Last updated: December 7, 2022

Article

A Family of Service

National Cemetery.

NPS Photo

Each spring, as blooming trees and blue skies return to Gettysburg National Cemetery, many are drawn into the walkways of this historic place. Within the walls of the cemetery, thousands of those who served their country rest amidst walkways, memorials, and grass covered slopes on Cemetery Hill. On the southern slopes of that hillside sits Section 3 of the Gettysburg National Cemetery, as well as a memorial to Abraham Lincoln’s famed Gettysburg Address. In the shadow of this memorial, on this peaceful hillside, there sits row after row of headstones, each telling a separate story in simple white marble. Amidst these rows of headstones, there is one that reminds us of the connections between generations past and present, how intertwined the stories of history are, and the various ways we can serve our country and each other. It is the headstone for Robert and Dorothy McCormick.

Robert and Dorothy were many things. They were husband and wife. They were father and mother to a family of six children. And they were also veterans of the United States Navy during World War II. Fittingly enough, they were married on November 11, 1948, a day known then as Armistice Day, and known now as Veterans Day. For a couple with multiple connections to the American armed forces, it was an appropriate wedding date.

Robert McCormick was a native of Wilkes Barre, Pennsylvania, born on Christmas Eve, 1917. He was well educated, attending the Philips Andover Academy, Yale University, and the Harvard Business School. During World War II he served as an officer in the United States Navy, and he also held numerous positions with the Federal government. After the war, he met Dorothy Bragdon in Washington, D.C.

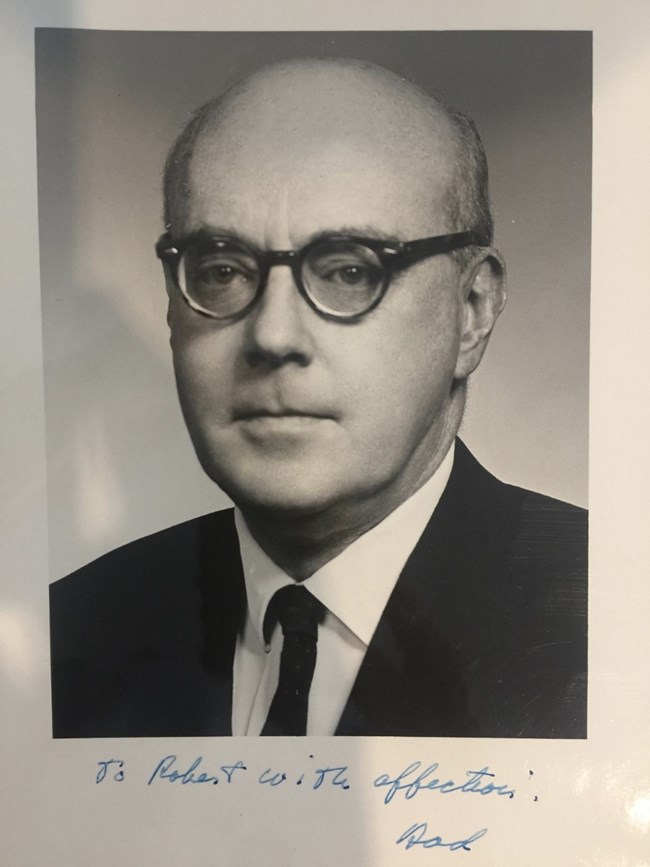

Courtesy of the McCormick Family

Born March 31, 1922, in Pittsburgh, PA, Dorothy was a college graduate as well, having studied at Brown University and the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. Dorothy’s education made her an ideal candidate to serve during World War II in a new, pioneering role.

World War II saw many new opportunities for service, and women answered the call with great fervor and passion. In 1942, the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) was created—two months later, the Navy and Marines added women to their ranks as well with the Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service, known as WAVES. Ultimately, several other new branches were formed, and all told, over 350,000 women served in the United States armed forces during World War II.

For Dorothy, the United States Navy was the way to go. Her college education made her an excellent candidate to serve as one of the 8,000 WAVES officers. Within the first year, there were over 27,000 enlistees in WAVES, and over 80,000 over the course of the war.

During the war Dorothy reached the rank of Lt. Junior Grade. She was a proficient marksman, and gained the nickname “Pistol Packin’ Mama”, according to her family. Her wartime service saw her stationed in Charleston, SC, and Hawaii, and even went on to work in the Office of Strategic Services, the wartime precursor to the CIA.

As was the case for so many, the post-war years saw life change significantly for Robert and for Dorothy. After their wedding, Robert continued in the Federal government, working on the First and Second Hoover commissions, as well as working for the Republican National Committee.

Courtesy of the McCormick Family

Dorothy, on the other hand, took a different path; she started a school for local children in her own home, calling it the Country Play School. When the school outgrew her home, she established the Country Day School, in McClean, VA, which is still in operation today. In addition to her work at the school, Dorothy earned a master’s degree, and received numerous professional awards, becoming known as a pioneer in early childhood education.

Robert and Dorothy remind us of those who, once World War II came to an end, came home and built lives for themselves. Much like Dwight Eisenhower, these veterans did not stop their service once they were discharged from the military—they found ways to continue making an impact in civilian life. While some, like Dwight Eisenhower, John F. Kennedy, and George H.W. Bush went on to become Presidents of the United States, many others worked in different areas of civilian life. For Dorothy McCormick, her post-war service was found in educating children, having an impact on countless children and their families.

Veterans continuing to serve others in their civilian lives is not unique to the World War II generation—from the Revolution to modern wars in the Middle East, there have been untold veterans whose impact was felt not just in the ranks, but in the lives of their family members and their communities as well.For the McCormicks, though, there is another chapter of their story that reminds us of the ways we are connected to the past. This part of the story lies with Dorothy and her family.

Born Dorothy Bragdon, Dorothy McCormick's father was John Stewart Bragdon, who was a member of the West Point Class of 1915, one of the most decorated and acclaimed in the history of the U.S. army. That class saw 59 of its graduating members go on to reach the rank of general. John Stewart Bragdon was one of those, and so was a young man from Kansas—Dwight David Eisenhower.

Courtesy of the McCormick Family

That right. Dorothy’s father was a West Point classmate and personal friend of Dwight Eisenhower. Indeed, during the 1930s, they served together in the Philippines on the staff of General Douglas MacArthur. While Ike brought his wife Mamie and their son John, John Stewart Bragdon brought his family as well, including young Dorothy. Much like Eisenhower, Bragdon went on to become a general during World War II, though instead of overseeing the Allied invasion of Europe, Bragdon worked stateside in Washington as an engineer and, by 1944, he served as the Director of Military Construction for the army. He continued work as an engineer in the army until 1951, when he left the military for the private sector before joining the Eisenhower administration as a special advisor. One of his biggest projects was working on the implementation of the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956, developing the interstate highway system in the United States.

Bragdon’s relationship with Eisenhower was more than a professional acquaintance or partnership. From their days as cadets at West Point to working together in the White House, Bragdon and Eisenhower had a personal and professional relationship that spanned over five decades. As evidence of their personal ties, Bragdon was part of an effort by White House staff to gift the Eisenhowers two pine trees for planting at their Gettysburg farm, for which the President sent a thank you note in the summer of 1959 (the note even included a map showing the route from Washington to their home in Gettysburg).

General John Stewart Bragdon died in 1964, and is buried in the West Point cemetery in New York. His son in law, Robert McCormick, passed away in 1975, and as a veteran, was eligible for burial in the Gettysburg National Cemetery, along with thousands of other veterans who are interred here. Dorothy passed away in April of 2018, and interred alongside Robert in Section 3 of the Gettysburg National Cemetery.

Courtesy of the McCormick Family

The story of John Stewart Bragdon, his daughter Dorothy, and her husband Robert McCormick, reminds us of the incredible connections we find among individuals in history. That one day Robert and Dorothy would come to be buried in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, near where their father’s friend and West Point classmate Dwight Eisenhower owned a home, and on the same Cemetery Hill that Eisenhower frequented throughout his time in Gettysburg, reminds us of this incredible link. These two families were brought together by shared ideals and the common notion of public service, both in times of war and in peace. They served in World War II, and in the war’s wake, they worked to improve their country and communities, either by working in government, or, in Dorothy’s case, starting a school and educating children.

Much as Robert and Dorothy’s tombstone sits near the Lincoln Gettysburg Address memorial, their lives and connections to World War II remind us that service is something we can all engage in. When Lincoln spoke on Cemetery Hill in November 1863, he reminded the American people that even in the wake of the Union victory at Gettysburg, there was still “unfinished work” and “a great task remaining before us.” For those who served in World War II—for Robert McCormick, for Dorothy Bragdon, for John Stewart Bragdon, for Dwight Eisenhower, and for the millions of other veterans of World War II, there was a great task remaining before them when the war came to a close. They had defended democracy as soldiers, sailors, and airmen at war, and would work to perfect it as civilians in a time of peace.