Part of a series of articles titled The Oneida Carry.

Article

A Timeline History of the Oneida Carry

National Park Service

For thousands of years the ancient trail that connects the Mohawk River and Wood Creek served as a vital link for people traveling between the Atlantic Ocean and Lake Ontario. Travelers used this well-worn route through Oneida Indian territory to carry trade goods and news, as well as diseases, to others far away. When Europeans arrived they called this trail the Oneida Carrying Place and inaugurated a significant period in American history--a period when nations fought for control of not only the Oneida Carrying Place, but the Mohawk Valley, the homelands of the Six Nations Confederacy, and the rich resources of North America as well. In this struggle Fort Stanwix would play a vital role.

National Park Service

What is the Onieda Carry?

The Oneida Carry can be described as the largest portage in a system of rivers and lakes that can be used to traverse from the Atlantic Ocean to the Great Lakes. Headwaters of the Mohawk River flow south then eastward (past present day Rome, NY) becoming the main tributary of the Hudson River. At the point of entering of the Hudson, it becomes the only natural break in the Appalachian Mountains. The headwaters of Wood Creek flow south, then west (past present day Rome, NY), into Oneida Lake. Oneida Lake connects to the Oswego River, flowing northwest, which connects to Great Lake Ontario. The gap between the Mohawk River and Wood Creek became known as the “Oneida Carry” in reference to the local population of natives and to distinguish it from another large portage in New York near the Champlain Valley of a similar name. Other names referenced were the “Carrying Place,” “Trow Plat” (Dutch), and “Great Carry” in reference to the enormous distance one had to traverse.ii

The words “De-o-wain[m]-sta” have been, and are still, used in colloquial dialect to refer to the area in documentation since before the mid 1800s. Claims state that these are native words referring to “Great Carrying Place” or “Two Rivers Together,” dependent on the source.iii However, there is no source documenting these claims directly to Iroquoian or even Algonquian dialects. It is more possible that this phrase is a combination of French and Iroquoian words used together and recorded in translated conversations from earlier eras, then degraded over time. Example: “deux”= two (French) and “Úska” = together.iv

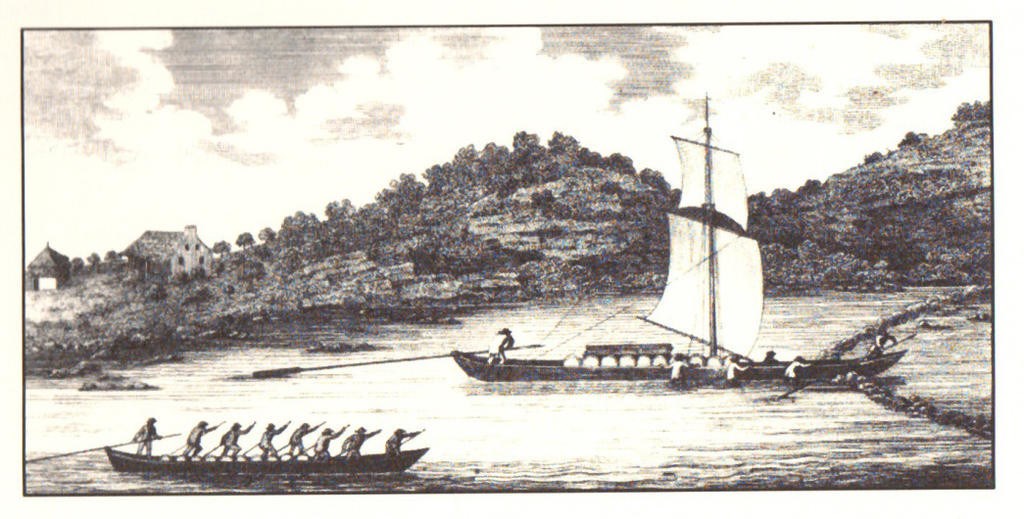

According to the first National Park Service report publishedin 1976, by historian John F. Luzader,the area: “Known as the Oneida Carrying Place, the portage was only a narrow trail across a low ridge in what is now central New York. In the 250 years after white men first used the portage, it became a funnel for fur trade, military activity and, eventually, settlement. Its strategic importance led finally to the construction of Fort Stanwix. The ridge lay between two major watersheds—the Mohawk River flowing eastward to the Hudson River and the Atlantic, and Wood Creek flowing westward to the Great Lakes by way of Oneida Lake and the Oswego River. During the spring thaws, whenboth watersheds were full, the distance across the portage was only 1 mile, while in the fall, after a drought, a man might have to walk [several] miles to find water deep enough to launch a bateau. The importance of this portage can only be realized whenone understands how poor the roads and trails were in colonial days. Most were mere ruts worn in the soil by travelers and were extremely difficult to negotiate on horseback, let alone by wagon. Rivers were the principal arteries of transportation and bateaus were developed to hold several tons of cargo. They could be propelled by three men paddling or, if the wind was right, with a sail. The Oneida Carry offered the second shortest route from the Atlantic to the Great Lakes. The St. Lawrence River, under French control until 1760, was the shortest.”v

Because of standardizations that took place in 1959 of the U.S. measurement system and international agreements between English-speaking countries, the length of a “mile” was standardized between the many countries and populations. Many of which were represented in records of early European Mohawk Valley history. In modern “international miles” the length of the portage road could safely be said to be six (6) miles long at its maximum, with a varying short distance dependent on flood stage of the Mohawk and Wood Creek near the various landings based on different points in history and conversions to modern units.vi

Evidence suggests that early native Americans moved into the vicinity around 800 C.E. Oral history suggests that the tribe we know today as the Oneida moved into or became the prominent force in the area circa the late 1500s.

From this point on, the words “carry” and “portage” will be used interchangeably. This is reflective of the historic writings of the day, but also the modern definitions of the words. These words will also be used to (unless otherwise noted) refer to “The Oneida Carry” in most instances, as there are so many different names used in the historic context.

LOC.gov/Pownall, Thomas, 1722-1805, artist & Sandby, Paul, 1731-1809, artist

1600s: European Colonialism

1614 – The Dutch established Fort Nassau, which is replaced by Fort Orange (Albany) in 1618, on the Hudson to control European trade into the Mohawk Valley with the Five Nationsand northern Hudson River. These forts replace a French structure that was built 1540 and then abandoned.vii

1626 – Approximately 7,250 beaver pelts and 800 otter were sent by other Five Nations tribes, through Mohawk middlemen to the Dutch for trade at Fort Orange.viii

1628 – Approximately 10,000 various pelts are brought for trade to Fort Orange.ix

1634 – The Dutch send a trade expedition of three men through the Mohawk Valley toward what is now modern Oneida, NY to report on native trade relations. They did this in response to fears that the Mohawk had made a truce with Canadian tribes to trade fur with exclusively with the French. This is thought to have happened because of an already badly depleted pelt supplying response to European demand. So the “truce” was not so much a way set up exclusive trade, but to allow the local animal populations recover enough so there would be ample supply for both food and trade.x

Upon arrival to the Oneida Castle village Harmen Meyndersten van den Bogaert recorded that the Oneida would exclusively trade beaver pelts with the Dutch at Fort Orange if the Dutch, “[will] give us[Oneidas]four hands of seawan [per pelt].” (Seawan is “wampum”) Bogaert recorded many other stops for trade along the way; noting: Oneidas presented him with several beaver pelts throughout his journey, the party's native guide presented knives, scissors, needles and an awl to a host chief at an Oneida village at one point. At several others, they were called worthless “scoundrels” because the gifts (including awls and bread) that were presented for trade were not as good as French items, brought into the area via the Oswego River to the north of Oneida Lake during previous encounters. These included shirts, coats, axes, razors, iron kettles, wampum, and many other items.xi

On the journey back to Fort Orange, Bogaert noted that the party exchanged bear pelts with Onondaga and elk with Maquas. This is the first recorded journey by a European party directly into the center of what would become Rome, NY and Oneida County. It should also be noted that at every large gathering Bogaert and his party arrived at, they were asked to fire their muskets and rifles. These trade items had not become prolific throughout Five Nations territory and were looked at almost as a novelty by the natives by Bogaert’s account.xii

However, the carry was not mentioned as being significant to his travels as such, as his main task was to visit the principle Oneida villages located beyond the western edge of the location and solidify Dutch alliances with them. It is possible that the area Bogaert passed early on and recorded as,“…many a stretch of flat land…where the water was knee deep; and I think we kept this day mostly the direction of the west and northwest,” could have been the carry.xiii But with no definitive European accounts before, no reliable native maps to compare the area to, and with his only map showing one continuous river from Fort Orange to the location of the main Oneida village south of the lake, it is hard to be certain.

National Park Service

1652 – 1654 – French Jesuit Priest Simon Le Moyne made six trips into Onondaga territory from New France on a mission of peace; visiting the shores of Onondaga Lake near the Five Nations’ central fire.xiv

November 18, 1655 – A missionary is erected in the heart of Onondaga territory on bequest of Fr. Simon Le Moyne to service the Iroquois and bring them French peace and religion; as had been done with, now French allies and Five Nations enemies, the Huron. Sainte-Marie-de-Ganentaa (or Ste. Marie among the Iroquois) becomes the first Catholic Church within Five Nations territory to offer all of the most significant sacraments of the faith. It is considered a success with schools being erected, Jesuits being sent throughout the heart of the Five Nations territory from their base at the mission church, and traveling down the Mohawk Valley to continue their mission by visiting the Dutch at Fort Orange.xv

1655 - 1658 – Within several of the principle villages (including Oneida Castle, the Kahnawá:ke Mohawk, and an unnamed Cayuga village) the Jesuit priests actually took up residence. Responses were varied. Some were taken prisoner after a short time; some established large parishes and were able to obtain converts. Most of these converts came from Mohawk communities.xvi

1658 – Sainte-Marie-de-Ganentaa is abandoned after threats by the Mohawk were made.xvii Reasoning over why becomes unclear in Jesuit records. They blame a combination of Dutch influence,poorly guided Mohawks for not seeing reason, and Onondagas for not seeing a supply party through to the mission quickly as Mohawks threatened war against Montreal. More likely it was a response to changing dynamics in the Five Nations’ communities as more converts retreated to Canada with missionaries and left their tribesmen in an unbalanced war against the Huron Indians, who too, had made peace with the French and began to convert to Catholicism. This threat to the mission base in the heart of their territory was probably a warning. Some missionary priests however, like Fr. Millet in Oneida territory, were asked or allowed to stay elsewhere.xviii

1664 – New Netherlands, a Dutch colony, becomes a British colony named New York. Many native trade outposts, run by the Dutch, become assimilated into the British system. However, nothing formal is established at the “Oneida Carry” area; leaving the space in between a tenuous border between New France and New York.xix

At this point in time, the Dutch trade network was still heavily reliant upon natives coming to established posts, like Fort Orange, to trade goods. Although this was more regulated and fairer in most instances than the French system, in which merchants were sent out among native villages to collect and trade goods, it was less profitable. As the British began to take the reins from the Dutch, they began to pay more for items like pelts at these outposts as wells as send out merchants. This began to leave the French not only with a disadvantage, but with many complaints about British fair trade practices.xx

1693 – It is thought that many of the Five Nations, including the Oneida, received their first formal exposure to Protest religious doctrines as a missionary from the Dutch Reformed Church of Albany returns from an excursion throughout New York (including the Mohawk Valley) stating that he had converted 200 in his journey.xxi

1700s: Colonial Expansions & Wars

July 10, 1702 – Two native tribes, one Miami the other possibly Seneca, formally petitioned Colonial Governor Cornbury to clear the area to become the portage road of trees and a proper path be marked; to make it easier to carry canoes. This request was granted and the governor sent formal escorts with the natives to see this work done.xxii This is also around the time Queen Anne's War (a fourth in a succession of Colonial British and French wars), becomes prominent. It is possible that the governor supports the idea of land clearance in case there is a need for British troops to transport themselves through the area without hindrance, or to keep the natives happy and/or relatively “pro-British.”

April 18, 1705 – The area surrounding the carry is referred to as the “Oriskany Patent,” or land grant of 32,000 acres, and was given to five persons; Peter Schuyler, George Clarke, Thomas Wenham, Peter Fauconnier, and Robert Mompeson. It was divided into two parcels. One of the parcels was described as having bounds that “commenced at the junction of Oriskany creek with the Mohawk and ran up that creek a distance of four English miles, and back into the woods a distance of two English miles on each side of the stream.” The second parcels boundaries “were on both sides of the Mohawk River commencing at Oriskany Creek and running up the river a distance of two miles on each side to the Oneida Carrying Place; thence of the same with of each side of the Indian path which leads over the carrying place between the Mohawk River and Wood Creek to a swamp.” xxiii This swamp was land that is now part of west Rome, NY and the Sand Plains area. This reference is the first one referring to the portage as the “Oneida Carry;” the name most commonly used today.xxiv

1713 – 1722 – Tuscarora Indians, an Iroquoian speaking tribe, move to the area surrounding the carry after a war in the Carolinas against colonists. They petition the Oneidas for land and are accepted as the “Sixth” of the Five Nations.xxv

1720s – Forty seven separate complaints are received by British colonial officials from European merchants accusing the Oneidas of taking advantage of their location along the carry route to exploit European trade.xxvi

1727 – Fearing that the French could take advantage of the lucrative fur trade accessible by the water route, and lure away the native population that did business with them, the British built a small fortified trade post at the mouth of the Oswego River at Lake Ontario. This blocked access to the interior of the New York Colony. It was followed by stockades at either end of Oneida Lake.xxviii

1731 – A Protestant minister named Domine Petrus van Driessen reports to the Classis of Amsterdam that two-thirds of the Oneida had converted to Christianity. By a decade later, Oneidas are no longer traveling to Albany for Protestant services, but receiving them in German Flatts, 40 miles to the east of the carry.xxix

1750s – 1770s – Many European suttlers locate themselves out along the Oneida Carry to maintain trade with natives in the area. As the British military locate to the carryover the next decade in they become a fixture.xxx The most prominent of these families was the Rueff/Roof family, who moved to the area in 1759. xxxi Patriarch John purchased his land (on the grounds adjacent to the southwest bastion of the fort where a modern day hotel is located) from one Oliver De Lancey; who at this time held the eastern most portion of the Oriskany patent.xxxii The Roofs ran an inn, tavern, and hauling business catering to the many European and native merchants traveling the Carry. They stayed there until July of 1777 until several neighbor girls, from families living near the abandoned Fort Newport on Wood Creek, were murdered in early raids by British allied Indians.xxxiii

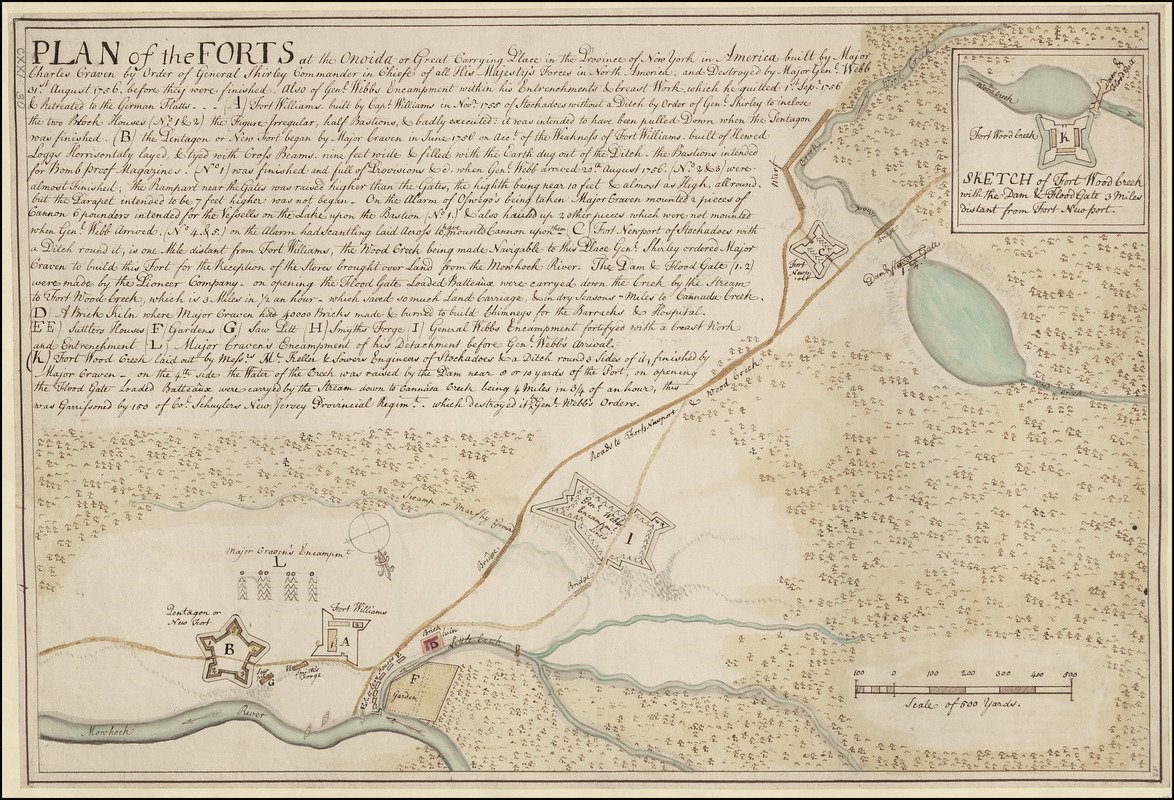

1755 – In response to French threats as another colonial war (the French and Indian) erupted, William Shirley, Major General of Royal Forces in North America, directed Captain William Williams to clear the road and rivers from Wood Creek till Oneida Castle. From headquarters established near the carry that summer, Shirley conducts business managing the campaigns against Niagara, Oswego, and securing the Great Lakes in the name of Great Britain. He calls this area “Oneida Station. “On October 29thof that year he orders Williams to erect a fort that could contain 150 men and to rebuild the portage road between the Mohawk River and Wood Creek, complete with bridges where needed. This becomes known as Fort William[s]. A second fort was ordered to be erected simultaneously at the upper (high flood) landing of Wood Creek which is to be known as such, but is then called Fort Bull. At any given time there were 500 to 1,000 British troops located in the area on a permanent basis. Saw-pits, brick kilns, a forge, and a garden were erected by these soldiers. Many more soldiers passed through on various expeditions.xxxiv This is only the first of several military occupations of the carry to follow, as its strategic importance to operations is realized.

circa 1755 – William Livingston, member of a prominent New York colonial family, described a journey across the entire water system during a raid into French territory (including the Oneida Carry) in this manner:

Oswego, along the accustomed route, is computed to be about 300 miles west from Albany. The first sixteen, to the village of Schenectady, is land carriage, in a good waggon road. From thence to the Little Falls of the Mohawk River, at sixty five miles distance, the battoes [sic.] are set against a rapid steam; which too, in dry seasons, is so shallow, that the men are frequently obliged to turn out, and draw their craft over the rifts with inconceivable labour. At the Little Falls, the portage exceeds not a mile: the ground being marshy will admit of no wheel-carriage, and therefore the Germans who reside here, transport the battoes in sleds, which they keep for that purpose. The same conveyance is used at the Great Carrying Place, sixty miles beyond the Little Falls; all the way to which the current is still adverse, and extremely swift. The portage here is longer or shorter, according to the dryness or wetness of the seasons. In the last summer months, when the rains are most infrequent, it is usually six or eight miles across. Taking water again, we enter a narrow rivulet, called the Woodcreek, which leads into the Oneida Lake, distant about forty miles. This stream, tho' favorable, being shallow, and its banks covered with thick woods, was at this time much obstructed with old logs and fallen trees. The Oneida Lake stretches from east to west about thirty miles, and in calm weather is passed with great facility. At its western extremity opens the Onondaga [Oswego] River, leading down to Oswego, situated at its entrance on the south side of Lake Ontario. Extremely difficult and hazardous with rifts and rocks; and the current flowing with surprising rapidity. The principal obstruction is twelve miles short of Oswego, and is a fall of about eleven feet perpendicular. The portage here is by land, not exceeding forty yards, before they launch for the last time.xxxv

March 27, 1756 – The most westerly fort along the carry, Bull, is destroyed in a French raid. The officer in charge of the raid, De Lery records:

During the French raids into the Mohawk Valley (that began with the capture of Fort Oswego/Choueguen, one French participant wrote: “From Fort Bull to Fort Williams is estimated to be one league and a quarter. This is the carrying place across the height of land. The English had constructed a road there over which all the carriages passed…It was to be intermediate between the two forts, having been located precisely on the summit level.”xxxvi After the raid was over a larger stronger fort was built to replace the original almost immediately. This fort has a dam built near it to help cut time floating from Wood Creek to Oneida Lake. One was also built even further up Wood Creek’s waters called Fort Newport. This too had a dam and its location allowed travel time from one end of the carry to the next to be cut. A pentagon style fort that became known as “Craven” was built further downstream from Williams, allowing the latter to focus on safe transport of goods and people along the carry as opposed to guarding the river.xxxvii

August 1756 – Shirley is replaced by Col. Daniel Webb in supervising British operations at Oneida Station,and decides to focus efforts elsewhere upon learning of British defeat at Fort Oswego. On August 31, 1756 all the British works and troops occupying the portage road are ordered destroyed and they retreat to German Flatts. Subsequently, the French conduct several raids past the abandoned works and destroy settlements in the German Flatts area. Many of the Six Nations members are left unimpressed and angry at the abrupt abandonment.xxxviii

National Park Service

Summer 1758 – Gen. James Abercromby became the British lead of operations in New York. Worried about how he will support and protect his troops trying to take Fort Ticonderoga, north of Albany and Lake George, he ordered one Brigadier Gen. John Stanwix to build a newer larger fort in the location of the carry and has British Indian Superintendent William Johnson secure Oneida favor before having the orders carried out. Johnson promised the Oneidas, “plentiful and cheap trade,” as well as the fort’s destruction at the end of the conflict. xxxix

August 1758 – Although several engineers are sent along with Stanwix to oversee the refortification, one is replaced with Capt. Williams who had seen the prior forts constructed. Of the 5,000 plus men sent to construct this new fort, half are struck ill and other must attend to regular camp duties, leaving approximately 3,000 ready for work.xl

August 26, 1758 – The first log of the new fort is laid. The foundation was completed ten days later. Over the course of the next several months, progress was made slowly and surely as men are drained and resupplied from the work force to engage in expeditions against the French. In November, the new fort, soon to be known as “Stanwix,” was completed and defendable. For the rest of the war, it serves as a waystation for troops heading to British expeditions further west.xli

1760s – The Oneida village of Oriska[ny]is established to the east of the carry in response to the British occupation. Villagers sell food, haul goods, and trade merchandise with Europeans crossing the carry toward the fort. Out of the 90 or so residents, only half are actually Oneida. The others are European merchants who moved to the area to capitalize on the opportunity.xlii

1761 – Reverand Samuel Kirkland, a young Presbyterian minister from Connecticut, begins preaching amongst the Seneca and Oneida.xliii Around 1764, he moved to the principle Oneida Village to the west of the carry. He stayed for many years and became an influential figure; becoming the spiritual advisor of respected chief Skenandoa. This relationship helped to convince the majority of Oneida and Tuscarora to ally with the American cause as the Revolution descended on the Mohawk Valley.xliv

1763 – At the conclusion of the French and Indian War, Fort Stanwix still stood, serving as a mark of the British Empire in native territory. It had not been leveled as previously promised. Instead, it is more heavily fortified and repaired.xlv

November 1768 – An Indian congress is called together at Fort Stanwix by Sir William Johnson. This is done for several reasons: To calm Six Nations’ fears that the British pose a true imperial threat to them as outposts farther west have already been dismantled or abandoned. To assure them of the continual need for peace as other native tribes further west enter into warfare against other British outposts that hadn’t yet been removed. And to establish a proper boundary between colonial European settlement land and ALL native lands in British North America so that everyone could go back to trade and exchange in peace. Johnson is supposed to reinforce an arbitrary line drawn by royal authorities in 1763, but negotiates away more native land than he is authorized to.

The new boundary in the north begins at Fort Stanwix and pushes much farther to the west than originally intended; opening much more native land in New York and Pennsylvania for settlement than most tribes were willing to accept.xlvi

National Park Service

Late 1700s: American Revolution & Treaty Signings

1776 – A trading post was established by order of Gen. Philip Schuyler at Fort Stanwix. Schuyler is tasked with heading the Northern Department of the Continental Army under Gen. George Washington’s command and sees the value in maintaining good relations with the natives. This is especially important as the new United States enter full blown warfare against Great Britain. He requests local merchants, Congress, and other states to provide woolen goods. This is to ease Oneida tension from a recent raid by British allied Mohawks into their territory looking for Samuel Kirkland; the protestant missionary with patriot sentiments and connections. Schuyler warns all that if clothing is not provided “Indian interest will be lost.” Soldiers, officers, and other passer-by also trade at this post for fur and blankets.xlvii As Schuyler issued orders for a fort to be constructed on the grounds of Fort Stanwix, he ordered a room inside to be used solely for such goods. Rum, shirts, pipes, blankets, beef, and bread were all acquired as gifts or provisions for Indian use by 1777. Schuyler then sent word to Samuel Kirkland that the post was ready for business.xlviii

June 8, 1776 – A letter was sent to the President of the Continental Congress by Gen. Schuyler recommending the area of the carry be occupied by Continentals and that the Indians be notified of their intention to do so. Three days later, Schuyler sent word to Washington that plans had already been arranged in secret to carry this out. A week later, Congress sent word to Schuyler to begin the reoccupation as soon as Washington sent proper orders. Washington complied, Schuyler called an Indian Council at German Flatts, and approximately 1,000 men were sent to the Oneida Carry under the direct authority of Colonel Elias Dayton of the 3rdNew Jersey Regiment.xlix

July 23, 1776 – Dayton and his men arrived at their destination without stirring the local population. He and engineer Nathaniel Hubbell are tasked by Schuyler with choosing the best location to build a new fort if the remains of old Fort Stanwix are unusable. Upon selection of the latter, work is commenced in mid-July.l

August 15, 1776 –The new American occupied fort is considered usable and dubbed “Fort Schuyler,” after its patron. Artillery have already been posted at the site and Schuyler writes immediately to Gen. Horatio Gates, letting him know that the Continental troops he has placed there will be well protected if British soldiers from the outpost at Oswego try to venture an attack.Work continues throughout the winter and spring until the fort can readily hold a garrison of about 500 men without issue.li

March 29, 1777 – A garden is ordered to be fenced in by Colonel Peter Gansevoort, now in command of Fort Schuyler. The fence runs from the swamp area, just south of the fort, to the Mohawk River, to the southeast. His intention is to have hay, grass, and vegetables for the garrison grown within the area fenced off. In spring of 1778, he repeats the order to plant vegetables.lii

May - June 1777 – Col. Gansevoort received an order from Gen. Schuyler and Gen. Gates pertaining to contact with the native population. On May 29, 1777 “Presents” including black powder are to be distributed to the Oneidas via their interpreter, James Deane from the garrison’s commissary. On June 9, 1777, orders are issued that no one, aside from official Commissioners of Indian Affairs are to speak directly to the Oneidas or any other native group. If transactions must occur, they are to be kept to a minimum, recorded on paper, and sent directly to Gen. Schuyler.liii

National Park Service

June - July 1777 – An expedition led by, Brigadier Gen. Barry St. Leger, is begun at the mouth of the St. Lawrence River, through Lake Ontario, the Oswego River, to Oneida Lake. Under his command is a combined force of about 2,000 British soldiers, German mercenaries, Mohawk, Seneca, Great Lakes Indians, and displaced New Yorkers of European descent. Their goal is to swarm the Oneida Carry and Mohawk Valley and then unite forces with British Gen. John Burgoyne; whose army is rapidly approaching the intended target of Albany, NY via the Champlain Valley. As St. Leger’s forces approach Fort Schuyler, now under command of Col. Peter Gansevoort of the 3rd New York Regiment, their progress is hindered by trees felled across Wood Creek by the fort’s garrison and local militias. In late August, the efforts of the combined British forces fail, and they retreat back to Canada. This is the result of loss of morale due to a failed attempt to save the fort by local militia forces in the Mohawk Valley which resulted in much loss of life on both sides and loss of supplies and word that more continentals, led by Gen. Benedict Arnold were soon to arrive from Albany, NY.liv

March 21, 1778 – A letter is sent to Col. Gansevoort from the Marquis de Lafayette stating orders have been granted to him to begin construction of a new fort, to be situated 16 to 20 miles west of Fort Schuyler in Oneida territory for exclusive use by the Oneidas. The Marquis states he will be relying on the Tryon County Militia force to aid in its construction and wishes the Fort Schuyler garrison to provide the tools.lv

April 28, 1778 – “Gifts” are sent to replenish the garrison store by The American Commissioner of Indian Affairs at Albany. Orders are placed in “Conspicuous parts” about the fort stating all garrison members should refrain from using these items or dealing with Indian traffic in any way, for fear of severe punishment.lvi

April 18, 1779 – An expedition, led by American Col. Goose Van Schaick of the 1st NY Regiment from Fort Schuyler leaves to Wood Creek, up the Oswego River, and into the heart of Onondaga territory. The purpose of this expedition is to counter raids conducted by outcast European New Yorkers and Indians the previous year that left the Mohawk Valley in ruins. However, natives that have remained neutral throughout the war, such as the Onondaga, become the focus of the Van Schaick’s operation. Onondaga Castle, their principal village, is destroyed, many are killed, and hundreds of others are left without supply. The American troops return two weeks later without one man lost. Many of the Onondaga flee to Oneida territory as refugees.lvii

May 27, 1781 – Final orders were sent to Congress and the 2nd NY Regiment (now occupying the fort) stating withdrawal should be immediate. During the course of spring, floods and fire had made the fort nearly uninhabitable. Troops are removed to Schenectady and Albany and the American Revolutionary military occupation on the carry comes to an end.lviii

July 1783 – George Washington touredthe Oneida Carry after the close of the American Revolutionary War. New York State Gov. George Clinton, Alexander Hamilton, and one Mohawk Valley resident accompanied him.lix After his visit, Washington purchased large land holdings just to the south of the old fort and in other parts of New York.lx

September 1784 – Delegates from the Six Nations, State of New York, and U.S. Government begin to gather at the ruins of Fort Schuyler to conduct a treaty to bring peace to New York (The 1783 Treaty of Paris disregarded all Indian nations involved in the war). Amongst the New York State representatives is Governor George Clinton. Amongst the federal representatives are James Monroe, James Madison, Arthur Lee, Oliver Wolcott, the Marquis de La Fayette, and General Richard Butler. After an upheaval is caused by state reps trying to conduct business with Six Nations representatives, such as Mohawk leader Joseph Brant, without prior permission they are removed from the site before the end of September. Suttlers and alcohol are ordered removed as well.lxi

October 1784 – After previous interruptions, the Federal authorities dictate a treaty that stated all Six Nations were to be recognized as separate sovereign nations by the United States. The Oneida and Tuscarora were to be considered allies for their cooperation and actions throughout the war; but the other four nations were to be admonished, all were to be given peace, and land was to be ceded beyond the 1768 boundary in exchange for this. As a result, reservation lines were drawn to establish where these new “nations” were to live beyond the border of the carry. This treaty was signed on October 22, by all federal and Six Nations representatives present, but only the United States ratified it (in 1785). In the years to follow, several other treaties were signed on the same grounds by federal, state, and native authorities.lxii

New York State History Museum

Late 1700s/Early 1800s: Westward American Expansion

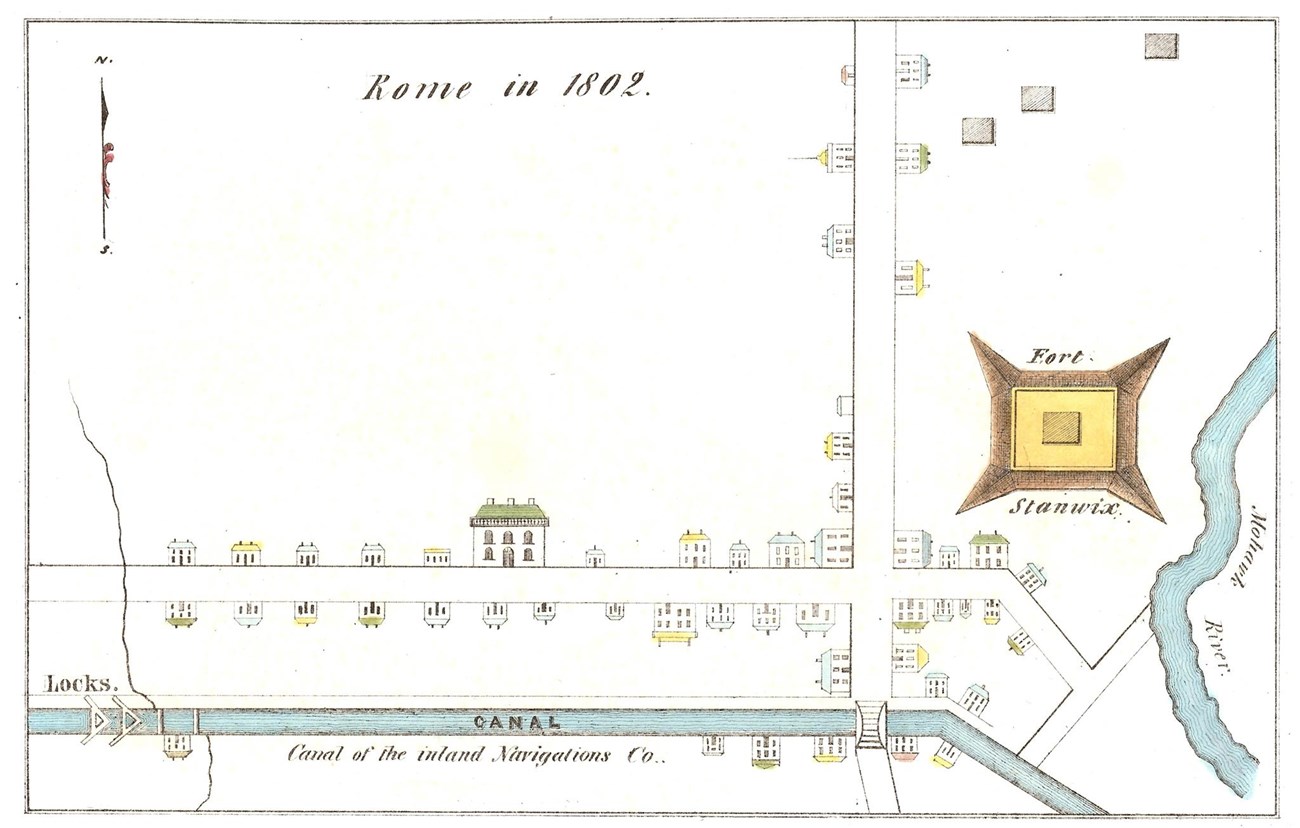

March 1786 – The State of New York surveys 697 acres of land from the Oriskany Patent confiscated from descendants of the De Lancey family that had been pro-British during the Revolution. This included the land surrounding the carry and Fort Stanwix/Schuyler. It was sold in an auction in New York City to one Dominick Lynch for £2,500; this land became the center of a village that would be known shortly as “Lynchville” and then “Rome.”lxiii

1794 – A blockhouse was built by the U.S Military on the grounds of the former Fort Schuyler to store supplies in case of emergency. It is used until about 1810 and then abandoned.lxiv

Early Spring 1796 – Inland Lock Navigation Company began construction on a canal between the Mohawk and Wood Creek. “Their object was to effect a junction of the waters of the Mohawk with those of Wood creek, by means of a canal between the respective landing-places.”The recorded length from the Mohawk to Wood creek at this period was “two miles and three chains.” (This distance was recorded at high flood stage at the upper landings in the spring). About expenditures and modifications to the land, the report made by the Inland Lock Navigation Co. itself states that: “Large sums of money have already been expended by the company in removing trees out of the bed of the river Mohawk and Wood Creek, which had either accidentally fallen therein from its banks or were intentionally cut down and drawn therein for the purpose of clearing the adjacent ground…The company have expended in improving the bed of the Mohawk, in straightening and improving Wood creek, in completing locks and canals at Fort Schuyler, the canal and locks at Little Falls, and upon the canal at German Flats, about $209,357.”lxv

Christian Schultz’s “Travels on an Inland Voyage” (1810)

July 12, 1810 – New York Governor Dewitt Clinton arrives in the area to spend two days on a tour arranged by his chief engineer and surveyor Benjamin Wright. His goal was to see if the land is suitable for expansion of the existing canal system and bolster New York’s expanding industrial revolution by opening the western frontier to new markets. He made several notable observations about the area including:

-

“Rome is on the highest land between Lake Ontario and the Hudson, at Troy. It is 390 feet above the latter; 16 miles by land and 21 by water from Utica, and 106 miles by water from Schenectady. It is situated at the head of the Mohawk River and Wood Creek, that river running east and the Wood creek west. You see no hills or mountains in its vicinity; a plain extends from it on all sides…Its excellent position on the [Inland Lock] Canal, which unites the Eastern and Western waters; and its natural communication with the rich counties on the Black River, would render it a place of great importance, superior to Utica, if fair play had been given to its advantages.”

-

“The site of Fort Stanwix or Fort Schuyler is in this village. It contains about two acres, and is a regular fortification, with four bastions and a deep ditch. The position of protecting the passage between the lakes and the Mohawk River. It is now in ruins, and partly demolished by [Dominick] Lynch; its proprietor. Since the Revolutionary War a block-house was erected here by the State, and is now demolished. About half a mile below the Fort, on the meadows, are the remains of an old fort, called Fort William[s]; and about a mile west of Rome, near where Wood Creek enters the Canal, there was a regular fort, called Fort Newport. Wood Creek is so narrow that you can step over it.”

-

“Fort Stanwix is celebrated in the history of the Revolutionary War, for a regular siege which it stood. And as this and the battle of Oriskany are talked of all over the country, and are not embodied at large in history, I shall give an account of them, before they are lost in the memory of tradition.”

-

“The [Mohawk] river is about 120 miles in length, from Rome to the Hudson. Its course is from west to east. The commencement of its navigation is at Schenectady. It is in all places sufficiently wide for sloop navigation; but the various shoals, currents, rifts, rapids with which it abounds...render it difficult even for bateaux…The river is only good as a feeder.lxvi

1813 – The Rome Arsenal constructed near the remains of Fort Newport on the Wood Creek side of the Carry in now, Rome, NY. This is a military complex used to support operations in the Fort Oswego area throughout the War of 1812. It is used a supply depot throughout the war and transitions to a recruiting and training complex after the conclusion and straight through till1873. It supplants a blockhouse built on the remains of Fort Stanwix/Schuyler by the U.S. Military in 1794.lxvii

1817 – The first shovelful of earth is turned on construction of the Erie Canal in Rome, NY. This takes place on the westerly end of the Oneida Carry near the location of former location of Fort Bull/Wood Creek (near the present day location of the intersections of NYS Routes 69, 49, and 46).lxviii

1825 – The Erie Canal is completed and ceremonially opened for business by Governor Dewitt Clinton in a ceremony known as “The Wedding of the Waters.”lxix

1839 – The Black River Canal, which connected the foothills of the Adirondack Mountains to the Erie Canal system is finished. At 35 miles long, its southernmost terminus is at Rome, NY near the intersections of modern-day Black River Boulevard and East Dominick Streets; parallel to the eastern wall of the old fort remains.lxx

The Historic Landscape

On the west and northwest, the soils are loamy clays, sands, and some shale that contributed to many swampy bogs to the south of the carry and sand plain or pine barren areas, like those that can be found sur rounding Wood Creek upon its exit from modern Rome, NY and along the eastern shore of Oneida Lake. lxxii This is a unique habitat that, today, is very hard to find in North America and would have been distinct in its appearance compared to the surrounding forests. This would have looked like an odd mash of sand dunes, beach shore, and deciduous/coniferous forests. Around Wood Creek, there would have been many aquaticplants (such as sedges and sea grasses) more similar to those found in northern seacoast mixed in with a variety of trees from different northern growth zones (such as white pine, hemlock, white, red, and black oaks, white and yellow birch, pine pitch, wild black cherry, and sassafras).lxxiii

Mannevillette Elihu Dearing Brown, 1854

In swampier bog and flood areas toward the south and southeast, red and silver maples, elms, basswoods, red ash, tulip trees, cottonwoods, and tupelo trees could be found in the mix. Various shrubs and grass, including honey suckle, Canada violets, goldenrod, wild sarsaparilla, and partridge berry, would be found along with an exhaustive list of ferns, grasses, and other plants native to the “Austral” growing region of North America.lxxiv

Just on the north and eastern end of the carry, underlying bedrock and soils are mostly shale and clay. lxxv Trees such as white pine, various oaks, beeches, birches, tamaracks, and others form to make the foothill forest of the Adirondacks and hardwood forests of the western Mohawk Valley.lxxvi

Looking at the area surrounding the fort during the time of the American Revolution one would have seen: To the north, an area cleared by the British military during the French and Indian War period and those hardwood forests sloping upwards towards the foothills of the Adirondack Mountains. To the east, a clearing that extended to a freshwater stream about 100 yards, beyond that a mixture of hardwood and swamp forests leading to the banks of the Mohawk River.

To the south, the portage road, passing through a cleared field that lead from east to west. In the southeast view would have been a fenced military garden on the banks of the stream. In the southwest view would have been grouping of military out buildings, including: a hospital, blacksmith shop, and stable area. An “Indian House” was also in this area. A small arrangement of buildings belonging to the Roof family (homestead, barn, outbuilding, etc.)would have also been visible. Beyond those would have been mixed swamp forest and sand plains. To the west would have been a view of the portage road leading to Wood Creek through a cleared field. Beyond that was a sand plain environment.lxxvii Wandering as freely as their owners would allow would have been livestock belonging to the colonial settlers, the American military, and to the private soldiers.lxxviii

National Park Service

Historic Fauna

National Park Service

Birds in the Oneida County area had been studied extensively throughout the late 1700s to early 1900s. In 1977, after compiling historic data and records, there were 289 native species known to Oneida County. One of the more notable species is the wild (passenger) pigeon, which has gone extinct and were recorded as an easy meal for the soldiers of Fort Schuyler in the time of the Revolution (they netted them on walls). There are several pigeon bones in the park collection. Others include the wild turkey, which was almost eliminated through hunting and development by the mid-1800s, the peregrine falcon, and bluebird. Mockingbird, titmouse, and Carolina wren (although native) spread further into the area as trees were cut from the forests as they survive on forest perimeters and lowlands.

Amphibians and reptiles could be found as well including the bullfrog, wood turtle, box turtle, copperhead snake, timber rattlesnake, and eastern massasauga rattlesnake (or swamp rattler). Because of the many fish brought to stock ponds in the 1800s, it is difficult, if not impossible to determine what species of fish are specifically native to the Mohawk River, Wood Creek, and Oneida Lake. However, the recorded Atlantic salmon migrations to Oneida Lake stopped in 1856 as further development along the lake began. It has also had a consistent record of walleye pike, which were restocked as their numbers dropped. There are about a dozen walleye bones in the park collection. Brook trout were recorded in many of the streams flowing into the lake.lxxix Northern Pike, perch, large and small mouth bass, and sunfish would have been found throughout the lakes, streams and rivers of the modern New York area, including the Mohawk.lxxx

National Park Service/Ranger Dan U.

There are many mammals that have been recorded throughout the area surrounding the carry. Some of the species that helped to contribute to the historic growth of the area, through the fur trade, include: beaver, rabbits, fox, squirrel (red), white-tailed deer, and mink. Wolves, elk, wolverines, fisher, and marten numbers declined rapidly or became extinct throughout the 1800s as trappers flooded the area. Beaver are the best example of a species on the brink because of trapping and hunting as their numbers were nearly wiped out in the mid to late 1600s and again in the 1700s (dependent on New York region).

Mountain lion and bobcat were recorded throughout New York, however rarely because their range can be large. Most sightings in the in the early 1800s took place in northern most reaches of Oneida County’s borders. There is debate about whether or not moose may have occurred in northern Oneida County during the 1700s and years prior.lxxxi It should be noted that the forested lands that both the cats and moose require would have extended down into the area of the carry prior to its development.

The 1600s era Dutch man, Bogaert, who became the first European to record his journey through the area in 1634, stated that he was fed white hare, beaver, dried and fresh salmon, bear bacon, and venison. He also saw (living or pelts) elk, beaver, bear, otter, mountain lion, and deer.lxxxii

ii Wagner, D.E. (Ed.). (1896).Our County and Its People: A Descriptive Work on Oneida County. Boston: The Boston History Company

iii Ibid, Wagner (1896).

iv “Oneida Language Tools.” (2011, September15). University of Wisconsin Green Bay. http://www.uwgb.edu/oneida/index.html

v Luzader, John F. (1976). Construction and Military History of Fort Stanwix: 1758 TO 1777. Washington, D.C.: Office of Park Historic Preservation National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior

vi McColl, R..W. (2005). Encyclopedia of World Geography. Volume 1.

vii Graymont, Barbara. (1972). The Iroquois in the American Revolution. Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Pressviii Harris, Steve.“A Chronological Outline of the Colonial Fur Trade.” Fort Stanwix NM Research Archives.

ix Ibid,Harris.

x The History of Oneida County: Commemorating the Bicentennial of Our National Independence. (1977). Utica, NY: Oneida County Historical Society. Lenig, Donald. “The Oneida Indians and Their Predecessors”

xi Sleeman, G.M. (Ed.) (1990). Early Histories and Descriptions of Oneida County New York. Utica, NY: North Country Books

xii Ibid, Wagner (1896)xiii Ibid, Sleeman (1990).

xiv “Simon Le Moyne.” (2011, September 15). Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online.http://www.biographi.ca/index-e.html

xv Gilmary, John S. (1857). Henry De Courcy. The Catholic Church in the United States, Second Edition Revised. New York: Edward Dunigan and Brother, (James B. Kirker)

xvi Ibid, Gilmary (1857).

xvii Ibid, “Simon Le Moyne.” (2011, September 15). Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online.

xviii Ibid, Ibid, Gilmary (1857)

xix Ibid, Graymont (1972).

xx O'Callaghan, Edmund B. (1854). Documents Relating to The Colonial History of the State of New York. Albany: New York State Archives.

xxi Ibid. Lenig (1977).

xxii Ibid, O'Callaghan (1854).

xxiii Ibid, Wagner (1896).

xxiv Wagner, D.E. (1881). “Fort Stanwix and Bull and Other Forts at Rome,” Transactions of the Oneida Historical Society at Utica, Volumes 1-5.

xxv Ibid. Lenig (1977).

xxvi Ibid, Luzader (1976).

xxvii Ibid, O'Callaghan (1854).

xxviii Ibid, Luzader (1976).

xxix Ibid. Lenig (1977).

xxx Ibid, Luzader (1976).

xxxi “Johann Nicholas Roof.” (1841, October 2). Rome, NY: Rome Daily Sentinel, Obituaries

xxxii Ibid, Wagner (1896)

xxxiii Lowenthal, Larry. (Ed.). (1983). Days of Siege: A Journal of the Siege of Fort Stanwix. Eastern Acorn Press

xxxiv Ibid, Luzader (1976).

xxxv Livingston, William. (1757). A Review of the Military Operations in North America. London. http://www.archive.org/stream/cihm_40020#page/n49/mode/2up

xxxvi de Léry, Joseph Gaspard Chaussegros. (1927) Les journaux de campagne de Joseph Gaspard Chaussegros de Léry; Québec: Imprimeur du Roi. vol. 192. Pgs 391-393or “Joeseph de Lery.” (2011, September 15). Canadian Archives. http://collectionscanada.gc.ca/index-e.html

xxxvii Ibid, Luzader (1976).

xxxviii Ibid, Luzader (1976).

xxxix Ibid, Luzader (1976).

xl Ibid, Luzader (1976).

xli Ibid, Luzader (1976).

xlii Glattharr, Joeseph T., et. al. (2006). Forgotten Allies: The Oneida Indians and the American Revolution. New York: Hill and Wang.

xliii Ibid, Graymont (1972).

xliv Ibid. Lenig (1977).

xlv Ibid, Luzader (1976).

xlvi Ibid, Luzader (1976).

xlvii Ibid, Glattharr (2006).

xlviii Torres, Louis. (1976). Historic Furnishing Study. Washington, D.C.: Office of Park Historic Preservation National Park Service, U.S.Department of the Interior

xlix Ibid, Luzader (1976).

l Ibid, Luzader (1976).

li Ibid, Luzader (1976).

lii Gansevoort, Peter. (1777-1778). Military Papers, 3rdNew York Regiment, Fort Schuyler.Albany: New York Archives Collection.

liii Ibid,Gansevoort.

liv Berleth, Richard. (2009). Bloody Mohawk. Hensonville, NY: Black Dome Publishing.

lv Ibid,Gansevoort (1778, March 21).

lvi Willett, Marinus. (1778, April 28). Garrison Orders, 3rdNew York Regiment, Fort Schuyler.

lvii Ibid, Berleth (2009).

lviii Ibid, Luzader (1976).

lix “Wood Creek History.” (1897, February 3). Rome Daily Sentinel. New York State Archives Report.

lx Ibid, Wagner (1896).

lxi Manley, Henry S. (1932). The Treaty of Fort Stanwix, 1784. The Rome Sentinel Company.

lxii Ibid, Manley (1932).

lxiii Ibid, Wagner (1896).

lxiv Ibid, Luzader (1976).

lxv Schuyler, Philip. (1798). Second Report of the Western Inland Lock Navigation Company.; “Canal Enlargement in New York State.”(1909). Buffalo Historical Society Publications, Vol.

lxvi Campbell, William W. (1849). Dewitt Clinton. “Private Canal Journal, 1810.” The Life and Writings of Dewitt Clinton. (2011, September 15) University of Rochester. http://www.history.rochester.edu/canal/bib/campbell/contents.html

lxvii “Rome Arsenal.” (2011, October 6). New York State Military Museum and Veterans Research Center. http://dmna.state.ny.us/forts/fortsQ_S/romeArsenal.htm

lxviii Ibid, Wagner (1896). & The History of Oneida County: Commemorating the Bicentennial of Our National Independence. (1977). Utica, NY: Oneida County Historical Society. Larkin, Daniel F. “Three Centuries of Transportation”.

lxix Ibid, Wagner (1896) & Ibid, Larkin (1977).

lxx Ibid, Wagner (1896) & Ibid, Larkin (1977).

Tags

- fort stanwix national monument

- fort stanwix

- american revolution

- french and indian war

- native american history

- early american history

- european exploration

- transportation

- native settlements

- archeology

- archaeology

- revolution

- soldiers

- native american

- indigenous

- trade

- american indian

- new york

- mid-atlantic

Last updated: December 16, 2024