conserved in the matter of labor.” Garfield immediately denied that he had written it.

www.handwritinganalysis.ca

A New York newspaper called Truth published the letter the next day, saying that a friend of the Republican candidate—a prominent Democrat—had confirmed that the handwriting was Garfield’s. Democrats pounced, printing and circulating half a million copies. Letters were nailed to signposts and pasted on store windows. Thousands were sent to every town in California, where Chinese labor was the central issue of the campaign. The letter could also be a threat in working class neighborhoods in eastern industrial cities and towns. Some called it “Garfield’s death warrant.”

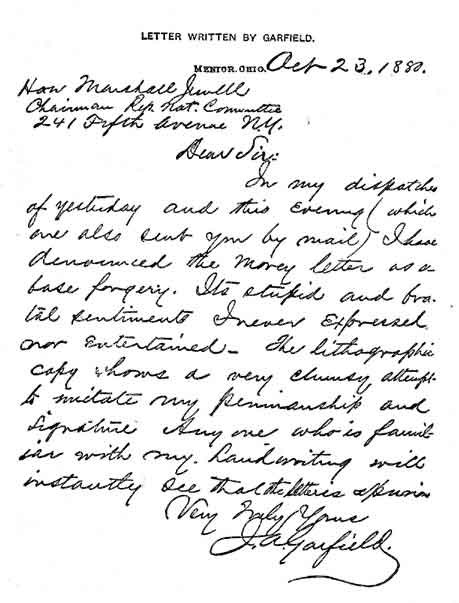

The Republican National Committee sent detectives to Lynn, Massachusetts where they could find no trace of a person named H. L. Morey, or of the Employers Union. Garfield meanwhile asked to see a photo reproduction of the letter, and he sent a secretary to Washington to comb his files for any correspondence from Morey or the Employers Union. Nothing was found in the files, and after seeing a facsimile of the Morey letter, Garfield finally felt able to denounce it as a “manifestly bungling attempt to copy my hand and signature.” He authorized the Republican National Committee to reproduce and distribute the letter he had sent days before, denying its authenticity. Nearly a week went by before Garfield’s handwritten response was published in newspapers, often side by side with the Morey forgery. Democrats used the delay as evidence of Garfield’s guilt, but given the visual evidence before them, most voters concluded that the Morey letter was “a stupid forgery.”

Library of Congress

-Joan Kapsch, Park Guide, James A. Garfield National Historic Site, October 2012 for the Garfield Observer.