Last updated: April 7, 2025

Article

A River Used to Run Through It: The Borderlands Cultural Landscape of the Onate Crossing in El Paso del Norte

National Center for Preservation Technology and Training

This presentation, transcript, and video are of the Texas Cultural Landscape Symposium, February 23-26, 2020, Waco, TX. Watch a non-audio described version of this presentation on YouTube.

National Park Service

Rachel Feit: My talk is called A River Used to Run Through It. This is the version where a middle-aged Brad Pitt can't fly fish anymore, because he has arthritis. Actually, no. This is actually about the little-known historic cultural landscape of El Paso del Norte and the intense cross cultural exchange that took place on it between 1598 and 1893.

All right, I'm going to set the stage for you. Looking out to cross seemingly limitless highways, strip malls, and dusty scrub land of the US-Mexico border, you may never realize that the 16th century travelers once called El Paso an earthly paradise. Magnificent vineyards, fruit orchards, wheat fields once extended for miles along the fertile Rio Grande flood plain. During the Spanish colonial period and even into the 19th century, the wines from El Paso were revered as the best in the new world. Hard to believe, huh? It's wheat fields supplied grain to thousands along the borderlands. Visitors remarked on the prosperous mills, the gardens overflowing with foliage, tree shaded canals, charming adobe houses that made El Paso del Norte seem like a Levantine oasis.

The story of El Paso del Norte begins with Native Americans, like the Mansos and the Piros who lived in small grass huts along the river. They fished and they hunted. In the marshy bottom lands, it's hard to really imagine what their cultural landscapes may have looked like. Some Spanish chroniclers were frequently very disdainful of Native Americans and other cultures, and the ones that lived along the Rio Grande River were frequently depicted as uncivilized, practically nude savages. Yet these individual groups almost certainly did alter their environment, as we saw in Hueco Tanks, which is just about 20 miles east of this, to suit their needs and archaeological work. Around the area confirms it. In fact, they dug irrigation canals and lived in small pueblos by 80 to 1,200 at least. However, they didn't leave any written records. So, we really don't know exactly how they interacted with their landscape.

For our purposes, we're going to begin this story of this particular cultural landscape in about 1598 when Don Juan de Oñate y Salazar and his wagon train blazed a trail from Northern Mexico up towards New Mexico to the Taos Pueblos. So, for weeks they struggled to cross the salt baked sand dunes of the Mexico desert. Their April arrival at the Rio Grande was an enormous relief. They were dehydrated and weary, and both people and animals in the caravan were so parched that some of them dove headlong into the river and even drowned. The cottonwoods and the willow trees along the river offered much needed shade and allowed them to have blazing bonfires at night. After weeks of privation, Oñate's caravan found plants, fish, birds and game animals to eat and hunt.

Rachel Feit, Acacia Heritage Consulting

Pérez de Villagra, captain and chronicler of Oñate's expedition, compared the river and landscape to Elysian fields full of flowers and buzzing with bees. He described the shady bowers under which they rested and fields of grass from which they're gaunt horses grazed. So, he was very emphatic about his description of the landscape. Although they were grateful to be finally at the Rio Grande, Oñate's party could not initially find a place to cross that could accommodate their heavy wagons and their horses. Their wagons would bog down in the mud and the quicksand. The river was too deep. The current was just too swift. So, after a week of scouting they received some assistance from some friendly Mansos who directed them to a rocky bottom ford several miles upriver.

This hard river bottom located at the entrance to a narrow pass in the mountains was almost certainly well known to the Mansos and the other groups who regularly crossed through the river on their own hunting and trading trips. Not only was it a natural landmark, but logistically it was one of the best places to cross the river that was hemmed in by mountains to the North and muddy, treacherous water to the South and East. Here, Oñate and his men, they don their finest clothes and they perform the customary ceremony of possession, which the Spanish did everywhere, before crossing the river and then heading north up to the Taos Pueblos. This trail marked by Oñate became the Camino Real de Tierra Adentro, a 1,600 mile long road that was used for nearly 300 years to facilitate exploration, settlement, trade, resource development, religious conversions, and military operations in Mexico and the U.S. The Camino Real fostered a cultural exchange that profoundly shaped American and Mexican heritage within the borderlands.

While the trail itself fluctuated according to weather conditions and sociopolitical needs, the Oñate crossing of the Rio Grande river, due in large part to its unique geographic attributes, remained primarily fixed and became known as El Paso del Norte, the pass of the north. So just to clarify here, El Paso del Norte once referred to the pass itself as well as the settlements that sprang up around it. So during the Spanish colonial and Mexican periods, the major settlement was actually on the South side of the river in present day Ciudad Juárez. Although, there were a few farms on the North side of the river as well. These two were considered part of El Paso del Norte.

However, after the Mexican American war, the border between the U.S. and Mexico of course was fixed at the Rio Grande. The American settlement that sprang up on the north side of the river was called Franklin for a time; but when the Mexican city of El Paso del Norte changed its name to Ciudad Juárez in 1888, Franklin became simply El Paso. So, when I talk about El Paso del Norte, I'm really referring to both sides of the river.

Within a few generations of its founding, El Paso del Norte became a crucial outpost in New Spain. Thinking mining settlements, linking mining, agricultural settlements south of the Rio Grande with those on the north. In 1659, Misión Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe was constructed along the road in present day Ciudad Juárez. Here, Fray García de San Francisco y Zúñiga built a church and a settlement to convert the friendly Native Americans who came through this area on their hunting trips and they crossed the river at this location. Under his direction they built an acequia, which was dug near the pass, right at the pass in fact, in order to plant and irrigate crops such as wheat and grapes and fruit trees. With a certain prescience, Zúñiga envisioned mission settlement as one of great importance. So, it became during the Pueblo revolt of the Taos missions in 1680, just a few years later, when hundreds of Spanish and converted Native Americans fled to El Paso.

John Carter Brown Library, Brown University

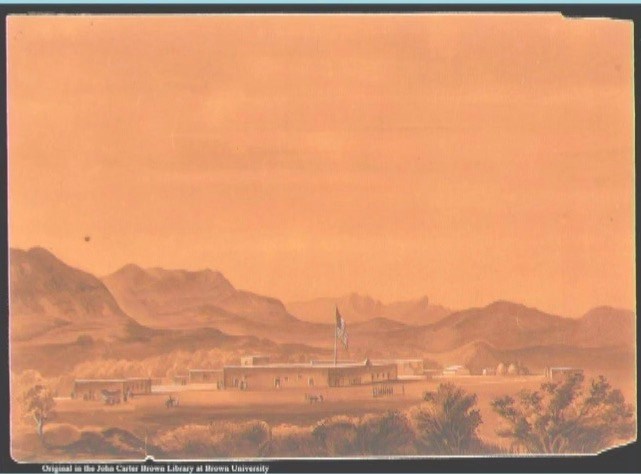

Recognizing then its strategic importance, the Spanish decided to expand the small settlement in 1685 with the establishment of the Presidio de El Paso del Norte near the church, along with a few other missions as well farther South along the river. El Paso del Norte quickly became an administrative center from which the Spanish launched Christianizing efforts, military missions, and carried out commerce. El Paso del Norte was also an important agricultural center. Most of the accounts from both Spanish and English sources talk in great deal about the orchards, the wheat fields, and most importantly the vineyards that stretched along the river for miles.

Pedro de Rivera wrote that the wines from El Paso del Norte were superior to the best wines anywhere in New Spain. A century later, James O. Pattie, an American, wrote something similar when he said, "I know not whether to call Paso del Norte a settlement or a town. It is in fact a kind of continued village. Fronting this large group of houses is a nursery of the fruit trees of almost all countries and climes. It has a length of eight miles and a breadth of nearly three. I was struck with the magnificent vineyards of this place from which are made great quantities of delicious wine."

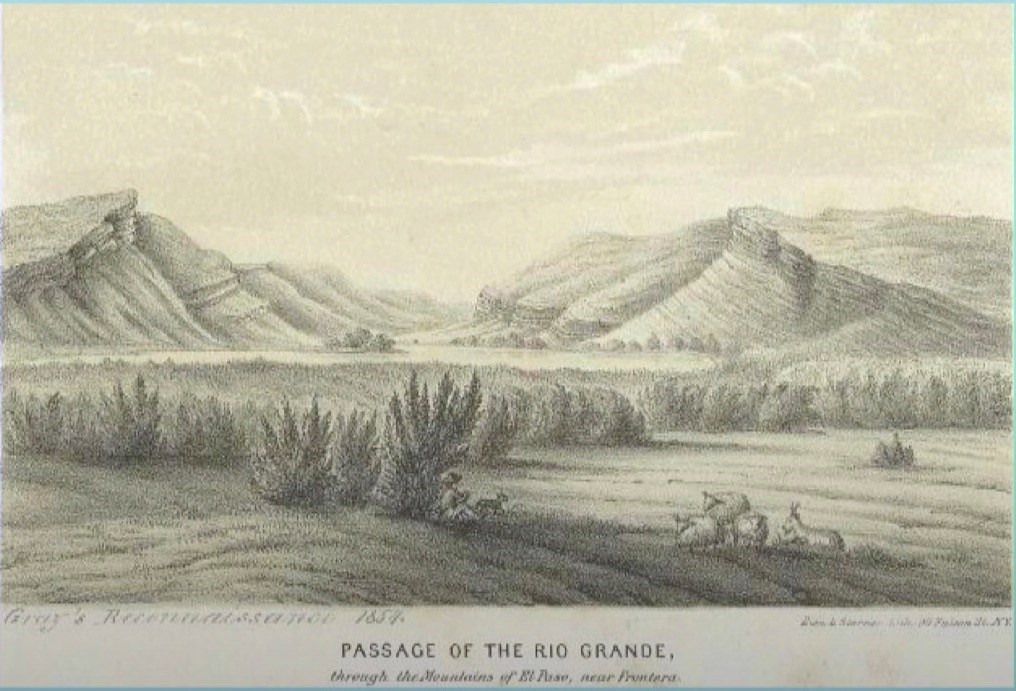

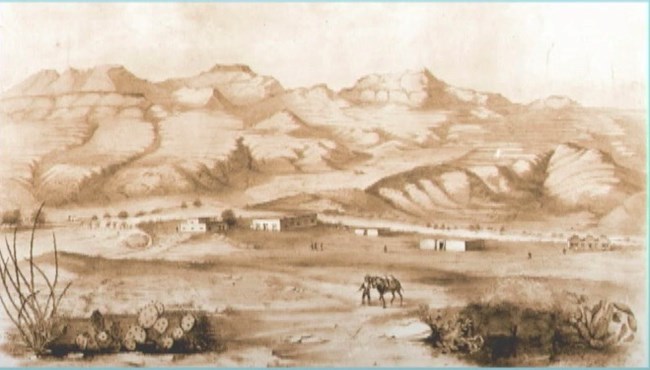

When Zebulon Pike came through El Paso del Norte in 1807, that was a few years earlier, he followed the Camino Real from New Mexico and crossed the Rio Grande at a bridge that the Spanish had built at the head of the acequia, right at the Oñate Crossing. By the mid-19th century he described those same vineyards. By the mid-19th century, wheat fields and fruit orchards gave both sides of the river a romantic aura. You kind of get the idea from these pictures here, from these paintings.

Upon first reaching present day El Paso, Anson Mills remarked that the town consisted of, "Some 150 acres in cultivation, in beautiful grape, apple, apricot, pear, peach orchards, watermelon, grain, wheat, and corn. It seemed more beautiful, especially when under the shade of the large cottonwood trees along the acequias." So, a picture is starting to emerge here. El Paso was a very virgin place at one time. In describing El Paso del Norte in 1884, another visitor wrote it's gardens and vineyards in its slow running acequias meandering through narrow streets and adobe walls gave to El Paso del Norte an aspect different from other frontier towns, as if a fragment of Southern Mexico had been transported here across the intervening deserts. Photographs and paintings from the late 19th century, like these, offer glimpses of the former vegetation of the Oñate Crossing landscape. We've got cottonwoods and willow trees fronting the river banks, and they grew quite tall.

Meanwhile, the orchards and vineyards and wheat fields stretched down the hillsides and along the riverbanks for miles. I don't have any pictures of the vineyards, and I wish I did. I can't find a single one, which maybe they weren't as large as everybody said they were. Anyway, in the early 19th century the cultivated wheat that was grown in El Paso was milled by a man named José María Ponce de León, who received a Mexican land grant in 1826. Although he may have been there much earlier and opened a mill on the north side of the Rio Grande, and what would today be downtown El Paso. However, that mill washed away in one of the cataclysmic floods that frequently changed the course of the river.

Rachel Feit, Acacia Heritage Consulting

He rebuilt on a higher ground, but that mill was also damaged from flooding. So, by the 1840s there was a need for another mill. Simeon Hart was a former cavalryman who'd fought in the Mexican American war. Along the border, he was wounded in northern Mexico. While convalescing, he fell in love and married the daughter of a rich mill owner in Santa Rosales. After the war, he stayed on the border. In partnership with his father-in-law, he built a home and opened a mill business at the river ford of the Camino Real. It was strategically placed along the road. The mill was powered by water diverted from a Spanish dam on the Rio Grande. Let's see, they got special permission to divert the water from the dam. Hart's Mill immediately began supplying flour to American military outposts, remember, he's former military, that were established along the newly drawn U.S. and Mexico border, and then in New Mexico territory. Hart's molino became a center for trade, transportation and hospitality in El Paso for years to come. Hart himself eventually purchased a stage line and operated his own freight hauling company, both of which used the Camino Real to transport goods back and forth from New Mexico territory and into Mexico.

Therefore when the U.S. fought to reestablish a permanent defensive post on the border in 1878, they'd already tried and failed several times in other places in El Paso. What would become Fort Bliss, Hart's Mill area seemed like a natural choice to them. The property was already well known to the military, having supplied it with flour for 25 years. It was strategically placed along the border on the main road, on the crossing into Mexico near the customs house, near international boundary marker number one, which had just been placed there and could easily be supplied with products from both El Paso del Norte and the fledgling town of Franklin and then other places in northern America. It was also on the planned Southern Transcontinental Railroad route, which had been in the planning stages for years and finally came through the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe, finally cut through the parade ground. In fact, it cut through the parade ground of Fort Bliss in 1881. The Southern Pacific was not far behind it.

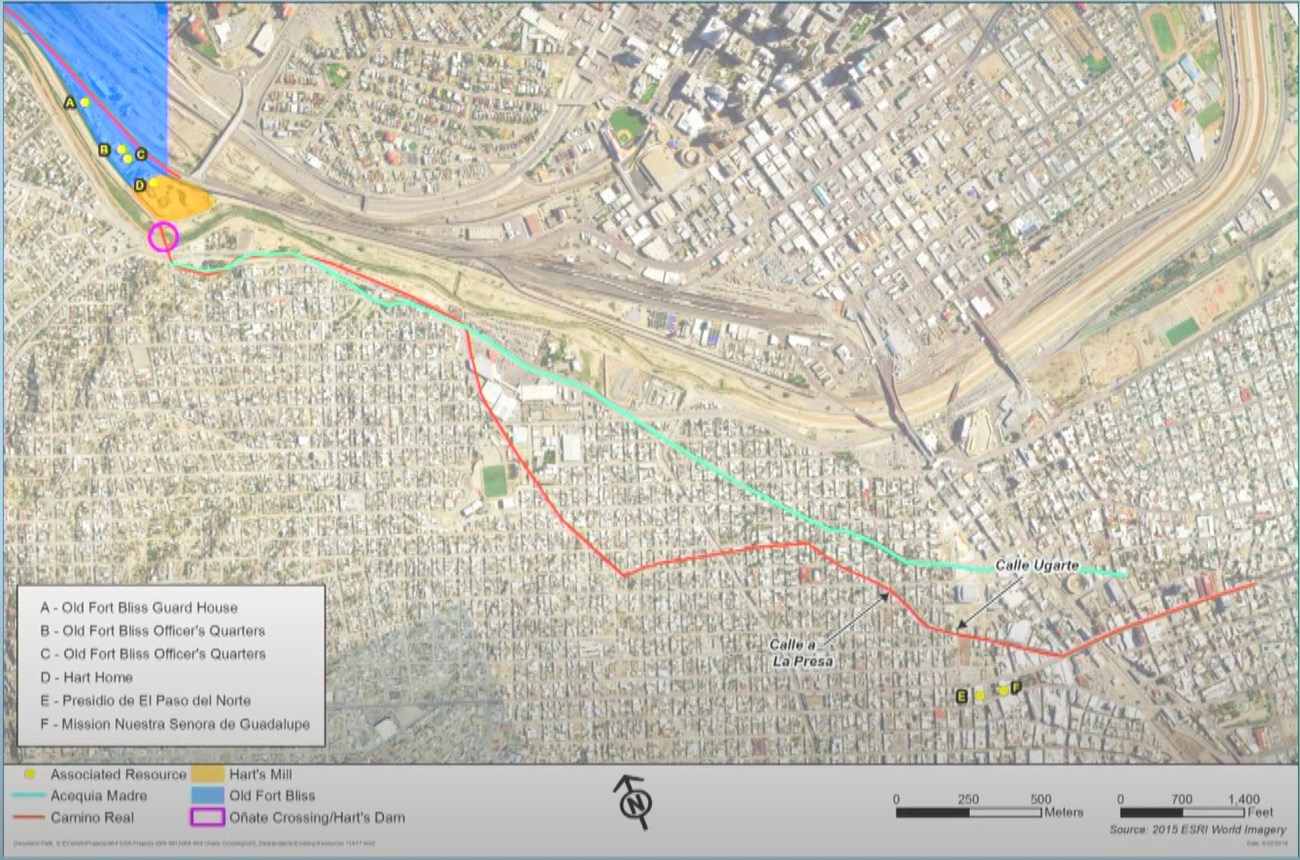

This wasn't ideal from a spacial perspective. The railroad did connect this remotely located military post to national markets and communications. Fort Bliss at Hart's Mill was then occupied until about 1893 when it literally ran out of room to expand. At that time, it moved to its current location, Lanoria Mesa on the East side of the Franklin mountains. That move, along with the 1895 closure of Hart's Mill, represents the end of strategic significance for the Oñate Crossing at El Paso del Norte.

So as Fort Bliss is moved, the expansion of the railways and the rise of other industries, the focus of economic activity in El Paso shifted away from the Oñate Crossing and the Camino Real toward what's now considered more downtown El Paso. Hart's Mill closed in 1895 and was left to ruin. During the 20th century, the Camino Real in Texas became Smelter Road. It was then paved in the 1930s to become Donovan Drive. Finally, between 1951 and 1954, it became part of main street viaduct and its name was changed to Pisano Drive. So, it's still there, the Camino Real.

Rachel Feit, Acacia Heritage Consulting

The buildings from old Fort Bliss, although some were reused in later times, slowly succumbed to age and new industries. This flat map from 1893 of Fort Bliss, only the stuff in red is stuff that's still left. Meanwhile, water control efforts of IBWC really radically transformed the river corridor starting in 1934. As El Paso, the American town of El Paso, and Ciudad Juárez have grown, the once picturesque agricultural landscape described by 18th-19th century travelers has been slowly transformed into a modern urban center. These comparison aerial photos show how things have changed, particularly on the south side of the border. Today, the famed vineyards and the orchards are long forgotten. The mighty river and its offshoot canals are little more than concrete gullies filled with shallow, sluggish water. More importantly, the free flowing movement of people, goods and culture across the river is hindered by checkpoints, border walls and military posts. Here's a comparative view. These three images are all kind of taken from the same point of view. This bottom one is from a Google Earth street view, from like 2017. You can't actually stand there, because it's a highway now.

In 2017 the National Park Service hired AmaTerra Environmental, contracted to find the cultural landscape history of the Oñate Crossing and inventory its remaining cultural resources and offer them a preliminary assessment of them. This would eventually become the basis for a complete cultural landscape report and multiple property National Register nomination. So, the latter study is now being undertaken with support from El Paso County and PaleoWest as its consultant, and I'm sub-consulting with PaleoWest for that effort. I managed the 2017 study for AmaTerra.

What we found in 2017 was that in spite of the radical changes to the landscape, some resources do remain. Specifically, the resources that today make up the Oñate Crossing cultural landscape in this study are loosely connected. The existing resources include the trail itself. These are some comparative images, then and now images, comparative images of each of these resources The Misión de Guadalupe in Ciudad Juárez, the Spanish Presidio of El Paso del Norte, the Acequia Madre and Ciudad Juárez, the hard home, two officer's quarters from Old Fort Bliss and a guard house. Their age and function differ pretty widely. What unifies all of these seemingly disparate resources is the Camino Real de Tierra Adentro, which was the most important transportation route in the borderlands region for 300 years.

The Oñate Crossing of El Paso del Norte is now considered its own cultural landscape along the Camino Real de Tierra Adentro, which is also an NPS designated cultural landscape. That's kind of the defining limits of it, here, or what we defined as the limits of it, although it was very difficult. One of the defining aspects of this particular border locale is its deep rooted transnational connectedness. It's best exemplified in the name, El Paso del Norte, which at various times has referred to the border crossing itself, as well as the communities on either side of the river. The constantly shifting course of the river itself created a permeable boundary. Even after 1848, the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo defined the geographic and political border between the United States and Mexico as the deepest portion of the Rio Grande.

Just as the built environment resources serve communities on both sides of the river, the people who inhabited the border moved back and forth across it with considerable fluidity. Mill owner Simeon Hart married the daughter of a prominent business owner on the Mexico side of the border. Hart's own business relied on wheat grown on both banks of the river. Up to the 1920s, the people who lived in this area saw little distinction between Mexican and American. In social circles on both sides of the river, there's a quote, "The fact that one man was a Mexican and the other an American was seldom mentioned, and I believe seldom thought about. Each man was esteemed at his own real worth." That quote is from Mill's. Condescension aside, the commentary of more than one American writer makes it clear that businesses, social life, and institutions frequently relied on cross border influence and reciprocity in the El Paso area.

Rachel Feit, Acacia Heritage Consulting

Transnational interactions continued all the way up to the 20th century. Simeon Hart's son, Juan, was a prominent business member of the El Paso and social community. He frequently lodged in Ciudad Juárez when not at his home in Hart's Mill. A smelter then opened just North of Hart's Mill in 1887 to process ores that were coming in from both sides of the border. Even the Mexican revolution that took place between 1910 and 1917 was very much a trans-border affair in which the American city of El Paso served as a staging area for revolutionaries, refugees, and reporters alike. It's no accident that the Mexican revolutionary, Francisco Madero's provisional government headquarters was located at the Casa de Adobe right across from smelter town, just up the road from Hart's Mill and the Oñate Crossing. It was a key point from which to obtain supplies and munitions from American sympathizers and to cross the river and escape Porfirio Diaz's federalist army. In fact, this picture shows Americans literally watched the Mexican revolution taking place from across the border. I love this picture.

The central problem for the Oñate Crossing at El Paso del Norte, this particular cultural landscape becomes … and this is for the future now, how best to commemorate it and interpret it. Although bits and pieces are still there, we've got these pieces that are radically diminished by the lack of flow and connectivity. A unifying theme for this culture, which is the unifying theme for this cultural landscape. Current border politics make it almost impossible to interpret the resources on either side of the river in tandem and to connect them back as they should be. In the case of the Hart's Mill area, they're also undermined by neglect and deterioration. Although, I should mention that actually some of the resources have recently been … there's a developer that's planning to turn some of the officer's quarters at Old Fort Bliss into a boutique hotel, which is actually seen as a good thing among many people in El Paso.

The lack of archeological investigations around these resources in both Ciudad Juárez and El Paso is another problem for interpretation. Missing resources associated with the Oñate Crossing or Camino Real are many and include portions of the trail itself and the old dams over the river, the northern most portion of the Acequia Madre, Hart's Mill, half the Hart home and numerous buildings from Old Fort Bliss. So given the number of missing resources associated with the Oñate Crossing landscape, due to 20th century development, it's reasonable to confer that archeology could greatly enhance interpretation of the resources on both sides of the border. Hart's Mill, in fact, was already a ruin … let's see … in 1936 when this HABS photograph was taken. Today, nothing remains but a parking lot and some markers. A few archeological investigations have occurred in conjunction with road and IBWC maintenance projects. These have uncovered archeological remains, such as debris dumps and even the old hospital building from Old Fort Bliss; but further research and more importantly targeted research has never been undertaken for any of these.

No archeological work is known to have been conducted in Ciudad Juárez at any of the associated resources there. However, given the changes over time and the configuration of the ancillary buildings of the Misión de Guadalupe, it's likely that archeological remains could be present in the courtyard or anywhere around the church. Likewise for the Presidio de El Paso del Norte, which was extensively remodeled in 1943 and even earlier than that for road improvements. In fact, I came across a newspaper article from 1901 that talks about Spanish guns being unearthed while demolishing a portion of the old jail for an extension of the Avenida 16 de Septiembre, which is where a portion of the Camino Real runs in Ciudad Juárez. There's a quote from it that says, "The find consisted of seven muskets of antiquated pattern. Two heavy guns, such as were known as aquebueses, so heavy that a man could not even support them in ancient days. Portions of two cannons were also unearthed." The article goes on to say that the guns were found under the floor of an abandoned wing of the old Presidio building. So there's probably some remains there, but nobody really has done any sort of targeted studies.

Fast forward 120 years, that landscape has now become even more imperiled. Particularly on the American side of the border, but on the Mexico side as well, where urbanization and development continue to threaten what remains of the Oñate Crossing. The research for this cultural landscape being undertaken today is really documenting the last vestiges of a period in borderlands history that reflect a time of incredible cultural exchange, identity formation and nation building and even conflict. It highlights the partnerships that were once fostered by nations north and south of the border to promote settlement agriculture and trade along the frontier. Unfortunately, against a backdrop of anti-immigration rhetoric and policy, the last vestiges of this historic landscape of El Paso del Norte and the Oñate Crossing is a poignant reminder of what we lose when we put up walls. With that, I'm just going to say that the real challenge, the next stage of this project, is really to put together a complete cultural landscape report and then define treatment recommendations and interpretive plans. This is going to be incredibly challenging given what's left of the resources and what's left of the landscape, though at least at this point we know quite a bit about it. So, there's some things we could do.

Thank you very much.

National Park Service

Speaker Biography

Rachel Feit is an archaeologist, cultural historian and the owner of Acacia Heritage Consulting. She has worked for more than 20 years in cultural resources management consulting and specializes in historical archeology, archeological and historical context development, and heritage planning. She has a B.A. in Anthropology from the University of Chicago and a M.A. from the University of Texas at Austin.