Last updated: January 23, 2021

Article

A Private Chapter of the War, Part I

NPS

When Johnny comes marching home again

Hurrah! Hurrah!

We’ll give him a hearty welcome then

Hurrah! Hurrah!

The men will cheer and the boys will shout

The ladies they will all turn out

And we’ll all feel gay

When Johnny comes marching home.

Get ready for the Jubilee,

Hurrah! Hurrah!

We’ll give the hero three times three,

Hurrah! Hurrah!

The laurel wreath is ready now

To place upon his loyal brow

And we’ll all feel gay

When Johnny comes marching home.

Written and published in 1863, this optimistic song lifted the spirits of Americans north and south during the final, difficult years of the Civil War. Those at home may have expected Johnny to return older, perhaps a bit battle-worn, but essentially unchanged from the enthusiastic patriot or the reluctant conscript they had sent off to war.

But the men were changed, each in his own way, based on his own experience; all in ways that they could not readily share as they tried to readjust to civilian life. Each had his own “private chapter in the war;” but most, according to a Wisconsin officer “thought only of how [they] could best take up the pursuits of peaceful industry.” They “had then no inclination to study the comparative analysis of the war, or the proper bearing it had upon our country and race.” As much as the country was in need of reconstruction, the war’s veterans were in need of what Gerald Linderman, author of Embattled Courage, called “hibernation”—a period of quiet when each man could reflect on his experience and try to come to terms with it. For more than a decade veterans remained quiet. Linderman explains, “Disturbing memories were to be kept to oneself, not to be aired publicly to relieve the sufferer and certainly not to correct public misapprehension of the nature of combat.”

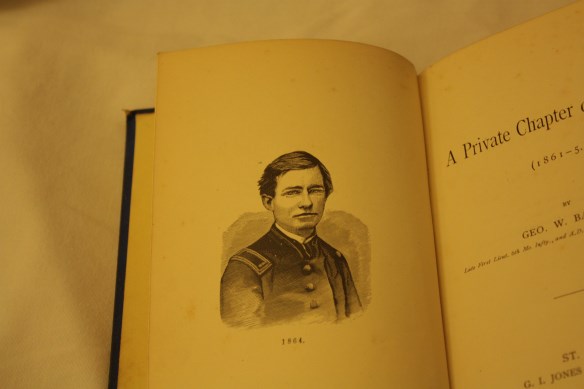

Eventually, though, what Linderman calls a “revival” began. Around 1880, commemorations, publications, and organizations of veterans proliferated. Individual soldiers told their stories, wrote their memoirs, and shared their experiences. George W. Bailey of St. Louis, Missouri wrote A Private Chapter in the War in 1880. His slim volume, he said, “presents a limited inside view of a portion of the Confederacy within its military lines, as secretly observed by a ‘stray’ from the invading army in blue, whose experiences disclose the real political sentiments of fair samples of different classes who resided within the Confederacy during the war…” He sent a copy of his book to “Gen. Jas. A. Garfield, with compliments of the author” sometime that year. It is now part of the collection in the Memorial Library at James A. Garfield NHS.

Library of Congress

Bailey, writing in the present tense, begins his story on July 22, 1864, before Atlanta, Georgia. He identifies himself as a first lieutenant and aide-de-camp on the staff of Major General Morgan L. Smith, commander of the Second Division, Fifteenth Army Corps. Captured in the midst of battle by Confederates who had overrun the Union position through an undefended railroad cut, Bailey, with perhaps eighty other officers and “a great number of soldiers” was taken under guard toward Atlanta.

“An excited rebel soldier amuses the citizen spectators by trailing one of our captured flags in the dust behind his horse…Women taunted us with, ‘Ah, boys you’ve got into Atlanta at last, haven’t you?’ Everybody seemed crazed with delight…Men, women and children gaze at us good-naturedly; but occasionally there are countenances sneering with scorn or pale with hatred.”

The Union prisoners were quickly moved out of the city, heading south, toward Andersonville.

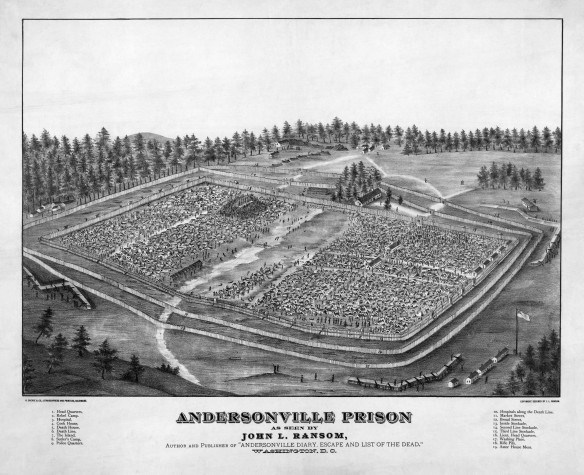

July 25. “Continued silence in the direction of Atlanta. What was the result of the battle? What does this silence mean?…One genius said, ‘The Yankees can’t fight for a while; all the live ones are busy burying the dead ones.’ (Astounding announcement—astute sentry!) How long are we going to be kept in this miserable place? How long are we to be kept on quarter-rations? Nobody seemed to know. We know that exchanges of prisoners had ceased because of a misunderstanding or disagreement concerning the status of negro troops…The gloomy prospect of Andersonville loomed up again. Horrifying contemplation. A careful mental consideration and adjustment of chances for life resulted in favor of a desperate attempt to escape, rather than attempt to survive Andersonville.”

Georgia Encyclopedia

July 26. [Bailey decides to] “escape by way of burial…Trusty comrade officers assist. Tin cup, muscles, will, calculating ingenuity, friendly suggestions, briars cut to be stacked in the earth concealing the writer and present uninviting appearance to pedestrians, …Boughs and grass were gathered; the adventurer fitted in; satisfaction. ‘All right, cover up.” First came grass and boughs, then—‘Oh, here Lieutenant, here are some things you’ll need.’ Col. Scott presented some maps (linen) of the country, rolled up in which was a small pocket-compass…A canteen was also presented, and served as a substitute for a pillow.”

Bailey was carefully concealed under earth, grass, and artfully arranged briars, with a packet of rations buried near his head. The column moved out the next morning, and a short time thereafter a hog helped itself to the buried rations. Bailey waited and listened until at least mid-day, when it began to rain and his “grave” became untenable as a hiding place. So he pushed himself up and out, and almost immediately discovered another Union soldier, a six foot tall seventeen-year-old named Lybyer. According to Bailey, when asked how the young man had escaped, his answer was “I was asleep in a brush-pile. I didn’t wake up until after they’d gone; then I thought I’d go the other way.”

On the evening of July 27th, the day of his escape, Bailey and Lybyer attempt their first contact with local slaves, which Bailey describes this way: “Hungry. Twilight; we approach the road. A mansion; negro cabins in rear. Objectives—the blacks. A whispered consultation; we are unanimous in our opinion that the blacks are our friends…” Their faith was rewarded. The two escapees were sheltered, fed and supplied by a nameless women who told the men that they were the first Yankees she had ever seen, and that they would find all the blacks in the area friendly, and could be depended upon for help.

NPS

The next day the escapees discover a substantial plantation, with several slave cabins some distance behind and not visible from the main house. They hide near a pathway until a field hand comes by. Calling out to him, they determine that again, Bailey and Lybyer are the first Yankees the slave has seen, and that the plantation’s black population will be friendly and accommodating. They are told to remain hidden until dusk, when they can be safely brought into one of the cabins.

August 1. Determining location—twenty-four miles a little east of south from Atlanta. Federal raids had caused the Confederates to closely guard every mill and cross-road of importance in the vicinity. The guards could unite in the defense of any threatened point, and they also served to prevent suspected stampedes of negroes to the Federal lines. Negroes who had recently returned from the ‘front’ reported that the Federals were expected ‘in these parts ‘fore long.’…Basing action upon the uncertainty of the situation at Atlanta and the certainty of danger ahead, and upon the fact of weariness—meaning exhaustion,–and the liability of falling into worse keeping, we concluded to remain encamped nearby until possessed of further information. The negroes clapped their hands with joy at our decision, promising to render any assistance possible.

The plantation belongs to a committed Confederate named Smith, who lives in the main house with his wife, daughters, and a son who is at home on leave from the Confederate army, recovering from a wound.

(Check back soon for Part II of this article!)

Written by Joan Kapsch, Park Guide, James A. Garfield National Historic Site, May 2016 for the Garfield Observer.