Last updated: August 7, 2025

Article

Climate and Water Monitoring at Amistad National Recreation Area: Water Year 2023

NPS

Overview

Together, climate and hydrology shape ecosystems and the services they provide, particularly in arid and semi-arid ecosystems. Understanding changes in climate, groundwater, and surface water is key to assessing the condition of park natural resources—and often, cultural resources.

At Amistad National Recreation Area (Figure 1), Chihuahuan Desert Inventory and Monitoring Network scientists study how ecosystems may be changing by taking measurements of key resources, or “vital signs,” year after year—much as a doctor keeps track of a patient’s vital signs. This long-term ecological monitoring provides early warning of potential problems, allowing managers to mitigate them before they become worse. At Amistad National Recreation Area, we monitor climate, groundwater, reservoir level, and springs, among other vital signs.

Surface water and groundwater conditions are closely related to climate conditions. Because they are better understood together, we report on climate in conjunction with water resources. Reporting is by water year (WY), which begins in October of the previous calendar year and goes through September of the water year (e.g., WY2023 runs from October 2022 through September 2023). This web report presents the results of climate and water monitoring at Amistad National Recreation Area in WY2023.

NPS

Climate and Weather

There is often confusion over the terms “weather” and “climate.” In short, weather describes instantaneous meteorological conditions (e.g., it’s currently raining or snowing, it’s a hot or frigid day), and climate reflects patterns of weather at a given place over longer periods of time (seasons to years). Climate is the primary driver of ecological processes on Earth. Climate and weather information provide context for understanding the status or condition of other park resources.

Methods

A National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Cooperative Observer Program (NOAA COOP) weather station (Amistad Dam #410225) has been operational at Amistad National Recreation Area since 1964 (Figure 1). This station provides a reliable, long-term climate dataset for analyses in this climate and water report. Data from this station are accessible through Climate Analyzer.

NPS

Results

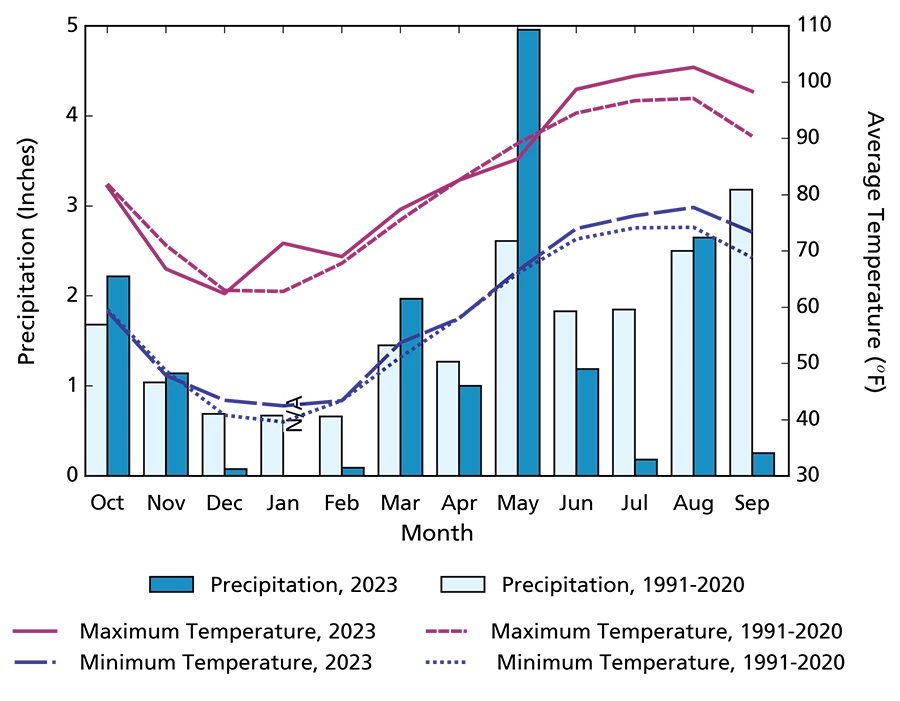

Precipitation

Annual precipitation at Amistad Dam in WY2023 was 15.83″ (40.2 cm), 3.60″ (9.1 cm) less than the 1991–2020 annual average. Annual precipitation may be slightly underestimated because of 5 days of missing data in January. May received nearly twice the 1991–2020 average precipitation (Figure 2). Precipitation totals in October, November, March, and August were also above average. Substantially less precipitation occurred during December, February, July, and September, each receiving 8–14% of the 1991–2020 averages. Extreme daily rainfall events (≥ 1.00″; 2.54 cm) occurred on 6 days in WY2023 (Table 1), one more than the average annual frequency of 5.1 days.

| Date | Rainfall (in) | Rainfall (cm) |

|---|---|---|

| 17 October 2022 | 1.30 | 3.3 |

| 13 May 2023 | 2.02 | 5.1 |

| 16 May 2023 | 1.35 | 3.4 |

| 28 May 2023 | 1.32 | 3.4 |

| 08 June 2023 | 1.09 | 2.8 |

| 23 August 2023 | 2.23 | 5.7 |

Air Temperature

The mean annual maximum temperature at Amistad National Recreation Area in WY2023 was 83.4°F (28.5°C), 2.3°F (1.3°C) above the 1991–2020 average. The mean annual minimum temperature in WY2023 was 60.0°F (15.5°C), 1.9°F (1.1°C) above the 1991–2020 average. Mean monthly maximum and minimum temperatures in WY2023 differed by as much as 8.6°F (4.8°C; see January as an example) relative to the 1991–2020 monthly averages (Figure 2). Mean monthly maximum and minimum temperatures were variable relative to the 1991–2020 averages during the first part of the year (October–April). Temperatures from June through September were warmer than the 1991–2020 averages. Extremely hot temperatures (≥ 102.0°F; 38.9°C) occurred on 57 days in WY2023, over two and a half times the average frequency of 21.5 days. Extremely cold temperatures (≤ 35.0°F; 1.7°C) occurred on 17 days, slightly less than the average frequency of 20.1 days.

NPS

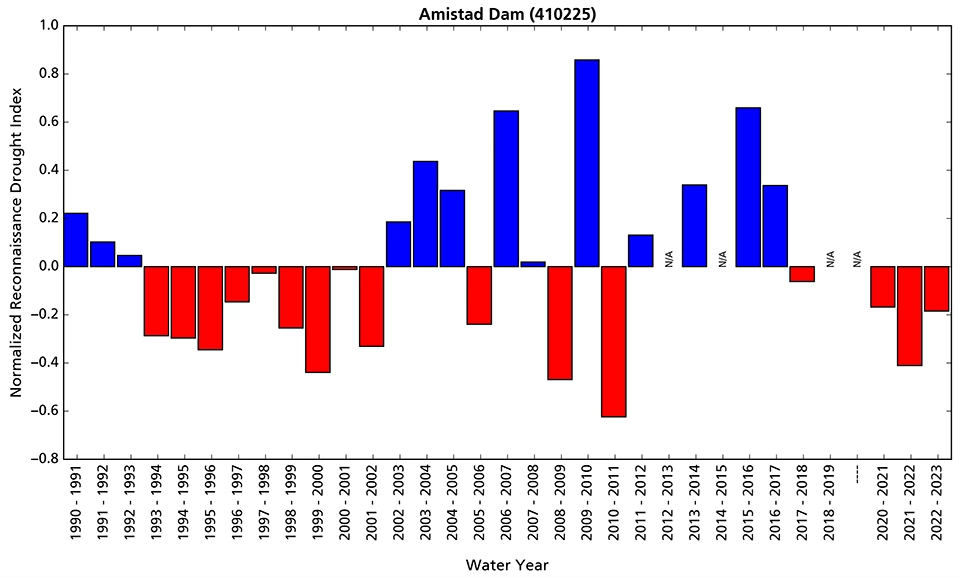

Drought

Reconnaissance drought index (Tsakiris and Vangelis 2005) provides a measure of drought severity and extent relative to the long-term climate. It is based on the ratio of average precipitation to average potential evapotranspiration (the amount of water loss that would occur from evaporation and plant transpiration if the water supply was unlimited) over short periods of time (seasons to years). The reconnaissance drought index for Amistad National Recreation Area indicates that WY2023 was drier than the 1991–2023 average for the third consectutive year from the perspective of both precipitation and potential evapotranspiration (Figure 3).

Reference: Tsakiris G., and H. Vangelis. 2005. Establishing a drought index incorporating evapotranspiration. European Water 9: 3–11.

NPS

NPS

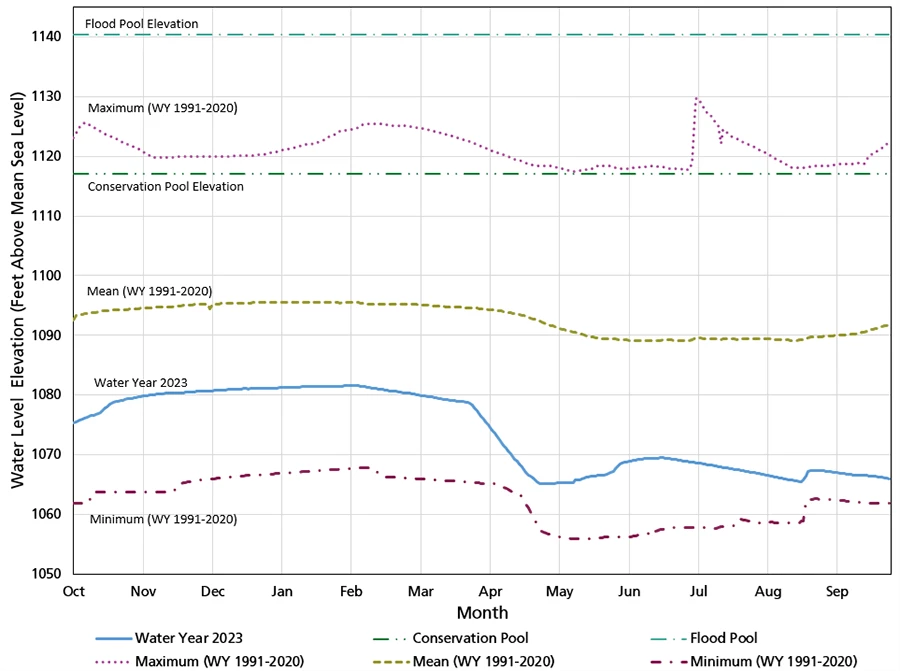

Reservoir Level

The Amistad International Reservoir was formed by the construction of Amistad Dam between 1964 and 1969. Reservoir level is not a Chihuahuan Desert Network vital sign; however, it is included in this report because the reservoir level has implications for park resources throughout Amistad National Recreation Area, including groundwater and springs.

Methods

The International Boundary and Water Commission (IBWC) has operated a water level gage at Amistad Reservoir (International Amistad Reservoir Storage Station Number 08-4508.00) since 1968 when filling began. The gage is located at the downstream end of the reservoir. Every 15 minutes, the gage collects water level data, which are available from the IBWC and the Texas Water Development Board (TWDB).

Recent Findings

In WY2023, mean reservoir level was 1,073.90 feet above mean sea level (ft amsl; 327.32 m amsl) with a range of 1,065.21 to 1,081.57 ft amsl (324.68 to 329.66 m amsl; Figure 4). During the entire year, reservoir level remained below the flood pool elevation of 1,140.4 ft amsl (347.59 m amsl; elevation of flood gates and emergency spillway) and the conservation pool elevation of 1,117.0 ft amsl (340.46 m amsl; maximum normal operating level, above which the storage is used to regulate floodwaters). Daily reservoir water level in WY2023 was on average 43.10 ft (13.14 m) below the conservation pool. Throughout the year, the reservoir ranged from 32–47% full. Throughout WY2023, the daily mean reservoir level was between the daily 1991–2020 average and minimum.

NPS

Groundwater

Groundwater is one of the most critical natural resources of the American Southwest. It provides drinking water, irrigates crops, and sustains rivers, streams, and springs throughout the region.

Methods

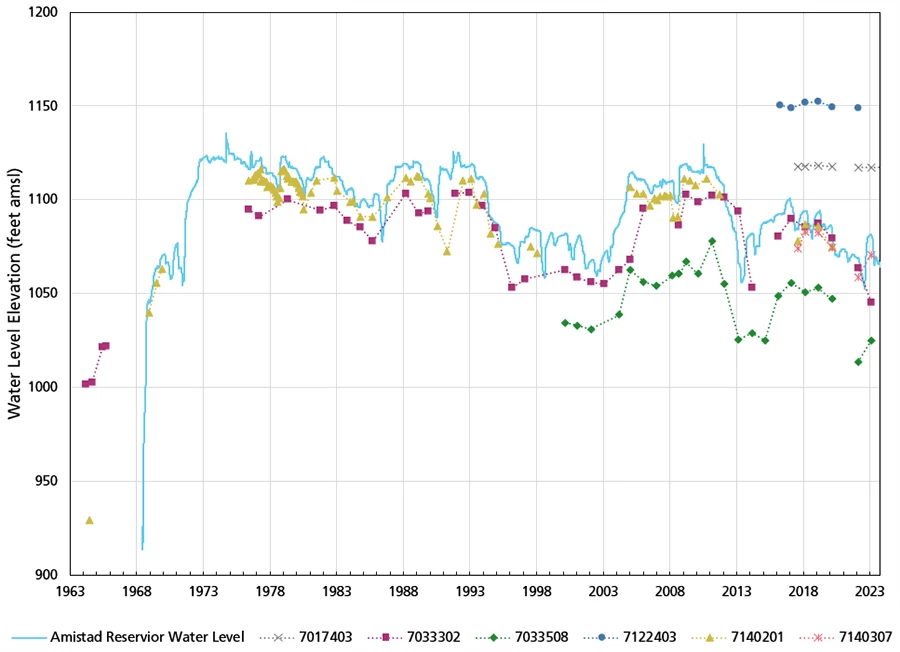

Amistad National Recreation Area groundwater is monitored using six wells in or near the recreation area (Figure 1). Each well is monitored annually by the Texas Water Development Board (TWDB) and the data are available at the TWDB Database.

Results

Two wells could not be measured in WY2023: well 7122403 was not measured because we were unable to access the well site, and well 7140201 was not measured because of a possible well collapse. The other four wells were monitored in February. WY2023 groundwater levels increased in two wells compared to WY2022 measurements: wells 7033508 and 7140307. Both wells are near the south edge of the reservoir (Table 2, Figure 5). These results are consistent with a 12.46 ft (3.80 m) increase in reservoir level when groundwater was sampled in WY2023 compared to WY2022. Groundwater level in well 7017403 in WY2023 was nearly the same as the previous year, only 0.01 ft (0.003 m) lower. Well 7017403 is substantially higher than the reservoir level because it is up gradient of the reservoir, adjacent to the Devils River. Well 7033302 was the only well to show a large decrease from the previous year—a decrease of 18.83 ft (5.74 m). The cause of this drop is unclear, but nearby pumping could be responsible.

| State Well Number | Location | Wellhead Elevation (ft amsl) |

Depth to Water (ft bgs) |

Water Level Elevation (ft amsl) |

Change in Elevation from WY2022 (± ft) | Elevation Difference from Amistad Reservoir Level (± ft) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7017403 | 15.6 mi NNE of Amistad Dam on Devil's River | 1,180 | 62.59 | 1,117.41 | −0.01 | +35.98 |

| 7033302 | 9.2 mi ENE of Amistad Dam | 1,215 | 169.80 | 1,045.20 | −18.83 | −36.14 |

| 7033508 | 6.7 mi E of Amistad Dam | 1,175 | 149.71 | 1,025.29 | +11.64 | −56.05 |

| 7122403 | 25.3 mi NW of Amistad Dam on Pecos River | 1,312 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 7140201 | 3.2 mi NNE of Amistad Dam | 1,167 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 7140307 | 2.0 mi NE of Amistad Dam | 1,162 | 91.06 | 1,070.94 | +12.14 | −10.40 |

NPS

Springs

Background

Springs, seeps, and tinajas (discrete pools in a rock basin or impoundments in bedrock) are small, relatively rare biodiversity hotspots in arid lands. They are the primary connection between groundwater and surface water and are important water sources for plants and animals. For springs, the most important questions we ask are about persistence (How long was there water in the spring?) and water quantity (How much water was in the spring?). Springs reporting is by water year (WY), which begins in October of the previous calendar year and goes through September of the current calendar year (e.g., WY2023 runs from October 2022 through September 2023). WY2023 springs sampling at Amistad National Recreation Area occurred between 30 March and 03 April 2023. Water persistence is monitored continuously throughout the water year, but in this report we only present WY2023 persistence data up to the springs sampling visit date.

Methods

Chihuahuan Desert Network springs monitoring is organized into the four modules described below.

Site Characterization

This module provides context for interpreting change in the other modules. We record GPS locations, draw a site diagram, and describe the spring type (e.g., helocrene, limnocrene, rheocrene, or tinaja) and its associated vegetation in this module. Helocrene springs emerge as low-gradient wetlands, limnocrene springs emerge as pools, and rheocrene springs emerge as flowing streams. This module is completed once every five years or after significant events.

Site Condition

We estimate the level of natural and anthropogenic disturbances and the level of stress on vegetation and soils at the spring on a scale of 1–4, where 1 = undisturbed, 2 = slightly disturbed, 3 = moderately disturbed, and 4 = highly disturbed. Types of natural disturbances can include flooding, drying, fire, wildlife impacts, windthrow of trees and shrubs, beaver activity, and insect infestations. Anthropogenic disturbances can include roads, off-highway vehicle trails, hiking trails, livestock and feral-animal impacts, removal of invasive non-native plants, flow modification, and other evidence of human use of the spring site. We take repeat photographs from the same location and perspective to show the spring and its landscape context. We note the presence of certain obligate wetland plant species (plant species that almost always occur only in wetlands), facultative wetland plant species (plant species that usually occur in wetlands but also occur in other habitats), and invasive non-native bullfrogs (American bullfrog [Lithobates catesbeianus]). We also record the density of invasive non-native plants using a qualitative scale (1–5 plants, scattered patches, evenly distributed patches, or a matrix).

Water Quantity

We measure the persistence of surface water, amount of spring discharge, and wetted extent (area that contained water). To estimate persistence, we analyze the variance of temperature measurements taken by logging thermometers placed at or near the orifice (spring opening). Because water mediates variation in diurnal temperatures, data from a submerged sensor will show less daily variation than data from an exposed, open-air sensor; this tells us when the spring was wet or dry. Surface discharge is measured with a timed sample of water volume. Wetted extent is a systematic measurement of the physical length (up to 100 m), width, and depth of surface water. It is assessed using a technique for either standing water (e.g., limnocrene and helocrene springs) or flowing water (e.g., rheocrene springs).

Water Quality

We measure core water quality and water chemistry parameters. Core water quality parameters include water temperature, pH, specific conductivity (a measure of dissolved compounds and contaminants), dissolved oxygen (how much oxygen is present in the water), and total dissolved solids (an indicator of potentially undesirable compounds). Discrete measurements of these parameters are collected with a multiparameter meter. If the meter fails calibration check(s), we do not present data. Water chemistry is assessed by collecting surface water sample(s) and estimating the concentration of major ions with a photometer in the field. These parameters are collected at one or more sampling locations within a spring. Data are presented only for the primary sampling location within each spring. Each perennial spring is somewhat unique, and Texas has not adopted water quality standards that would apply across the diversity of springs described here. Ongoing, long-term data collection at each spring will improve our understanding of the natural range in water quality and water chemistry parameters for a given site.

List of Springs

Scroll down or click on a spring below to view monitoring results.

Big Satan Canyon Spring ǀ Dead Man's Canyon Spring ǀ Indian Springs Canyon Spring ǀ Mouth of the Pecos Spring

NPS

Big Satan Canyon Spring

Big Satan Canyon Spring (Figure 6) is a rheocrene spring (a spring that emerges into one or more stream channels) located in Big Satan Canyon, a tributary to the Devil’s River. The spring emerges from multiple orifices created by small fissures in the bedrock-lined canyon and forms an elongated pool that has measured up to 32.5 m (106.6 ft) in length and is bounded on three sides by rock. The WY2023 visit occurred on 02 April 2023, and the spring was wetted (contained water). We did not collect data at Big Satan Canyon Spring in WY2022 because of logistical and time constraints.

Site Condition

In WY2023, we rated Big Satan Canyon Spring as slightly disturbed by drying because there were upland plant species in the vicinity of the springbrook (rated undisturbed to slightly disturbed in the past) and moderately disturbed by wildlife because of the presence of abundant droppings and evidence of grazing (rated undisturbed to slightly disturbed in the past). No other natural or human-caused disturbances were observed at Big Satan Canyon Spring in WY2023.

We did not observe the invasive non-native American bullfrog (Lithobates catesbeianus) at Big Satan Canyon Spring in WY2023. We observed five species of invasive non-native plants at the spring: scattered patches of giant reed (Arundo donax, not previously observed); a matrix of yellow bluestem (Bothriochloa ischaemum, scattered patches to evenly distributed patches found in 2018–2021); scattered patches of tree tobacco (Nicotiana glauca, 1–5 plants to scattered patches observed in 2017–2021); 1–5 sowthistle plants (Sonchus sp., not previously observed); and 1–5 lilac chastetree plants (Vitex agnus-castus, not previously observed).

We observed eight species of obligate/facultative wetland plants in WY2023: bluestem (Andropogon sp., a grass previously observed in 2019–2021); bulrush (Schoenoplectus sp., a sedge not previously observed); common buttonbush (Cephalanthus occidentalis, a shrub not previously observed); fogfruit (Phyla sp., a forb observed in 2018–2021); giant reed (Arundo donax; an invasive non-native grass not previously observed); mule-fat (Baccharis salicifolia, a shrub observed in 2021); rushes (Juncaceae, observed in 2018–2021); and spikerush (Eleocharis sp., a sedge observed in 2018–2021).

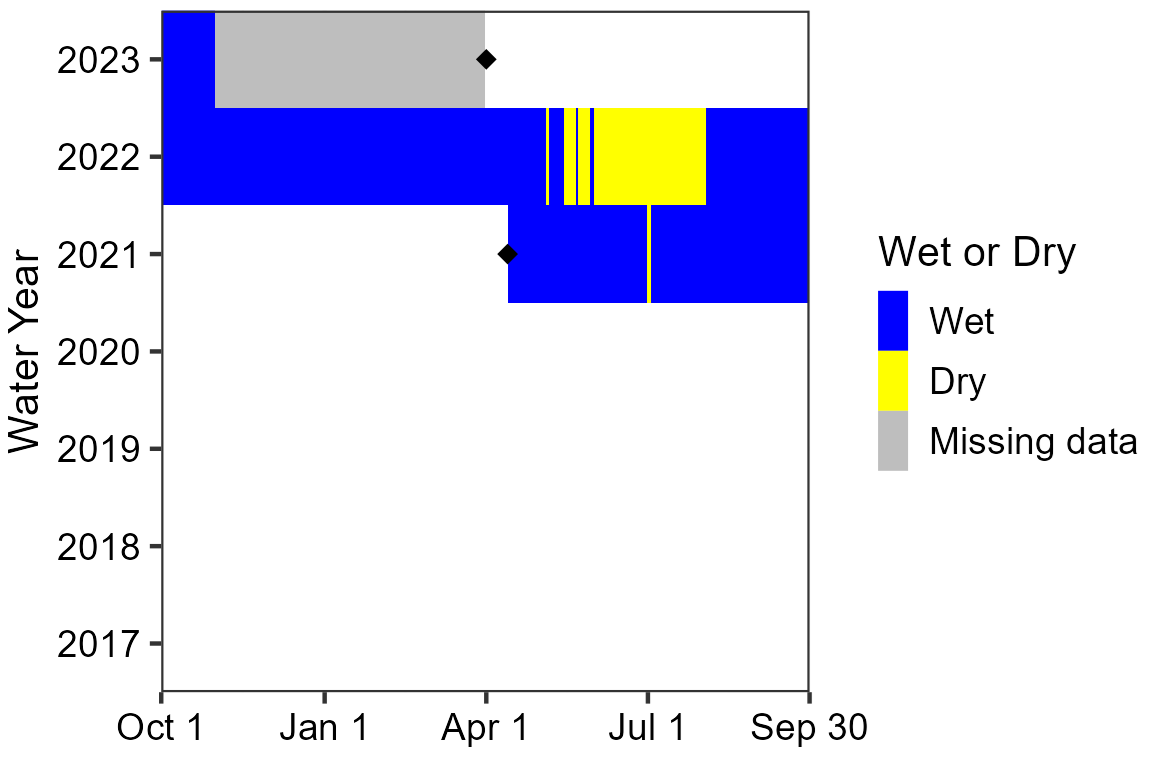

Water Quantity

Sensors are deployed and data are downloaded during our annual visit, which takes place in the middle of the water year; the dates of these visits are indicated by black diamonds in the persistence graph (Figure 7). A sensor malfunction resulted in only 31 days of measurements up to the WY2023 spring visit on 02 April 2023. The temperature sensor indicated that Big Satan Canyon Spring was wetted for 31 of 31 days (100%) measured. In prior water years, the spring was wetted 78.4–98.8% of the days measured across entire water years.

NPS

Discharge measurements were last conducted at Big Satan Canyon Spring in WY2017, when discharge was estimated at 12.1 L/min (3.2 gal/min; Table 3). Since then, discharge has not been measurable at the site.

Wetted extent (a measure of length, width, and depth of surface water) was most recently assessed in WY2018 (Table 4), when the total brook length was 32.5 m (106.6 ft) and width averaged 11.4 m (37.4 ft). Depth measurements are not taken at Big Satan Canyon Spring because of safety and access concerns. We are evaluating alternative methods, such as GPS mapping, to systematically assess the wetted extent at this spring in the future.

Water Quality

Core water quality (Table 5) and water chemistry (Table 6) data were collected at the primary sampling location at the most upstream edge of the spring in WY2023. Levels of dissolved oxygen, specific conductivity, total dissolved solids, and pH were within the ranges of values previously recorded (2017–2021), while temperature was slightly lower. Alkalinity was within the range of past measurements. Calcium was higher than in the past, and chloride, magnesium, potassium, and sulphate were below prior measurements (2017–2018).

Big Satan Canyon Spring Data Tables

| Sampling Location | WY2023 Mean (range of prior means) |

Prior Years Measured (# of visits with measurements) |

|---|---|---|

| 002 | c.n.s. (12.1) | 2017 (1) |

| Measurement | WY2023 Value (range of prior values/means) |

Prior Years Measured (# of visits with measurements) |

|---|---|---|

| Width (m) | c.n.s. (11.4) | 2018 (1) |

| Depth (cm) | c.n.s. (c.n.s.) | 2018 (1) |

| Length (m) | c.n.s. (32.5) | 2018 (1) |

| Sampling Location | Measurement Location | Parameter | WY2023 Value (range of prior values) |

Prior Years Measured (# of measurements) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 003 | Center | Dissolved oxygen (mg/L) | 5.69 (4.67–5.71) |

2018–2021 (3) |

| 003 | Center | pH | 7.25 (7.23–7.36) |

2017–2021 (4) |

| 003 | Center | Specific conductivity (µS/cm) | 462.3 (431.2–463.2) |

2018–2021 (3) |

| 003 | Center | Temperature (°C) | 22.3 (22.6–23.4) |

2017–2021 (6) |

| 003 | Center | Total dissolved solids (mg/L) | 300 (273–301) |

2017–2021 (4) |

| Sampling Location | Measurement Location | Parameter | WY2023 Value (range of prior values) |

Prior Years Measured (# of measurements) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 003 | Center | Alkalinity (CaCO3) |

195 (190–240) |

2017–2018 (2) |

| 003 | Center | Calcium (Ca) |

68 (64) |

2017–2018 (2) |

| 003 | Center | Chloride (Cl) |

0 (8–15) |

2017–2018 (2) |

| 003 | Center | Magnesium (Mg) |

7 (13–15) |

2017–2018 (2) |

| 003 | Center | Potassium (K) |

0.0 (0.7–1.6) |

2017–2018 (2) |

| 003 | Center | Sulphate (SO4) |

0 (2) |

2017–2018 (2) |

NPS

Dead Man's Canyon Spring

Dead Man’s Canyon Spring (Figure 8) is a hanging garden spring (a complex, multi-habitat spring that emerges along geologic contacts and seeps onto underlying walls). The spring is situated in Dead Man’s Canyon, a tributary of the Pecos River, where water seeps from the cliff face, trickling down the rocks and supporting a robust community of wetland plants clinging to the wall (Figure 9). Hidden grottos hold water and create pools behind the vegetation. The flow from this hanging garden converges with water from two other orifices inside the canyon bottom to form a channel that has extended over 100 m. The WY2023 visit occurred on 01 April 2023, and the spring was wetted (contained water).

Site Condition

In WY2023, we rated Dead Man’s Canyon Spring slightly disturbed by contemporary human use because of small amounts of trash in the immediate area (rated undisturbed to slightly disturbed in the past) and slightly disturbed by wildlife, with signs of browsing and droppings throughout the site (rated undisturbed to slightly disturbed in the past). No other natural or human-caused disturbances were observed at Dead Man’s Canyon Spring in WY2023.

We did not observe any invasive non-native American bullfrogs (Lithobates catesbeianus) at Dead Man’s Canyon Spring in WY2023. We observed four species of invasive non-native plants: evenly distributed patches of giant reed (Arundo donax; scattered patches observed in 2019–2022); scattered patches of yellow bluestem (Bothriochloa ischaemum; scattered patches observed in 2018–2019); 1–2 red brome plants (Bromus rubens; not previously observed); and scattered patches of Bermudagrass (Cynodon dactylon; scattered patches observed in 2017–2019).

We observed five species of obligate/facultative wetland plants at Dead Man’s Canyon Spring in WY2023: bulrush (Schoenoplectus sp., a sedge not previously observed); common buttonbush (Cephalanthus occidentalis, a shrub observed in 2019); giant reed (Arundo donax, a grass observed in 2018–2022); maidenhair fern (Adiantum sp., a fern observed in 2018–2022); and mule-fat (Baccharis salicifolia, a shrub observed in 2017–2019).

NPS

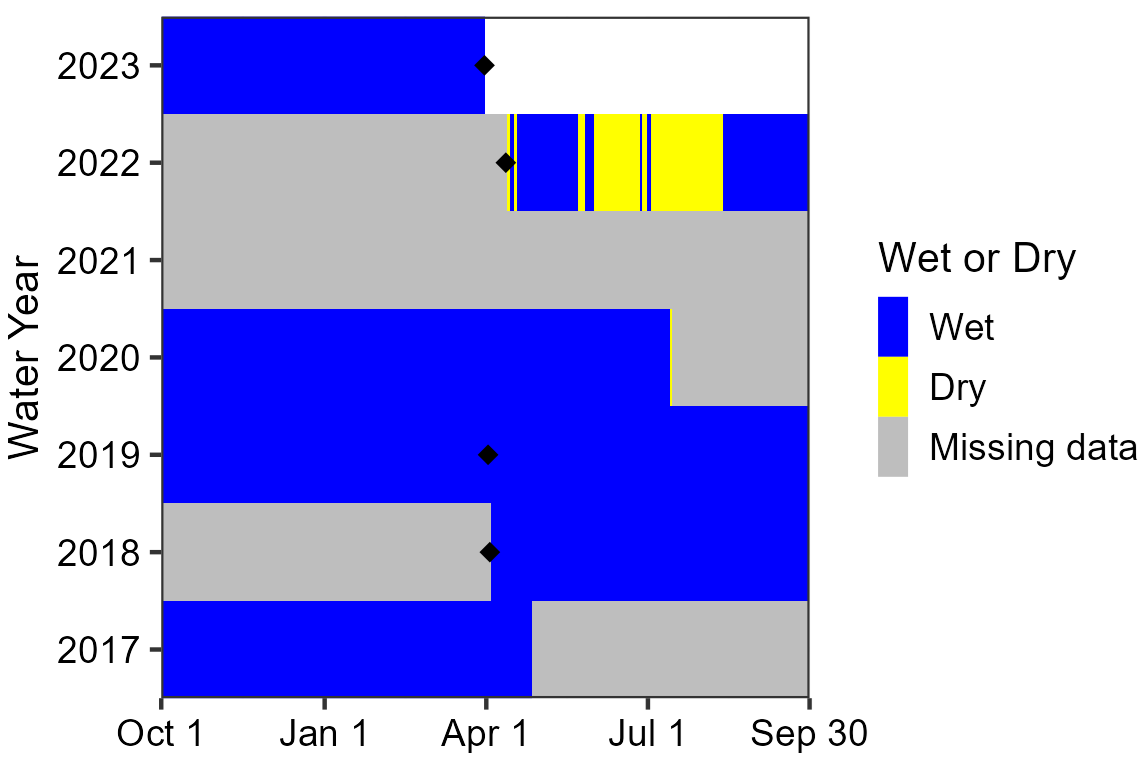

Water Quantity

Sensors are deployed and data are downloaded during our annual visit, which takes place in the middle of the water year; the dates of these visits are indicated by black diamonds in the persistence graph (Figure 10). The temperature sensor indicated that Dead Man’s Canyon Spring was wetted for 183 of 183 days (100%) measured up to the WY2023 visit. In prior water years, the spring was wetted 54.1–100% of the days measured across entire water years.

NPS

In WY2023, the estimated volumetric discharge was 4.3 ± 0.1 L/min (1.1 ± 0.03 gal/min), which falls within the historical range of 1.3 to 14.0 L/min at this sampling location where the flow converges below the hanging garden (2017–2022; Table 7).

Wetted extent was evaluated using a method for flowing water. In WY2023, the total springbrook length exceeded 100 m—the estimated total length was between 200–500 m (656–1,640 ft). In previous assessments, measured springbrook length ranged from 6.7 m (22.0 ft) to 31.8 m (104.3 ft). Width and depth within the first 100 m of springbrook length averaged 496.7 cm (195.6 in) and 10.5 cm (4.1 in), respectively (Table 8). Overall, the increases in length, width, and depth all greatly exceeded previous measurements, doubling (or more than doubling) past observations.

Water Quality

Core water quality (Table 9) and water chemistry (Table 10) data were collected at the primary sampling location, a pool at the base of the hanging garden. In WY2023, levels of dissolved oxygen, specific conductivity, and total dissolved solids were within previous value ranges (2017–2022), while water temperature was below and pH was slightly above past values. Calcium, magnesium, potassium, and sulphate values were consistent with prior years, while alkalinity was below and chloride was above previous measurements.

Dead Man's Canyon Spring Data Tables

| Sampling Location | WY2023 Mean (range of prior means) |

Prior Years Measured (# of visits with measurements) |

|---|---|---|

| 007 | 4.3 ± 0.1 (1.3–14.0) | 2017–2022 (4) |

| Measurement | WY2023 Value (range of prior values/means) |

Prior Years Measured (# of visits with measurements) |

|---|---|---|

| Width (cm) | 496.7 ± 520.3 (85.8–93.0) | 2018–2022 (3) |

| Depth (cm) | 10.5 ± 14.8 (5.2–8.3) | 2018–2022 (3) |

| Length (m) | 100.0 (6.7–31.8) | 2018–2022 (3) |

| Sampling Location | Measurement Location | Parameter | WY2023 Value (range of prior values) |

Prior Years Measured (# of measurements) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 001 | Center | Dissolved oxygen (mg/L) | 8.72 (5.59–12.02) |

2017–2022 (4) |

| 001 | Center | pH | 8.19 (7.84–8.18) |

2017–2022 (4) |

| 001 | Center | Specific conductivity (µS/cm) | 431.5 (424.6–450.8) |

2018–2022 (3) |

| 001 | Center | Temperature (°C) | 18.0 (20.3–22.3) |

2017–2022 (6) |

| 001 | Center | Total dissolved solids (mg/L) | 280 (271–293) |

2017–2022 (4) |

| Sampling Location | Measurement Location | Parameter | WY2023 Value (range of prior values) |

Prior Years Measured (# of measurements) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 001 | Center | Alkalinity (CaCO3) |

160 (180–190) |

2017–2022 (4) |

| 001 | Center | Calcium (Ca) |

56 (56–70) |

2017–2022 (4) |

| 001 | Center | Chloride (Cl) |

36 (13–20) |

2017–2022 (4) |

| 001 | Center | Magnesium (Mg) |

17 (12–96) |

2017–2022 (4) |

| 001 | Center | Potassium (K) |

1.4 (0.8–2.0) |

2017–2022 (4) |

| 001 | Center | Sulphate (SO4) |

6 (3–8) |

2017–2022 (4) |

NPS

Indian Springs Canyon Spring

Indian Springs Canyon Spring (Figure 11) is a rheocrene spring (a spring that emerges into one or more stream channels) in Indian Springs Canyon. The spring has a strong hydrologic connectivity to the water level of Amistad Reservoir, and as a result, the emergence location for this spring is highly variable. In WY2018, WY2019, and WY2020, the spring emerged 500 m upstream of the canyon’s mouth (orifice A; Figure 12). In WY2022, the spring emerged at the mouth of the canyon (orifice G), and in WY2023, it emerged about 100 m upstream of the canyon’s mouth (orifice H). Spring characteristics vary depending on emergence location, but the spring typically forms standing, elongated pools or a stream slowly flowing over cobble and bedrock. The springbrook has measured over 100 m in length in previous years. The WY2023 visit occurred on 03 April 2023, and the spring was wetted (contained water) at orifice H, but all other previously named spring orifices were dry.

NPS

Site Condition

Site condition was assessed around orifice H, about 100 m upstream from the mouth of Indian Springs Canyon. In WY2023, We rated Indian Springs Canyon Spring moderately disturbed by contemporary human use, with the presence of trash (cans, shoes, etc.) and social trails (rated undisturbed to slightly disturbed in the past); moderately disturbed by drying because there was a dearth of obligate wetland species and the riparian area was choked by invasive plants (rated undisturbed to highly disturbed in the past); and moderately disturbed by wildlife based on tracks and sightings (rated undisturbed in the past). No other natural or human-caused disturbances were observed at Indian Springs Canyon Spring in WY2023.

We did not observe the invasive non-native American bullfrog (Lithobates catesbeianus) at Indian Springs Canyon Spring in WY2023. We observed six species of invasive non-native plants: evenly distributed patches of seaside petunia (Calibrachoa parviflora, not previously observed); 1–5 straggler daisy plants (Calyptocarpus vialis, not previously observed); scattered patches of bermudagrass (Cynodon dactylon, 1–5 plants to a matrix observed in 2018–2022); 1–5 little bur-clover plants (Medicago minima, not previously observed); scattered patches of tree tobacco (Nicotiana glauca, scattered patches observed in 2022); and a matrix of lilac chastetree (Vitex agnus-castus, 1–5 plants to scattered patches observed in 2017–2022).

We did not observe any obligate/facultative wetland plants at Indian Springs Canyon Spring in WY2023.

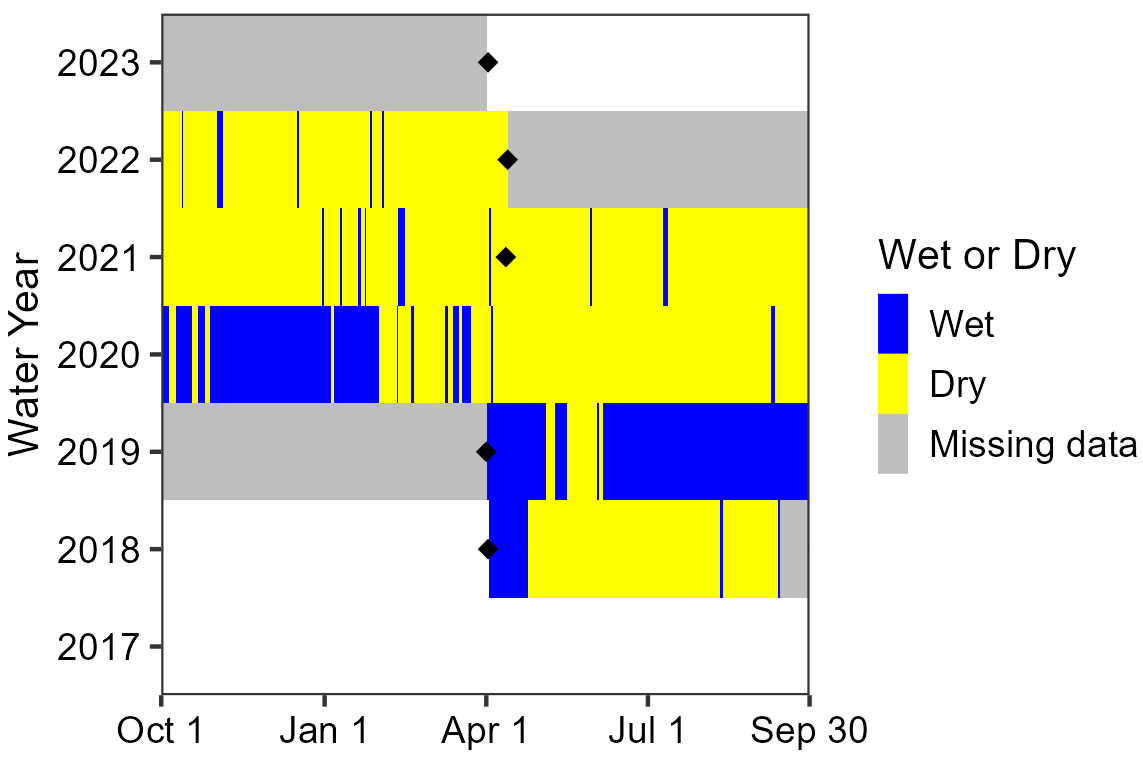

Water Quantity

Sensors are deployed and data are downloaded during our annual visit, which takes place in the middle of the water year; the dates of these visits are indicated by black diamonds in the persistence graph (Figure 13). From 2018 to 2023, water persistence was monitored at orifice A. The temperature sensor deployed in April 2022 was not found during the WY2023 visit, so persistence data are missing for WY2023. In prior water years, the spring was wetted 3.6–86.7% of the days measured.

NPS

Discharge was not measurable at Indian Springs Canyon Spring in WY2023 because of a lack of surface flow. No prior discharge measurements are available.

Wetted extent was evaluated using a method for flowing water. The total springbrook length was 54.4 m (178.4 ft). In the past, measured springbrook length in WY2023 ranged from 27.0 m (88.6 ft) to an estimated 100–200 m (328–656 ft). Width and depth along the springbrook averaged 5.6 m (18.3 ft) and 19.6 cm (7.7 in), respectively. The springbrook in WY2023 was within the range of previous length measurements, but it was slightly wider and deeper on average (Table 11).

Water Quality

Core water quality (Table 12) and water chemistry (Table 13) data were collected at orifice H (sampling location 008). Values from WY2022, taken at orifice G (sampling location 007) are presented for context, but continued monitoring is needed before meaningful comparisons can be made.

Indian Springs Canyon Spring Data Tables

| Measurement | WY2023 Value (range of prior values/means) |

Prior Years Measured (# of visits with measurements) |

|---|---|---|

| Width (m) | 5.6 ± 3.3 (1.8–4.5) | 2017–2022 (4) |

| Depth (cm) | 19.6 ± 16.4 (3.5–18.2) | 2017–2022 (4) |

| Length (m) | 54.4 (27.0–100.0) | 2017–2022 (4) |

| WY2023 Sampling Location (WY2022 sampling location) |

Measurement Location | Parameter | WY2023 Value (range of prior values) |

Prior Years Measured (# of measurements) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 008 (007) | Center | Dissolved oxygen (mg/L) | 5.62 (6.32) |

2022 (1) |

| 008 (007) | Center | pH | 7.59 (7.37) |

2022 (1) |

| 008 (007) | Center | Specific conductivity (µS/cm) | 399.1 (395.2) |

2022 (1) |

| 008 (007) | Center | Temperature (°C) | 23.5 (23.5) |

2022 (1) |

| 008 (007) | Center | Total dissolved solids (mg/L) | 259 (257) |

2022 (1) |

| WY2023 Sampling Location (WY2022 sampling location) |

Measurement Location | Parameter | WY2023 Value (range of prior values) |

Prior Years Measured (# of measurements) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 008 (007) | Center | Alkalinity (CaCO3) |

150 (150) |

2022 (1) |

| 008 (007) | Center | Calcium (Ca) |

52 (54) |

2022 (1) |

| 008 (007) | Center | Chloride (Cl) |

5 (5) |

2022 (1) |

| 008 (007) | Center | Magnesium (Mg) |

17 (11) |

2022 (1) |

| 008 (007) | Center | Potassium (K) |

1.3 (0.4) |

2022 (1) |

| 008 (007) | Center | Sulphate (SO4) |

0 (0) |

2022 (1) |

NPS

Mouth of the Pecos Spring

Mouth of the Pecos Spring (Figure 14) is a limnocrene spring (a spring that emerges to form one or more stagnant pools) located in a side canyon of the Lower Pecos River, just upstream from its confluence with Amistad Reservoir. When flowing, the spring emerges from two orifices to form small pools surrounded by boulders in the canyon bottom before dispersing into a marshy area populated by cattails. The WY2023 visit occurred on 30 March 2023, and the spring was dry. We did not collect data at Mouth of the Pecos Spring in WY2022 because of logistical and time constraints.

Site Condition

In WY2023, we rated Mouth of the Pecos Spring slightly disturbed by contemporary human use because of trash along the banks (rated slightly disturbed in the past); slightly disturbed by feral animals with horse/burro manure in the streambed (rated undisturbed to slightly disturbed in the past); slightly disturbed by wildlife because of tracks and scat (rated undisturbed to slightly disturbed in the past); moderately disturbed by roads/OHVs based on a parking area that is located less than 100 m from the site, though there was minimal to no impact on vegetation/soils (rated undisturbed to slightly disturbed in the past); and highly disturbed by drying since the spring was dry, but some wetland obligates were still present (rated undisturbed to highly disturbed in the past). No other natural or human-caused disturbances were observed at Mouth of the Pecos Spring in WY2023.

We did not observe the invasive non-native American bullfrog (Lithobates catesbeianus) at Mouth of the Pecos Spring in WY2023. We observed three species of invasive non-native plants: a matrix of giant reed (Arundo donax, evenly distributed patches to a matrix observed in 2018–2021); scattered patches of bermudagrass (Cynodon dactylon, scattered patches to a matrix observed in 2017–2021); and scattered patches of tamarisk (Tamarix sp, not previously observed).

We observed four species of obligate/facultative wetland plants at Mouth of the Pecos Spring in WY2023: cattail (Typhaceae, a grass observed in 2017–2021); giant reed (Arundo donax, a grass observed in 2018–2021); mule-fat (Baccharis salicifolia, a shrub observed in 2017–2021); and tamarisk (Tamarix sp., a tree/shrub observed in 2018).

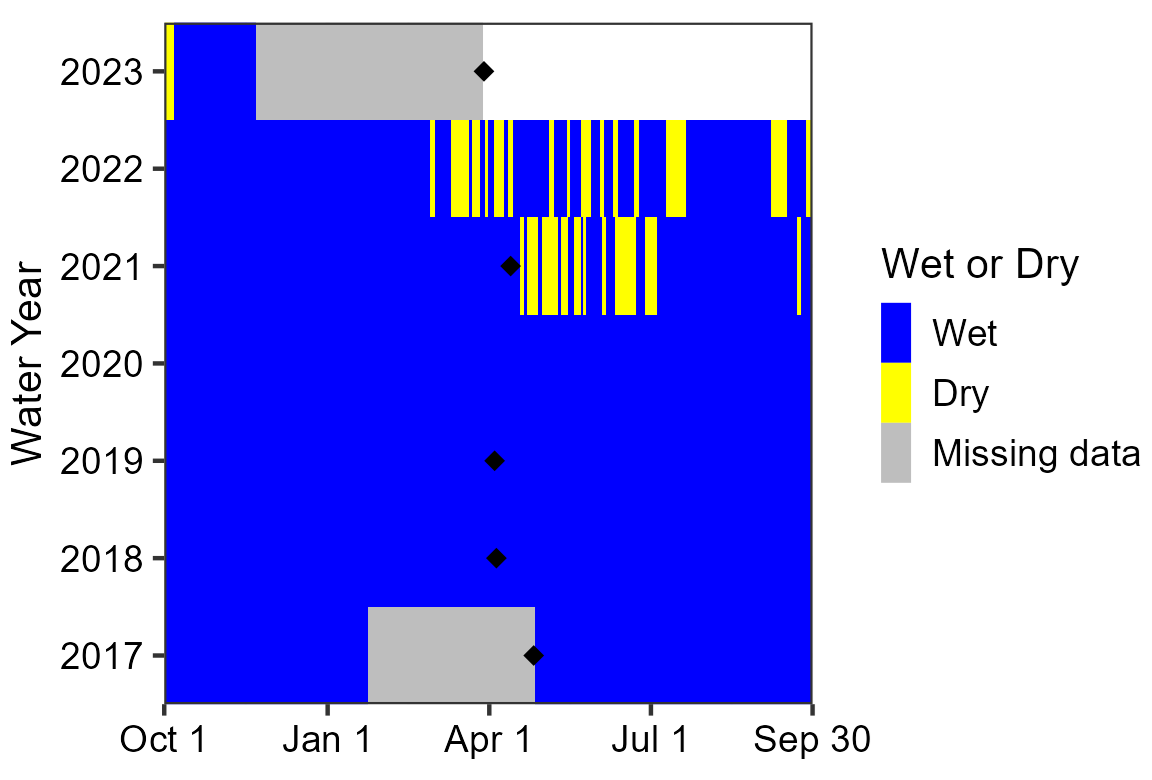

Water Quantity

Sensors are deployed and data are downloaded during our annual visit, which takes place in the middle of the water year; the dates of these visits are indicated by black diamonds in the persistence graph (Figure 15). The temperature sensor indicated that Mouth of the Pecos Spring was wetted for 46 of 52 days (88.5%) measured up to the WY2023 visit. In prior water years, the spring was wetted 80.8–100% of the days measured.

NPS

Discharge was not measurable in WY2023 since the spring was dry at the time of the visit. Discharge estimates are available for one prior year (2019) when it was estimated at 23.1 L/min (6.10 gal/min; Table 14).

Wetted extent (a measure of length, width, and depth of surface water) was not measurable in WY2023 since the spring was dry, but wetted extent data for WY2019 are included in Table 15.

Water Quality

Core water quality (Table 16) and water chemistry (Table 17) data were not collected in WY2023 since the spring was dry. We report previous (2018–2019) values in the tables.

Mouth of the Pecos Spring Data Tables

| Sampling Location | WY2023 Mean (range of prior means) |

Prior Years Measured (# of visits with measurements) |

|---|---|---|

| 006 | c.n.s. (23.1) | 2019 (1) |

| Measurement | WY2023 Mean (range of prior means) |

Prior Years Measured (# of visits with measurements) |

|---|---|---|

| Width (m) | c.n.s. (3.8–4.2) | 2018–2019 (2) |

| Depth (cm) | c.n.s. (43.7–45.0) | 2018–2019 (2) |

| Length (m) | c.n.s. (2.6–5.3) | 2018–2019 (2) |

| Sampling Location | Measurement Location | Parameter | WY2023 Value (range of prior values) |

Prior Years Measured (# of measurements) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 005 | Center | Dissolved oxygen (mg/L) | c.n.s. (2.79–3.77) |

2018–2019 (2) |

| 005 | Center | pH | c.n.s. (7.35–7.40) |

2018–2019 (2) |

| 005 | Center | Specific conductivity (µS/cm) | c.n.s. (553–553) |

2018–2019 (2) |

| 005 | Center | Temperature (°C) | c.n.s. (22.7–23.6) |

2018–2019 (4) |

| 005 | Center | Total dissolved solids (mg/L) | c.n.s. (357.5–357.5) |

2018–2019 (2) |

| Sampling Location | Measurement Location | Parameter | WY2023 Value (range of prior values) |

Prior Years Measured (# of measurements) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 005 | Center | Alkalinity (CaCO3) |

c.n.s. (210–235) |

2018–2019 (2) |

| 005 | Center | Calcium (Ca) |

c.n.s. (54–56) |

2018–2019 (2) |

| 005 | Center | Chloride (Cl) |

c.n.s. (15–24) |

2018–2019 (2) |

| 005 | Center | Magnesium (Mg) |

c.n.s. (18–20) |

2018–2019 (2) |

| 005 | Center | Potassium (K) |

c.n.s. (1.5–1.9) |

2018–2019 (2) |

| 005 | Center | Sulphate (SO4) |

c.n.s. (29–31) |

2018–2019 (2) |

Report Citation

Authors: Kara Raymond, Susan Singley

Raymond, K., and S. Singley. 2025. Climate and Water Monitoring at Amistad National Recreation Area: Water Year 2023. Chihuahuan Desert Network, National Park Service, Las Cruces, New Mexico.