Last updated: July 4, 2024

Article

A Revolutionary Inheritance

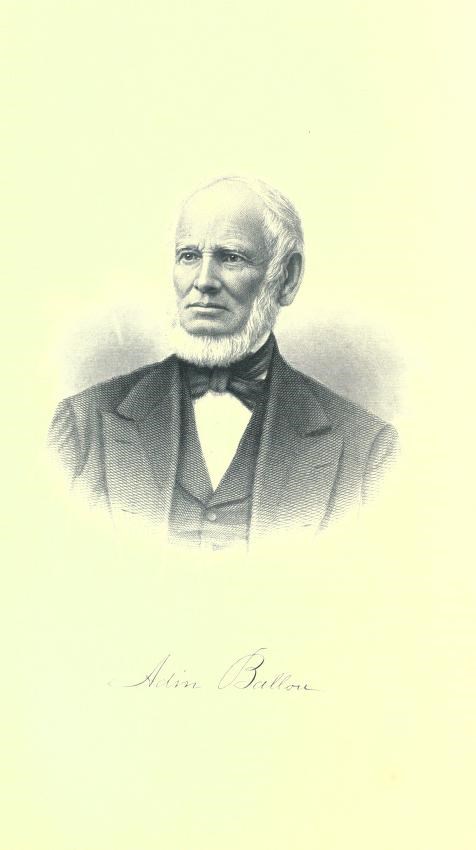

The Reverend Adin Ballou (1803-1890) was known as a “man of peace.”

Raised in the first generation to inherit the American Revolution, Ballou wrestled with big questions of faith throughout his lifetime. Growing up with the rise of American industry, Ballou chose not to pursue wealth or financial gain. Instead, he ministered to thousands of people across the Blackstone Valley, building a following as a controversial but impassioned minister.

By the 1830s, Ballou’s faith and convictions became so strong that he felt he must act beyond the pulpit. Eventually, he led a group of people to create their own Dale of Hope in Mendon, Massachusetts. The community of Hopedale, established in March 1842, would become a prosperous commune, and then, a company town in the mid-to-late 19th century.

Ballou espoused a number of polarizing religious and social beliefs. He advocated for the equality of women and the abolition of slavery. Ballou was troubled by the idea of war and promoted non-violence in the form of Christian non-resistance. Among leading philosophers of pacifism, Ballou remains an important thinker.

At the end of his life, a common adjective used to describe Ballou was “peaceful.” Yet coming to non-resistance was in fact a major struggle for Ballou, and one that would be challenged throughout his lifetime. A frequent and voluminous writer, Ballou left a long paper trail behind about his life’s journey, Hopedale, and his family’s ancestry. The son of a Revolutionary War veteran, Ballou provides an ideal subject to consider how a person raised in the early years of the country’s history grappled with big questions about war and peace.

Adin Ballou came up in a place seemingly filled with Ballous—Cumberland, Rhode Island. Adin was the 7th of eight children born to Ariel Ballou (1758-1839). From Ariel’s first marriage to Lucina Comstock (1782), Ballou had the following (half) siblings: Rosina, Abigail, Cyrus, Arnold, Sally, and finally Alfred, who was born in 1799. That marriage lasted nearly two decades, but Lucina sadly passed away in 1801. After Lucina’s passing, Ariel married Elida (also spelled as Edilda) Tower in June of 1802. Their son Adin was born in April 1803, and one more child would follow, a brother named Ariel, after his father.

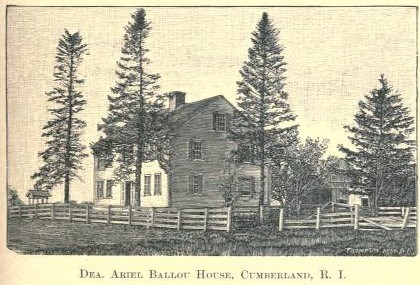

Ariel Ballou Sr. had a farm, sawmill, and cider mill. He was also an investor in woolen mills. He had a comfortably sized home, even with so many children. Adin described his father as “an intelligent, upright, enterprising farmer” who “possessed himself, by inheritance and subsequent purchase of over two hundred acres,” in Cumberland and nearby Wrentham, MA.

Father Ariel purportedly “took good care that none of his family should eat the bread of idleness, form dissolute habits, or grow up incompetent to bear their share of life's responsibilities.” Long before Adin’s arrival, Ariel had taken on his share of responsibility by serving as a Captain during the Revolutionary War. Adin wrote that his father spent part of his “early manhood…as a soldier of the Revolution and met the enemy a few times on the battle field [.]”

Adin Ballou’s father was not a career solider; eventually, he settled into a ministry, and raised his family. Adin summarizes this change as one from bearing “the title of militia Captain” to “that of Deacon [.]” Adin only partially followed in his father’s footsteps. Too young to serve in the War of 1812, Adin instead went straight to ministry. He spent time in the early 1820s finding his way, trying to get a foothold somewhere, moving between RI, MA, and even NY for a short period. By February 1824, Adin had returned to the Blackstone Valley, moving between Bellingham, Milford, and Cumberland to minister to others.

In the 1830s, while Captain Ballou was working out the details of his war pension, Adin was struggling with his position on peace. After considerable debate, and personal turmoil, Ballou made a decision in the late 1830s. He would abide by “the principles of Christ's gospel in the spirit of holy martyrdom.” Living “in awe of its sublime wisdom and goodness” Ballou then “yielded to my highest convictions. I became a Christian Non resistant.”

Ballou’s beliefs put him out of step with many of his “countrymen” living in the United States. His principles were “not in accord with the popular Christianity of Christendom, but I am confident that it is in accord with the Christianity of the New Testament.”

Reflecting on this time in his life, Ballou argued: “If this made me a fanatic in 1839, I am a still greater one in 1889 though doubtless a wiser one by disciplinary experience.”

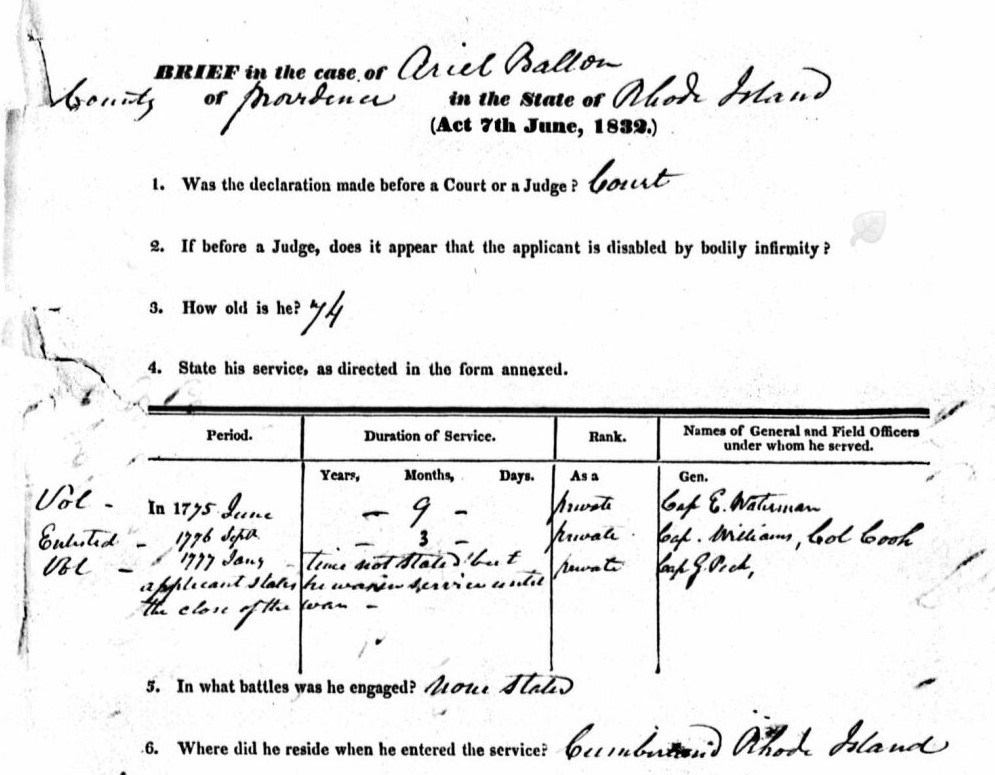

When Adin chose to summarize his father’s service to the country, he recalled that Ariel “used to say he hoped he killed no one---though he knew not the effect of his bullets.” This may have also just been Adin’s selective way to remember his father’s soldiering. A more extensive record of Ariel’s service record can be found in his attempt to get a pension in the early 1830s. At the age of 74, perhaps out of financial need, Ariel Ballou decided he was owed something for the years he spent apart from his family fighting a war for independence.

According to his own testimony, and that of other servicemen, Ariel first became a solider “in June 1775 [when] he joined a company of minute men for one year as a private commanded by Capt. Elisha Waterman…” Ballou was ordered to march “to Newport first, where we were stationed & then at Bristol to their places there on duty for nine months [.]” Ballou continued his service in September 1776 as a private in the Rhode Island State Troops led by Captain Williams and Isaac Cook’s Regiment. They “were stationed on Rhode Island & were there when the British took possession in December 1776.”

Ballou once again a minuteman in January 1777 under Captain George Pick’s company. For this service, Ballou and his fellow soldiers were “under immediate orders of the Governor” – Ballou “belonged to this company until the end of the war & always went with the company when called into service [.]” Ballou spent considerable time on Aquidneck Island and was active in Newport during key points in the war, including Spencer’s Expedition (October 1777) and Sullivan’s Expedition (August 1778). He testified that he “was in the Battle on the 28th of that month [August 1778] all day long” – two days before troops would leave the island, defeated by the British. In June 1832, Ballou was awarded $200 in backpay as well as a $40 semi-annual allowance set to end in 1836.

NPS Horrocks

Ariel Ballou died in 1839, just a few years after getting his pension. He is buried with family in Cumberland, in the Elder Ballou Meeting House cemetery. He is remembered as a Deacon. Nearby, Adin’s maternal grandfather, Levi Tower, also lays in eternal rest. A Captain of a Rhode Island Company, his grave carries the honors of a solider, and American flags are refreshed seasonally next to his plot. In 1892, one of his descendants applied for membership with The Rhode Island Sons of the American Revolution. This descendent explained, “Capt. Tower served his county well and lived to a good age.”

All family units have myths and stories about their collective past. In the case of the Ballous, much of what is known now about the family comes back to ink spilled by Adin. As the self-appointed family historian and genealogist, Ballou wrote An Elaborate History and Genealogy of the Ballous in America. Elaborate is an apt word for his big volume, where Ballou includes birth and death dates and how he prefers to memorialize family members. Ballou knew his roots well. He was descended from a fighter, and from Maturin Ballou (1615-1662), one of the earliest men who settled in Providence, RI. Maturin was a “co-proprietor” of the colony and one of the “kindred adventurers” who settled with Roger Williams. Baptist Ballous spread out from Providence to other parts of the colony, including Cumberland, where Adin was raised.

In many ways, Adin Ballou clearly saw his father as a pattern for himself. By middle age, Adin would, like his father, have considerable land holdings, agricultural projects, and a life in the ministry. Yet Adin also came of age at a time when what was considered possible – economically, politically, philosophically – was quite different from the world his father was raised in. Ariel spent three formative years engaging in a battle for independence. Adin took a different route, choosing to separate and pull away from the society that his father and grandfather fought to establish.

Adin Ballou had many radical beliefs, but his dedication to non-resistance was one that tested even some of his fiercest allies when the Civil War came. In Hopedale, Ballou had gathered allies who pledged a life of loving one’s enemies. In a History of Hopedale co-authored with his son-in-law, Ballou included the pledge laid out for members, and their founding beliefs. The people who came to Hopedale endeavored to see that “The kingdom of God's righteousness and peace is to be developed on earth as never before.”

Two months after Ballou’s passing, the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) was established by a group of leading women in the nation’s capital, in October 1890. The descendants of Capt. Ariel Ballou have not made claim on their ancestor’s war lineage. Instead, there is a statue in Hopedale dedicated to their ancestor named Adin, a man who believed in the power of peace.