Last updated: December 3, 2022

Article

"A Splendid Young Soldier": Cpl. James Murray, Dwight D. Eisenhower, and the Korean War

Eisenhower Presidential Library

Dwight D. Eisenhower’s December 1952 trip to Korea was an important chapter in his presidency before it even started for many reasons. Perhaps chief among them is it signaled that as Commander in Chief Eisenhower would employ some of the same leadership methods he had used as Supreme Allied Commander in World War II. Whether it was June 5, 1944, and meeting paratroopers of the 101st Airborne hours before they dropped into Normandy or greeting U.S. soldiers in the cold wintry mountains of Korea in December 1952, Eisenhower’s leadership style was defined by making personal connections with those who knew best—those serving on the front lines of America’s wars.

Ike traveled to Korea in December 1952 to fulfill a campaign pledge he had made the previous fall, that if elected, he would travel to survey the scene in the Korean War. He made the over 10,000-mile journey in secret, arriving in Seoul on December 2. Ike spent his first day being briefed on the war by American and UN commanders. He also met for an hour with South Korean President Syngman Rhee. In Ike’s eyes, however, the main purpose of his visit was to spend time at the front with those doing the fighting. Using a L-19 “puddle jumper” plane, Eisenhower flew from unit to unit, spending time with Republic of Korea, United Nations, and United States forces. In the December cold, Eisenhower was given a green army issue parka, which is now part of the Eisenhower NHS museum collection.

Ike’s visit received an overwhelmingly positive response from those at the front, with one soldier in the British 1st Commonwealth Division noting, “If anybody can end [the war], General Eisenhower can. He’s the man to do it, sir.”

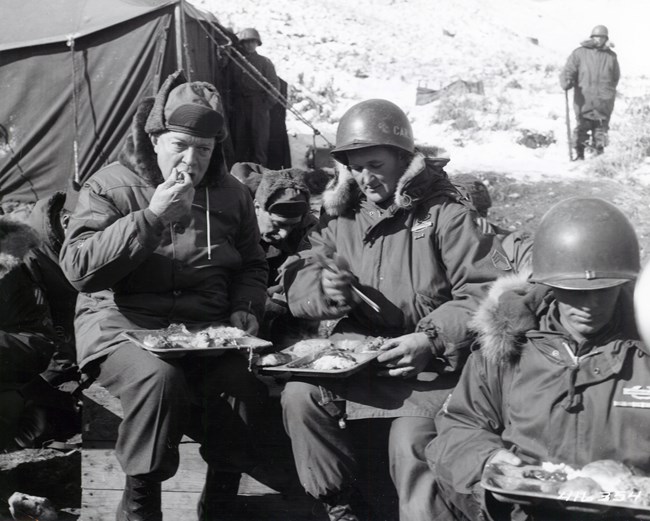

On December 4, 1952, the second day of Ike’s visit, Eisenhower’s travels took him to British troops, a hospital site, several ROK units and divisions, as well as the Second and Third divisions of the U.S. Army. At lunchtime, Eisenhower spent time with the men of the 15th Infantry Regiment, which he had commanded as a lieutenant colonel twelve years prior on the eve of the Second World War. Eisenhower went through the mess line with the enlisted men, gathering pork chops and sauerkraut on his plate. When asked if he wanted to sit indoors with the other officers, Ike responded, “You mean with all that brass in there?” Instead, the president-elect chose to sit in the subzero temperatures with privates and corporals rather than seeking comfort with the officers.

8th Army commander General James Van Fleet had told Eisenhower that the men he was meeting with were pulled off the front line just to spend time with him that day, and that following their luncheon they would soon be returning. Ike’s response was telling of his true priorities, noting, “well, at least I did some good.”

Eisenhower Presidential Library

One of those men who sat and ate with Eisenhower in the Korean cold was Cpl. James Murray, an Oklahoma native. Murray had an eighth-grade education and volunteered for service in Korea in February 1951. By December 1952, he had been wounded three times and was a Bronze Star recipient. Murray was due to come home from Korea at the end of the month after just a few more weeks in harm’s way.

Five days after having lunch with Eisenhower, Murray volunteered to lead a 45-man patrol into no-man’s land on December 9, 1952. According to his commanding officer, Lt. John Richards, the patrol was 1,000 yards short of its objective when they were hit by 55 Chinese soldiers in a heavy ambush. While trying to extricate his men from the danger, Cpl. Murray was hit several times before he was ultimately killed in action.

Lt. Richards said of the slain Cpl. Murray, “He was one of the finest soldiers I've ever known and you can write that in letters of gold.” Richards also noted that in the days between Ike’s visit and Murray’s death, the corporal was beaming with pride at having met the president-elect.

When Murray was killed, Eisenhower was aboard the USS Helena on his way back to the United States, processing what he had seen during his trip to the front in Korea. Upon receiving word that one of his lunch companions had been killed in action, the president-elect issued a statement of heartache:

“I am grieved by the report that Cpl Murray has been killed in action. I have fine memories of our brief friendship. He was a splendid young soldier, typical of thousands of our young men who are fighting in far-away Korea for the principles all Americans cherish and for a just peace. My profound sympathies go to his family.”

While Ike continued to reflect on his visit to Korea, the Murray family could only but reflect on what they had sacrificed for their country. Cpl. James Murry was one of 9 children born to James and Effie Murray. When news of James’s death arrived home, his 8 brothers and sisters all gathered in Porum, Oklahoma, spending Christmas together as a family to mourn their fallen brother alongside their grieving parents. His father, James, told The Daily Oklahoman, of his son’s humility, noting, “he wouldn’t write back anything about his decorations or wounds or actions.” James’s sister-in-law, Mrs. Wilburn Murray, noted the family’s holiday plans that year would still include the fallen soldier. “We’re going to celebrate Christmas just as if James were with us,” Murray was quoted as saying. “We believe he is, somehow.”

Eisenhower Presidential Library

As Eisenhower took the oath of office as the 34th President of the United States on January 20, 1953, he did so raising the same hand that had just weeks before shaken hands with Cpl. James Murray, an American soldier who volunteered to go into harm’s way on behalf of his comrades in arms. Murray’s death was not the only one in Korea, but he was someone who Ike had met. Murray helped to personify the continued cost of waging war on the Korean peninsula, a cost which Eisenhower had to weigh in determining the next steps for the conflict. Ike knew there were hundreds of thousands of other James Murray’s still fighting in Korea, and they were looking to him for a way toward peace.

Eisenhower’s trip to Korea had a profound impact on him. Because of what he had seen, he rejected calls for a renewed offensive, which he feared could escalate the war into a third World War. Instead, he sought a political resolution. In July 1953, an armistice was reached, ending the fighting. This solution had drawbacks, to be clear. The Korean peninsula would be divided once again. Tensions remain there to this day, still threatening to cause larger global conflict. American soldiers, sailors, pilots, and marines still remain in Korea to maintain the armistice. But the fighting had come to a close. South Korea could begin to rebuild.

Over the next eight years, Eisenhower continued to wage peace instead of war, trying whenever possible to save the lives of men like Cpl. James Murray, the 20-year-old from Oklahoma with whom he had once shared a porkchop lunch in the cold winds of a Korean winter.