Last updated: April 3, 2023

Article

A Meddling Royal Official: Turnout at a Famous Colonial Election in Westchester County, New York

NPS

The election for an open seat in the New York assembly, held on the Village Green in Eastchester, Westchester County on October 29, 1733, is one of the better-known political events in colonial America. Two hundred and seventy-five years after the contest, historians continue to cite the election to advance various arguments about colonial life. One recent student used the election to argue for the persistent importance of monarchy in the outlook of colonists, while another scholar treated the voting as an important point in the development of political awareness among New York artisans. Many writers address the election, held at what is today St. Paul’s Church National Historic Site, in Mt. Vernon, as part of the story of the printer John Peter Zenger, whose acquittal in a seditious libel case in 1735 is seen as a foundation of the free press in America. The first issue of Zenger’s New York Weekly Journal carried a lengthy report on the famous election, producing one of the few complete accounts of a colonial election available to historians.

But how about the election itself, and especially the unusually large turnout it produced. Why would so many men -- nearly 500 in all -- come to a place 20 miles north of New York City for an election to one seat in the lower house of the New York legislature? What does that turnout tell us about the political evolution of New York in the 18th Century, and about the place of elections in the struggles for power that often defined the colony’s public life? Answers to these and related questions help shed light on the importance of the election of 1733, and particularly how the involvement of a Royal official in internal affairs could build an opposition.

We begin our story with the Royal Governor and the widespread hostility he created among the people of the colony. William Cosby made the mistake of viewing New York as merely a place to recoup his fortunes and of seeing the residents of the colony as provincials with few resources. But he did possess the means of achieving an important post in the colonies, namely connections. His wife was the first cousin of the Duke of Newcastle, who was colonial secretary.

A former soldier, Cosby arrived in the colony in 1732, after service as governor on the British island of Minorca. In the first of many acts that would generate opposition, he tried to recover half of the salary of the acting governor, Rip Van William Cosby, Royal Governor of the colony of New York in the 1730s. Dam, who had held the post for more than a year prior to Cosby's arrival. Once Van Dam refused to pay over the money, Cosby sued to recover his share, and chose the colony's Supreme Court, arranging for it to sit as an exchequer court and hear the case on the equity side.

That would seem to have improved his chances of success, since the three-member Supreme Court served at the pleasure of the governor, but it brought him into conflict with the man who would ultimately lead the opposition -- Chief Justice Lewis Morris. A man equally comfortable with wielding authority and leading an opposition, Morris had enjoyed good relationships with previous Royal Governors and had expected the same from Cosby. But here was a real conflict between a local official of considerable means who had come to see his position as legitimate and insulated against arbitrary Royal authority and the King’s representative who did not recognize local power that he could not manipulate. Additionally, in a dispute over rights to land lying between New York and Connecticut, where Morris had a distinct interest, Cosby sided with a group of rival claimants. Lewis Morris, Chief Justice of New York, 1730s.

Still confident of his authority at the time, though, Morris was prepared to confront Cosby’s intentions of using the colony for personal gain. The chief justice dismissed the case and wrote a lengthy opinion warning of the constitutional dangers of courts of exchequer. He also lectured his younger colleagues on the court - - Stephen DeLancey and Adolph Phillipse -- about the perils of such a maneuver to circumvent normal legal processes. Significantly, Van Dam’s lawyers, James Alexander, and William Smith, would soon join Morris is the opposition party. One of their first acts as a group was to arrange to have a young German immigrant printer named John Peter Zenger publish Morris’s opinion as a pamphlet.

In a rare display of good judgment, Governor Cosby wisely chose not to appeal the decision, but he could not countenance Morris’s brazen act of confrontation and he dismissed the chief from the colony’s supreme court. He appointed DeLancey, who was only 32, to take Morris’s place as chief justice, and drew closer to the DeLancey/Phillipse faction in New York politics. Rather than annoying the 52-year-old wealthy, Westchester County landowner, the dismissal galvanized Morris and freed him from the restraints of his post, allowing him to take up the banner of opposition with alacrity. Cosby certainly aided the cause against him by alienating other sectors of the colony’s pop Stephen DeLancey, who replaced Morris as Chief Justice in 1733. All of this is interesting and had the potential for a feud among a select number of men who competed for influence in the colony, but we need to broaden the discussion to understand why it became a vehicle for the political convulsion that captured the colony’s attention, highlighted by the election on the village green in October 1733.

New York had an elective, colony wide assembly since the 1690s. Turnout for most elections was modest, shaped by the systemic conditions of the day and the lack of divisive issues. These included communications difficulties, distances needed to be traveled by electors to the polling place and the lack of controversial topics. Posting was often limited to nailing a printed notice to the wall of a public building a few days before the canvass. An exception was the 10 years or so following Leisler’s rebellion of 1689, when the colony divided into recognizable pro- and anti-Leislerian blocks that competed for local and provincial offices.

But the Cosby-Morris dispute of 1733 came along at a time of important shifts in public life. Literacy was increasing and the growth of population in New York City, where the battle would be met most pointedly, created a fertile ground for political organization. And while the Royal Governor still enjoyed the great advantage of a tradition and patronage-fueled network of support, the colony was changing. Influential men, with an emerging sense of power, could take advantage of improved communication and create an independent, opposition establishment that stood at least some chance of success.

The resistance to Cosby could also draw on a relatively new set of ideas that had gained legitimacy in England as the justification for the Whig opposition to the powerful Walpole ministry, much of which came through Cato’s Letters. These were enormously influential essays by a pair of British writers -- John Trenchard and Thomas Gordon -- published in the early 1720s, and widely available and referenced in the colonies. An enduring statement of Whig dissenting thought, the essays emphasized certain key concepts, including the natural equality of men, liberty and, most importantly for our discussion, a “commitment to the natural equality of men who secured their rights and interests through the establishments of government, which was validated thereafter through the expression of electoral will.” Front page of an edition of Cato's Letters from the 1720s.

Here was an acceptable vehicle for an opposition, borrowed from the mother country, which raised the dispute with Governor Cosby and the Morris/Phillipse group, perhaps unwittingly, to the level of constitutional principle. Also useful was the Catonic sanctioned outlook of Court and Country parties which created a recognizable, if simplistic, view of political confrontation, which suited quite well the approach of the Morris party.

The most important manifestation of this newfound strength of the opposition movement was the establishment of a party newspaper, The New York Weekly Journal, which was both a cause and effect of those changes. While there had been earlier efforts to establish opposition papers, they were all short-lived and largely unsuccessful. But the New York Weekly Journal was a different kind of paper. Well-funded and intelligently edited, it was launched specifically as a clarion organ, the party press, to give voice to the opposition to a Royal Governor. In the context of New York, it was perhaps the most radical and historically important development of the period. An early edition of the New-York Weekly Journal.

While Zenger readied his press, fate set up the drama that would unfold on the Eastchester village green. The assemblyman for Westchester County, William Willett, died, setting up an open seat and what would become a hard-contested election. Assembly elections were sporadic in colonial New York, with no fixed timetables for terms or elections, and years could often elapse between full elections for the legislature.

Into this void came, quite unexpectedly, a competitive election which would serve as an open arena of combat for the emerging groups and provide former chief justice Morris with the chance to reclaim a position from which he could carry on more active opposition to the governor. In other words, he decided to enter the canvass, and the court party could hardly resist contesting the seat. They selected as a standard-bearer William Forrester, a teacher in a SPG school in Eastchester and a Royal Governor appointee as Westchester County clerk.

Something very important was a stake in the election on Monday morning, October 29, 1733, which helped produce the extraordinary turnout. The setting for the important canvass, the Eastchester town common, was ideally, centrally located. Four major roads -- the Boston Post Road, the road to Westchester Square, the Road to Mile Square, the road to White Plains -- converged on the Green, facilitating participation by interested voters from all sections of the county.

The date also contributed to the large turnout. While evenings might be cool by late October, there was no real threat of especially inclement variables and, perhaps most importantly, the harvest had been accumulated. This was, after all, an agricultural world with a voting base of farmers.

Most of the electors for Forester came through the more established landlord connections of the manors of Westchester along the Hudson River. Tenant farmers who had made sufficient improvements to their land granted on long-term lease qualified as freeholders and were eligible to vote, and the DeLancey/Phillipse faction could turn them out in large numbers. By late October most of the crop would have been harvested, certainly permitting interested participants to devote a day -- with voting and round-trip transportation -- to the cause.

Voters favoring the deposed chief justice were galvanized through the new organizational ability. A procession of men reached Eastchester by taking the Post Road south from Harrison and through the coastal sections of the county. While there was certainly a strong organization in place, this was also turnout in a manner like calling out the militia -- the party picked up strength as it marched through the towns, and gathered local men in Pelham, before meeting Morris’s supporters from the lower end of the county at the Eastchester green.

So, there they assembled on a Monday morning, and it must have been quite a spectacle for a small colonial town. Each side flexed their muscles with a show of strength, parading around the Green. The Morris side’s demonstration reflected symbols and themes borrowed from the English opposition. They were led by

two Trumpeters and 3 violines; next 4 of the principal Freeholders, one of which carried a Banner, on one Side of which was affixed in gold Capitals, KING GEORGE, and on the other, in like golden Capitals, LIBERTY & LAW; next followed the Candidate Lewis Morris Efq; late Chief Justice of this Province; then two Colours; and at sun rifing they entered upon the Green of Eaftcehfter the Place of Election, followed by about 300 Horfe of the principal Freeholders of the County, (a greater Number than had ever appeared for one Man since the Settlement of that County;) After having rode three Times around the Green, they went to the Houfes of Jophsel Fowler and – Child who were well prepared for their Reception, and the late Chief Juftice, on his alighting by feveral Gentleman, who came there to give their Votes for him.

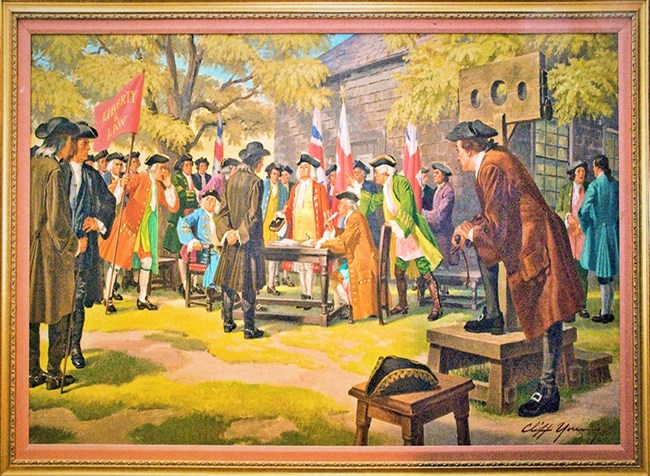

The superior organizational strength of the Morris opposition was evident in his clear majority of electors on the green that morning. But there was too much at stake to simply acknowledge the principle of larger numbers, and the Governor’s supporter would not go quietly. At the urging of the Forester party, the sheriff supervising the canvass, Nicholas Cooper, an appointee of the Governor, ordered a formal poll, with an oath attesting to the property qualification. This was an occasionally used method designed to exclude the Quaker voters, who seemed clearly in the Morris camp. For religious A 20th century painting depicting the Election of 1733, on the Eastchester green. reasons, Quakers would not swear on the bible, although they had often been permitted to affirm, an option Cooper denied them that day. As a result, in the final tally, 37 Friends were excluded, but Morris still won a comfortable victory.

Recognizing that this was just part of a larger political struggle, the affair ended amiably, with the traditional congratulations offered all around. Morris was escorted back to New York City where he was given a hero’s welcome.

Conclusion: So, what did the election demonstrate? It showed, for one thing, that elections could produce considerable turnouts when they were understood to be part of a larger struggle. Additionally, the machinery of mobilization and concentration grew to meet the requirements of turning out large numbers of men. Between Morris’s dismissal as chief justice in August and the October election, the opposition to Cosby had been organizing, and, obviously, already set up an impressive system when the death of Assembly member William Willett created the unexpected opening for a contest.

But perhaps something else was at stake and helped generate the large turnout. While Royal Governors in colonial New York held tremendous symbolic and real power, they rarely became directly involved in local politics. An extremely unlikable figure, Cosby was almost a caricature of an interfering, outside Royal governor who cared little about effective administration of the colony and was clearly only out for himself. He could easily be resented by sizable portions of the New York population, who were, perhaps, just beginning to develop a sense of identity and confidence in their legitimacy.

The widespread opposition to Cosby, particularly in New York City, would lead to a popular petition drive to oust him and had a lot to do with the eventual acquittal of Zenger in the famous trial in 1735. But even in 1733, his interference and disdain for the local population was probably strong enough that once it was clear he had become involved in the election, handpicking Forester as the candidate to oppose Morris, the popular cause picked up momentum. The turnout was not really caused by antiauthoritarianism, or any modern understanding of democratic populist impulse. Morris and his colleagues were drawn from the same elite sector of the population as the DeLancey/Phillipse party. But neither should we dismiss some of the Catonic slogans used by the New York Weekly Journal and in campaign materials. To a considerable extent, they reflected the outlook of an organization looking for legitimate means to combat an over-reaching executive against whom they had little recourse.

In that light, the organizational strength, and the large turnout it helped produce were an early, if dim, forecasting of the strategies used by the Whigs in the period of the Imperial Crisis of the 1760s and 1770s, which presaged the American Revolution.