Last updated: September 2, 2021

Article

Alex Petrovic Oral History Interview

NPS

ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW WITH ALEX PETROVIC

AUGUST 19, 1991INDEPENDENCE, MISSOURI

INTERVIEWED BY JIM WILLIAMS

ORAL HISTORY #1991-22

This transcript corresponds to audiotapes DAV-AR #4369-4371

HARRY S TRUMAN NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR

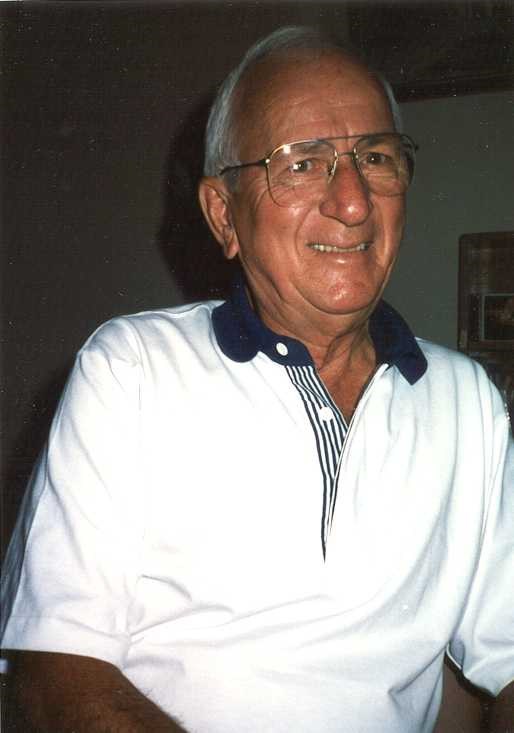

ALEX PETROVIC

19 August 1991

HSTR Photograph

EDITORIAL NOTICE

This is a transcript of a tape-recorded interview conducted for Harry S Truman National Historic Site. After a draft of this transcript was made, the park provided a copy to the interviewee and requested that he or she return the transcript with any corrections or modifications that he or she wished to be included in the final transcript. The interviewer, or in some cases another qualified staff member, also reviewed the draft and compared it to the tape recordings. The corrections and other changes suggested by the interviewee and interviewer have been incorporated into this final transcript. The transcript follows as closely as possible the recorded interview, including the usual starts, stops, and other rough spots in typical conversation. The reader should remember that this is essentially a transcript of the spoken, rather than the written, word. Stylistic matters, such as punctuation and capitalization, follow the Chicago Manual of Style, 14th edition. The transcript includes bracketed notices at the end of one tape and the beginning of the next so that, if desired, the reader can find a section of tape more easily by using this transcript.Alex Petrovic and Jim Williams reviewed the draft of this transcript. Their corrections were incorporated into this final transcript by Perky Beisel in summer 2001. A grant from Eastern National Park and Monument Association funded the transcription and final editing of this interview.

RESTRICTION

Researchers may read, quote from, cite, and photocopy this transcript without permission for purposes of research only. Publication is prohibited, however, without permission from the Superintendent, Harry S Truman National Historic Site.ABSTRACT

Alex Petrovic (b. Sept. 23, 1922) from 1962 to 1966 was state representative in the Missouri legislature for the district that includes the Truman home. He then served for four years as the eastern district judge for Jackson County. These positions brought him into occasional contact with the Trumans, through which he is able to reveal Mr. Truman’s interest in local political affairs through 1970. His visits to the home were infrequent, but they represent an aspect of this era in the life of Harry S Truman. Petrovic discusses growing up in Independence as a son of immigrants and participating in civic activities such as the Sertoma Club. He describes local political rallies, the development of the Truman Sports Complex, and Truman’s opposition to a local college campus change.Persons mentioned: Harry S Truman, Dwight D. Eisenhower, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Rose Conway, John F. Kennedy, Bess W. Truman, Douglas MacArthur, Benedict K. Zobrist, Margaret Truman Daniel, Ray Zackovich, Richard M. Nixon, Noel Fields, Dutton Brookfield, Charles Deaton, Charles Wheeler, Steven Young, Burch Bayh, Thomas Eagleton, Hubert H. Humphrey, Ewing Kauffman, Phil Corey, William Rockhill Nelson, F. Lee Bailey, Fran Petrovic, Cass Curan, Billy Jones, Elizabeth Bush Sapper, Dorsy Lou Warr, Louis “Polly” Compton, Tom Walsh, Ernest Posner, Thomas Hart Benton, Pete Saxton, Robert Kennedy, Earl Long, John Hayner, Homer Clemens, Carol Roper, Al Petrovsky, Richard Brownlee, Gene Sanders, Warren Hearnes, Joe Bolger, and Herbert C. Hoover.

ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW WITH ALEX PETROVIC

HSTR INTERVIEW #1991-22JIM WILLIAMS: This is an oral history interview with Alex Petrovic. We’re at the Truman Library on the morning of August 19, 1991. The interviewer is Jim Williams from the National Park Service, and Leslie Hagensen from the National Park Service is running the recording equipment.

First of all, I need to ask you, are you a native of Independence?

ALEX PETROVIC: Sort of. I was born in Kansas City, September 23, 1922, and we moved, my family, my mother, and father moved to Independence, Missouri, in 1929, where I lived at 24 Highway and Kiger Road, just east of here.

WILLIAMS: Growing up, how aware were you of politics, the Truman family, and that kind of thing?

PETROVIC: Well, in Jackson County, as you’ve already found out, politics just seems to be second nature. I was aware of the way they used to solicit votes. I can remember we had a large family, eight of us in the family. My mother and father were immigrants from Yugoslavia, Serbia specifically, and whenever county elections came along, the county trucks would quite often drive up with a load of gravel, because we had quite a large, long driveway, and they would gravel the driveway for us. I found that kind of interesting, as an

5

observer watching how county politics works, but there was no suggestion that we vote for anybody at that time. And I’m sure Harry Truman was . . . of course, at that time, was a presiding judge, I believe, of the county court, or running for presiding judge. But the appreciation, the county people would introduce themselves and would just want to drop off some gravel. So that was kind of an interesting introduction.

But I was just sort of a spectator as a young man until later years when I got back from my service in the marine corps and then settled in Sugar Creek where my wife . . . When we were married and I got back from the service, that was the only place we could find was a little flat in Sugar Creek, and I’ve lived there ever since.

WILLIAMS: When did you get back from the service?

PETROVIC: About 1945.

WILLIAMS: So you were in World War II.

PETROVIC: Right. I joined the marine corps out of . . . graduated out of William Chrisman High School in Independence and joined in July of 1942 and served in the South Pacific.

WILLIAMS: Need I ask which political party your family . . .

PETROVIC: Well, they’re Democrats. My father was just a dyed-in-the-wool Roosevelt Democrat, and Truman was . . . He admired Harry Truman until an incident occurred. We had a nice size home on 24 Highway and Kiger Road, which was later destroyed by fire. It’s right on the corner where the RLDS church is there, on the north side of the street. And my father had an FHA loan. And he was a salesman, a coffee salesman at that time before

6

A&P started grinding coffee and all the little supermarkets came about. My father sold to small grocery stores all over Missouri and Kansas in this metropolitan area, candy and coffee and that type of thing, packaged their own coffee. And so my father had difficulty in the thirties in making his house payments. Truman was a senator at the time, and I think he had met him. My father . . . The story is pretty emblazoned in my mind. My father went to the courthouse in Independence to visit with Truman to see if Truman could intercede for him with the FHA to give him some time to make up his payments rather than face foreclosure. And Truman made the remark to my father that . . . something like this, that “You people, the minute you get a loan from the federal government, you don’t think you have to pay it back.” And it upset my father so much, and embarrassed him, that from that time on he had very little regard for Truman, even though I still think he voted for him until the Eisenhower years. That bothered him because he later made up his payments and saved the house. It didn’t go into foreclosure, but it embarrassed him to a point that he never forgot it.

WILLIAMS: So you were in the service in the war when Mr. Truman became vice president and president.

PETROVIC: Yes.

WILLIAMS: What did you think of that, coming from Independence?

PETROVIC: Well, I can remember I was in California when President Roosevelt had died. I was stationed at a base at Camp Kearny in California, and everybody knew that I was from Independence because Vice President Truman at that time had some notoriety. And when he became president after the death of

7

Roosevelt, at that almost precise moment people would gather around me. And I was just as stunned as the rest of them because, you know, Roosevelt was going to live forever. And everybody wanted to know what Truman was really like, and they were fearful that he wasn’t going to be the man, of course, that Roosevelt was. So a lot of people just said, “Did you know him? And what kind of a man is he? Are we safe?” I mean, the security of the country was at stake, and I think they were rightfully concerned.

But gradually those fears were allayed, by virtue of the fact of just further examination and the public got to know him better. I really admired Truman way back there for his work with the Truman investigation committee. You know, he always went after . . . I think he was quoted one time with something like saying that, “I’ll let the other politicians go after the big things; I’ll go after more of the housekeeping things.” And that’s where I think he got the idea of the Hoover Commission after he became president and made those reforms. But he was a fighter and a fiercely independent politician that we all admired.

Some of this is in retrospect. When I became eastern judge, I came over here to the library and spent about six or seven hours studying his administration. I’d heard a lot about it but I just . . . Rose Conway, we were good friends, and I used to bring a lot of people over here. The Koreans always made a kind of a pilgrimage to come over here and thank him, and others. But to study what he did, and he was a man who did his political term in the most political time, when you wondered how he could become independent, but he was a rare gentleman and he was so clean and

8

yet played his normal politics and yet ran his own show for the most part, and I admired that in him.

WILLIAMS: When these people were asking you, “Can Truman do it?” were you confident that he could be president?

PETROVIC: Yeah, I think there was a lot of pride in the fact that he was from Independence, and I just had kind of a blind faith in him. Yeah. I mean, I don’t recall being embarrassed about it, because there was the comparison of the two men—it was just night and day—and we were all worried, and very sad. It was almost as sad as the time when John Kennedy was killed, it was that kind of a feeling. But I felt like he could do it, just based on what I knew about him. He was never involved in a scandal, and I think he was selected because he had something on the ball.

WILLIAMS: What’s your first personal memory of Mr. Truman, your first meeting with him or glimpse of him even?

PETROVIC: When I was in the state legislature, I had the opportunity to attend some functions where he was here. I went to the train station when he came home, which was a very, very poorly attended meeting, when he came home on the train from Washington.

WILLIAMS: Which time?

PETROVIC: Well, when he was . . . his last term, when he left office the last time, when he was through his presidency. And at the railroad station, I’m still saddened at the looks of the station. I was over there here about a month ago, and the way they’ve let that thing fall into disrepair is a surprise. And I don’t understand it, why somebody doesn’t take care of that. He was there.

9

And I was also at a meeting, and I can’t recall when, it was before I was in public office, at the courthouse when they honored him for something and he spoke on the courthouse steps on the south side of the courthouse. And it might have been at the time he was responsible for remodeling that, so I don’t know . . . I can’t place that as to whether he was a senator or still a judge, but I think he was . . . I think he came there for some other reason, as a senator or a vice president.

And then I think my first real encounter with him, in my recollection, was at the Sertoma Club where I sat with him and was just scared to death. I was looking at my scrapbooks before I got here, and I remember him throwing his hand . . . He was sitting next to me, and Mrs. Truman over there, and my wife wanted to know what to say to Mrs. Truman. He said, “I think you told me that you have a large family.” He said, “Tell her to talk about kids,” which she did, and she had a delightful evening. She was as scared as I was, and yet I’d been around politically. My wife was more of a homemaker, but she enjoyed herself, as she later told me. But he reached over and put his hand on my leg and said, “I just want you to treat me like a neighbor tonight and like an old shoe, so let’s just have some fun and relax and enjoy.” Well, I mean, it didn’t totally relax me, but it made me feel pretty good.

And then I had asked him that night about . . . See, I had wired Truman. I guess I was driving along the road one time and the MacArthur thing was flaring up. And having been in the marine corps, I felt very strongly that the commander in chief ought to have a say-so, and I pulled

10

over to the side of the road and composed a telegram and sent it to him. And it’s in the library. I mentioned that to Ben Zobrist one time as I was bringing some people through here, and he said, “Alex, if you sent a telegram, it’s here.” Then I thought to myself, “Oh, my God, did I just . . . Did the years . . . Did I just think I sent it, or did I really send it?” And by the time I finished the tour he had the telegram here supporting [Truman’s firing of] MacArthur. I had reminded Mr. Truman at the time of the Sertoma meeting over at the Rockwood Country Club that I did support him and sent the wire, which he again thanked me and said it was something he had to do.

And then I also sent Margaret Truman a wire when she made her singing debut and was severely criticized, and got a nice letter of acknowledgement back from that. And he told me that night in very colorful terms at the Rockwood when that subject came up, and I told him that Margaret . . . I went to school with Margaret and was in a school play with her and so I told him that I had sent the wire, and he said, “Well, Margaret and Mrs. Truman didn’t want me to assail this music critic,” he said, “but the son of a bitch didn’t do too bad. He made $8,000 on the letter that I wrote him.” [chuckling] So that was his way of saying that. He was a very salty guy. [See appendix items 1-2.]

Then I had met him a number of times, bringing people over here, and one time he asked me to represent him. They were going to close this college down over here, the CMSU, Central Missouri State University, and I was in the Missouri legislature, and the Commission on Higher Education

11

was going to hold a hearing and I was to be the master of ceremonies since this was my district. I represented the Truman family in my district. So I came over here asking him, or had inquired from Rose Conway as to whether or not he would testify, since all he’d have to do is to walk across the street literally, because that’s where the hearing was. And she said he couldn’t, but he wanted to see me before I went over there. So I came in the back door, as I usually did, and he sat there and told me to tell the committee the following kind of thing. And he said, “You just tell them that he doesn’t think it’s in the national interest to close this college,” you know. I mean, it was kind of a . . . And he said, “I want you to quote me as much as you can remember, and you just tell them that they don’t . . .” and some other . . . You know, he always was very fond of the kids, and he said this was one of the reasons why he allowed that unit to be built there next to the library is because he had such a fondness for these kids and he wanted them to have a sense of history. And he said, “If those people don’t believe what you say, you just tell them to come over here and jump over the hedge, and I’ll be here and I’ll tell them myself.” Well, I told the committee that, and that just wilted . . . We won the battle, at least for that period. And they had some big hitters here trying to close it down and to assimilate that into the university in Kansas City. [See appendix item 3.]

WILLIAMS: So that’s the reason they were trying to shut it down?

PETROVIC: Yeah, they wanted to move it into Kansas City, and then Warrensburg university that had started this little branch wanted to keep it, but they were going to kind of use it as some other facility, not as it was intended. It

12

would not have been accredited as it was here.

And then I met him a good number of times when I would bring people over here that would come through the courthouse in Independence. And being eastern judge at the time, it was kind of the protocol for those visitors, VIPs, to be ushered over here.

Now, one rather interesting incident. Pat Paulsen, do you recall that name?

WILLIAMS: He ran for president.

PETROVIC: Okay, he ran for president and I was . . . I had got a call from his publicist and somebody else who was going to escort him around. I can’t recall who that was at this moment, but they said, “Would you take him over to Truman Library and have him meet the president?” So I said, “Well . . .” I called Rose Conway, and Rose Conway said . . . She was always extremely proper, never to actually quote the president, but to say that “I’m sure that he wouldn’t like this,” but I knew how that went. I always had great admiration for how confidential of a secretary she was and how she protected him from having any quotes from him.

But anyway, he didn’t want to see him because he felt that he demeaned the presidency by running in that manner, and so I was to report to him that he wasn’t feeling very good and he couldn’t see him. So the interview was canceled. And so I brought him by the library, only on the periphery here, and he was . . . He was too embarrassed himself. He sensed it, so we went to the Truman home and stood in front of the Truman home and took some pictures, none of which I have. I didn’t get any copies

13

of it. And then after a moment or two, knowing that the Trumans were probably at home at the time—as a matter of fact they were—he said, “I’m just a little bit embarrassed. I feel like I ought to leave.” So he left, and I took him back to the courthouse in Independence.

WILLIAMS: Let me ask you about a few things you’ve mentioned. You said you were at the train station when Mr. Truman returned from Washington?

PETROVIC: Mm-hmm.

WILLIAMS: Could you describe more about the atmosphere?

PETROVIC: Well, it was kind of a somber thing, and not very well attended. I, among others, was embarrassed that the town didn’t turn out in the force that we thought it would be. He was kind of a beaten president from the press and all this other business, and so I just felt, out of respect to him . . . It’s the same feeling I felt when he died. I knew a number of Secret Service people, one of them who was very prominent and one of my countrymen, a Serbian named Ray Zackovich, who I’m sure you’ve talked to, and I could have gotten a pass to come right directly, bypassing the crowd. And my family and myself and my sister-in-law chose to stand. And we were up there by Hi Boy Restaurant when we got into the line on that cold night. I never wanted to use any political influence, and I didn’t think he would have either, to wait to review . . . to pass in front of him. So his humility . . . I mean, everyone was trying to be a Harry Truman. I mean, he’s probably the most quoted president in the world, including Richard Nixon. The president told me one time he didn’t know how in the hell that Nixon got the idea that the “Missouri Waltz” was something he wanted to hear.

14

And so, when he was at the train station, I can’t recall having shook his hand or anything. I might have, but I don’t remember that. I just remember being there.

WILLIAMS: Well, you said the crowd was disappointing. How many people were there?

PETROVIC: In my recollection, and, you know, I can be wrong, but I can’t estimate more than a hundred or so people.

WILLIAMS: And this Sertoma Club event, was that after he was president? [See appendix items 4-9.]

PETROVIC: No, that was when he was home. That was after he was president, yeah, and he was really doing quite a bit of community work. And we didn’t even . . . We knew we had a lot of people there who were Sertoma members. There were a half a dozen that knew him well, and so they prevailed on him to come there, and he accommodated Noel Fields and some others who were very close to him. I had a nice time. I have a picture of him and his wife in front of . . . The Sweet Adelines sang that night, a big group, and I have the picture. [See appendix item 9]. If you ever have any interest in looking at those scrapbooks, or if Ben does, there’s some stuff that the library doesn’t have that I think might be interesting.

But he was extremely gracious. She didn’t want to take any pictures. He whispered to me, he said that . . . on this side of him, he said, “Mrs. Truman doesn’t want to take any pictures a little later on with the Sweet Adelines.” And that was a request that we had had after the program. But he said, “You just keep insisting. You just keep insisting.”

15

And she stood up and so on. She was extremely soft-sell . . . I’m not being a male chauvinist when I . . . Simply, she just seemed to know her place in the picture.

The prime example of that, if I can jump to another matter, is when I visited the Truman home the second time. Yeah, the second or third time. The second time. The first was an inspection of the tile that was laid in the bathrooms upstairs—one bathroom, if I remember—and the second one was when I had proposed the name of the Truman Sports Complex to be after Harry Truman. I called Rose Conway and said, “I’d like to name it . . . I understand Mrs. Truman was a great baseball fan. What do you think? Will you check for me?” So she checked and she said, “Only under the following condition, and that is that his name . . . that he did not suggest it, and that after the court order is finally passed,” because I had proposed it in a speech I made in Kansas City in front of the Blue Valley Lions Club, I believe, “and if after the court approves it,”—it was a three-judge court, Judge Curry, Judge Wheeler, and myself—“then you call me and I’ll arrange for you to visit with him and bring him . . .” I wanted to bring him a picture of the sports complex. So after it was over with, I got a call from Rose Conway and she said, “The president will see you.” And I had an artist’s conception of the sports complex, and I had all the principals sign it, the architect and Judge Curry, Judge Wheeler, myself, and Dutton Brookfield, and Charles Deaton who designed it, and so on, and so I was to meet him at the home.

And so I went over there, and Mrs. Truman met me at the door and

16

said, “If you’ll come in . . .” and they seated me in the front room of the house, the one that faces the street. And she took me over to his desk there for some reason, maybe to show me where he does most of his work and how the carpet was so threadbare over there that . . . But that was where he’d done most of the work. So she said, “He’ll be in in a moment. And when you visit with him,”—she had two chairs sitting right next to each other—she said, “he is having a little difficulty hearing and he is beginning to slur his words a little bit, so be patient with him.” Well, so he came in and . . .

WILLIAMS: This was in the little library or study?

PETROVIC: No, this was in the front room. She had seated us . . . You know, I can recall that the two chairs were here. Mrs. Truman sat in the corner—that was one of the points I was going to make—across the room from us, in the corner. That was like the front door area right in that corner of the room—that would be the northwest corner—and I could see . . . So I sat there. He sat on my right and I sat right here—apparently that was his better ear—and then she sat across there and hardly said a word, other than I asked her about Margaret Truman, since she knew that I knew Margaret, and I said, “Send her my regards.” And then I proceeded to tell the president, presented him with the picture with all the autographs, and told him how his name was proposed and how it was received. [See appendix item 10.]

Interestingly, and this part I would want to let it be known after I pass on, that the response to his . . . Well, let me go back a minute and tell you what took place. And then remind me to get back to that. Sometimes

17

I’ll have about four stories going here.

But at any rate, so I visited with him about it, and then I said . . . Oh, when he walked in he said to me, “Well, I see you on television all the time. Every Tuesday”—court meetings were Tuesday—“I see you on television.” And I, being self-conscious about my large nose, I said to him, “Well, you probably noticed my nose more than you noticed me.” Just a dumb remark. And he said, “Young man, that nose is your distinguishing feature and you ought to be proud of it.” Well, that was the end of it. I mean, now isn’t that a marvelous way to make you feel at ease?

And then I asked him after we had discussed the sports complex and he . . . We didn’t get into a great detail, other than telling him how I’d proposed the name. And Judge Curry knew the family better than I did, actually. He could have proposed it as a presiding judge even and preempted me, but eastern judge and Truman—and Curry was very kind, and Charlie Wheeler certainly didn’t argue, to let me do it. He was in my district, in a sense.

So then I said, “I don’t know how you handle . . . I’m busy here as eastern judge,” because we had all these projects. The bond election passed, the largest bond election in the history of Jackson County, second only to the one that Truman passed that brought Jackson County’s roads second only to Westchester County in New York, which is the campaign issue we used. And I have all that campaign material. We used the Truman experience of having really done a great job on bonds and modernizing the county. And all the bonds passed, seven different issues. So I said, “I’m 18

busy as an eastern judge, as you would guess, with all these bond programs. How in the world did you handle the presidency?” I said, “I have great admiration for the way you conducted yourself with all the pressure of the things you had that were far more important than what I was doing.” And he said, “Judge,” he said, “you can only work so many hours a day, whether you’re here on the county court or whether you’re in Washington.” And he said, “I just made up my mind that if I was going to survive that I was going to make the best decision I could during the daytime, and when I went to bed there wasn’t anything I could do. And I learned to get a good night’s sleep. And if there was something I could change in the morning, fine; if not, it was a decision that I made.” And he said, “That’s the only way you’ll survive in politics.”

WILLIAMS: So he would call you “judge”?

PETROVIC: Yes. Yeah, and, you know, I just wanted to lay on the floor and say, “Please . . .” but . . .

WILLIAMS: What did you call him?

PETROVIC: I called him “Mr. President,” yeah. I testified one time in Congress before . . . It was an interesting . . . it might be relevant to this, or maybe not. Sometimes I wonder if you just want that information about the house and nothing else, but I can’t help but recall the awe in which the senate . . . Senator Steven Young of Ohio, who was getting up in years, was presiding over a hearing on the Little Blue Valley flood control program, which was our project. The lakes and the flood control was all a project of our administration. So I went to Washington a number of times, and in this

19

particular time testified before his committee, and Burch Bayh, I believe, was there. And so it was called “Squirting Truman.” Naturally, they wanted me to testify, even over Curry or Charlie Wheeler, because I was representing the Truman, I was eastern judge, and so on. So my testimony, which I have somewhere in my files, I started out by saying that I’m . . . I knew Steven Young liked Truman—I was told that—and so I said, “I’m Judge Alex Petrovic. I’m from Jackson County, Missouri. I represent the same district that President Truman represented when he started his life in politics, and I’m here to testify on behalf of this project.” And we wanted some big bucks at that time. And Senator Young, he said, “Excuse me, Judge Petrovic, do you have . . . Have you distributed your remarks to the committee?” And I said, “Yes, I have.” And he said, “Well, let me interrupt you a moment to say this, that the president I’m sure is behind this program.” And I said, “Yes, sir, he is,” something to that effect. And he said, “Well, anything that the president wants, I’m certainly going to look very favorably on it. As a matter of fact, he saved me from political defeat in Ohio when he came up here and campaigned for me a number of years ago.” And he said, “I want you to go home. When you go home, I want you to tell the president that this issue will pass, that Congress will give you this money.” We even had the money before the bond election. I mean, that’s unprecedented. And he said, “And I want you to let the president know that this will pass through this committee without any problem.” So I went ahead and read the rest of my testimony, which was just superfluous. When I left there, some of the guys, including Senator Eagleton was there at the

20

time and some others, sang to me, [singing] “I’m just wild about Harry . . .” And so that’s the way that ended. I just felt like I was . . .

And, oh, yeah, he interrupted me and he said, “You know . . .” He wasn’t too much of a student of political names and terms. He said, “You know, Judge, I always wanted to be a judge,” he said—this is Senator Young. And he said, “As a matter of fact, I would love to trade places with you right now if I could just be a judge.” Well, he probably assumed that I was a federal judge.

That’s the same kind of treatment I got at the Houston space center when I said, “Judge Petrovic.” The guy thought I was a federal judge, and I had the damnedest visit of the Houston space . . . particularly when I told him I was from Harry Truman’s town, because that would get you almost anywhere. The minute . . . no matter where I went during all my lifetime, after having been eastern judge, no matter where I went, in any introduction, when they found out I was from Independence, as they say, it’ll get you a lot better seat on an airplane. And I always received this admiration, no matter where I went.

I went to Montreal, Canada, on a tour to look at Plus-Vieille-Marie and to see whether or not we could have a railroad station under the Union Station, and I met the mayor of Montreal. And the minute I said I was from Independence, Missouri, and had the same seat that Harry Truman occupied, which was part of my introduction, man, the heavens opened for you, you know.

WILLIAMS: Well, we still have people that . . . they know that Harry Truman was a

21

judge, and they automatically think that he was trying criminals.

PETROVIC: Yeah, that’s the most often-asked question.

WILLIAMS: Do you have that problem?

PETROVIC: Yeah, at one time, you know, the eastern judge of the county court had some judicial functions. The last—and it was Truman—and I have several of his speeches where he had actually recommended to modernize the government. In our administration, we recommended that we go the charter route, and I read, much to the surprise of the people who thought this was some kind of New York or Chicago philosophy, I read without letting them know a speech that he made in 1929. I made several Xerox copies—I found them at the library—where he had proposed the same sort of reorganization of county government, moving all these offices in there. And that held me in good stead, again “squirting” Harry Truman.

I can’t recall what your question was. Oh, yeah, the judge. So people would say to me quite often, “Are you . . . Well, I didn’t know you were a . . .” People used to call me all the time and want me to try cases. I had a woman who called one time. It was my most sorrowful refusal. I had a tendency to take her up on it. She called me and she said she was in a bar and got kicked in the breast and wanted me to represent her. And I, for the first time, I wanted to go over and examine the injury and represent her, but decided not. And many people would call and want me to marry them, but always assume . . .

Well, those judicial functions were taken away gradually, and I think Truman cooperated with them, and gradually moved to another court,

22

so that the last remaining vestige of any judicial power on the county court, as I understand it, was sitting as a judge on the board of equalization adjusting properties, and that later was diluted in the charter. And then every year in the Missouri legislature when I was down there, there was always a bill introduced to do away with the title of judge and make them administrators and so on, as we did here. And the judges from the 114 counties in Missouri would come down there and say, “Look, the pay is terrible. The only thing we have is the lifetime title. Don’t do it.” And I used to belong to the Missouri Association of Judges, so then you’d have to explain to people, almost embarrassingly at times, “No, I’m not a real judge.” As a matter of fact, I did a political takeoff on that one time when we had a big Democratic rally. I pretended like I got a call from Hubert Humphrey, who I can impersonate pretty well, and to this day some people think it was Hubert Humphrey that I was talking to for this Democratic gathering. When I said—his secretary said, “Are you a judge?” I said, “Judge Petrovic calling.” And she said, “Are you a real judge?” See, I mean, I set that up. I had my secretary say “a real judge.” And I said, “Well, no, damn it. I’m not a real judge. I’m an administrative judge, but may I speak with Senator Humphrey?” And then he comes on, and I did his thing and they had it on the air. But that did cause a lot of confusion.

[End #4369; Begin #4370]

PETROVIC: There was a considerable criticism on Truman, the thing I wanted to mention, on the naming of the complex.

WILLIAMS: Is this the off-the-record part?

23

PETROVIC: Yeah. I’d like to go off the record because I have a letter in my file that the Kansas City Star told me they would give me a front page if I wanted to reveal it. It was an interesting letter that took place when I had proposed the name of it and I got the letter from Dutton Brookfield, who has since passed away, who passed a letter on to me that Jack Steadman had sent him, and it was from some “Mr. Anonymous”—he didn’t sign his name—criticizing my naming of it, you know, “spawning Harry Truman.” It made a very derogatory kind of reference to the Truman family, politicians, and so on. And using that, because Lamar Hunt did not want to have that complex named after Truman, because the Hunt family was kind of anti-Truman, anti-Roosevelt, anti-everybody except that John Birch group. And it infuriated me that they would oppose it. Whereas, on the other hand, Ewing Kauffman and the Kansas City Royals, and Phil Corey, who was my contact, a lawyer, they were all for it immediately. And I couldn’t imagine why they were saying this “spawning Harry Truman,” you know, and I just resented the way they said it.

So I dictated a letter, and my secretary wisely said, “Why don’t you wait until tomorrow morning and let’s read it again and see what you think,” because I unloaded on him. Well, then . . . And I kept thinking about it. The letter from Mr. Anonymous was dated before I made the speech, and I have that documented. So it occurred to me either through my secretary or just the two of us talking about it, so now I had Jack Steadman. He had composed this Mr. Anonymous letter, obviously, or somebody. And so I wrote a letter to him the following day.

24

And first of all, he didn’t write me. He wrote Dutton Brookfield, and I got a copy of Jack’s letter. So then I sent a letter back to Lamar Hunt in Dallas. I don’t know. I don’t have any evidence that Lamar was for it, but Steadman was his principal so I assume that he knew about it or Jack wouldn’t take such liberty. So I wrote a letter, “Dear Lamar . . .” and I mentioned this letter of Jack Steadman’s, and the Brookfield letter and so on. Well, knowing that if Lamar didn’t get a copy of the original, Jack would be embarrassed. I meant to do this. I meant to embarrass him by answering Lamar Hunt, a letter to Lamar Hunt. No, I sent it to Jack Steadman with a copy to Lamar Hunt. Well, the next letter I got from Jack Steadman . . . And I said, matter of fact, I said, “Mr. Anonymous . . .” and I referred to him as “the dumb Mr. Anonymous,” or something like that, because I knew if Jack wrote it that would also bother him a little bit, because I never did care for the guy. And I said, “You couldn’t have known at the date of the letter, because I didn’t make the announcement, proposal of the speech, of the naming of the complex until April . . .” so and so and so and so, “and I don’t talk in my sleep,” I said. So I found him in the lie. Jack Steadman wrote me a letter, “Dear Judge Petrovic: Ouch!!”—exclamation mark, exclamation mark—and apologized for that. So they were not for the naming of the Truman complex, the Hunt organization. I have to say “the Hunt organization” because it was Jack Steadman.

WILLIAMS: And they’re the Chiefs?

PETROVIC: Yeah, the Kansas City Chiefs.

WILLIAMS: And the Royals were very supportive.

25

PETROVIC: Oh, very supportive. Ewing Kauffman, I got a letter . . . And if you haven’t interviewed Phil Corey, here’s a guy that knows a little bit about everybody, and he’s a quality guy. He’s up in years, but I’m sure he might be able to shed some light on Truman. I don’t know, he used to work for the Star and he wrote an article, “A View from the Top,” or something like that. But he was a counsel to Ewing Kauffman during the building of the complex, and a very prolific man in words, wrote about . . . He wrote [not] the editorial . . . but the history of William Rockhill Nelson or something for the Star when they had their big issue. So he’s a writer and a very talented man who’s got a great thought process.

WILLIAMS: I’ve heard the name before.

PETROVIC: And he also did a . . . He was against Lee Bailey, F. Lee Bailey in this treasure trove somewhere in the desert, and this gold that was supposed to be buried in this mountain. He’s written a book about that. And he also wrote a history of Ringling Brothers, Barnum and Bailey, that they never allowed him to publish eventually. The family had hired him to do it or something, and then they rejected it.

WILLIAMS: Before we get off the subject entirely, is this the date of . . . ?

PETROVIC: Yeah, the event.

WILLIAMS: So the Sertoma Club banquet?

PETROVIC: Of Independence. Yeah, it was an installation banquet in which we made him man of the year, the Sertoma Man of the Year.

WILLIAMS: Is this for the Independence chapter?

PETROVIC: Yeah, and later on it was picked up by the international . . . And when they

26

had their convention here, we . . . There was a picture of Truman and myself that they blew up for that, and that was to welcome them, showing Truman supported Sertoma.

WILLIAMS: This was April 10, 1962. Could you identify everyone in the picture so we’ll have that on record? [See appendix item 11.]

PETROVIC: Well . . .

WILLIAMS: You’re there at the far left.

PETROVIC: Yes, starting at the left, I’m at the left, then the president, and Noel Fields, and my wife, and Mrs. Truman . . .

WILLIAMS: What’s your wife’s . . . ?

PETROVIC: Her name is Fran. And then this is Mr. and Mrs. Cass Curan, C-U-R-A-N. He was a Kansas City . . . member of the Kansas City club, which chartered us.

WILLIAMS: Well, let’s change the subject a little bit. You said that you went to high school with Margaret.

PETROVIC: Mm-hmm.

WILLIAMS: Could you talk about the contact you had with her as . . . I guess you were teenagers.

PETROVIC: Yeah, I went to junior high with her, and we were in a school play, and she portrayed the part of an old woman. And interestingly, that portrayal was not too far different than what she looks like today. And I have a picture of that that I think I gave to the library here. It was a school picture on the set, and I was sitting on the arm and Margaret was next to me. It’s a play called “For Pete’s Sake,” and it was in junior high school in Independence, and

27

that was . . . It’s now part of William Chrisman. It’s right across from the Memorial Building in Independence, that school there.

WILLIAMS: Palmer?

PETROVIC: Yeah, Palmer. And I had not seen her since then. I reminded her . . . Rose Conway set up a meeting with Margaret and myself, the first one, which was about seven, eight years ago, and when she said she would like to see me after I had made the request. So I came over and reminisced with her. I remember holding her for one guy on the set, one of the kids who wanted to kiss her—you know, just typical kid stuff—and she reached over and got a spoon, a stage spoon like you hang on the wall, a plaster of Paris spoon about that big, and either hit him or me, and I don’t recall which. I think it was him because I was kind of holding her, and Billy Jones wanted to kiss her. And Billy Jones was just one of the guys on the set that played a fellow named Mugsy Mugglethorpe—I will never forget that—but that was my connection. Margaret had not . . . She had forgotten about it. We tried to get her to come to the reunions but she never did, of our class reunion of ’41. She would have graduated with us had she been here. And the girls that lived across the street from her, the Bush twins, did you ever talk to the Bushes?

WILLIAMS: I talked to Elizabeth.

PETROVIC: Yeah, the survivor? They were very close. And then Dorsy Lou Compton. Have you talked to her, Dorsy Lou?

WILLIAMS: Yes.

PETROVIC: We just had our fiftieth reunion of that group, and so all that group have .

28

. . Every time we’d have it, I was master of ceremonies. I’ve been master of ceremonies at every one we’ve had yet, and we’ve had a ball. And they all tried to get Margaret to come in the past, but just gave up on it since she really had no interest in meeting with us again, which was obvious.

WILLIAMS: I was wondering if she came back to that reunion. Usually the fiftieth one is special.

PETROVIC: Yeah, we thought, but we . . . We were just disappointed in her and the fact that she wasn’t here very often when her mother was ill. But I had a nice visit with her and she certainly . . . We met in the library, in the president’s . . . that receiving room he has back there, and had a nice chat. And I never sensed any reason for her, you know, to get up and make it quick and get it over with and let’s get out of here.

WILLIAMS: What was she like as a girl?

PETROVIC: She was a very friendly person that . . . I don’t think she flaunted her position, as a senator was a pretty big position, but she mixed well and there wasn’t really that . . . I wasn’t aware of the fact that she thought she was better than anyone else. And I was really . . . We were not wealthy. I mean, when I went to Dorsy Lou Compton’s house, Polly Compton’s house, you know, the only reason I joined ROTC is because I couldn’t afford . . . my mother and father couldn’t, with all the family, and my father was a struggling immigrant who immigrated to this country. I had enough to eat, we always ate well, but we had a big house that we nearly lost. But I was certainly not a very . . . I mean, we were not poor, but we certainly were lower middle class. And to have the opportunity to go to Polly Compton’s

29

house on that third floor where they had that big dance floor up there and to ride in this 1941 new Oldsmobile Hydromatic was the thrill of my life for a guy who had a . . . You only needed one hook in our house to . . . put your overalls on one, because you were wearing the pair of pants that you had to go to school in, or the uniform. So I was always happy that I was accepted in that group.

WILLIAMS: So you did mix with that neighborhood group?

PETROVIC: Yeah, the Bush twins were good friends of ours in school. And I was kind of an entertainer, more than I was worried about my grades, and was in a lot of school plays, and that’s where I got my little notoriety and kind of acceptance by being in the school plays with some of the people, the Adamses and the Bush twins and so on. But I never met Margaret outside of school. I never had any contact with the Truman family, other than to see them at some functions. And when I was county judge . . . And as a matter of fact, when I was in the Missouri legislature, when I requested the president to write . . . Rose Conway to write to Chairman Tom Walsh on my bill, which was in that manual, that he did that very cheerfully. I could have talked with him personally, but I knew it was the Hoover Commission that . . . The bill was introduced under the Little Hoover Commission, and certainly that was saying my position was to support or to use the vehicle that Truman had provided in the Little Hoover Commission. And then I asked Thomas Hart Benton to write a letter, and then Phil Brooks here was very supportive of it. They had tried to pass the bill before, so my bill was in the interest of the archives, the National Archives. My brother-in-law

30

worked for them, and I even got a letter from Ernest Posner who was then the head of the archives, if I remember.

WILLIAMS: How long were you in the legislature?

PETROVIC: Two terms. Four years.

WILLIAMS: What years were they?

PETROVIC: I was elected in 1962 and served through ’66.

WILLIAMS: As a Democrat?

PETROVIC: Yes. Oh, yeah.

WILLIAMS: Always a Democrat?

PETROVIC: It would be a sin to be otherwise. [chuckling]

WILLIAMS: In Jackson County.

PETROVIC: And Sugar Creek. It was an interesting place. Sugar Creek is virtually all Democratic. The only avowed, known, admitted Republican died a few days ago, and I went to his wake. That was Pete Saxton. And Saxton used to take a lot of pictures, and he’s got a pretty . . . He’s not a native of Sugar Creek, but he maintained his political allegiance to the Republican Party just so that we could all kiddingly say that we had a two-party system in Sugar Creek. But it was predominately Democrat. And when Bobby Kennedy came here and I brought him up to the library, along with others and the mayor and so on, and Sermon was here, and Dick Bolling and so on, Truman said to Bobby Kennedy . . . You know, we wanted him to come down to the big celebration. We had the second largest turnout of Democrats for our annual Fourth of July rally than any place in Missouri, except Springfield. We used to attract 5,000 people there. And so we tried

31

to get him to come back there, and he said, “You don’t need . . .” Well, I just invited him, and he said, “You don’t need me in Sugar Creek.” He told Bobby Kennedy, “Sugar Creek is solidly Democratic. You won’t have any problem there. You’ll need me to work in southern Missouri where these ‘tail-twisting Baptists,’” as he called them, “live.”

So we used to have large rallies, and I did another impersonation that got me some notoriety of Earl Long when he visited Truman up here. Almost simultaneous with that we had our rally. So I had a fellow, a friend of mine, dress up like Earl Long might have looked—I didn’t meet him—and we put on a show as if Earl Long had just been at the Truman Library and visited us here down in Sugar Creek.

WILLIAMS: When did you take a real serious interest in politics?

PETROVIC: It was in 19 . . . I didn’t really—I was kind of pushed into it. I was sitting in a dentist’s chair with a rubber dam in my mouth getting a gold filling, when the dentist had a call from Independence from a fellow named John Hayner, who wanted to file me for state representative. And I didn’t, to be honest about it, know whether I served here or in Washington. But I mean, I was always the master of ceremonies of all the events in Sugar Creek. That was my first interest in politics was being master of ceremonies, to go back to answer your question more accurately.

So I was master of ceremonies every year, and everybody knew me. Pretty soon somebody said, “Hell, you’re so well-known, why don’t you run for something?” And I declined. Then I got this call, and they did file me. I couldn’t talk. I just totally . . . “uh-huh,” you know? Then I filed and

32

then ran back home to find out what a state rep does. So that’s my first . . . There were nine guys in the race and I was put in there as a bargaining tool, and after it was over with, everybody started peeling off. I had been pretty well known in Independence with the Sertoma Club and all that, and so I was elected over an RLDS candidate, much to my father’s surprise, who never thought that a fellow who lived in Sugar Creek, which he always criticized me for moving to Sugar Creek, “should have stayed in Independence,” he said—would run in the world headquarters of the RLDS church as a Catholic from Sugar Creek. I mean, I couldn’t have had any more sins compiled than that and still won. And my father, when I won, the night he looked up in supplication and said, “Oh, my God, you won.”

WILLIAMS: What was your district? What territory did your district cover?

PETROVIC: At that time it was a little larger than it is now. It went from the Missouri River here out to like Twenty-third Street, over to Blue Ridge, the Kansas City side, and then out east to about 71 Highway.

WILLIAMS: So basically the heart of Independence?

PETROVIC: Now it’s cut in two now. That district was made . . . There was a fellow named Homer Clemens—he was a school superintendent—who also knew Truman, who just recently passed away, but our two districts were split in two. Now, Carol Roper still has this area, but they added another representative out east.

WILLIAMS: Was it an advantage in the legislature to represent Harry Truman?

PETROVIC: Sure was. Sure was. And particularly in my bill. My bill had failed before.

WILLIAMS: Why were you so interested in the records? 33

PETROVIC: Well, just through what Truman did. I had been reading about it, and my brother-in-law came over to the house one day saying that . . . He was with the National Archives.

WILLIAMS: What’s his name?

PETROVIC: His name is Al Petrovsky, as a matter of fact. So he was head of the records center in St. Louis, and so that was his interest. And they had tried to pass it. So, through a friend of his in Kansas City who ran the Kansas City records center, they said, “Why don’t you get your brother-in-law to introduce the bill in behalf of the archives?” The National Archives was really interested in getting a records act. So he did all the graphics and the statistics, and I went through the committees and so on, and there just wasn’t that much interest. But after he had prepared me so well in the material that I had—and it was so overwhelming—and then it was my idea to get Truman, and then Phil Brooks of course helped, and then Thomas Hart Benton. And it was sort of a celebrity bill by the time it was over with, with Truman, you know.

The chairman of the committee sat next to me in the house, and his name was Tom Walsh. He was a tough labor guy from St. Louis. Scared me to death when I first sat next to him. Another kind of a Jimmy Hoffa type, and just used to intimidate the hell out of me because I was just a little virgin down there and here was a guy that controlled the St. Louis delegation. And he said, “I’ve got some bad news for you, Petrovic.” And I said, “What’s the matter?” And he said, “On your damn bill.” I said, “What’s the matter?” and I was just taking everything so seriously. He said,

34

“Truman wrote a letter and was against it.” I said, “Truman wrote a letter and was against my bill? I can’t believe that!” He said, “No, damn it, I’ve got the letter. I’ll show you in my office.” So, I mean, I was white. And I went into his office, and he just manipulated me like a little puppy and said, “Here’s the letter. Look at it.” So I’m reading this damn thing, and it was all positive. [chuckling] That was the letter that was in there. So then he looked at me and he said, “You can have the letter, too, because I know you would want it.” So that’s the way that ended. And it passed over . . . It went through the senate; and with the presentation, everybody was jumping onto the bill.

WILLIAMS: Why would anyone be opposed to such a bill?

PETROVIC: Oh, because of the . . . Interesting. A fellow named Brownlee, who was then head of the state historical society, Richard Brownlee, everybody wanted . . . The lawyers were worried about what’s going to happen to the legal stuff, you know. There’s one thing that you learn down there, that if the lawyers are against it, they’re going to kill it. Well, here was Brownlee in the state historical society wanting to be sure that none of his records were going to be tampered with. Everybody was worried about their own turf. And when in turn, following the guidelines of the Hoover Commission, the Little Hoover Commission, it was a clean thing. But everybody worried about their own little records getting looked at, see? Everybody was worried.

Interestingly, that bill has saved the state of Missouri, very recently by the admission . . . We put it in the secretary of state’s office. That was

35

our option to where we think it ought to go. Well, since he’s kind of the historian of records of the state and so on . . . And Kirkpatrick was delighted to get it. He was worried that I was going to ask him to hire my brother-in-law, because he . . . He said, frankly, he was very nervous about taking pictures and getting involved in it because he thought I was trying to get my brother-in-law a job in his office, which I wasn’t. But it saved the state of Missouri hundreds of thousands of dollars in just getting . . . knowing what to get rid of. And we had enough file cabinets. The final testimony is that if this bill passes, the file cabinets that we have right now, the surplus file cabinets would stretch from Jefferson City to Ashland, Missouri, which was like fifteen miles. They never ordered file cabinets for ten or fifteen years after. There was a moratorium on file cabinets. We had file cabinets all over the place.

WILLIAMS: So things went to the dump.

PETROVIC: Went to the dump. And, you know, most people, their idea of records management was to fill a cabinet and move it over to another building, and then let it . . . And nobody knew what was in it. The incumbent would be gone, and so it was just nobody knew anything. So the whole bottom of the Missouri legislature, of the capitol, was reclaimed through my bill. That whole area was filled with records. When I was climbing on those boxes, that’s where they were. The only records management we had in the state of Missouri was to burn a building down. That was the only way you could get rid of records was to burn them through fires. [See appendix item 12.]

WILLIAMS: So this set up the whole procedure? 36

PETROVIC: Right. Now they’ve got a new one, and I was pleasantly surprised because I didn’t know he was going to feature my bill in the “Blue Book.” But, of course, with the new records center down there . . . And then we carried that, not only that, but when I became a judge of the county court, we started a records development center here. And that’s when we ran across Truman’s bankruptcy proceedings, which was kind of an embarrassment to the family, as I later learned. I need to go off the record here, too. A rather interesting thing . . . How much do you interface with the library?

WILLIAMS: Me personally?

PETROVIC: Yeah, or your whole division.

WILLIAMS: Only as necessary. [chuckling]

PETROVIC: Okay. Well, this has to be off the record. Let’s shut the machine off for a minute. [tape turned off] I’m sure you’ve got other things to do, and I have to be home about a quarter till or a little bit before.

WILLIAMS: Okay. I need to ask you about the house. When was your first visit to the Truman home?

PETROVIC: The first visit was to . . . I had represented a company that manufactured plastic wall tile, and there was an installation there and I wanted an excuse to get in the house. So the fellow that installed it was a friend of mine who bought his material from me, so . . . His name was Gene Sanders. He’s since passed away. He installed it, and I went up and inspected it, so-called, and that had to be . . . I can’t be specific, but it had to be in ’48, ’49, or ’50, something in that area. And never saw the family, to my recollection. They weren’t there. I was just kind of ushered in and . . . It was very informal. 37

Then, after the sports complex visit, advising the president and gave him the picture, which he prominently displayed over there in his private area, then I was there at the request or the urging of Ray Zackovich, who wanted me to bring some . . . he said some Polish sausage and cabbage rolls from the Sugar Creek event that we had. And I delivered them there and met Mr. Truman on the back porch, and Mrs. Truman, and their maid, if I’m not mistaken. And I later learned that it was too rich for him, but they ate it and enjoyed it. Ray Zackovich took me there probably two times through the back door into the screened-in porch. And then another time, I can’t recall what the situation was, but I was shown his study a little more in detail. That might have been at the same time that I visited the president on the sports thing.

WILLIAMS: Back on the tile, do you remember what kind of tile was this?

PETROVIC: It was plastic wall tile. [See appendix item 13.] The company was Injection Molding Company, and that’s who I represented. They were an injection molding company. We made wall tile that was distributed all over the United States, and I was the sales manager of the company.

WILLIAMS: Do you remember the color or anything?

PETROVIC: No, I want to say that it was a red . . . Have you seen it? Is it a red marblette, I think, but I’m not sure. I could have been . . . Why that sticks in my mind, it was a very popular color, but I can’t tell you for sure.

WILLIAMS: And this is the upstairs bathroom?

PETROVIC: Yeah.

WILLIAMS: It’s kind of a blue color now. I think they remodeled it.

38

PETROVIC: If it’s plastic, it was a flat-looking plastic tile, but it was kind of revolutionary at that time, because you could put it on the wall, stick it on the wall, as opposed to tear the wall down and lay the cement and put your ceramic tile. And it was very fashionable, very popular at that time as a substitute because it didn’t carry a lot of wall load, and maybe that was a consideration that Mrs. Truman had.

WILLIAMS: We’re having plaster problems up there, as a matter of fact. So this was a brief visit?

PETROVIC: Just an inspection, and I don’t even hardly remember how I got upstairs hardly, but . . .

WILLIAMS: And the Trumans weren’t there?

PETROVIC: If they were there, I didn’t notice them. I’m sure somebody was there.

WILLIAMS: And this was when he was president, so the Secret Service would have been around?

PETROVIC: Yeah, it seems to me. I just don’t remember much about that, other than visiting. Yeah, it would have to be. Maybe he wasn’t there. Yeah, maybe no one was there. That was probably the case, really, now that you . . .

WILLIAMS: Did you ever hear through Mr. Sanders what the reaction was from the Trumans?

PETROVIC: He told me that they liked it very much. He was a real rotund, jolly guy that was kind of . . . everybody liked him immediately. But he was telling me that there was some satisfaction and they liked it, and he had dealt with them in picking the color out and so on.

WILLIAMS: Did he do work with them before? 39

PETROVIC: No. I don’t even know how he got the prospect. It might have been through another company that he worked for, but he’s the one that did the job.

WILLIAMS: The second visit was for the sports complex?

PETROVIC: Yeah.

WILLIAMS: And what year was that?

PETROVIC: That was in . . . That had to be after the bonds were passed. I would say that is either ’69 or ’70.

WILLIAMS: So Mr. Truman was getting on in years.

PETROVIC: Yes.

WILLIAMS: Because you said Mrs. Truman . . .

PETROVIC: She sat over there in the corner and just let us visit. I mean, it was like my mother would have done. I mean, if the two men were going to visit, she didn’t interject herself. She just sat over there with her hands folded and, you know, listened, but let us . . . And I think she realized that this was quite a thrill for me, but it wasn’t any federal case or anything, she just let me go.

WILLIAMS: Was this the big room with Mr. Truman’s portrait in it?

PETROVIC: I can’t remember what the room looked like. I was just too geared up on what I was there for, and I was excited.

WILLIAMS: You said it faced the street.

PETROVIC: Yeah.

WILLIAMS: Delaware or Truman?

PETROVIC: Yeah, Delaware. It faced Delaware.

WILLIAMS: Did she offer you any refreshments or anything like that? 40

PETROVIC: She might have asked me, and I don’t recall. I don’t think so. I just think it was . . . And there was no time limit. I was there for thirty minutes and visited, small talk.

WILLIAMS: She warned you that he was a bit hard of hearing and . . .

PETROVIC: Yeah, she said, “He shuffles a little bit and uses his cane, and he’s not too sure of himself, but he knows . . . He’ll know what you’re talking about if you just kind of get next to him and kind of talk in his ear a little bit more!”

WILLIAMS: Did he seem better than the picture she had painted or about the same?

PETROVIC: He seemed alert. I never sensed at all . . . And when he pointed to me and said, “That’s your distinguishing mark and you ought to be proud of it,” I knew that was the Truman that I had seen before and talked with. I’d seen him over at the library half a dozen times. But he definitely was slowing down, but was still alert.

WILLIAMS: So you went from the state legislature directly to the county court?

PETROVIC: Right.

WILLIAMS: In ’66?

PETROVIC: Yeah, elected in ’66.

WILLIAMS: And you were a county judge until . . . ?

PETROVIC: Nineteen seventy, through 1970.

WILLIAMS: And is that when the present system of county government was established?

PETROVIC: A year after that . . . It was established during our administration—that was one of our campaign planks—and after that it . . . The charter came into effect, I think, about a year later, and Joe Bolger served as the last eastern judge of the Jackson County Court. We were up in front of the Truman

41

home when they wanted to reduce the size of the legislature from fifteen to about eleven, what it is now, and it was essential that it was done . . . That was part of the plan, to do it in front of the Truman home—I don’t know, I guess just to focus on it. Truman, when we proposed the county charter, our political opponents were in control of the governor’s office, and they had a chance, our opponents, through Governor Hearnes, had a chance to pick the people on the charter. Here it was our product, but the governor . . . our enemies were the ones who actually had the charter hearings, Harold Friedkin and a number of others. We lost total control of it by virtue of the governor’s office, who appointed the people to hear it and the circuit judges. So I went over and testified, and I had . . .

And I wanted to talk with Truman, so I talked with Truman about . . . I think Curry and Charlie Wheeler and I visited with Truman and asked him what size of court would he recommend. We knew it was going to be larger, but there was some reason to maintain a three-judge court, at least in the minds of people more now than ever before. And so I asked the president what did he recommend, or did he have a suggestion. Among other things, we talked about the other bond issues. That’s a specific on the court. If the charter goes through and we accept these recommendations to shorten the ballot according to the plans that you laid out years and years ago, and I reminded him of a speech he made at Colbern Road, a speech in which he had suggested this. I said, “What size of the county court would you think would be ideal?” And he said, “I’m not going to tell you that.” He said, “I don’t think that’s any of my affair, but I would suggest to you to

42

keep it as small as possible. Don’t let it be so large that it’ll be another city council. Because you’ll have all these people representing every interest, and it becomes neighborhood. Then it’ll talk about sidewalks and curbs and streets.” And he said, “The county court should be a fast-moving body. It should be able to make intercounty, inter-city, interstate compacts, and it should be able to move fast, and if it’s too large it won’t.” Well, he didn’t tell me a number, so I had proposed in front of the charter from five to seven people maximum. After looking at the nationwide system of county governments, that seemed to be reasonable. Well, what did they do? Fifteen people ended up on there. Everybody had their two bits, and indeed it became, as I’ve often said since then, another city council. And that was the reason why I was invited to speak on it again, since it was a product of our administration, and so we stood in front of the Truman home. I don’t know whether . . . who suggested that, or whether I suggested it or said it would be . . . why don’t we do it in front of there. I think it was the committee. And so we stood in front of the Truman home and, as that as a backdrop, spoke from that point.

WILLIAMS: And that was the recent shrinking?

PETROVIC: Several years ago, yeah.

WILLIAMS: From fifteen to eleven?

PETROVIC: Maybe eight, nine years ago, seven, eight years ago. Yeah.

WILLIAMS: So you’re one of those rare politicians who kind of created yourself out of office in the new system?

PETROVIC: Mm-hmm, yeah. Matter of fact, everybody thought I was going to win, but

43

I did a couple of things that didn’t fall. Curry left and then everybody thought I was going to win, and the other guy worked a little harder, and then I fired a couple of people and did not kow-tow to Harvey Jones, who’s a good friend of mine, and he worked against me and put Bolger up.

WILLIAMS: So you did run for the county—

PETROVIC: I ran my third term and was defeated, uh-huh.

WILLIAMS: But you didn’t run for the county administrator or county executive, I guess is what it’s called?

PETROVIC: No. I did file last year and got out on another fluke.

WILLIAMS: I have a few more questions if you have time.

PETROVIC: Yeah, I’m just right over the hill, so another ten minutes if you want to go ahead and shoot for that.

[End #4370; Begin #4371]

PETROVIC: Leslie, you do a good job. [chuckling]

WILLIAMS: You mentioned when we were off the tape, you described Rose Conway. Could you describe her again and your relationship with her?

PETROVIC: Yeah, Rose Conway, in my opinion, is probably the almost perfect kind of executive secretary that you would want. She was extremely protective of the president, in a way that wasn’t obnoxious. She was very cooperating, and I always felt that when I would ask her a question that would involve the president, that she always prefaced it by saying, “Now, I don’t want you to think that the president said this, but here’s the way I kind of see it . . .” But always afforded me, and I’m sure others, an opportunity—but I can’t speak for them—to bring people in the library who had a serious interest.

44

Or she would . . . Just like the Paulsen deal, she didn’t have to paint me a picture. I knew exactly that the president didn’t want to see him. He probably was peeking out of the house when we were there. And Paulsen knew it. Paulsen felt very uneasy. He knew he had blown it. And that was vintage Truman.

But Rose Conway, I visited with her many times, and she would call me if she wanted me to do something for her. And I can’t recall what it was, but we always had a . . . just a kind of a . . . you could just come in the back door and visit with her. She’d always give me time. She was a most gracious lady. I never, ever expected her to write a book. Now, that’s the kind that you dream about. But she was a rare person.

WILLIAMS: She wouldn’t even give an oral history to the library.

PETROVIC: Is that right? God.

WILLIAMS: She took it all with her.

PETROVIC: She took a ton. I can remember one incident that I need to go off the record on the thing, and that was when I was in there one time and somebody from the Jewish community had called and wanted to donate an ambulance for Israel and wanted Truman to have his name on the side of it. The Jews just worked him to a lather, I guess. [chuckling] But anyway, the conversation went something like this: “Well, no, I’m sure the president in the past hasn’t done this, and I’m sure he won’t agree to having his name on there.” And then there was this other conversation, and she said, “Well, I’m telling you that I just don’t think it would be worth your while to talk to him about it.” And it went on again, and finally . . . finally, it got a little worse, and then

45

finally after . . . she just finally said, “Well, I’ll ask him, but I’m sure it will be negative.” So then that conversation ended. She looked up and she said, “Mr. Truman never said this,” made that preface again, “but they either want to love you or want to kill you. There’s no in-between.” [chuckling]

WILLIAMS: So she mediated a lot of things like that?

PETROVIC: Yes. Oh, yeah. I just think she was a great mediator. I think that’s what made her more exceptional, because I think he relied on her to clear out . . . He was so accessible. He was so accessible, and I never really understood how he could have the patience to sit there when I’d march someone in, an in-law or a friend. But she would screen it, and he seemed to rely totally on her judgment. And it was she that had this . . . She just resented this infringement on the family. I think she held them so dearly and must have had such a relationship that she was the guardian angel of the Truman personal side. And if Rose Conway told you something, that was it. And she was just as good a person as I’ve ever known.

WILLIAMS: You knew you didn’t have to second-guess her judgment?

PETROVIC: Exactly. She said it, that was it, and . . . But she made him so accessible, so apparently he didn’t mind either. I think he rather enjoyed it. And he, a number of times, he took me into his . . . I visited with him one time, and I don’t know what the occasion was but it wasn’t anything big. I just probably was in there and he was in there and I would see him. And he took me into the back room and showed me . . . Oh, yeah, my state records act. And it was just conversation that he knew it passed, and took me into the little side room where he had . . . and showed me letters from President

46

Hoover. And he said, “No one ever paid any attention to Hoover.” And he said, “And when I gave him that job of heading that commission”—the letters have been public, I’ve heard them—and he told me that he was so appreciative. He said, “I’ve learned to admire the man.” And they had a great relationship. And he showed me a letter that Hoover had written him, two or three letters. And I asked him about certain stuff that he had on the walls here, you know. He made it a point to show me he had the Sertoma award hanging in that area—not public, but in his own area.

WILLIAMS: You mentioned as an eastern district judge for Jackson County that one of your duties was to show people around Independence, I guess.

PETROVIC: Mm-hmm.

WILLIAMS: You’d bring them to the library, but would those stops ever go to the Truman home after Mr. Truman stopped coming here?

PETROVIC: Oh, yeah. The interesting thing about it, people would come in that office knowing that his office was in the county court building—I mean, in the courthouse. But never realizing that that was as interesting a part of the tour as anything. And I’d say, “Do you realize . . .” You know, “We want to see the Truman home. Where’s the Truman home? And where’s the library? And can you give us any information on that?” And some of it was just people walking in. And I’d say to them, “Do you realize you’re standing in his office?” “Oh, my God!” I mean, it was almost hallowed ground. I could never understand why that wasn’t more part of the itinerary, because that’s where the nuts and bolts was, at least outside of his home, which was more of a sanctuary to him. But they were always happy.

47

And the Koreans just loved him. I brought a number of Koreans through here, to take them over. As a matter of fact, I took a prominent doctor from Japan through here during the last ten years who . . . I was told through the people that asked me to take him through—he is the one that pioneered arthroscopy—to avoid the atomic bomb display. And damned if I didn’t . . . I knew where it was, but I didn’t know they’d moved it. And as I rounded the corner, thinking I had avoided it, there it was bigger than hell. And of course this Japanese, I figured if he was going to say anything, I’d tell him, “We didn’t start it.” I applauded Truman for dropping the bomb. But the Japanese handled it very well. Then we used our helicopter two or three times in other events to fly over here and photograph this place for Ben Zobrist.

WILLIAMS: Would you just then take these people by the Truman home? You wouldn’t arrange a personal visit?

PETROVIC: Many times I just took them, yeah. I never, ever imposed on the family there by making a federal case. We’d just pass by it. But I took them through my courtroom. And then those people . . . There were some from Africa who came through here, Malawi, and brought him over here and introduced them to the president from time to time. And there was an insurance executive that was doing something who wanted to meet Truman, and Truman came out and took pictures with him. I have that in my files at home, from Franklin Life Insurance Company. And then the Bobby Kennedy thing was my most noteworthy kind of visit. And all those pictures have been turned over to them.

48

WILLIAMS: So Bobby Kennedy came up to the courthouse?

PETROVIC: No, just to the back room here, the president’s.

WILLIAMS: And you were . . . ?

PETROVIC: And I was part of the entourage there. The only one with a camera. The only one with a camera, and it was out in the car. And I said, “Oh, my God, here I am with some history here,” and I wanted pictures, and finally I just said, “I’ll do it,” I was just thinking to myself. “Mr. President, excuse me, but I have a camera in the car,” and there wasn’t any press there, “May I go out in the car and get it?” And he said, “Sure.” So I just went through the crowd, pushed through there and all the crowd in the back, and got the camera, walked back in and took pictures, and didn’t have a soul take a picture of me. And everybody else just loved the pictures. I mean, I had an affinity for doing dumb things, you know. That was one of them. [See appendix item 13.]

WILLIAMS: That’s the way I am.

PETROVIC: But those are very precious to me.

WILLIAMS: Could you talk a little bit more about your visits with Ray Zackovich?

PETROVIC: Ray Zackovich? Yeah.

WILLIAMS: You arranged . . . You said that you got . . .

PETROVIC: Well, a couple of times he took—

WILLIAMS: . . . access to the study of the house.

PETROVIC: Yeah, matter of fact, I think he was the one that took me in and showed me where . . . the first time, or to more detail, where the president did his work every morning, and I was amazed at how threadbare the rug was, where you

49

could just see where he sat. But Ray seemed to have . . . Ray was a gutsy . . . a gutsy Secret Service man who took liberties far beyond . . . I think, if you’ve met him . . .

WILLIAMS: I’ve talked to him on the phone.

PETROVIC: He’s just a gutsy guy. I just wonder how he lasted so long. I don’t want that in the . . . You might want to delete that, too. But he just seemed to be able to do anything he wanted over there. And so he’d call me up sometimes and [say], “Let’s go see the president today.” And I’d say, “What have you got going on?” And he’d say, “Well, get some Polish sausage down there at the thing and let’s go over.” My wife made some Polish sausage and cabbage rolls, and we took it up there one time with him.

WILLIAMS: Did you know he liked . . . used to like those things?

PETROVIC: Well, Ray would say it, but you couldn’t tell whether Ray knew any more than . . . But I learned that it was too rich for him. I think Mrs. Truman told me that it was pretty rich for him, he was trying to watch himself. And probably so. If you haven’t tasted that stuff, it’s just like getting a shot of Shlivowitz without thinking it was some lime juice or something. [chuckling]

WILLIAMS: And you said you sat out on the back porch?

PETROVIC: On the back porch, and just kind of small-talked for a little bit, and then we left.

WILLIAMS: He obviously knew who you were?

PETROVIC: I was taken in by a Secret Service car. Yeah, well, he knew who I was, sure. But Ray . . . Sometimes I was a little bit embarrassed by it, because without

50

any protocol at all, here I come riding in there and come up to the back door and say, “Here . . .” you know? But Ray was gutsy. He’s the one that bawled me out for not letting him know and then taking me personally to visit the president at the time of the wake here. And that wasn’t my idea.