Last updated: April 7, 2025

Article

Adaptive Reuse of the American Zinc Building and Other Works

Gyo Obata, HOK

American Zinc Building

Okay. It's interesting that I'm in a building that I designed many, many years ago, and it's what's called American Zinc Building.

Actually, the Park Service was responsible for helping preserve it.

At one time, this building and the older building that the hotel is in, was slated to be torn down, but Esley Hamilton and others in the city fought to preserve it, and so it was saved.

Ray Wittcoff was the owner of the Fur Exchange Building, the older building, and he got this smaller lot on the corner, and he asked me to design a headquarters for American Zinc Company.

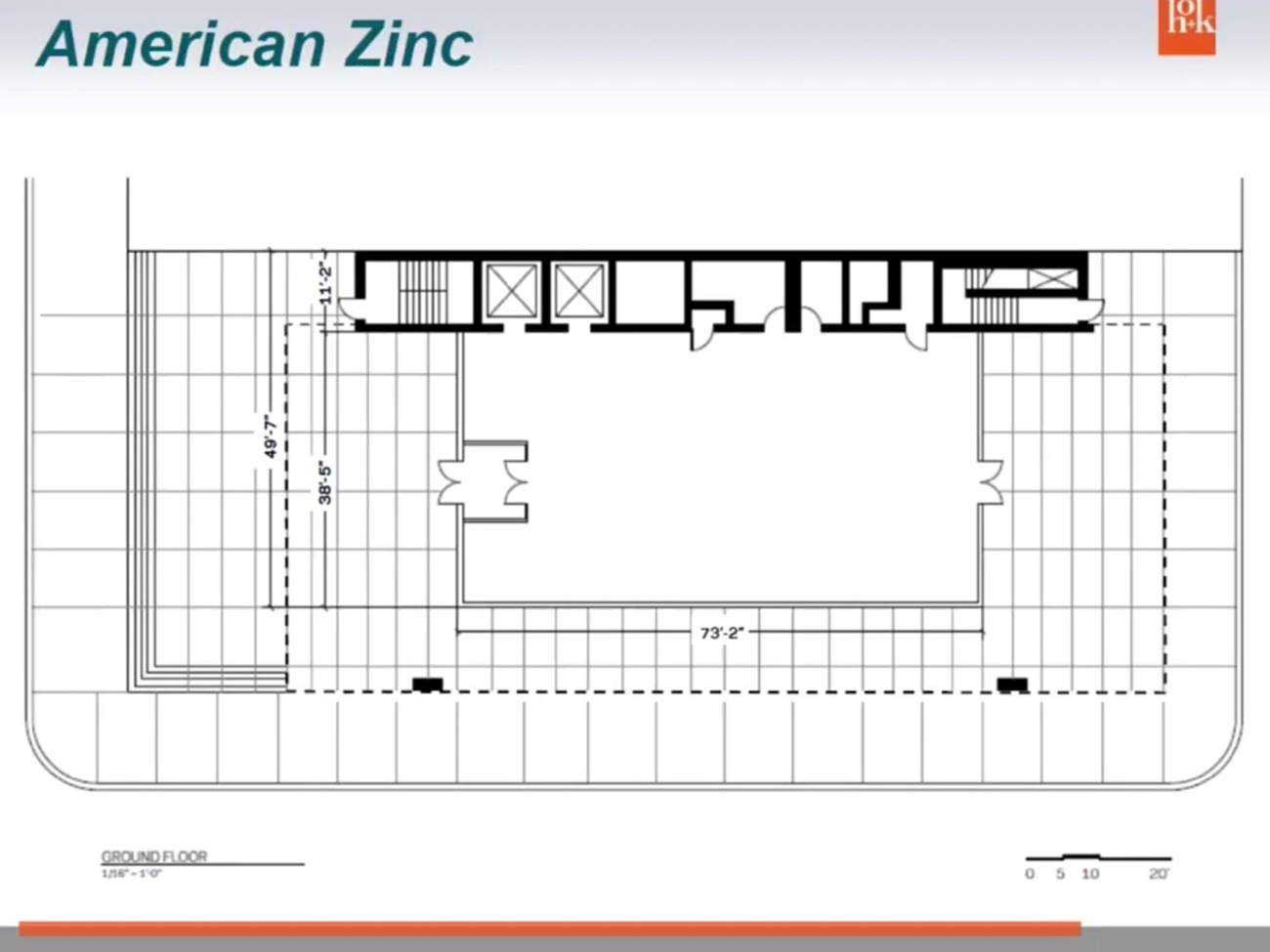

The site is about 60 foot wide, by 170 foot long, and so what I did was to put all of the fixed element, the stairways, the elevators, on the north side, and I could have a clear span of 50 feet within the site.

This is the main ground level. I think it's wonderful to preserve a building like this.

Remodeling

Also, I think that the people that then remodeled it ought to have some sensitivity, but I don't think they really did. You could see these additions that they put on on the end and so forth.

Anyway, it was really clear span of 60 feet by about 110 feet, and all of the fixed elements are on one side.

Gyo Obata, HOK

The office space was wide open.

I think these were all sort of this traditional stuff was added on once the hotel took it over, but it used to be just a beautiful open space.

I wanted to use zinc as the exterior material because it was their headquarters, but zinc was not available as a building material at that time, and so I went to stainless steel.

You could see that the façade on one side is vierendeel truss. The whole block was a vierendeel truss, so you have that three span coming over.

That shows again the vierendeel truss and then the open span, and then the Fur Exchange Building to the back.

Gyo Obata, HOK

This is a front that shows the clear span of 50 feet, and then the coming under protected to the main entrance.

St. Louis' Lambert International Airport

The next few slides I'm going to talk about in the 60's there were some very interesting concrete buildings done.

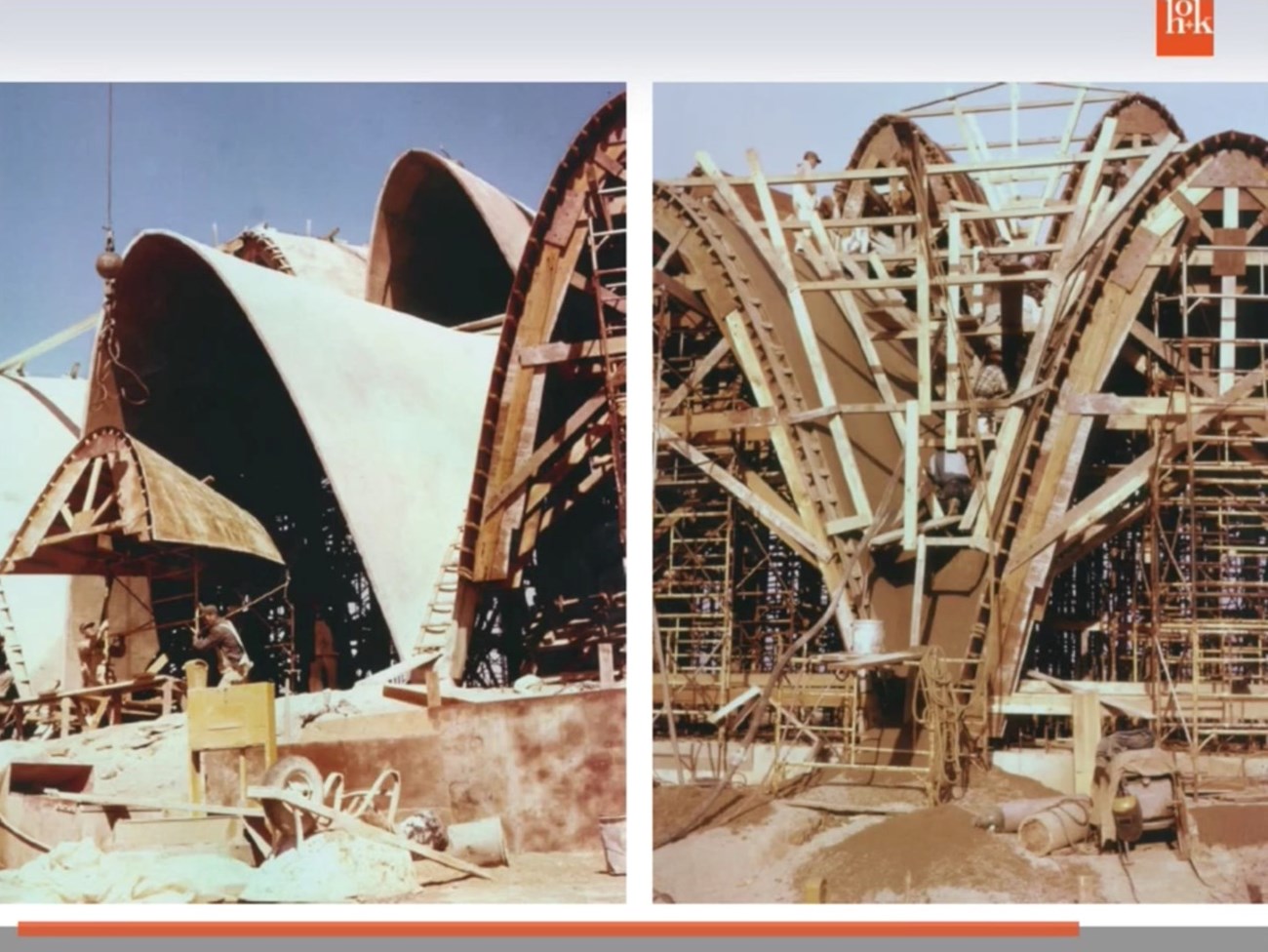

Concrete was … We were able to use concrete because it was … When you build concrete structure, you have to build another structure, wooden structure, to pour the shell over it.

The labor cost was still such that you could afford concrete structures, but now it's really much more difficult to do.

This is an airport that Yamasaki and I did for St. Louis Lambert Airport. At the beginning there were three arches, 120 by 120 foot wide. This is an older drawing, but each of those spaces were 120 by 120.

Gyo Obata, HOK

Then this shows another bay was added.

This is a fairly recent picture, but the tornado, several years ago, took away a lot of the copper roof.

This is all new copper roof on the building.

You notice those beams going diagonally across the area. Yama and I really didn't wasn't those beams, but the structural engineers said that we needed those for structure.

Later on, he admitted that he could have eliminated them by making the corner for the arches come together, thicking it.

Which I did on one of the building I'll show you next. A clear span. Yama's idea was to try to make this building like Grand Central Station, a gateway to St. Louis.

Gyo Obata, HOK

St. Louis Planetarium

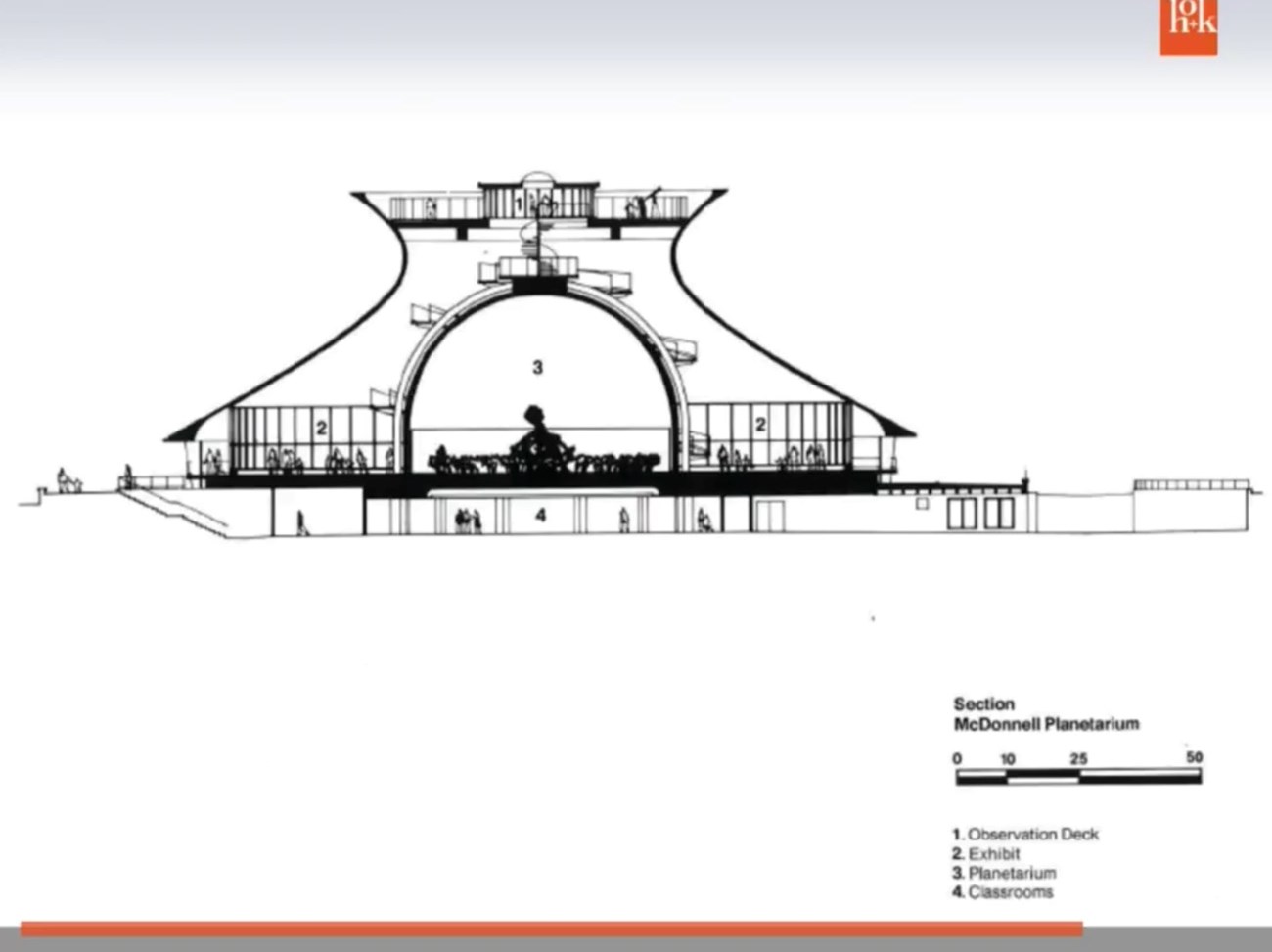

This is a planetarium, another concrete structure that was built during that period.

It's a thin shelled concrete.

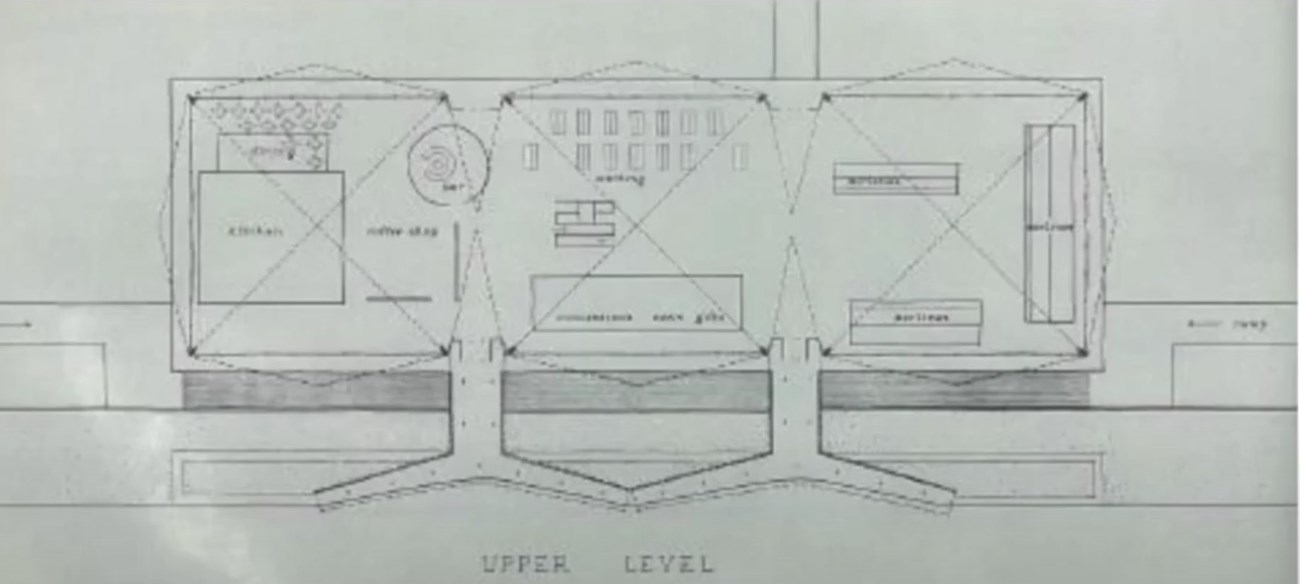

The reason for this form was there was a planetarium inside, and then there was a stairway there wrapped around that planetarium.

You could go up to the roof, and from the roof, after the show, actually see the stars.

They've remodeled it now so that the whole interior is quite different than the way it was designed.

Gyo Obata, HOK

This is the Priory Chapel. I think you're going to go visit, but this was built for benedictine monks who came from England to setup a boy's secondary school in St. Louis.

They wanted a round church because they felt that it would bring all the boys much closer to the center and they could pay more attention to the …

That's the section through the first arches, the main name, the second arches of the sanctuary, and then the bell tower is at the top.

The bell tower is the Benedictine building element that they used in many of their buildings.

When you build a concrete thin-shell structure, you have to build the whole structure out of wood.

There are four sections that they moved around.

It was interesting when we put out the … made the drawings and put it out to bid, almost no contractor wanted to build it because it was too difficult they said.

Gyo Obata, HOK

In fact, McCarthy brothers, who got the bid, elder brother who was the head of the company threw the working drawings in the waste basket.

Then his brother, Paddy, picked it up and really researched it, and figured out how he could build it.

Paddy was responsible for getting it built.

I mean architects can do innovative designs, but you also need contractors who are willing to take the chance to build it.

That shows the thin concrete.

Thank you.

National Park Service

Biography of Gyo Obata

Gyo Obata is an American architect. In 1955, he co-founded global architectural firm HOK (formerly Hellmuth, Obata + Kassabaum). He lives in St. Louis, Missouri and still works in HOK's St. Louis office.

He has designed several notable buildings, including the McDonnell Planetarium at the Saint Louis Science Center, the Independence Temple of the Community of Christ church and the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C.