Last updated: December 9, 2022

Article

Shenandoah: An Abused Landscape?

by Reed Engle, Cultural Resources Specialist

Preface

Shenandoah National Park was authorized by Congress after a thorough and wide-ranging survey of various proposed locations by the Southern Appalachian National Park Committee, a group composed of park planners, arborists, and scientists. The group recommended the northern Blue Ridge Mountains, believing the area met National Park Service standards for new parks. Early scientific evaluation of the park's forest communities conducted by the Civilian Conservation Corps echoed early publications that described the woodland wonders of Shenandoah. It was not until the 1960s that a new environmental history of the park began to be developed, one that characterized the pre-park natural history as one of wanton agricultural abuse, severe erosion, and the clear-cutting of the forest. Although many sections of the East, and many more agricultural areas of the South, did suffer such abuse, historical research in the past decade indicates that the exploitation of the Blue Ridge was primarily the responsibility of absentee landowners, and the park area was not a vast wasteland left for natural forces to reclaim.

Ohio Agricultural Experiment Station, 1916

The Context: Land Use in the East

Nineteenth century America was built on the extraction and use of its natural resources. As railroads spanned the continent, they demanded an endless supply of timber for ties and carried boxcar after boxcar of rough-sawn planks to build the new residences and western towns developed by the railroad companies. In a time before synthetics, leather was used for everything from footwear to the drive belts that transferred power from wood-powered steam engines. Leather was processed with tannic acid derived from bark, typically from chestnut oak (Quercus montanus), hemlock (Tsuga canadensis), white oak (Quercus alba), or chestnut (Castanea dentata). Borst's Tannery in Luray, a major supplier of Confederate leather goods, was burnt by the Union Army in 1863. It was followed by the Virginia Oak Tannery that continued to demand an endless supply of bark from adjacent woodlands.

Seen in the above photograph from Ohio, tanbark was stripped from trees in the early spring with a tool called a spud. The bark was left to dry until it was taken to the tannery for leather production. As shown in Ohio, and in the Blue Ridge Mountains, chestnut oak (Quercus prinus) was the favored tree for bark. 1

The Shenandoah Valley was a national center of iron production throughout the 19th century because it had, or was close to, abundant supplies of iron ore, limestone, and charcoal, the necessary ingredients for iron production. Iron provided the rails for the trains and the boilers for the steam engines, but required massive quantities of charcoal. Typically 1-6 acres of trees were required to produce the charcoal needed for a single day's output of an iron furnace, upwards of 1,700-1,800 acres per year/ per furnace. 2Within the proposed Shenandoah National Park one large tract, owned by John A. Alexander, typified the industrial and commercial exploitation of land in the eastern United States before and after the Civil War. Most of the property (19,554 acres) was located in Rockingham County, but small parts extended into Augusta, Greene, and Albemarle Counties. The State Commission on Conservation and Development survey of the property in 1927 stated:

The entire tract (21,103 acres) was appraised at $35,605.50, an average value per acre of $1.69, as part of the Virginia condemnation for park lands.4 In contrast, the most productive land in the future park area was appraised at $50.00/acre.Although the Alexander tract is possibly the extreme, both in the East and certainly within Shenandoah National Park, by the 1940s only between 0.1%-1.0% of the land east of the Mississippi River remained old-growth forest.5 The great virgin forests of the East were a long-forgotten memory by the time Shenandoah National Park was established. They had been sacrificed for national expansion.This tract was worked for iron ore at one time, but has not been operated for a great many years . . . . The more accessible parts of this tract werecut over many years ago, 1865 to 1879, to provide charcoal for an ironfurnace located on Madison Run. On this portion of the tract practically no timber was left. About 1900 the chestnut oak timber was cut for bark. Since the bulk of the stand was comprised of chestnut oak, the bark operation removed the greater part of the remaining timber. Small portable mills have operated periodically over the tract for many years removing any timber which could be reached without too great difficulty . . . . Repeated incendiary fireshave run over the tract destroying the reproduction, and injuring the immature and the old timber remaining. In many places, even the soil itself has been burned with the result that extensive portions have been rendered non-productive, and almost worthless.3

The Condition of the Land within Shenandoah National Park

Beginning in 1934 the ECW (CCC) program hired an Assistant Forester, R. B. Moore, to assess the condition of the proposed park area. Over the next several years, using the labor of CCC enrollees, Moore mapped the forest or vegetative cover on 172,828 acres of the proposed park. Dividing the land into watersheds, Moore defined 16 forest cover 6 types and five age classes.7 Known forest fires were also mapped. The data were published on May 29, 1937 as "Forest Type Map Write-Up by Watersheds, Shenandoah National Park."

The broad status of the park lands was summarized in the "Acreages of Forest Types and Burns" (below). Moore showed that the mountains were not "stripped of cover," but in fact only 14.52% of the park acreage was open, either as cultivated or pasture land. Also of interest is that forest fires since 1930 had burned between 61.9% - 85.8% of the pine communities (which represented 17.71% of the forest cover) and 25.7% of the total park acreage.

| Cover Type | Total Acreage (% of Park Total) |

Acreage Burned 1930-1937 |

Percent of Type 1930-1937 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cove Hardwood | 8,333 (5.0%) | 348 | 4.1 |

| White Pine/Hardwood | 828 (0.5%) | 37 | 4.4 |

| Oak/Hickory | 4,020 (2.3%) | 817 | 20.3 |

| Mixed Oak | 87,342 (50.5%) | 15,689 | 17.9 |

| Chestnut Oak | 20,457 (11.8%) | 8,575 | 41.2 |

| Yellow Pine/Hardwoods | 17,439 (10.1%) | 11,153 | 63.3 |

| Yellow Pine/Bear Oak | 7,841 (4.5%) | 6.730 | 85.8 |

| White Oak | 138 (0.08%) | None | 0.0 |

| Mixed Oak/Fraser Fir | 64 (0.04%) | None | 0.0 |

| Black Birch | 83 (0.04%) | None | 0.0 |

| White Pine | 83 (0.04%) | None | 0.0 |

| Virginia Pine | 844 (0.49%) | 523 | 61.9 |

| Open | 25,089 (14.5%) | 294 | 1.1 |

| Barren | 267 (0.15%) | 239 | 89.0 |

| TOTAL | 172,828 | 44,425 | 25.7 |

In the detailed descriptions of the watersheds, Moore discussed the existing vegetative associations, soil types and conditions, reproduction of species, fire hazard potential, insect and fungal pests, and past history. Although he recognized that much of the park had been logged in the past, he identified eleven watersheds, or parts of watersheds, that retained significant forest communities with no evidence of previous logging activity: Hogwallow Flats, Hogback (south side), Beahms Gap (south and east sides), Pass Run to Shaver Hollow (upper slopes), the Robinson River watershed, Staunton River8, Big Run, Loft Mountain (east side), Hangman Run, Devils Ditch and the Upper Conway River, and the lower slopes of Cedar Mountain. Although these areas indicated no evidence of former logging, many did show the effects of the wildfires that swept across the mountain in 1930, 1931, and 1932, possibly aggravated by the worst drought in Virginia history.

In his 179 page report, Moore listed only four instances of significant erosion: the northwest side of Neighbor Mountain/Jeremiah Run, the South Fork of the Thornton River, Pond Branch, and the North Branch, Moormans River. At the Neighbor Mountain/Jeremiah Run and Pond Branch locations, the forester stated that the "soils were burned to such an extent . . . . that little humus is left . . . . [and] the soil on these slopes is also thin and subject to erosion" and that "the soil on the higher ridges is practically gone showing evidence of past fire and erosion." In neither case was there evidence of logging, farming, or pasturing in the eroding areas. On the South Fork, Thornton River Moore noted that there was "some evidence of erosion on the open fields [but that] . . . . this is being checked by the vegetation which is restocking the area." Only on the North Branch, Moormans River, did Moore state that the "large open pastured area has eroded badly . . . . and gullies three to four feet across have been cutinto the mineral soil." It is photographs of this single area of the park that have come to characterize the "mismanagement of the land" and "poor farming practices" of the mountain people.9

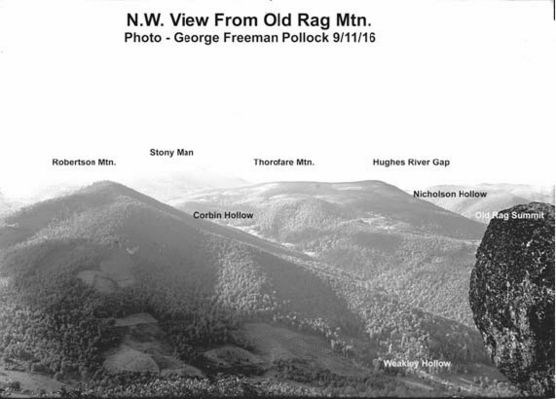

George F. Pollock, 1916

Slightly fewer than 1,100 tracts of land were purchased to create Shenandoah National Park. Approximately 465 families lived within the park area, but only 207 of those families owned the land they lived on—in other words only 19.2% of the condemned tracts were owned by the "mountain people", acreage representing slightly less than 10% of the park area.10 Only 348 of the 465 families cultivated land, and the average family cultivated but 5.27 acres, a total farmed area of 2,450 acres (1.42% of the total land within the park).11 The 22,369 remaining acres of "open land" inventoried by Moore represented pasture, orchard, and open space associated with resorts (Black Rock, Panorama, Skyland, and Swift Run). The overwhelming part of the pasture was deeded to absentee landowners who grazed their stock on the mountain slopes in the warmer months. A brief review of the Shenandoah National Park land records searching only for the obvious corporate or well-known Shenandoah Valley and Madison County landowners reveals that over 63,000 acres (37%) of the park was owned by only fourteen families and/or companies.12 Even if the Blue Ridge Mountains had been the devastated area the developing myth of the 1960s suggested, and which Moore's work contradicted, it is in hindsight hard to see how the mountain residents could be held responsible for the actions of the absentee landowners and corporate interests that owned 90% of the future park.

Recent research, in fact, suggests that the small resident mountain farmers were probably more sensitive to the land than were the non-resident landowners:

pockets of self-sufficient farms remained in places like the northern Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia. These farmers, responsive to the constraints of the mountain landscape that surrounded them, tended to rely on less invasive, century-old technologies to work their fields. Although contemporaries widely disparaged this way of life, the records of these communities reflect a long history of viability and suggest that the ecological basis of upcountry agriculture was strong.13

A Changing Interpretation of Natural History

When the Southern Appalachian National Park Committee reviewed the questionnaires submitted by localities and individuals interested in obtaining the proposed national park for their area, the Blue Ridge Mountains proposal by Pollock, Allen, and Judd gushed with description of the untrammeled landscape. Because of the questionnaire, the Committee visited the area on several trips. The members were not novices to landscape, vegetation, or parks—they were selected because most had professional expertise. Although they recognized that the Great Smoky Mountains were more rugged and remote, they believed that the Blue Ridge Mountains met the criteria established for National Park status. Nowhere in their report to Congress is there an indication that the land was gutted with erosion gullies or the scars of significant extraction activities.

In 1937 Darwin Lambert, clearly aware of Moore’s CCC forest study, wrote:

Seven-eighths of the Shenandoah National Park is covered by a green blanket of forest. This forest is composed of approximately eighty species of trees, at least that many more shrubs and vines, and almost countless kinds of smaller plants . . . . Throughout the entire area, in nearly all kinds of environments, the oaks are the most common. These oaks are of about ten different species. Chestnut oak is probably the most numerous, but there are many splendid white and red oak trees.14

Yet, four decades later the park's Statement for Management formalized a new view of the natural history of the park by noting that

before the mountains were stripped of cover, they were blanketed with a climax forest of mixed hardwoods with pockets of hemlock, balsam, and spruce . . . .Since the establishment of the Park, evidence of the settlement period has gradually faded from the scene, and most of the old homesites have become part of the deciduous forest15

Soon this viewpoint would become standardized and accepted park history by researchers:

Early in the nation's history, the mountains which now form the park were explored and hosted hunting and resource extraction activities; later, they began to serve as a refuge for the poor and landless, who became mountain people. Throughout this period, a body of folklore, legend, and archaeological materials accumulated while the land suffered increased use and degradation. Overgrazed and nearly lumbered out, the region was further affected economically in the early 1930's by the chestnut blight, which destroyed its last viable cash resource. In recognition of the plight of the area's residents and the need for lands to be preserved in their natural state near one of the nation's largest population centers, Shenandoah National Park was authorized in 1926 . . . .16

It was accepted that "over a century of heavy abuse had decimated the forests and wildlife and gullied the soils."17 The problem with this view of pre-park Shenandoah, however, is that it neither placed the Blue Ridge Mountains within the context of the natural history of the Nation east of the Mississippi, nor fairly and factually represented the condition of the land within the park. The publication of Pollock’s highly self-serving and inaccurate Skyland, and the republication of the now-discredited Hollow Folk in the late 1960s, codified the distorted lives of the mountain residents that National Park Service staff came to accept as factual. Few publications noted the extent and impact of the absentee landowners on the land within the future park, and fewer still discussed the massive erosion and impacts on natural resources caused by the construction of the Skyline Drive.18

The Blue Ridge Mountains were not virgin old-growth forest at the time of park establishment: but there were many areas that had not been logged or burned for many decades and some areas that approached old-growth status. Although a few areas demonstrated agriculturally caused erosion, far more erosion would come as a result of the construction of the Skyline Drive. Most recent research suggests that ShenandoahNational Park was established after a careful selection process because its landscape had not been plundered as the literature of the 1960s suggested. Nature was able to so quickly “reclaim” the land because the land had not been truly lost.

Endnotes

- Used by permission of the Ohio Agricultural Experiment Station, Department of Forestry, Digital Image Collection, photograph created June 1916.

- See Eliza Furnace Historic Site and Hopewell Furnace National Historic Site

- ShenandoahNational Park Archives, Resource Management Records, Land Records, RockinghamCounty, John. A. Alexander file.

- Alexander never received any profit for the land. He was in jail on a six-year sentence for fraud and embezzlement, having never paid the original owners for most of the land he "purchased" from them.

- Chestnut oak, red oak, red oak/"blue ridge fir", scarlet oak, pitch pine, white pine, bear oak, black locust, Virginia pine, cove hardwood, hemlock, grey birch, open land (restocking), open land (cultivated), open grassland, and barren (rock outcrops).

- All age, mixed age, 1-20 years, 21-40 years, and 41-60 years.

- Although Moore stated that there was no evidence of former logging in the StauntonRiver watershed, basing his field determination on the evidence of stumps, it is known that narrow gauge railroad track was laid up the watershed for logging. Perhaps the loggers took downed trees and/or dead chestnuts which would not have left significant evidence of removal.

- It is of great interest that both the Pond Ridge and MoormansRiver areas of the park were the most impacted park areas by the rains of Hurricane Fran in 1996. Gullies 8' deep were cut into the slopes above the North Branch.

- Compilation of the known and identifiable landowners remaining in the park in 1936 (104 owners out of 203) from R.A, records and cross-indexed with the park land records shows that the average owner had a 74.72 acre tract. This size multiplied by the total of original resident landowners would indicate that 15,467acres of the park was originally owned by residents (8.95% of the park total).

- "Summary Statement concerning Families in the Shenandoah National Park Area," Resource Management Records, Box 99 & Box 100

- These include Lariloba Mining Company, Madison Timber, Piedmont Copper Company, Eagle Hardwood Company, Alleghany Ore, Depford Company, Christadora Heirs, Fray & Green, Fray & Miller, J. D. & H. B. Fray, the Graves family, the Long family, John A. Alexander, and the Pollock family.

- Gregg, Sara M., "Uncovering the Subsistence Economy in the Twentieth-Century South: Blue RidgeMountain Farms," Agricultural History, Vol. 78, Issue 4, pp. 417-437.

- Beautiful Shenandoah: A Handbook for Visitors to ShenandoahNational Park (1937), p. 3.

- ShenandoahNational Park Statement for Management (March 8, 1976), p. 8.

- Ebert, James I. and Alberto A. Gutierrez, "Relationships Between Landscape and Archaeological Sites in ShenandoahNational Park: A Remote Sensing Approach," Bulletin of the Association for Preservation Technology, Vol. XI, No 4, 1979, p.70.

- Conners, John A., ShenandoahNational Park: An Interpretive Guide, Blacksburg, Virginia (1988), p. 90.

- Some of the most famous photographs historically used to demonstrate the erosion caused by previous “poor farming practices” in the Blue Ridge are, in fact, showing scenes downslope from the then recently completed construction of the Skyline Drive.