Part of a series of articles titled People of the California Trail.

Article

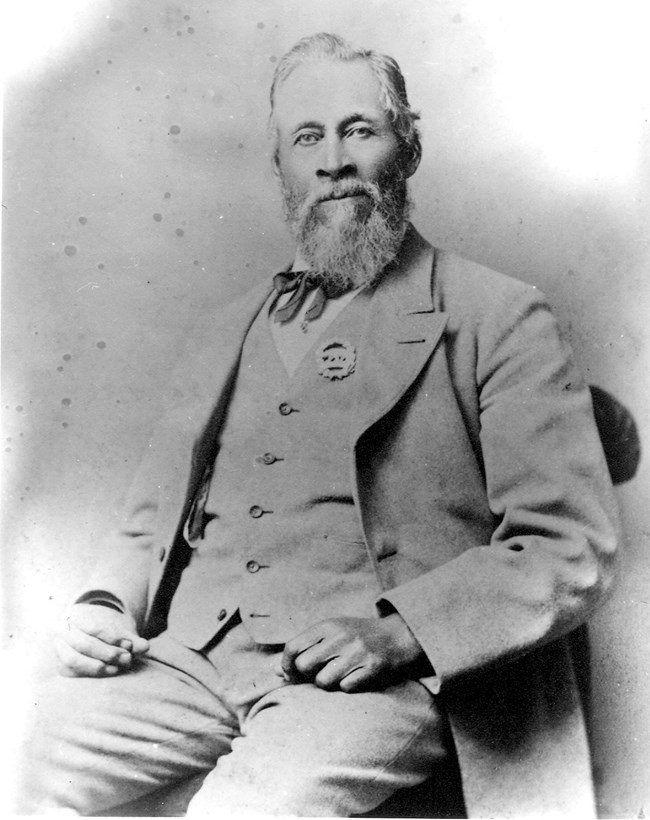

Alvin Aaron Coffey, the California Trail

Image/Public Domain

Alvin Aaron Coffey – California Trail[1]

By Angela Reiniche

California was a place of both hope and danger for enslaved African Americans. The state’s antislavery laws and plentiful business opportunities provided chances for a fresh start. These business opportunities, however, also attracted dishonest men looking to earn a quick buck. As we shall see, Alvin Coffey experienced both extremes during his three journeys across the California Trail.

Alvin Aaron Coffey began his life in Mason County, Kentucky, on 14 July 1822. He was born enslaved. At the age of twelve, his enslaver Margaret Cooke sold him to Henry H. Duvall, who took him to Missouri. In 1846, Duvall sold Coffey to a doctor by the name of William Bassett. Lured by the promise of gold, Bassett took Coffey with him to California, forcing the twenty-seven-year-old to leave behind his pregnant wife, Mahala, and their two children.

The wagon train for his first overland trip, consisting of twenty wagons and somewhere between sixty and one hundred men, left St. Joseph on 2 May 1849. Along the way, Coffey performed a number of essential duties, such as managing the oxen, tending to livestock, and driving the wagons. Coffey’s expertise as an ox-team driver (or ‘bullwhacker’) was unsurpassed, as he recalled in a memoir of his experiences. When his California-bound party was two days away from Honey Lake on the Nobles Trail, they made camp at Rabbit Hole Springs where the Nobles Trail branched off the Applegate Trail. Here an ox gave out and Coffey had to put him down with two double-barreled shotguns because he could not bear the sound of the animal’s bawling—and the thought that the wolves might eat him alive. He reserved three shots for the wolves in case they came after him.[2]

Coffey often chastised other drivers that did not know how to handle their oxen, especially for overworking them; he prided himself on knowing “about how much an ox could stand.”[3] Coffey also shared duties as a night guard, watching over the camp and its livestock in six-hour shifts. Jeanette Molson, Coffey’s descendant, concludes that her ancestor’s shared night-watch duties suggest “to some degree” that “he was treated pretty much as an equal.”[4] Yet no amount of respect could shield Coffey from the hardships of disease along the trail, specifically cholera (which killed one man in his party). Coffey noted in his biography, “we get news every day that people were dying by the hundreds in St. Joe and St. Louis. It was alarming.”[5]

Before leaving Missouri, Coffey arranged to buy his freedom from Dr. Bassett with money earned from prospecting; Coffey was perhaps unaware that California’s constitution prohibited slavery. After arriving at the mines in the fall of 1849, Bassett revealed that he had other plans. He hired Coffey out to others and kept the money that Coffey earned as a cobbler, laundryman, and miner. Despite his objections, Coffey saw all seven hundred dollars from his side work go right into Bassett’s pocket.[6] Coffey’s California prospects were further imperiled by the fact that white miners protested working alongside Black men, whether free or enslaved. California’s legislature enacted a “Foreign Miners Tax” of four dollars a month and collected it, sometimes forcibly, not only from South American and Chinese miners, but also from African American and Indigenous miners. Yet despite this attempt to discourage African American miners, there are no less than thirty place names in California that affirm the presence of Black forty-niners.

Coffey wrote in his memoir that he might have been able to escape from Bassett in California, but he was afraid that—if he failed—he would end up on the auction block in New Orleans. Bassett took Coffey back to Missouri in 1853 and sold him to Mary Tindell for $1,000—thus setting in motion Coffey’s second journey to California in 1854. Tindell’s son Nelson handled most of the transactions concerning Coffey. Tindell’s other son, Ben, who had himself just returned from California, convinced Nelson to let Coffey to return to working in the gold mines to earn his freedom. Nelson was at first reluctant, but Coffey reasoned with him and agreed to a manumission fee of $1,000. Coffey then headed west with Ben Tindell, earning extra money along the way by hiring himself out for a variety of jobs. He was in California from 1854 to 1857, working for his new owner and himself at the Shasta and Sutter mines. There he made enough to buy himself, his wife, and his children out of slavery. Unlike Bassett, Tindell held up his end of the bargain and Coffey became a free man.[7]

Alvin Aaron Coffey made his third, and final, overland trip as a free man. With his manumission papers in hand, he returned to Missouri for his “pretty Mahala” and their children. It took two months and the help of an attorney to make sure that his wife, their two daughters, and three sons had been legally manumitted. Alvin, Mahala, and their three sons—John, Alvin Jr., and Stephen Coffey—left Missouri in April 1857 and set out for Shasta County, California. (Alvin left his two daughters in the care of their grandmother in Ontario, Canada.) The year after they arrived, Coffey founded a school for African American and Indigenous children. Shortly thereafter, the family relocated to Red Bluff, in Tehama County, California. Coffey retrieved his daughters from Canada via the Isthmus of Panama in 1860 and brought them home to Red Bluff, where they prospered as farmers, turkey ranchers, and laundry operators.[8]

In 1887, the Society of California Pioneers inducted Coffey, the only African American to earn this particular honor. He died on 28 October 1902 in Alameda County, California, in the Beulah Home for Aged and Infirmed Colored People—yet another institution he had helped establish.[9] Alvin Coffey’s story is one example of how, at the far western end of the California Trail, enslaved African American emigrants found ways to negotiate their freedom in the antebellum American West.

[1] Part of a 2016–2018 collaborative project of the National Trails- National Park Service and the University of New Mexico’s Department of History, “Student Experience in National Trails Historic Research: Vignettes Project” [Colorado Plateau Cooperative Ecosystem Studies Unit (CPCESU), Task Agreement P16AC00957]. This project was formulated to provide trail partners and the general public with useful biographies of less-studied trail figures—particularly African Americans, Hispanics, American Indians, women, and children.

[2] Shirley Ann Moore, Sweet Freedom’s Plains: African Americans on the Overland Trails 1841-1869 (Santa Fe: National Trails Intermountain Region, National Park Service, 2012), 133; Sue Bailey Thurman, Pioneers of Negro Origin in California (1952), 12; Coffey, “Autobiography of Alvin A. Coffey,” The Pioneer (reprint; December 2000): 10-13; Alvin A. Coffey, “The Autobiography of Alvin A. Coffey,” Overland Journal 20, no. 2 (Summer 2002): 64-73. Robert Clark, Don Buck, and Tom Hunt, who wrote an intro and notes for this version, point out that Coffey was mistaken about some dates, geographic details, and place names, perhaps confusing his 1849 crossing with subsequent trips.

[3] William Loren Katz, from Coffey’s memoir, reprinted in The Black West: A Pictorial History, 3rd ed.(Seattle: Open Hand Publishing, 1987), 118-119.

[4] Jeanette Molson interview in Moore, Sweet Freedom’s Plains, 146; and Coffey, “The Autobiography of Alvin A. Coffey,” Overland Journal, 69.

[5] Coffey, “Autobiography of Alvin A. Coffey,” The Pioneer, 11.

[6] Molson and Blansett, The Tortuous Road to Freedom: The Life of Alvin Aaron Coffey (Linden, Calif: self-published, 2004), 74.

[7] Moore, Sweet Freedom’s Plains, 169-70.

[8] Ibid., 170-71.

[9] Ibid, 171.

Last updated: March 7, 2023