Last updated: July 18, 2025

Article

World War II Submarines in the Aleutian Islands

George Herold

US Navy/Naval History and Heritage Command

Finback

The USS Finback, a Gato-class submarine, was laid down in 1941 and commissioned in 1942. She patrolled around the Aleutian Islands, Taiwan, Rabaul, Japan, Midway, Marshall Islands, Australia, Java, Caroline Islands, Mariana Islands, and other locations. The Finback is probably most famous for rescuing the future 41st President of the United States, George H.W. Bush.

In the Aleutian Islands, the Finback attacked two destroyers on July 5, 1942, conducted reconnaissance around Kiska Island on July 11, and did a surveying operation on August 11, around Tanaga Island. After his submarine, the S-27 sank, George Herold was transferred to the Finback. He recalls, “Well, right away, we continued to patrol on the Finback, which was … they were patrolling the eastern Aleutian Islands - out by Adak, Atka and all that out there. And we … we made one attack on a Japanese destroyer that was not a success – we didn’t get any hits. And we were bombed by an aircraft once or twice - that’s all in the ships log. I could give you the date if I looked it up. But, we were bombed by aircraft, and we made an attack on one Japanese destroyer which was unsuccessful.”

It was on the Finback’s 9th patrol off the Palau Islands that it was able to rescue multiple downed pilots by providing “lifeguard duties” at the beginning of the Marianas Operation. One of the pilots rescued was Lieutenant (junior grade) George H. W. Bush. George Herold wasn’t on the Finback during this patrol, but he heard about it later from his fellow submariners:

“So George Bush … now, I wasn’t there when he was picked up, this was in September of 1944 when they picked him up. And they also had picked up four other flyers. And George Bush … you could, evidently you could tell, was a Joe College type – [he] came from a higher plane or family - like that. And he didn’t mix with the rest of the crew. And it’s tough not to mix with the rest of the crew if you’re on a submarine, because you’re always rubbing elbows with somebody - it’s so small. But, he didn’t, he wasn’t a mixer. The other four guys, they mixed well with the crew – they came back aft to the engine room and the motor room and the torpedo rooms and talked, talked to the guys - like that. But, George Bush was a, was just the opposite. Now, [Laugh] I could be talking like a democrat, so I’ll, I’ll let up here like that - that’s just my impression, I wasn’t there, I ‘m just getting it from the guys that were there. At that time, I was on another submarine called the Picuda [USS Picuda (SS-382)]. And we were doing our thing on that boat.”

The USS Finback made 12 wartime patrols before being engaged in training student mariners in New London, CT. In 1950, the USS Finback was declared inactive and unfit for further naval service. As the Naval History and Heritage Command wrote: “The boat that received 13 battle stars for her World War II service, had nine of her 12 war patrols designated as “successful,” had been credited with sending 59,383 tons of Japanese shipping to the bottom, and saved a young naval aviator who went on to become Chief Executive, was stricken from the Naval Register on 1 September 1958.”

US Navy

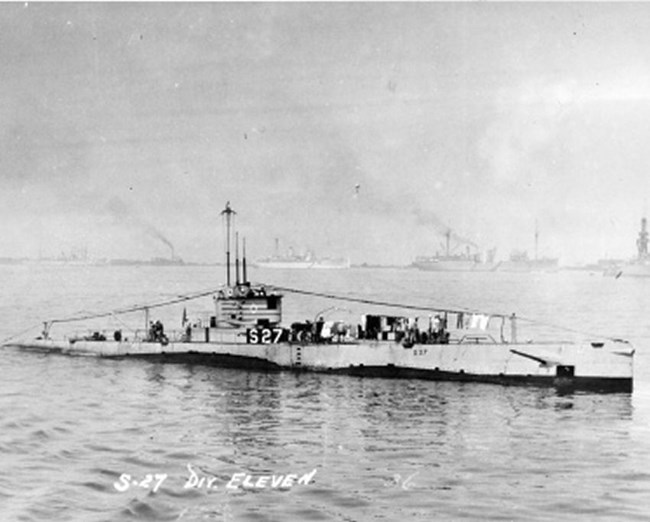

S-27

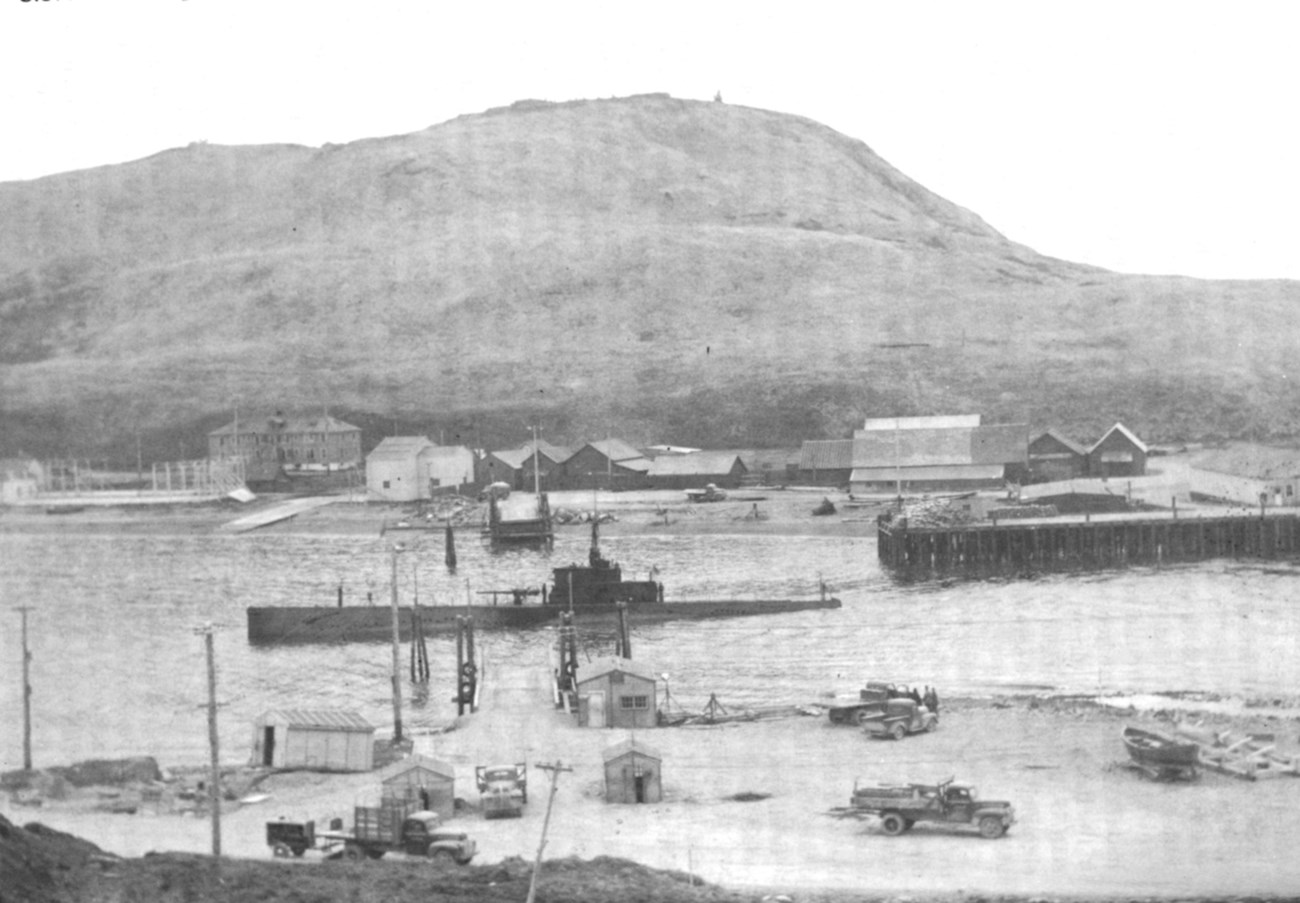

S-27 (SS-132) was an older submarine, built in 1919 and commissioned in 1924. In the 1930s, she was stationed in Hawaii, before being overhauled in California in 1941. In June of 1942, S-27 began her first and only Aleutian Islands patrol, around Adak Island and Constantine Harbor off Amchitka Island from June 12-18. The crew found no signs of the Japanese (who had invaded nearby Kiska and Attu Islands and bombed Amchitka) in the evacuated village in Constantine Harbor, and they began to head towards Kiska.Shipwrecked off Amchitka

On the evening of June 18, in a dense fog (typical Aleutian weather), S-27 surfaced to recharge her engine batteries, and drifted towards rock breakers. Her crew raised the alarm and tried to go backwards, but with no luck. S-27 couldn’t move forwards or backwards, and her hull was ripped open, letting in water.Commanding officer Lieutenant H.L. Jukes decided to get his crew off the sinking submarine, and they used a small rubber lifeboat to ferry the crew from the sub to the beach, two or three men at a time, for the crew of 50 or so. The rest of that night, and for the next few days, men were able to get back on the submarine to take more supplies off, as well as destroy equipment and classified documents, so they wouldn’t fall into enemy hands.

George Herold, a Seaman First Class, on S-27 remembers: And I think [Chuckle] we were only at sea maybe seven or eight days – off Amchitka Island, when … our mishap started. We … its funny, we submerged all day, and you [we] come up at night to charge batteries. And you go … so it’s all enemy territory around Kiska Island. We would surface at night, and we just lay-to in the water and charge batteries. At that time, that old S-boat … it couldn’t go forward, or back – it couldn’t have any propulsion while charging the batteries. We just had to lay-to in the water. And while we were laying-to in the water, we drifted close into land. And the visibility was, was no … we couldn’t see - we had no radar at that time, or anything like that. And we drifted in toward the southeastern coast of Amchitka. And as soon as the battery charge was over, about 2:30 in the morning, we went ahead on one engine. And we almost immediately struck a reef area – a rock area. And it … holed the boat – by the hull. And we started taking on water. And we had … we, it didn’t sink right away. But, in six hours, we knew had to get off that boat. So, we had [Chuckle] … it was a funny thing - we had one rubber life raft. And we had to go back and forth to … we were off the southeastern coast of Amchitka. It was really a rocky area – a really crummy area. There [it] was … [un]inhabited, there was nothing, there was no animals, or no nothing it was just cold water and rocks it seemed like. And we finally got the crew off of there - with two or three men, back and forth, in this one little rubber life raft we had.

Constantine Harbor

S-27’s crew set up camp in Constantine Harbor, first sleeping in the open, and then using existing buildings and equipment from the evacuated village, and eating food salvaged from the submarine. After spending five nights on the uninhabited island, the crew was rescued by Lieutenant Julius A. Raven, flying a Navy PBY Catalina on June 24. He took about a dozen crewmembers, and on June 25, three more planes came to rescue everyone else. As George Herold remembers, “Yes, he … he lost his life two months later. Remember, I said he found us on June 24th. We sank on the 19th, and we lived on the island until June 24th - until he found us there. And he landed in … well you’re familiar with Amchitka - Constantine Harbor? He landed in Constantine Harbor. And there was an old dory there that was a rowboat. That was really an old worm-eaten thing - like that. So, we, one or two or of us, really - I wasn’t one of them, but we rowed out to where he had anchored his airplane in the water. And … I [Chuckle] I hope this all makes sense. And we introduced ourselves, and he took, he took about 12 or 13 of us back to Dutch Harbor from Amchitka. That, that’s a, I guess that’s a six or seven hour flight, whatever it is - like that. And the next day, two or three more airplanes come [sic] back, and then, picked the rest of us up and flew us all back to Dutch Harbor.”George Herold again: Now, a day or two before, before all this happened, we had reconnoitered Constantine Harbor on Amchitka, where they had a little Aleut village there of maybe six or seven houses – little small houses and a church. And evidently, the Japanese had dropped a stick of bombs there. And three or four of the houses were destroyed. So when we went aground on the other side of the island, we had to walk across the island carrying all our supplies – food that we got. And we stayed; we lived in these houses … and the one small church there. It was like a little … I guess it was six houses and one church is what it was. And three of the houses were destroyed by a … somebody dropped a stick of bombs. And I still don’t know whether it was the Japanese, or whether it was the Americans. I don’t know. But I know, there were six or seven bomb craters across there, and three of the homes were destroyed. So, that’s where we lived – we stayed for six days until they found us. And they found us by accident. We had sent out about six messages with the radio on the S-boat, but only one of them was received. And that one message didn’t give any position – just, that we had grounded on the southeastern, off the southeastern end of Amchitka Island.

Since the crew was able to go back and forth for a few days, from the beach to the partially sunk submarine, crew were able to retrieve not only essentials, but some personal items, as well. “Oh no, we got, you know…. [Chuckle] Personal effects - I had just bought a $29.00 set of dress blues in San Diego in October of 1941. And they cost … well, $29.00. And I was making $36.00 a month - $46.00. It went, at that time…. So, that was a big hunk of money. I made sure I got those dress blues off the boat. But everything else I lost – my dungarees, another pair of shoes, underwear, skivvies, socks, toiletries; all that - I left that. The only thing I got off the boat of mine, was my, that suit of dress blues - that [Chuckle] that cost me $29.00. … Oh, yeah, nobody was hurt. Nobody was … nobody lost their life. We got, we … we lived fairly comfortable, almost, I would say - in these houses. It seemed like … I guess it was Aleut – the Aleut people. You’d know more about this than me, now. They … they had, they left all these schoolbooks, like, for little children - with pictures of animals. But, it was all in Japanese. So, I don’t know whether they were teaching the people Japanese language there, or not. I couldn’t say that. But, you know, I’m just sorry I didn’t pick up some of these books and take them with me. But, I … at 18 years old, [Chuckle] well, one doesn’t think like that – like, I could have saved some of that that they had there.”

After the Sinking of S-27

After their rescue and return to Dutch Harbor, Navy officials set up a court martial to look into the sinking of S-27. “There was gonna be a court martial on our captain – his name was Herbert Jukes [Herbert L. Jukes]. There was gonna be a court martial set up, because he …he went aground and lost his ship. But, it was all bunk because it was so foolish. It was an old boat … was built in 1924. It had no radar, no fathometer - no anything, really. We, we had a … if we didn’t see the sun or the stars, we were lost. And that’s what we did – we had bad weather there for two or three days and we couldn’t see anything, and … the night of the 18th of June, we lay-to in the water to charge the batteries. And while we were laying-to, we drifted right in close to the beach of Amchitka not knowing that we were there – pitch dark and at 2:30 in the morning. When the charge was complete, we went ahead on one main engine, like I said before, and we immediately struck a reef. And the boat was holed, and that was the end of that. That was the … the boat was doomed after that - there was no saving it at all. … Just a matter of time, and it … it sank all the way to the bottom. But, the water was not … it [the boat] didn’t completely go under – The fore part of the boat was still up, and we could … we all got up on deck - we were OK. [Janis Kozlowski: So, you didn’t think it was the captain’s fault? George Herold: We what now? Janis Kozlowski: You didn’t think it was the captain’s fault – [for] what happened?] George Herold: Definitely not - absolutely not. No. No. There was a court martial, and … there was a lot of questions asked. And it was decided, that in no way.... In fact, he … he was given command of another submarine [USS Kingfish] – he made several patrols on the ship. Let’s see, I can’t … I did know the name. I could look it up and find out. But, anyway, then he had some success – he sank several ships on another … another submarine, after that.”Julius A. Raven, Lieutenant, junior grade, was awarded the Air Medal for “meritous achievement and extreme courage while effecting a rescue at sea.” Lt. Raven was later lots at sea during a mission on August 9, 1942. He was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for “action against enemy forces during the Aleutian Islands Campaign.”

US Navy

S-32

S-32 was a smaller, older submarine, laid down in 1918 and commissioned in 1922. In the summer of 1923, she visited the Aleutian Islands for the first time, doing cold weather exercises, before returning to warmer waters around California and the Philippines. The S-32 was decommissioned and berthed at League Island in December of 1937. On September 18, 1940, S-32 was recommissioned and had her first World War II patrol in July 1942, off the Aleutian Islands.During S-32’s tenure in the Aleutians, she patrolled from Unalaska to Attu and beyond, to the Kuril Islands and Paramushir, near Russia. She shot at a few enemy targets and one caught fire from her attack. At the end of October, 1942, S-32 returned to Dutch Harbor before going to San Diego, CA for an overhaul. Between December 1942 and February 1943, S-32 helped the West Coast Sound School, before returning to Dutch Harbor and Unalaska for her 6th war patrol.

Her 6th war patrol resulted in destroying five enemy destroyers and submarines around Attu. Poor weather and visibility prevented S-32 from making many attacks while patrolling the Kuril Islands. She left the Aleutians for the last time May 27, 1943 for San Diego, CA and provided training services for the rest of the war. Despite receiving five battle stars during World War II, after S-32 was decommissioned, she was sold for scrapping in 1946.

Naval History and Heritage Command, NH 99280

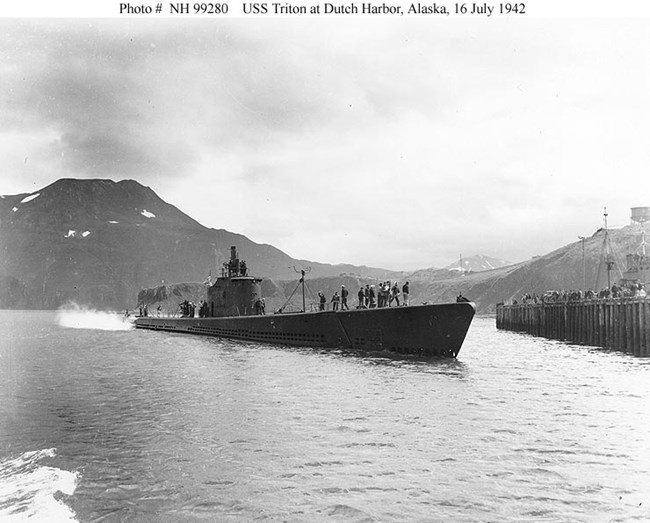

Triton III

The USS Triton III was one of twelve Tambor-class submarines. She was laid down in 1939 and commissioned in 1940. Her 4th patrol was June 25-August 24, 1942 around Agattu Island (east of Attu). During the two-month patrol, she sank the Japanese destroyer Nenohi and hit another enemy ship, but there’s no official record of that sinking. The Triton returned to Pearl Harbor September 7, 1942 and was overhauled before returning to sea.About a year after the Battle of Wake Island (December 1941), the Triton sank the Japanese cargo ship, Amakasu Maru No. 1 on December 23, 1942, which was later discovered by the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research.

In 1943, during her 6th patrol, the Triton was sunk by the Japanese off the Solomon Islands and all her crew was lost. The Triton received five battle stars. According to the Navy’s official records, the Triton officially sank or probably sank, eleven Japanese vessels.

I.R. Lloyd

Tuna II

USS Tuna II (laid down in 1939 and commissioned in 1941) began her Aleutian Islands patrol July 13, 1942, and only spotted one Japanese I-boat, before losing it in the notorious Aleutian fog and heavy weather. She also helped transport a colonel and six enlisted men from Dutch Harbor (Amaknak Island, near Unalaska) to Kuluk Bay (Adak Island) between August 25-27. The Tuna II returned to Pearl Harbor September 5, 1942, and eventually made her way to Brisbane, Australia.During World War II, the Tuna II earned seven battle stars. After the war, Tuna II was selected as a target vessel for the atomic bomb tests at Bikini Atoll, in the Marshall Islands in 1946 (Operation Crossroads). No personnel were on the submarines (or other vessels) at the time of the bomb tests, although personnel did return afterwards to clean up the vessels. The two atomic bomb tests did minimal damage to the Tuna II, and she sailed to the Mare Island Naval Shipyard where she underwent radiological and structural studies. The Tuna II was decommissioned in 1946 and towed to sea where she was intentionally sunk on September 24, 1948.

According to an unclassified report from the Bureau of Ships Group, “No damage was suffered by this vessel in Test BAKER; whether or not radio-activity would have caused personnel casualties inside the pressure hull this commanding officer cannot say. The only radio-activity found alter reboarding, was topside. … No personnel casualties would have occurred except possibly from radiological effects. Inside of ship was below radiological tolerance when opened up. Total effect on fighting efficiency. None.”

Additional Information and References

- USS Finback History (Naval History and Heritage Command)

- USS Finback Patrol Summary (Naval History and Heritage Command)

- S-27 History (Naval History and Heritage Command)

- Loss of the S-27 (Naval History and Heritage Command)

- Interview with George Herold and Harry Suomi (NPS pdf)

- The Silent Service in World War II (Chapter 6: The First and Only Patrol of S-27 (S-132) by George Herold), edited by Michael Green & Edward Monroe-Jones, 2012.

- Julius A. Raven Profile (Naval History and Heritage Command)

- S-32 History (Naval History and Heritage Command)

- S-33 (January 2023 Williwaw Newsletter)

- USS Triton III History (Naval History and Heritage Command)

- Loss of the USS Triton III (Naval History and Heritage Command)

- USS Tuna II History (Naval History and Heritage Command)

- Japanese Naval and Merchant Ship Losses (Naval History and Heritage Command)

- Submarines in the Pacific (San Francisco Maritime National Park Association)

- Operation Crossroads

- After Crossroads: The Fate of the Atomic Bomb Target Fleet (JSTOR)

- Unclassified Technical Inspection Report on Tuna (pdf)

- Operations Crossroads (Naval History and Heritage Command)

- Operation Crossroads (Atomic Heritage Foundation)