Last updated: January 10, 2024

Article

A Hester Bateman Teapot at Val-Kill

Silver teapot that once belonged to Eleanor Roosevelt with the mark of Hester Bateman, London, 1782. Eleanor Roosevelt National Historic Site.

Hester Bateman is one of the most celebrated silversmiths of the 18th century. She likely began her career in her husband's workshop before establishing her own successful business—a surprising accomplishment given long-standing, gender divisions throughout history. The centrality of family-based enterprises for women—housewifery, as it was called in the 17th century—have biased our understanding of women’s experiences in the history of labor until more recently. Imagine William Hutton’s surprise in 1741, when traveling through the English countryside he passed a blacksmith’s shop with “one or more females, stripped of their upper garments, and not overcharged with the lower, wielding the hammer with all the grace of the sex.” Finding women working a trade usually practiced by men was more shocking to Hutton than the women’s lack of clothing.1

Historians estimate that there may have been over 60 female silversmiths working in London between 1700 and 1850. That figure is unreliable, based only on those women who successfully registered a hallmark with the Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths, founded in 1327 to regulate the craft and trade of gold and silver. It’s important to remember that survival may have necessitated the involvement of women in a family business, even if they weren’t working at the bench.2 “No one contested the right of wives and daughters to work in a shop or at a stall leased in the name of the husband and father,” writes Olwen Hufton in The Prospect before Her: A History of Women in Western Europe, 1500-1800. “The tendency of a master in an occupation where there was scope for the employment of his daughter—particularly if he had no sons—may have been to familiarize her with the techniques of the trade. At the humblest levels, where the master in question did not employ journeymen and where any apprentices kept quiet, then the master's daughter unofficially may have done much work without incurring opposition from the guild.”

Women have been left out, or at best marginalized, in telling the history of labor and craftsmanship. Most have been forgotten, but Hester Bateman is remembered for the large amount of surviving silver that bears her hallmark and shrewd business practices integrating new technology in the production. Her legacy as a master craftsman has endured through the centuries but may not be entirely correct. She was likely more entrepreneur than artisan.

Hester Bateman's hallmark.

Born Hester Needham in 1709, she had no formal education. Hester married John Bateman (d. 1760) in 1732 and had five children—two girls and three boys. John Bateman is sometimes identified as a silversmith or goldsmith, but he was actually a wire-drawer and chain-maker (a branch of the silversmith’s art), primarily crafting watch chains—not so illustrious but a source of steady work and reliable income. The Goldsmith’s Company exempted chains from marking and may account for the absence of a trademark registered in his name.

John Bateman died on November 13, 1760, leaving “unto my loving wife . . . all my household goods and implements.” The following year, Hester registered her own mark at Goldsmiths’ Hall—an HB in script. Membership in guilds and companies was strictly regulated. Specific qualifications and strict rules governed the process to register a hallmark. This typically included fulfilment of an indenture with a binding term usually lasting seven years. Two of the Bateman sons, Peter (b. 1740) and Jonathan (b. 1747), were apprenticed to their brother-in-law Richard Clarke, a London goldsmith who married their sister Letticia in 1755. When the term was complete, the “binding” to the master was broken, and the apprentice became a freeman of the company that registered the indenture. Though rare, some women were made free by their own apprenticeship. However, special provisions allowed a widow to register a hallmark upon the death of her registered husband, and the evidence of Hester’s trademark raises questions regarding John Bateman’s membership status. With two sons and one son-in-law working in the trade, John, and later Hester, may have relied on their children’s status as goldsmiths. Peter was not made free until 1762. And both sons are not registered (in partnership) prior to Hester’s retirement in 1790.3

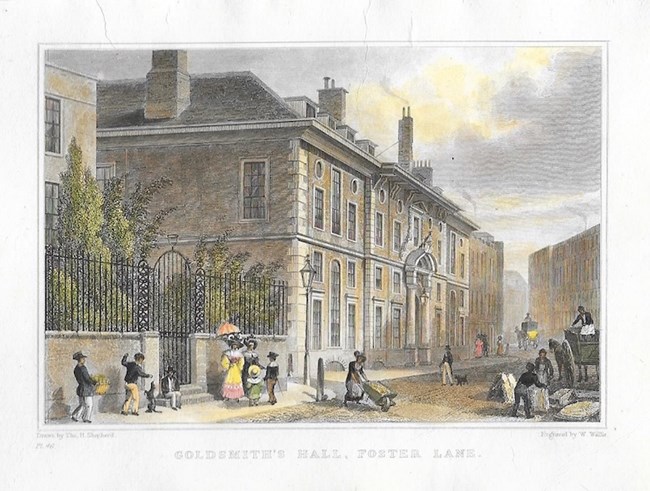

Goldsmiths Hall, headquarters of London’s goldsmith guild. This is the second Goldsmiths Hall as it appeared in Hester Bateman’s lifetime. The building was erected about 1634 and demolished in the 1820s.

Over the next thirty years, with her sons Jonathan and Peter and her daughter-in-law Ann, Hester Bateman built a thriving family business. Hester’s early output consisted mainly of domestic spoons and forks, representing nothing of merit, but a significant departure from her husband’s watch chains. The workshop soon began making teapots and coffee urns. This expansion coincides with the development of machine production, providing economies in decorative borders and motifs as well as the production process. Insurance documents for 1802 reveal that the shop, with its own steam operated flatting mill, was one of the most technologically advanced in London.4 These advances allowed her to maintain a constant inventory, producing a wide range of items from elegant tea sets and flatware to ornate candelabras and inkstands. Her utilization of factory-made components and machine processes in decoration produced large quantities of stock at affordable prices. Bateman silver was exported to retailers and customers all over England and North America. When she retired in 1790, Hester Bateman’s workshop had produced thousands of examples. That same year, her son Peter registered a mark with his brother Jonathan. Representing only four months of production, silver wares with the Peter and Jonathan Bateman hallmark are among the rarest and most sought after. Jonathan died only weeks into the partnership. Peter and Jonathan’s widow, Ann registered a joint hallmark in 1791 and continued in partnership until 1799 or 1800 when Ann’s son William joined the workshop. The Bateman dynasty advanced through the London silver trade for four generations into the mid-19th century.

A possible example of Hester Bateman’s North American exports is a silver teapot that belonged to Eleanor Roosevelt. The history of the teapot prior to Eleanor Roosevelt’s possession is unknown, but we presume, like much of her silver used at Val-Kill, it was inherited through succeeding generations of the Roosevelt or Hall families. The teapot’s oval form with flush-hinged cover, thin beaded rims, and flat chasing are indicative of the Bateman style.

Although the connection between Hester Bateman and Eleanor Roosevelt may seem as insignificant as afternoon tea, a teapot with the mark of Hester Bateman in the dining room at Val-Kill invites us to consider the gender associations with this highly recognizable and popular form of holloware. The introduction of tea into England at the end of the 17th century instituted new social practices and a range of silver commodities equal in value—sugar bowls, sugar tongs, creamers, tea caddies, tea strainers, teaspoons, and of course, teapots—all of which were produced and sold in the Bateman workshop. Tea was far too expensive and precious to be entrusted to a servant for brewing.4 Preparing and serving tea became the responsibility of the lady of the house as observed in eighteenth-century illustrations that portray the custom. By the 19th and well into the 20th century, tea and teapots were associated with the female domain.5 It is fitting then, although there is no evidence she employed the statement, that Eleanor Roosevelt is often credited as saying “A woman is like a tea bag. You never know how strong it is until it’s in hot water.”6 In this instance, however, tea represents an ironic twist of a tenacious gendered symbol. In the person of Eleanor Roosevelt, tea epitomizes a woman who surpasses the trappings of wealth and privilege to become a feminist icon dedicated to labor legislation, equal pay and education for women, women’s representation in the Democratic Party, public housing, civil rights, and international peace.

In an example by Hester Bateman, a silver teapot can represent historical associations of occupational segregation and the devaluation of women’s work. In its final setting at Val-Kill, more than two hundred years after it was made, we might consider this teapot as emblematic of both women’s legacies. Hester Bateman’s success is credited to her perseverance and business acumen. Just as Eleanor used her connections to widely market Val-Kill Industries furniture and pewter, or reinvent the role of First Lady, Hester was a skilled marketer using her connections in the London trade to attract wealthy clients across Europe. She was also an innovator, constantly seeking new designs and techniques to keep her work fresh and appealing. She grew and expanded her business, employing apprentices and family members to help with production. Perhaps most impressive of all, Hester Bateman achieved this at a time when women were largely excluded from the formal trades and professions, a status that remained largely unchanged until the later years of Eleanor Roosevelt’s life. Hester Bateman’s story is one of women in history who pursued independence, overcame obstacles, and expanded opportunities for the women who followed them. Her legacy is so much more than that of a master silversmith. It is a symbol of what women can achieve when given the opportunity to excel in their chosen fields.

Frank Futral

Curator, Eleanor Roosevelt National Historic Site

Endnotes

1 Quoted in John William Willis-Bund and William Page, eds., The Victoria History of the County of Worcester, Volume Two, (London: Archibald Constable and Company Limited, 1906), 272, fn. 5.

2 For example, it was not uncommon for women to be employed as finishers or burnishers. See Philippa Glanville and Jennifer Faulds Goldsborough, Women Silversmiths, 1685-1845, Works from the Collection of The National Museum of Women in the Arts (Thames and Hudson, 1990), 17-18.

3 David McKinley, “Apprenticeship and Freedom for the English Goldsmith,” for the Association of Small Collectors of Antique Silver.

4 For this reason, it is not uncommon to find locks on 18th-century tea caddies.

5 Philippa Glanville and Jennifer Faulds Goldsborough, Women Silversmiths, 1685-1845, Works from the Collection of The National Museum of Women in the Arts (Thames and Hudson, 1990), 51-54.

6 Archivists at the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library in Hyde Park, New York and historians have searched for the expression in the writings of Roosevelt and have not found it.