Last updated: December 16, 2021

Article

A Short Overview of the Reconstruction Era and Ulysses S. Grant's Presidency

Library of Congress

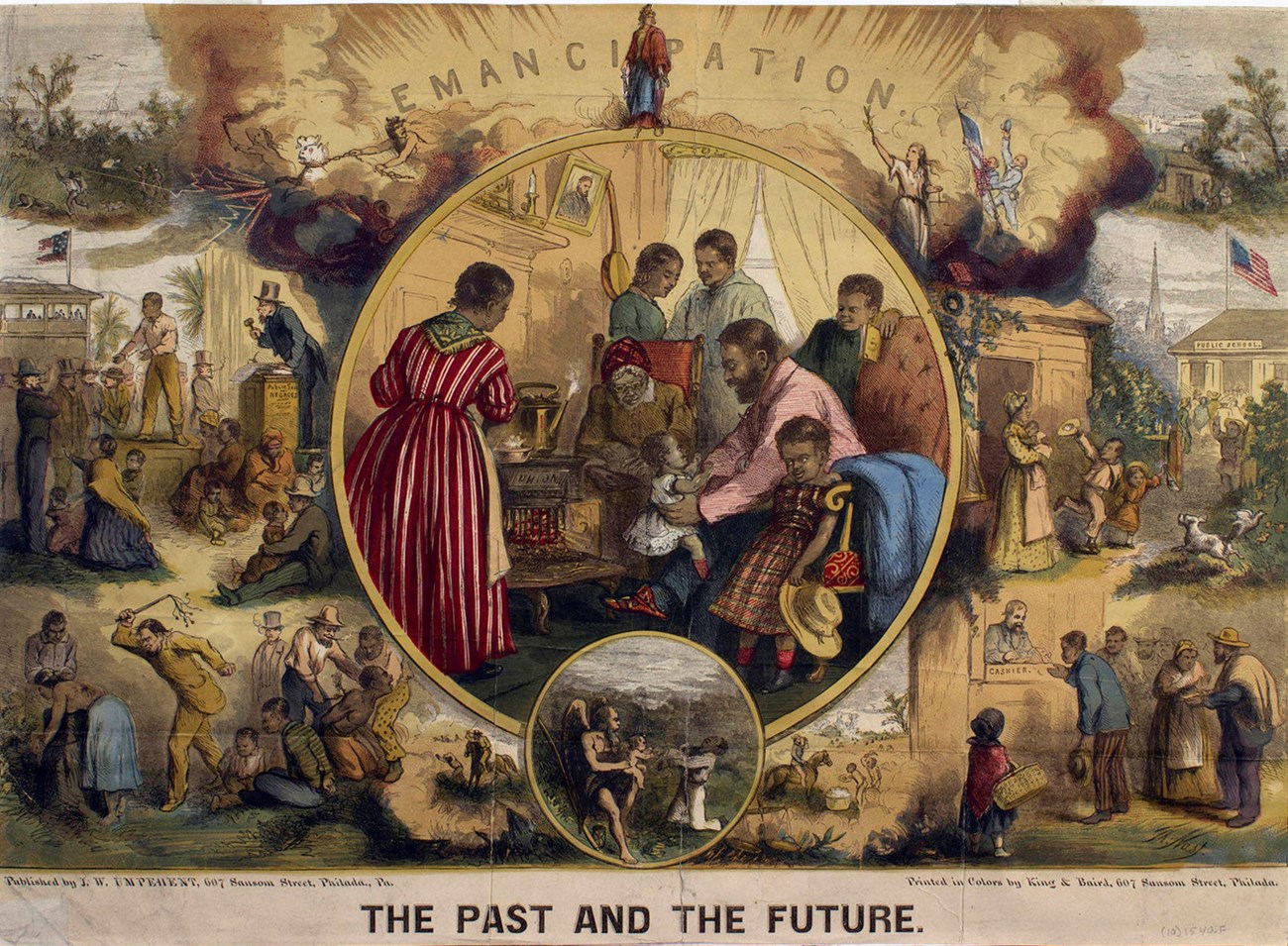

The Reconstruction Era was a transformative period in U.S. history that took place during the Civil War era. Historically, scholars have defined Reconstruction as having lasted from 1865 (the end of the American Civil War) until 1877, when a political compromise between the Republican and Democrat parties allowed for Republican Rutherford B. Hayes to become President of the United States on the condition that the last remaining federal troops in the South be removed. More recent interpretations, however, offer a broader timeline for Reconstruction. Reconstruction Era National Historic Park in Beaufort, South Carolina defines Reconstruction as having started in 1861 (the beginning of the American Civil War) and lasting until the early twentieth century.

The central question of Reconstruction was how to reunite a badly divided country fractured by four years of civil war. Connected to this question were larger discussions about the rights of four million newly-freed African Americans, the extent to which former Confederates should be punished for their role in the war, the fulfillment of "Manifest Destiny" through westward expansion and settlement of Indian Country, and the meanings of freedom and justice in the United States. At the end of the day, what did it mean to be an American, and whose rights were deserving of the full protection of the U.S. government?

Ulysses S. Grant was confronted with these momentous questions upon his election to the presidency in 1868. His campaign theme was "Let Us Have Peace," and he tried his best to promote sectional and racial harmony throughout the country. Prior to his election Congress had already passed, among other legislative acts:

The Civil Rights Act of 1866

Guaranteed protection for all U.S. citizens, regardless of color, to "to make and enforce contracts, to sue, be parties, give evidence, and to the full and equal benefit of all laws and proceedings for the security of persons and property as is enjoyed by white citizens, and shall be subject to like punishment, pains, penalties, taxes, licenses, and exactions of every kind." This legislation overturned "Black Codes" that had been established in the former Confederate states and had been used to keep African Americans in a near-state of slavery.

The Military Reconstruction Act of 1867

Split ten former Confederate states (excluding Tennessee) into five military districts to be overseen by the U.S. military and mandated that each state rewrite its state constitution to allow for black male voting rights before readmittance into the Union.

The 14th Amendment (1868)

Established the concepts of birthright citizenship (anyone born within U.S. boundaries or territories subject to the jurisdiction of U.S. law was automatically a U.S. citizen, excluding Indians) and equal protection of the law.

Grant won the 1868 presidential election by a landslide in the Electoral College, but only won the popular vote by 300,000 ballots. Grant's victory came in large part to nearly 500,000 black voters in the South who overwhelmingly voted for him and the Republican party during the election. Upon taking office, Grant hoped to build upon the previously established framework by championing the 15th Amendment to enhance, protect, and guarantee black male voting rights nationwide. He pushed for the establishment of the Department of Justice in 1870, which was tasked with investigating acts of violence against African Americans. Grant also supported a series of legislative acts in 1871 to enhance the federal government's ability to use the military to stop acts of racial terrorism committed by the Ku Klux Klan, and in 1875 he signed a Civil Rights law that outlawed racial discrimination in public transportation and accommodations, and barred black exclusion from jury service.

President Grant undoubtedly played a important role in what was the country's first civil rights movement in some ways, but Reconstruction had its shortcomings. For the most part, women were unsuccessful in their own fight for voting rights. Many Native American tribes were stripped of their lands, moved onto reservations, forced into an assimilation program not of their choosing, and in some cases massacred by settlers and/or the U.S. Army. The first federal immigration restrictions were passed during this time. And Black Americans continued to face acts of organized intimidation, mob violence, and murder because of their race. The 15th Amendment became an unenforced dead letter by the late nineteenth century.

Reconstruction was successful in helping to reunite a divided country. Equally important, the concept of "civil rights" was established during this period. Grant was nearly universally revered by the time of his death in 1885. A monumental tomb in New York City was constructed in his honor as a result of what was the largest public fundraising campaign in history up to that time. However, what gains were made in the realm of civil rights were under assault by the time Grant died and almost completely destroyed by the turn of the century. In this sense Reconstruction failed not because of President Grant or even because of southern opposition to civil rights, but because an entire nation--North, South, and West--lost the political and moral will to support the cause of equality before the law. The Jim Crow era replaced Reconstruction and ushered in a new era of racial segregation, violence, and murder well into the twentieth century. In parallel, the "Lost Cause" narrative of the Civil War argued that the Confederacy had been justified in its effort to secede from the Union and that Reconstruction had been a mistake. This narrative was promoted by former Confederates, academics, and politicians alike and served to falsely provide an underlying ideology to justify denying equal rights. Although the Lost Cause narrative argued that Grant's presidency had been a complete failure, more recent scholarship has attempted to reevaluate his legacy in a more balanced manner, highlighting both the accomplishments and shortcomings of his eight years in office.

Henry Louis Gates, Jr. Stony the Road: Reconstruction, White Supremacy, and the Rise of Jim Crow (New York: Penguin Press, 2019).

Allen C. Guelzo, Reconstruction: A Concise History (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018).

Heather Cox Richardson, West from Appomattox: The Reconstruction of America After the Civil War (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007).

Brooks Simpson, The Reconstruction Presidents (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1997).