Last updated: January 27, 2021

Article

Frank Distefano is Acadia's "Moth Man"

Photo courtesy Catherine Schmitt

by Catherine Schmitt

Science Communication Specialist

Schoodic Institute at Acadia National Park

“Mothing is night employment. Skunks and toads entomologize at night. Early in the morning, at sunrise, when the dew is still on the leaves, insects are sluggish and easily taken with the hand; so at dusk when many species are found flying; and in the night, when many species fly that hide themselves by day, and many caterpillars leave their retreats to come out and feed, and the lantern can be used with success to draw them out, the collector will be rewarded with many rarities.”

– Alpheus S. Packard Jr., 1862. “How to observe and collect insects,” Entomological Report, pp. 143-219 in Second Annual Report Upon the Natural History and Geology of the State of Maine, Board of Agriculture

Since 2016, Frank Distefano aka "Moth Man" has documented moths with photography, contributing the images to a global database of biodiversity at DiscoverLife.org. Last year, his fourth consecutive year conducting moth studies on Mount Desert Island, he set up his "collector," a white sheet with high-powered lighting, at the Wonderland parking area as dusk descended on Mount Desert Island. His wife, Melody, settled into a folding camp chair with a book. Frank watched the sheet and waited for the moths to arrive.

A research chemist by day, Frank DiStefano began photographing moths nine years ago, after similar enchantments with butterflies, dragonflies, and orchids. He found moths to have several advantages to the collector. Most moths are easily attracted with light or bait (stale beer, ripe bananas, brown sugar). They are easy to photograph close-up, as they land still and flat-winged (butterflies move around more and tend to fold their wings closed). And there are more than a thousand different kinds of moths, so he never runs out or gets bored. Moths are very ancient, about 190 million years old, older than butterflies, and so have had a lot of time to evolve into different shapes, sizes, colors, and behaviors.

Over the course of two hours, more than 50 species of moths visited the light station. If a new or particularly interesting moth stopped by, Melody came over to see. Many people driving past stopped to check out the moths: Marbled Green, Putnam’s Looper, Harris’ Three Spot, Sphinx (“big and clumsy”), Virginia Ctenucha. Frank knew many of them, but many he did not, and he frequently reached for a field guide, but just as often was content to simply look and take pictures.

Frank DiStefano would find good company in the naturalists of the nineteenth century. Back then, there was no pressure to pick a single subject for a lifetime of work, although people did tend to have favorites.

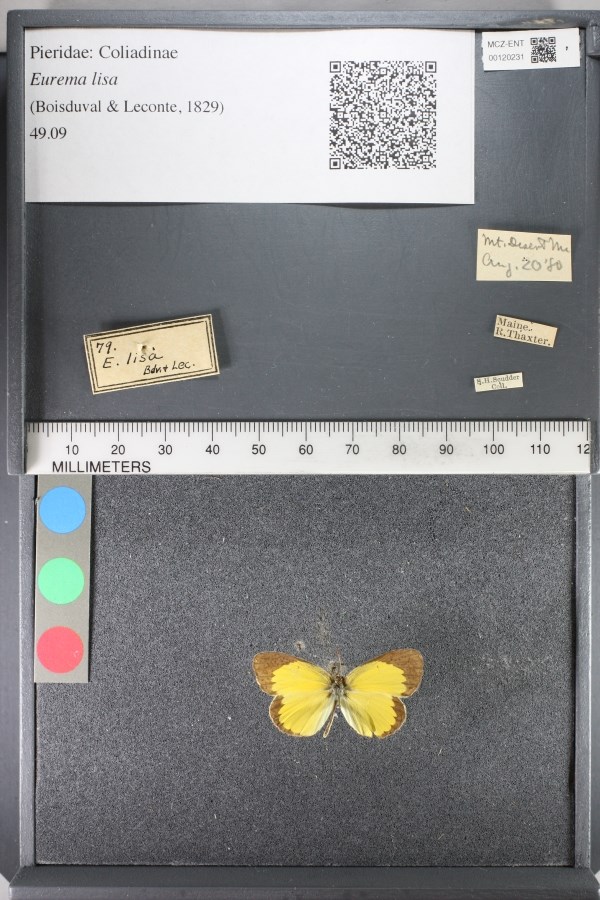

Moths and butterflies were definitely a favorite subject of young Roland Thaxter, who collected the first preserved specimen from Acadia while camping on Mount Desert Island as a member of the Champlain Society in August 1880. The preserved specimen was a Little Sulphur (Eurema lisa), which Thaxter claimed had “never before been seen so far North.” He also collected geometrids and Glover’s Silk Moth.

Thaxter exchanged notes with Samuel Scudder, president of the Boston Society of Natural History, and shared his Little Sulphur record, which Scudder presented to the society in 1882. Scudder also made collecting trips to Mount Desert Island, and included the records in his three-volume Butterflies of the Eastern United States and Canada with Special Reference to New England in 1889.

Maria and Charles Fernald of Orono, Maine, were some of the most knowledgeable entomologists of the era. In 1884, Charles published the Preliminary List of the Lepidoptera of Maine and Maria Fernald published three lists of the larger moths in the Canadian Entomologist.

“The butterfly science of the 1880s was a fascinating mixture of scientific confidence and human longing,” wrote William Leach in Butterfly People: An American Encounter with the Beauty of the World. “Scudder [and other naturalists] all saw aesthetics as bettering civilization, as beneficial to science, as something meant to satisfy or meet human needs, not necessarily only as a consequence of natural selection. An ally of science, not its competitor or usurper, beauty drew Americans to Lepidoptera, setting them on paths to lifetime fulfillment. Their natural history formed a high point to a remarkable moment when, through the lens of the butterfly, many Americans became aware of all the shapes, colors, patterns, and surfaces around them that nature was capable of creating, the existing species and genera, real or mimicked, solitary or communal, the variations, dimorphisms and polymorphisms, the emergent new organisms struggling for identity and stability, in a kaleidoscope of ever-changing relationships revealed to Americans, in part, by the Darwinian revolution and, in part, by their own eyes.”

Twentieth-century moth men and women who worked in Acadia include Auburn Brower, Ruby Dow, Charles Gay, Charles Johnson, Charles Minot, A.H. Moeck, William Procter, and R.E. Stanford.

Back then, “collecting” meant capturing, killing, and preserving butterflies and moths. Today, high-resolution photography offers a way to document biodiversity without harm.

To find and photograph different moths, the DiStefanos travel to other places around the country besides Acadia, including Everglades National Park in Florida and Rocky Mountain National Park in Colorado, and parks in Costa Rica. After more than one hundred thousand photographs, DiStefano claims to be no expert. His humility—and his enthusiasm—were on display as he stood before the moths decorating the white sheet in the dark summer Acadia night.

"In addition to being pollinators and a food source for species such as bats, birds and amphibians, the decline in moth populations over the past few decades is an indicator of a deterioration in our environment as a whole."