Last updated: January 23, 2025

Article

“Achieving the Liberties of America” – the Story of Prince Jenckes

What's in a name?

In the late 1770s, hundreds of African people living in Rhode Island shared a name with their captor. One of these men was called Prince Jenckes.

This is his story of service, on and off the battlefield.

***

Prince Jenckes became a solider in late February 1777.

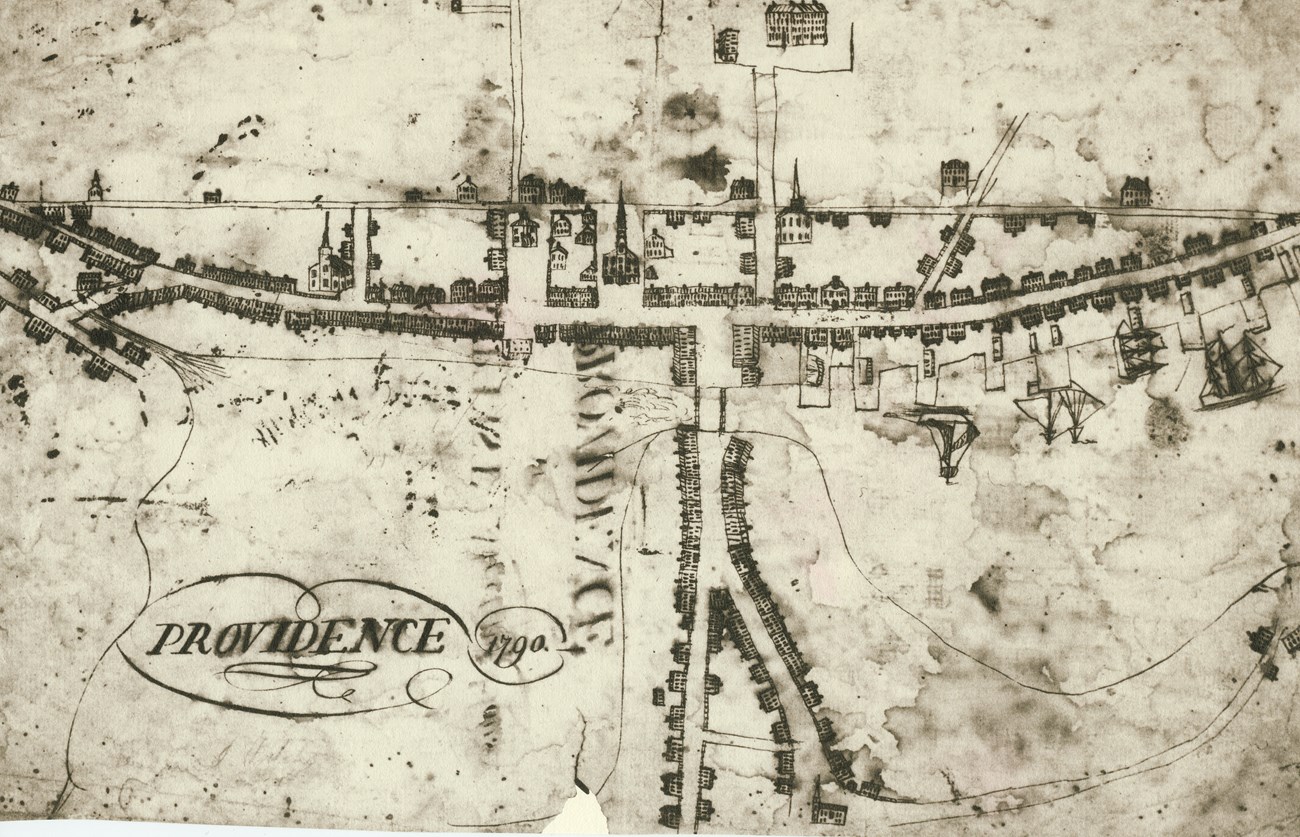

Less than a year after the Declaration of Independence, Prince enlisted with the Continental Army. Prince had black hair and stood five feet six inches. He was born somewhere in Guinea, and after enduring the Middle Passage, Prince became a resident of Providence, Rhode Island. For his occupation, Prince was listed as a laborer, but of course, the fruits of that labor were never his own. On official records, Prince’s identity was bound up in his servitude. He was listed as a “slave of John Jenckes,” a Providence man and prominent resident of the colony.

During the American Revolution, Prince was one of thousands of people of African descendant who waged a war for independence alongside those who sought to keep them in bondage. Prince’s service included time as a drummer and later as a private. The first major trial that Prince survived was his captivity and journey to the Americas. The second was the War for Independence, during which he traveled for almost six years. Though military records are sparse, these documents provide important insights into a life that otherwise might be nearly impossible to research. Other historic records, including a newspaper article featuring a letter written by Prince, fill in additional details about his life in and away from Providence.

To understand Prince’s time as a solider, it is important to first uncover why he might have been forced to serve in the first place. Historian Clare Tyler has done extensive research to uncover Jenckes’s life story. She argues that John Jenckes, “a member of the RI legislature” had to be aware, and “surely saw” news of “Congress’s offer for enlistment” in 1777. Men who responded to the Congress’s call would receive “a 20-dollar bounty, a new suit and 100 acres of land after the war was over.”1 Unwilling to fight himself, John had enslaved men fight for him and the patriots’ cause: Prince and another man named Primus.

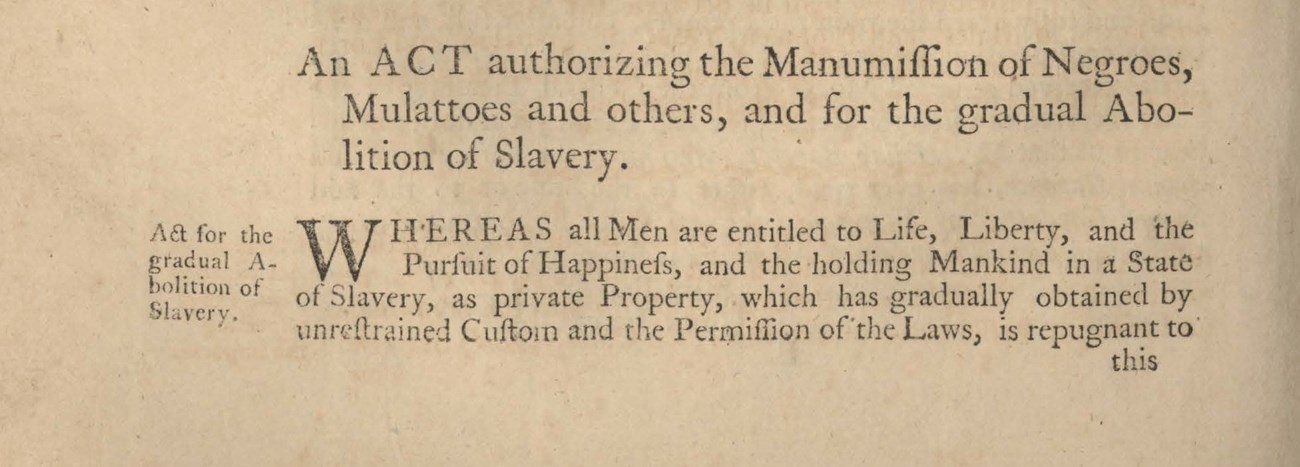

Prince Jenckes’s time as a soldier was indelibly shaped by a law that would further incentivize the enlistment of Black men. A year after Jencks’s enlistment, the Rhode Island General Assembly passed an Act that would form the 1st Rhode Island Regiment, which would later be known as the “Black Regiment.” Of course, other persons of African descent were already serving in Rhode Island and elsewhere, but this ensured that "every able-bodied negro, mulatto, or Indian man slave" could enlist for the duration of the war. After “passing muster” these new soldiers would “be immediately discharged from the Service of his Master or Mistress [.]” A free man “would serve as though he had never been encumbered with any Kind of Servitude or Slavery.”

In a move that would foreshadow many other decisions to placate slaveowners, legislators accounted for the fact that one man’s freedom was another person’s economic loss. The Act also reiterated that “Slaves have been, by the Laws, deemed the Property of their Owners”—which meant that manumission came with a price. The legislators agreed that “Compensation ought to be made to the Owners for the Loss of their Service: It is further Voted and Resolved, That there be allowed, and paid by this State, to the Owner, for every such Slave so enlisting, a Sum according to his Worth.” Five years after Prince and Primus were enlisted, John received “thirty six pounds six shillings and four pence one farthing silver money” from “the general treasury” as payment for “his negro man Prince who enlisted into the Continental service.”2 A payment for Primus’s time in service was also sent to John.

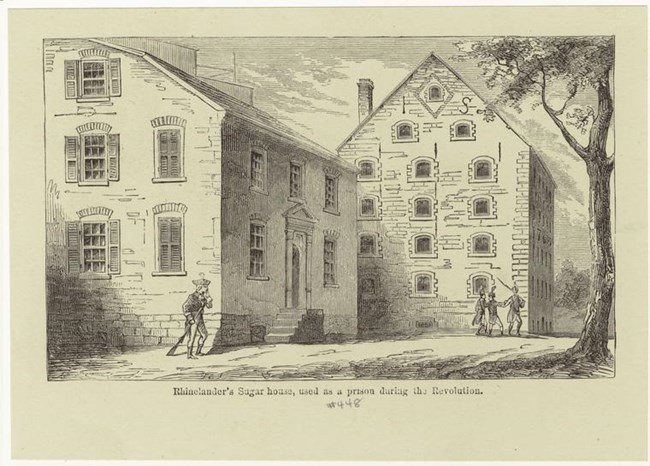

Such provisions came at a time when few soldiers, Black or white, saw proper wages, if any at all, for their service. By the time John was petitioning for these small payments, Prince’s military career had taken him far from Rhode Island. After his start with the Continental Army, Prince was transferred to be a drummer with the Rhode Island First Regiment, along with Primus. Much of what can be gleaned about this time in Prince’s life comes from the written records of fellow soldier Jeremiah Greenman, who became an officer and documented his time at war. After more local battles, Prince fought at Pines Bridge, New York in May 1781. He was later captured by British forces and survived confinement as a prisoner in a sugar house (a place for making syrup). A few months later in September, his unit was released. In 1782, Prince spent part of the year traveling in Pennsylvania, returning to the site of the Battle of Red Bank, before going back to New York.

After a short period of reprieve, Prince was part of an expedition to capture Fort Oswego (Fort Ontario) in February 1783. He suffered greatly in a bitter cold winter, ultimately losing part of a number of his toes. How precarious this wartime freedom was for Prince, even after leaving the Jenckes homestead on Benefit Street.

Prince was discharged from the military on June 28, 1783, more than six years after John had enlisted him. Prince should have been given a pension, but Tyler’s extensive research shows no evidence that he was supported by one. By now, Prince’s captor had already received financial reward, but there was no support for a freedman such as Prince to start his life over. Instead, Tyler’s research shows that Prince was given support in other, meager ways from the city, and ended up in a workhouse. Their work also demonstrates that Prince was denied non-monetary recognition. Although he was “one of the longer serving in his regiment…he never moved past drummer. Indeed, the records indicate a reduction in rank without giving a reason for it.”3

Mere months before Prince’s service ended, Rhode Island passed the Gradual Emancipation Act, declaring that no one “born within the limits of the state, on or after the first day of March, AD 1784, shall be deemed or considered as servants for life, or slaves [.]” This was not immediate emancipation. Some people would be kept in bondage for decades, and children born to enslaved people would work as unpaid apprentices until age 18 or 21. This law also had no provisions about civil rights and would not create any imminent changes in the daily lives of freedmen like Prince.

There are no clear records as to how Prince spent his first years after freedom, but they were undoubtedly difficult due to his financial situation and lingering health problems. Once again, information about Prince’s life primarily enters the historical record through the financial transactions of others. Money seems to have circulated between men of power around Prince, rarely finding its way into his pockets. In late 1787, a Providence doctor was paid by the overseers of the poor for “attending Prince Jenckes a Black invalid Soldier who has had his Legg Amputated…”4 Finding equitable, safe work as a Black freeman before the war would have been difficult. Securing steady employment as a man with significant injuries after it seems to have been nearly impossible. Whereas some veterans of the war would come home to farms in need of repair, Prince ended his time in the war free, but without social connection or opportunity.

There are no plaques or monuments for Prince and Primus. In Prince’s case, however, there is a final letter that speaks to his condition of life at the end of the 18th century. During “the winter of 1799,” Prince Jenckes either wrote or dictated the following plea for help to a “Mrs. F----.” He explained his circumstances: “I am poor, Madam---- so miserably poor, that all my possessions are about two thirds of a human body, containing, however, a grateful heart. There is not left me even to choose between working and begging.” Prince was suffering from his debility, and by this point, entirely destitute. In his life as a free person in the Early Republic, Prince found himself unable even to beg. He concluded: “To him who has nothing any thing will be acceptable, and ever so little will be valuable…” As many other veterans would do, Prince also invoked his service in the war, and his proximity to the man now finishing his time as President: “I assisted General Washington, Madam, in achieving the liberties of America.”

Freedom was not just tenuous, at best, for a man like Prince. George Washington himself owned hundreds of people throughout his lifetime, and enslaved labor sustained the first White House. During the war, Washington’s aide William Whipple also enslaved a man called Prince, who in turn fought for “the liberties of America.” Of the two million people in bondage in the United States in 1800, a good number would have shared a name with Prince Jenckes from Providence, as this was among the more common names given to enslaved men. Classical and aristocratic names were not given to enslaved people like Prince out of respect, but to demean their humanity. In a port city where many families tied their wealth to the trade of human beings, the name Prince Jenckes was both distinctive and revealing—it would say something about who owned him, and where he was forced to live. Patriots who no longer wanted to be ruled by aristocrats still found ways to assert their power over Princes.

In his final letter, Prince Jenckes did not seek acclaim, financial gain, or any great earthly reward. He wanted “gratification” and comfort in the form of a warm meal and protection from the elements. Throughout his life, Prince was a man who made music, whose drum alerted his fellow soldiers and set the rhythm for their days. He was a laborer whose works, if they have survived, would now be attributed to “a craftsman unknown.” At various stages of life, Prince was a slave, a soldier, and a supplicant. He was also a citizen in a new country asking for meager support from a public who owed him a great debt. To date, only his captors have been repaid.

Notes:

1) Clare Tyler, “ Prince Jenckes a Black invalid Soldier”: A Unique Case of Disability, Race and Poverty in the Early United States” (undergraduate thesis, University of Rhode Island, 2022), 20.

2) Records of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, in New England: 1780-1783 (1864): August 1782.

3) Tyler, “Prince Jenckes,” 72.

4) Tyler, 56.