Last updated: March 30, 2021

Article

Amphibious Assault on Fort Sumter

Library of Congress

By the spring of 1863, the Confederacy had occupied Fort Sumter for two years. On April 7, 1863, a fleet of nine US navy vessels steamed into the mouth of the harbor and opened fire on Fort Sumter and Fort Moultrie. Following the engagement, the Confederates and their enslaved laborers immediately got to work strengthening Fort Sumter in anticipation of further attacks.

They did not have long to wait. Three months later, on July 10, Union forces assaulted the southern end of Morris Island, a sea coast island on the southern side of Charleston Harbor. Heavy fighting ensued until Confederate forces withdrew from Batteries Wagner and Gregg (located on the northern end of the island) on the night of September 6-7. Prior to that withdrawal, Union heavy Parrott rifles had opened fire on Fort Sumter from the southern part of Morris Island on August 17, thus beginning the longest siege under fire in US military history.

Wikimedia Commons

Preparations for the Amphibious Assault

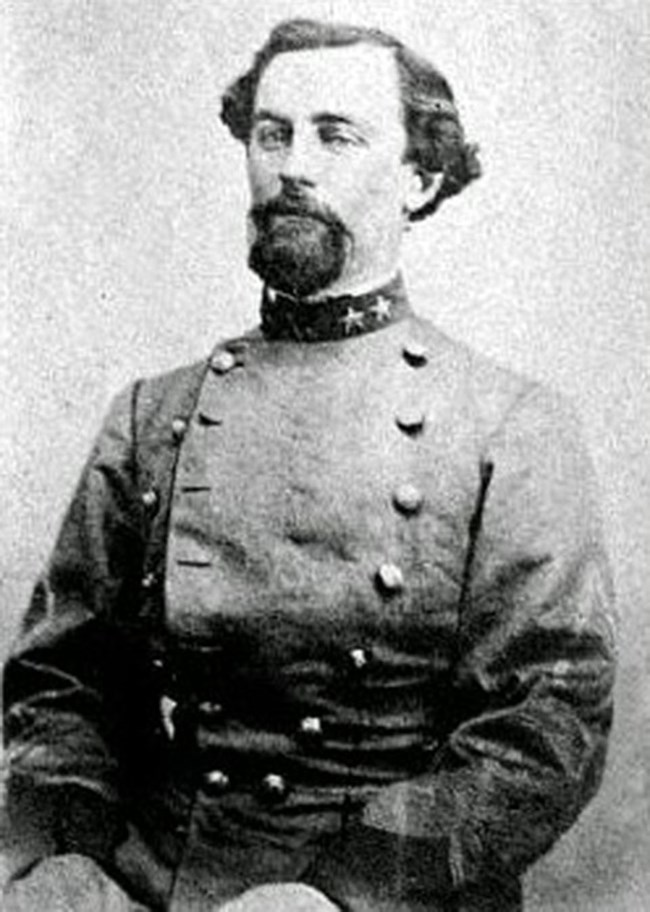

Union Rear Admiral John A. Dahlgren, commander of the blockade squadron, wasted no time. The next morning, September 7th, he sent a message to Fort Sumter demanding its surrender. Major Stephen Elliott, who had taken command of the fort only two days before, checked with his superior, Brigadier General P.G.T. Beauregard, and then replied, “Inform Admiral Dahlgren that he may have Fort Sumter when he can take it and hold it.”

Upon receiving this reply, Dahlgren immediately ordered an amphibious assault on the fort to take place on the night of 8-9 September. Also on the morning of the 7th, he sent the ironclad USS Weehawken to probe Confederate obstacles between Sumter and the inner harbor defenses. During an exchange of fire with Confederate batteries, the Weehawken ran aground and didn’t escape until the next day. Meanwhile, the Union Army led by Brigadier General Quincy A. Gillmore on Morris Island was also planning to assault Fort Sumter that very same night of September 8 despite no planned cooperation between the two attacks.

Dahlgren assigned Commander Thomas H. Stevens from the ironclad USS Patapsco to lead the amphibious assault. Stevens learned of his assignment only a few hours before it was to begin. In a meeting with Dahlgren, Stevens opposed the attack as having insufficient time to prepare, no provision for scaling ladders, the gathering of small boats in full view of the enemy, and an inability to hold the fort once it was taken. Dahlgren told him that he only needed to take the fort and would find nothing but a corporal’s guard to oppose him.

Library of Congress

At Fort Sumter, Elliott was quite aware of the impending attack. The probe by the Weehawken and the assembly of small boats around the Union flagship were major clues reinforced by intercepted signals between Union vessels decoded with a signal book captured by the Confederates back in April unbeknownst to the US Navy. Thus preparations to meet the attack were thorough and extensive.

While the walls at Sumter had suffered considerable damage by the Union bombardments, it remained a formidable defensive work. Instead of sloping gradually from the parapet to the water’s edge, debris from the bombardment of the gorge wall sloped only from the parapet to the top of a 12-foot high sandbag barricade, piled up to protect the wall from Union breaching battery fire. Without the aid of scaling ladders, an attacker could not possibly reach the top of the wall. In addition, breaches in the sea wall, which appeared from a distance to offer easy access to the fort, were actually filled with 20 feet of sand.

The fort was garrisoned by 320 infantrymen of Major Julius A. Blake’s Charleston Battalion. They were armed with rifled muskets, hand grenades, and fire-balls, known as “Greek Fire.” In addition, Confederate batteries on James and Sullivan’s Islands and the guns of the Confederate ironclad, CSS Chicora, were pre-aimed to drop shells around the outer perimeter of Sumter’s walls at the water’s edge upon a signal from Elliott.

The Assault

Commander Steven’s assault force of 100 Marines and 350 sailors rowed across the water towards Fort Sumter with hopes of victory. The sailors were armed only with pistols and cutlasses while the Marines were armed with carbines. One division was to create a diversion by attacking the northwest or right face wall while the other four divisions launched the main attack a short time later against the opposite southeast face or gorge wall.

Inside the fort, Major Elliott and the Confederates manning the parapet and the loopholes of the second tier watched the Union boats approach holding their fire until the first boats began to land. A Confederate sentry hailed them loudly but received no reply. A few seconds later, a red signal rocket was fired by Elliott from Sumter, and the fighting began.

Instead of waiting for the diversionary attack to take hold, boats in the main attack force forged ahead. As the first few boats landed amidst the debris at the base of the walls, they were met with volleys of rifle fire, hand grenades, fire balls, and bricks tossed from the debris. At the same time, exploding shells rained down from the Confederate shore batteries along with fire from the ironclad Chicora. Those who managed to debark from their boats briefly tried to return fire but soon sought shelter among the debris at the base of the walls. Following boats were unable to land due to the heavy fire and soon turned away, leaving sailors and Marines stranded with no choice but to surrender. The battle was over in twenty minutes.

The Aftermath

Union losses were 6 killed, 2 officers and 17 men wounded, and 10 officers (including Lieutenant Commander E.P. Williams, second in command of the assault force) and 92 men captured for a total of 127 casualties. Five boats were also captured. The Confederates suffered no casualties. Union dead were shipped back to the fleet while the wounded and captured were removed to the city the following day.

Much finger pointing followed the debacle on the Union side for several months. However, Admiral Dahlgren managed to keep his job. Cooperation between Dahlgren and Gillmore remained rocky. On the Confederate side, General Beauregard sent a congratulatory note to Major Elliott calling the repulse “a brilliant success.” Major Blake’s Charleston battalion was also commended.

The effects of the failed amphibious assault were significant and lasting. Never again was Fort Sumter subjected to a direct assault by troops. By the end of September, however, Union guns on Morris Island had resumed the bombardment that would continue off and on for the next 17 months until the Confederates evacuated Fort Sumter and the Charleston defenses on the night of February 17, 1865, thus ending the longest siege under fire in US military history to date.