Last updated: January 23, 2021

Article

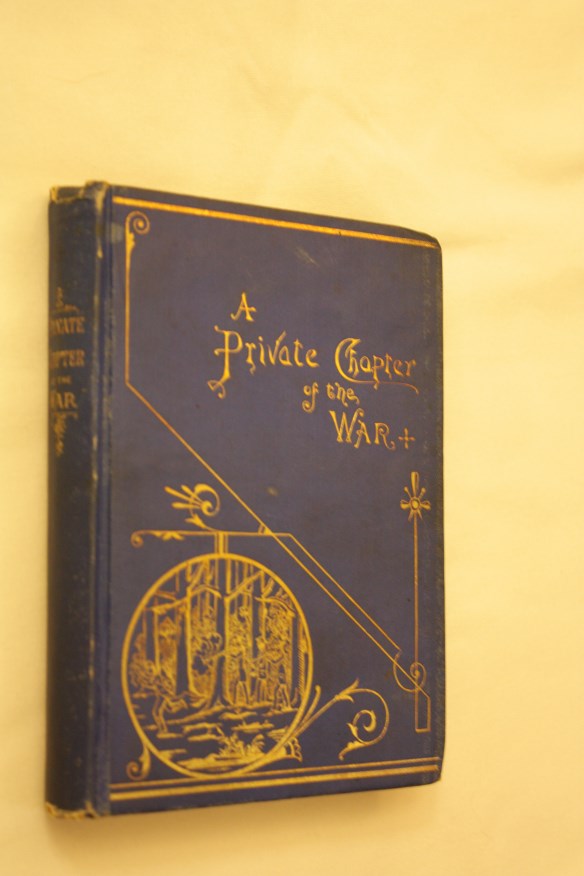

A Private Chapter of the War, Part II

Library of Congress

Wikipedia

September 10. …Confederate cavalrymen and stragglers on foot are wandering about from plantation to plantation, purchasing pigs, corn, chickens, potatoes, etc. They report that the ‘whole army is encamped at Jonesboro’ (on the railroad, only twelve miles eastward). “The Atlanta army fallen back!” The writer immediately determined that Smith’s was no place for him. He yearned for the other flank—the right flank of the Federals—as the rebels were manifestly being pressed eastward. At all events, he discovered that he was now among the enemy, and either flank would be preferable to the center… There’s no delusion this time—Sherman’s in Atlanta! Our cavalry raiders will certainly “hang about” the rebel flanks…

While attempting to flank the Confederate forces, Bailey and his guide, Jim, encounter a runaway slave couple. The man has a carbine that he took from the body of a Union soldier who drowned attempting to ford a river. Bailey convinces him that he would be in more danger if he is found with the gun, and as Union property, it would be wise for the slave to turn the gun over to him. For the first time since his capture on July 22, Lieutenant Bailey is now armed. On September 11, he was at the Freeman farm once again. Jim was sent to gather intelligence.

October 7. Bailey finally leaves the Freeman farm, along with Jim, with the goal of reaching Lithonia, and the North Georgia Railroad. They are told the Federal forces are at Decatur, but that there are Texas Rangers roaming through the area searching for deserters and runaway slaves. After midnight Bailey and Jim reached the railroad just west of Lithonia, fifteen miles from Decatur. “No halting, no resting, no lagging; we are between the lines of two armies, and daylight will find us at Decatur, or worse.”

Daylight did find them in the Union fortifications a quarter mile east of Decatur. They “are vacated—campfires still smoking, but the Federals gone. Smiling Hope had beckoned us on, only to make despair the more certain. The coveted Federal lines at last, and nothing to greet us but the refuse of a camp and smoldering remnants of campfires with which were kindled by friends! Despondent—hungry—footsore—cheated—exhausted—chafed—irritated—lacerated—drooping in the gloom of faded hopes.”

CivilWar.org

During the day Bailey and Jim are overtaken by a pair of armed deserters, one in butternut, the other dressed in blue. Bailey is again a captive, and disarmed; his captors make it clear that they have no intention of treating him as a prisoner of war. Late in the afternoon one of them says, “My friend, this is as good a place to die as any man could wish.” Given an opportunity to pray before dying, Bailey decides that “it’s manifestly too late to pray ‘deliver us from evil;’ God helps those who help themselves.” Bailey runs. Three shots were fired at him in rapid succession, and a fourth later. The second shot threw Bailey to the ground, entering his right shoulder, passing through his shoulder blade and penetrating his lung. But he got up and ran on. After the captors had fired all their loaded weapons, Jim ran as well, soon catching up with Bailey. The two of them staggered through the woods until sunset. Bailey sees the light of a farmhouse and tells Jim, “I believe I am mortally wounded. But if I’m mistaken, Jim, that light—that house—whatever it is—is my last chance for life. I know I can’t live in the woods through this night. I know it. Take me to that house.”

The house belonged to a widow named Carrie E. Hambrick, who, with her sister, took Bailey in and nursed him overnight. Jim, meanwhile, was sent to find the Federal forces. By mid-day, October 9, a force of about 150 Federal troops, with an ambulance and surgeon arrived. “Ah! Lieutenant, we’ve come for you!” Almost immediately the room was filled with officers and soldiers…faithful Jim in the midst of them.

Our little column passed through Decatur, and another little jaunt of six miles brought us to Atlanta. Atlanta! That “Hood had made up his mind to hold at all hazards.” Atlanta! That “the Yankees can never take, sir.” Atlanta! before whose gates the rescued soldier, while concealed in distant Southern forests, had so often heard the thunder of Federal cannon. Atlanta! At peace beneath the flag of the stripes and stars. As we neared the fortifications, the escorted ambulance passed the battlefield of July 22nd, and over the very road beside which its wounded occupant was captured, which spot was immediately identified with much interest; but the grand feast to his bedimmed vision was the sight of the old flag. How majestically it floated where before he had seen only “stars and bars.” Never before did the flag of the Union appear so bright and glorious; never was he prouder of the uniform he wore; never so desirous of witnessing a vigorous prosecution of the war for the Union; never before so appreciative—so delighted—so comfortable—so safe—so satisfied under the glorious old stars and stripes.

NPS photo

A month later George Bailey was at home in St. Louis. Fifteen years later he wrote his “Private Chapter,” to which he added this coda:

The writer respectfully submits that, from the facts within his limited experiences as herein related, the following conclusions may readily be reached:

I. That the whole South was not in sympathy with the war against the Union; that there was much in the Southern maxim, “The rich man’s war, and the poor man’s fight;” and that in numberless instances the poor were the mere victims of circumstances which placed them under the control of the aristocracy of wealth, and that while necessity forced action, very many of the actors bore no real enmity against the government; that with them it was not a matter of choice, but they were mere floaters on the tide of public sentiment, which their standing on the social scale permitted them neither to control nor to stem.

- That the negroes at the South, as a class, were opposed to the enemies and true to the friends of our government, and were ever ready and willing to render aid and comfort and to make cheerful sacrifices, by day or by night, for our unfortunate straggling “boys in blue,” to whose interests and welfare they generally evinced a remarkable degree of fidelity.

III. That localities should not always be condemned because of the unlawful acts of a few; for the vicinity that produces outlaws and fiends to wound, may also be capable of furnishing angels to save and comfort the wounded.

- That nobility of soul cannot be bound within the narrow confines of sectional prejudices, but, when opportunity is presented, is capable of asserting itself in spite of bitter enmities naturally engendered by civil war.

- That among the real enemies of the government there were at least a few whose prowling proclivities found “duties” at the rear, as a pretext to avoid the dangers which threaten soldiers at the front—beast of prey in human form, whose cowardly instincts compelled them to seek only safe opportunities to vent their spleen against the government by adding the crime of murder to that of treason.

Tellingly, Bailey’s memoir is dedicated “To Mrs. Carrie E. Hambrick of Atlanta, Ga., whose nobility of soul manifested itself in rising above surrounding prejudices and circumstances, proving superior to them, by extending welcome and bestowing aid and comfort upon a helpless stranger whom the misfortunes of war brought to her door, and whose life was preserved by her motherly care, sympathy, and encouragement,…”

But why did George Bailey send a copy of his book to General Garfield, then the Republican candidate for President of the United States? Was it simply “veteranizing” (a usage coined by Sherwood Anderson)—one old soldier to another? Or did Bailey hope that the conclusions he reached, based on his experience of the war, would be meaningful in the political context of the presidential campaign. We do not know if he sent a copy to Winfield Scott Hancock, the Democratic nominee, and another Union veteran. Nor do we know if Garfield read his book.

What we can say with some confidence is that Bailey’s “Private Chapter of the War” taught him things that he felt were unique and worth sharing fifteen years after the event. Even if George Bailey’s conclusions did not add to the political conversation of 1880, they were important then and they remain relevant today. We are glad they are here, preserved in the library of our twentieth president.

Written by Joan Kapsch, Park Guide, James A. Garfield National Historic Site, May 2016 for the Garfield Observer.