Part of a series of articles titled Park Paleontology News - Vol. 17, No. 1, Spring 2025.

Article

A mammoth donation and nearly 50 years of fossil discovery at Waco Mammoth National Monument

By Lindsey T. Yann, Ph.D., Paleontologist, Waco Mammoth National Monument

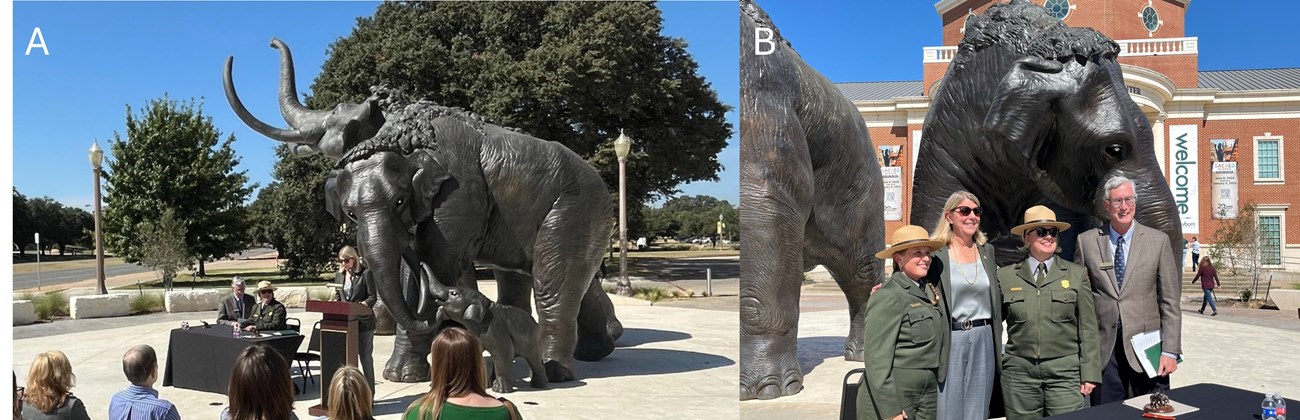

On October 21, 2024, Baylor University’s President Linda Livingstone joined staff from the National Park Service and Baylor’s Mayborn Museum Complex for a signing ceremony officially donating the Waco Mammoth Site collection to Waco Mammoth National Monument. In addition to thousands of fossils and their data, the collection includes archived photographs, slides, and research documents covering the history of the site. On October 21, 2024, Baylor University’s President Linda Livingstone joined staff from the National Park Service and Baylor’s Mayborn Museum Complex for a signing ceremony officially donating the Waco Mammoth Site collection to Waco Mammoth National Monument. In addition to thousands of fossils and their data, the collection includes archived photographs, slides, and research documents covering the history of the site. The photographs below show the ceremony, taking place in front of the new bronze sculptures at the Mayborn Museum Complex. Baylor University President Dr. Linda Livingstone spoke on the importance of the collection before signing the donation documents (Figure 1A). Baylor University and National Park Service staff pose in front of the museum after the signing (Figure 2B). From left to right: Dr. Lindsey T. Yann (WACO paleontologist), Dr. Linda Livingstone (Baylor University President), Christine Jacobs (Acting WACO Superintendent), and Charles Walter (Baylor University Mayborn Museum Complex Director).

Photographs by NPS park guide Brandon Kenning

Nearly 50 years of discovery led to this collaborative event. Waco Mammoth National Monument was first known as the Waco Mammoth Site, after the discovery of a Columbian mammoth (Mammuthus columbi) bone in 1978. Staff from Baylor University’s Strecker Museum (now Mayborn Museum Complex) directed the excavation, which quickly expanded into an entire quarry of approximately 16 mammoths in varying degrees of articulation. By 1990, museum staff determined the mammoths needed to be removed if they were to be saved. The team wrapped the fossils in protective plaster jackets, which were lifted by crane to a flatbed truck. Once the jackets were moved to a Baylor University warehouse, museum staff began to clean the excavation site.

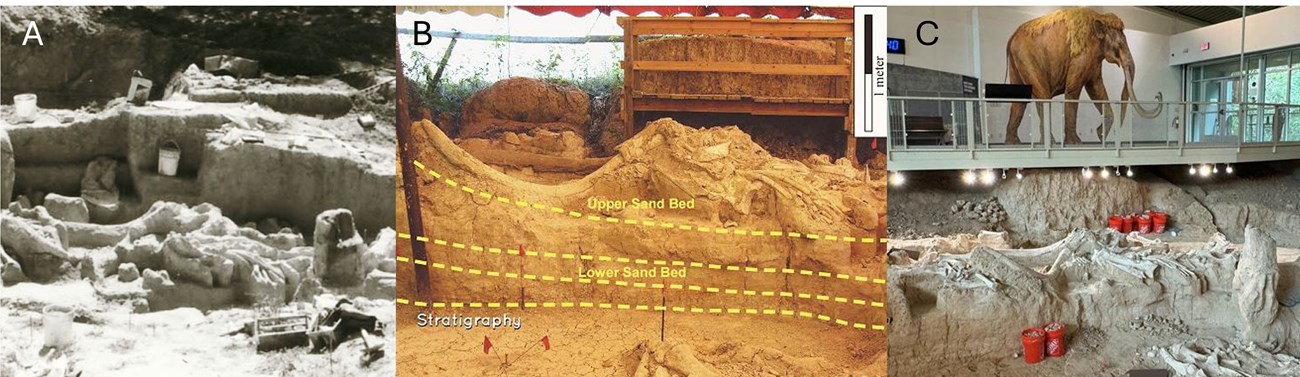

Figure 2 shows early phase one excavations at Waco Mammoth Site (1978–1990). In Figure 2A, Dr. John Fox (left), past Anthropology faculty, and an unknown volunteer (middle), assist Baylor University Strecker Museum’s David Lintz (right) with excavation. In Figure 2B Strecker Museum director Calvin Smith (seated among mammoths) speaks with visitors.

Figure 2 shows early phase one excavations at Waco Mammoth Site (1978–1990). In Figure 2A, Dr. John Fox (left), past Anthropology faculty, and an unknown volunteer (middle), assist Baylor University Strecker Museum’s David Lintz (right) with excavation. In Figure 2B Strecker Museum director Calvin Smith (seated among mammoths) speaks with visitors.

Photographs from the original Baylor University archives.

While cleaning the site, a backhoe hit more bone, and a second phase of excavation began. By the early 1990s, the site had five more mammoths, and it became clear that additional help was needed to preserve the site. Excavation stopped in 2002, and attention turned to fundraising for a building and pursuing National Monument status. During this time, land ownership changed, and partnerships were established to support the growing Waco Mammoth Site.

Figure 3 shows the progression of the phase two excavations highlighting the large male, mammoth Q. Phase two uncovered at least seven more partial mammoths (Figure 3A). In order to better protect the fossils, several large tents were used to cover the mammoths (Figure 3B). The Dig Shelter opened in 2009 and is now viewable to visitors at Waco Mammoth National Monument (Figure 3C). Measurements from mammoth Q were used to create the mural above the skeleton.

Figure 3 shows the progression of the phase two excavations highlighting the large male, mammoth Q. Phase two uncovered at least seven more partial mammoths (Figure 3A). In order to better protect the fossils, several large tents were used to cover the mammoths (Figure 3B). The Dig Shelter opened in 2009 and is now viewable to visitors at Waco Mammoth National Monument (Figure 3C). Measurements from mammoth Q were used to create the mural above the skeleton.

Images A and B are from the original Baylor University archives and Image C was taken by Dr. Yann.

The site first opened December 2009 as a park operated by the City of Waco Parks and Recreation, in cooperation with Baylor University and with assistance from the Waco Mammoth Foundation. After several setbacks, the site officially became Waco Mammoth National Monument on July 10, 2015. The enabling legislation established a collaborative partnership between the NPS, City of Waco, and Baylor University, with philanthropic support from the Waco Mammoth Foundation. The enabling legislation also required the donation of all fossils and associated documents from the Waco Mammoth Site.

The monument was established to inspire visitors, foster a learning environment, and support ongoing research to preserve and protect the remains of the first known Columbian mammoth nursery herd. The main group of fossils consists of adult females and their offspring, which died approximately 65,000 years ago. Most of the females are 20–30 years old, and the juveniles are 3–8 years old, but a recent discovery suggests there may be younger individuals in the collection. The deposits are effectively monodominant, meaning almost all the site’s fossils are of the same species, Columbian mammoths. However, the site also includes an in-situ skeleton of a Western camel (Camelops hesternus). Scientists also discovered isolated bones of bison (Bison sp.), horses (Equus sp.), dwarf pronghorns (Capromeryx minor), a coyote (Canis latrans), a juvenile saber- or dirk-toothed cat (Smilodon or Homotherium), an American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis), an alligator snapping turtle (Macrochelys temminckii), map turtles (Graptemys sp.), freshwater drum fishes (Aplodinotus grunniens) and a few unidentified small mammals, turtles, fish, birds, and lizards.

Thanks to the dedication of Baylor University staff and volunteers, all fossils discovered at the site remain in Waco, Texas. In-situ specimens are on display at Waco Mammoth National Monument, and all the newly donated specimens are housed in the state-of-the-art Geosciences Collection at the Mayborn Museum Complex. Although the donation gave legal ownership of the material to the National Park Service, Baylor University and the Mayborn Museum Complex continue to be stewards of the material as the site’s official repository.

We have been working together over the last three years to assess research needs and recruit graduate students, but the condition of the collection itself has made research difficult. Each phase of excavation lasted about ten years (1978–1990 and 1990–2002) without proper protection from the elements. The fossils were, and some still are, preserved in a calcite-cemented, shrink-swell clay in an area referred to as “Flash Flood Alley.” The combination of severe storms, distinct wet and dry seasons, and inadequate protection negatively impacted the fossils.

The jacketed material remained in the warehouse until the Mayborn Museum Complex opened in 2005. Once the material was moved into collections, the fossils were organized by individual mammoths to the best of the staff’s ability. Due to incomplete notes and maps, plus many years of flood damage, it is difficult to determine which fragments belonged to which individual. Since the donation, NPS volunteers and Baylor University students have been assisting the NPS by reconstructing the fossils. As an example of how fragmented some specimens are, an approximately 3-foot-long humerus (upper arm bone) from a female mammoth was rebuilt using hundreds of fragments from 15 boxes spread throughout five different museum cabinets. Efforts to rebuild the collection are time-consuming but ongoing. In the meantime, we also support student research focused on a better understanding of the late Pleistocene community in central Texas.

The monument was established to inspire visitors, foster a learning environment, and support ongoing research to preserve and protect the remains of the first known Columbian mammoth nursery herd. The main group of fossils consists of adult females and their offspring, which died approximately 65,000 years ago. Most of the females are 20–30 years old, and the juveniles are 3–8 years old, but a recent discovery suggests there may be younger individuals in the collection. The deposits are effectively monodominant, meaning almost all the site’s fossils are of the same species, Columbian mammoths. However, the site also includes an in-situ skeleton of a Western camel (Camelops hesternus). Scientists also discovered isolated bones of bison (Bison sp.), horses (Equus sp.), dwarf pronghorns (Capromeryx minor), a coyote (Canis latrans), a juvenile saber- or dirk-toothed cat (Smilodon or Homotherium), an American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis), an alligator snapping turtle (Macrochelys temminckii), map turtles (Graptemys sp.), freshwater drum fishes (Aplodinotus grunniens) and a few unidentified small mammals, turtles, fish, birds, and lizards.

Thanks to the dedication of Baylor University staff and volunteers, all fossils discovered at the site remain in Waco, Texas. In-situ specimens are on display at Waco Mammoth National Monument, and all the newly donated specimens are housed in the state-of-the-art Geosciences Collection at the Mayborn Museum Complex. Although the donation gave legal ownership of the material to the National Park Service, Baylor University and the Mayborn Museum Complex continue to be stewards of the material as the site’s official repository.

Building a research collaboration

Thanks to close proximity and a well-established partnership, Waco Mammoth National Monument and Baylor University are working together to preserve these specimens and establish a robust research program. In addition to the Mayborn Museum’s repository work, the university’s Department of Geosciences is supporting research at WACO. I started with the NPS in January 2020, just before COVID shut down both NPS and Baylor University. In 2021, I was asked to join Baylor University Graduate Faculty as a Visiting Scholar in the Department of Geosciences. This position has given me the opportunity to co-advise a Ph.D. student and two M.S. students with Dr. Dan Peppe. Our first co-advised M.S. student will graduate May 2025, and a new Ph.D. student will be joining the lab in August 2025.We have been working together over the last three years to assess research needs and recruit graduate students, but the condition of the collection itself has made research difficult. Each phase of excavation lasted about ten years (1978–1990 and 1990–2002) without proper protection from the elements. The fossils were, and some still are, preserved in a calcite-cemented, shrink-swell clay in an area referred to as “Flash Flood Alley.” The combination of severe storms, distinct wet and dry seasons, and inadequate protection negatively impacted the fossils.

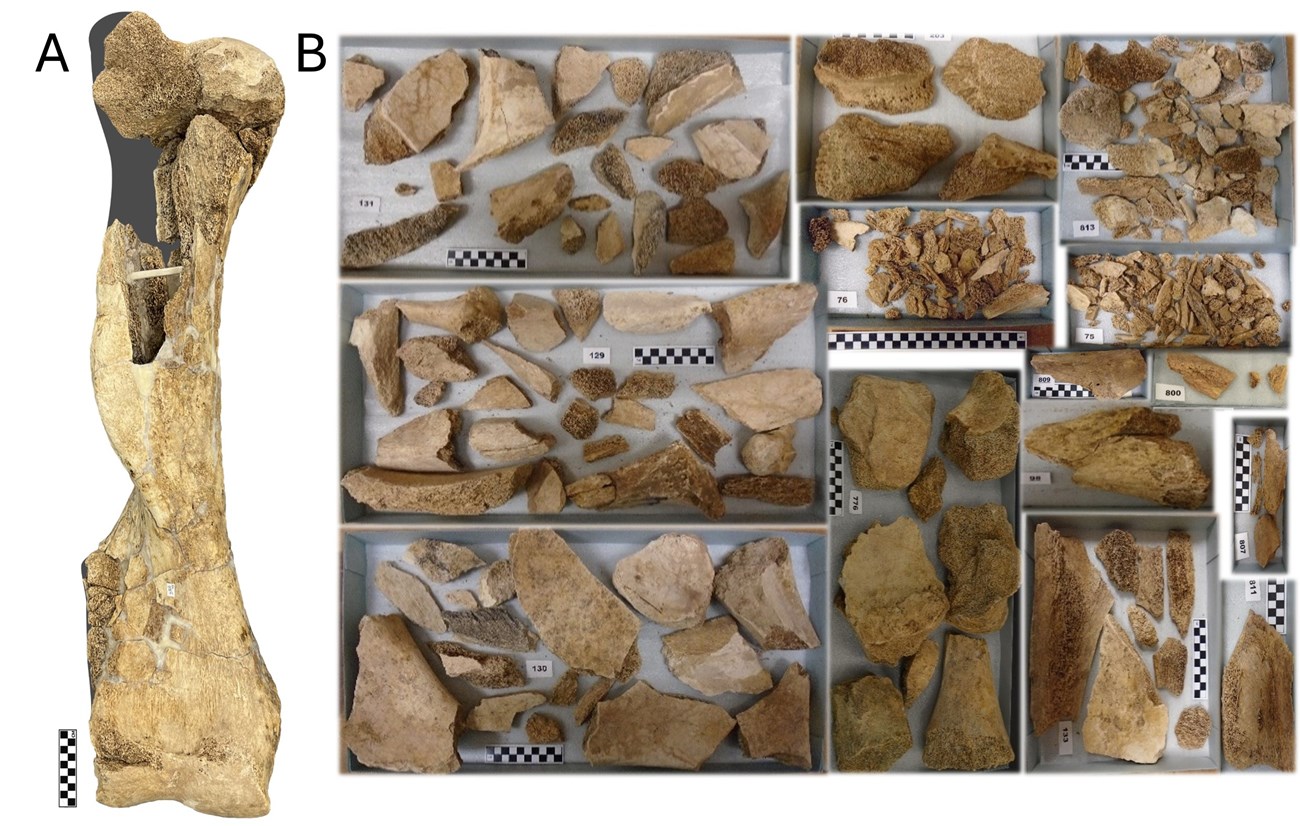

The jacketed material remained in the warehouse until the Mayborn Museum Complex opened in 2005. Once the material was moved into collections, the fossils were organized by individual mammoths to the best of the staff’s ability. Due to incomplete notes and maps, plus many years of flood damage, it is difficult to determine which fragments belonged to which individual. Since the donation, NPS volunteers and Baylor University students have been assisting the NPS by reconstructing the fossils. As an example of how fragmented some specimens are, an approximately 3-foot-long humerus (upper arm bone) from a female mammoth was rebuilt using hundreds of fragments from 15 boxes spread throughout five different museum cabinets. Efforts to rebuild the collection are time-consuming but ongoing. In the meantime, we also support student research focused on a better understanding of the late Pleistocene community in central Texas.

Photographs courtesy National Park Service.

Baylor University Department of Geosciences Student Research

Ashely Gonzalez, a M.S. student, defended her thesis in early April 2025, focused on the stratigraphy and geochemistry of a paleosol preserved within the Dig Shelter at WACO. She discovered that Baylor University staff, students, and volunteers unknowingly uncovered at least three discrete late Pleistocene fossil deposits. Based on sediment grain size analyses, evidence from the layering of the strata, and recent studies of the site’s taphonomy (the processes affecting a future fossil between death and fossilization), the three deposits were preserved on a floodplain away from the river channel. Here, clay- and silt-sized sediments eventually buried the carcasses after minimal reworking and transport. Geochemical data were used to estimate paleo-temperature and precipitation, and results indicate the mammoths lived and died during a dry sub-arid to sub-humid climate, approximately 43.7 ºF (6.5 ºC) cooler than today.These results indicate the previous hypothesis that the mammoth remains within the Dig Shelter at WACO represent a single depositional event during a major flood is implausible. Instead, the data favor the hypothesis that the fossils in the WACO Dig Shelter represent multiple attritional death assemblages (taking place over time instead of single catastrophes) of animals that lived and died in a cool, dry, sub-humid to semi-arid climate. Additional work is still needed to understand the nursery herd and associated fossils uncovered in the first phase (1978–1990) outside the present Dig Shelter.

Recent sampling within the Waco Mammoth National Monument Dig Shelter resulted in a simplified stratigraphic profile with the location of three fossil horizons indicated by black circles (Figure 5A). Layer 1 contains the original nursery herd of ~18 Columbian mammoths and a Western camel. Layer 2 contains a bull mammoth with a juvenile draped over the tusks. Layer 3 contains an articulated female and an isolated pelvis. In Figure 5B, Dr. Yann and intern Phoenix Orta assist M.S. student Ashley Gonzalez by sampling right below the original location of the isolated male pelvis in Layer 3.

Figure and image by Ashley Gonzalez.

Dava Butler, a Ph.D. candidate, is actively investigating three topics: 1) new preparation methods to stabilize highly fragmented Quaternary fossils for X-ray and CT scanning; 2) documenting records of stress within the Columbian mammoths preserved at WACO, and 3) documenting and describing the youngest individuals found hidden within the WACO collection. Her work on the first two topics has been presented at recent Society of Vertebrate Paleontology meetings and at the 2024 North American Paleontological Convention. Thanks to new methods using kozo paper, acrylic rods, and Paraloid B-72, she successfully had specimens from several individuals survive both X-ray and CT scanning. Her final year will be focused on submitting manuscripts on the first two topics and then switching gears to document the youngest individuals at WACO.

Maree Yard, a M.S. student, is working to determine how many mammoths are preserved at WACO. She has already finished data collection and accepted a full-time position with Triebold Paleontology, Inc. in Woodland Park, Colorado. Over the next few months, she will be working to finish her thesis for submission to the Graduate School.

Stay tuned for more information that completely rewrites what we know about Waco Mammoth National Monument!

Maree Yard, a M.S. student, is working to determine how many mammoths are preserved at WACO. She has already finished data collection and accepted a full-time position with Triebold Paleontology, Inc. in Woodland Park, Colorado. Over the next few months, she will be working to finish her thesis for submission to the Graduate School.

Stay tuned for more information that completely rewrites what we know about Waco Mammoth National Monument!

Last updated: May 16, 2025