Last updated: March 3, 2024

Article

A Family Affair

Yosemite National Park hired a handful of women as temporary rangers in the 1920s. Like those at Yellowstone National Park, most had family connections to the park that made them well suited to work in remote areas.

Marriages of Convenience (for the NPS)

To combat isolation, meet staffing needs, and maximize available housing, Yosemite hired some rangers’ wives as temporary rangers during busy seasons. Like other rangers, they collected fees, sealed guns, made sure dogs were leashed, registered cars at the park’s entrance stations, and responded to emergencies as needed.

One of the earliest women rangers in the park was Jessie B. Reed. Her husband Ernest began working at Yosemite on August 6, 1918, at the Bridalveil Falls checking station. She became a temporary ranger at the park on June 23, 1919, working about seven weeks that summer. The 1920 US Census lists her occupation in April that year as “assistant ranger” but her personnel record lists her occupation as cook, which was her winter job. She did work as a temporary ranger position from July to October that year. She worked as a ranger again in 1921 but wasn't employed by the park in 1922.

In 1923 she worked again as a cook. She wasn't paid by the NPS again until 1927. However, as a ranger's wife she undoubtedly continued to assist him even without pay. In 1927 she was a temporary ranger for the summer but in 1928 she was a ranger for only four days but Ernest continued to work as a ranger. In 1937 their cabin was damaged by flooding. They contined to live in the park until Ernest died in 1939. She relocated to Santa Barbara to operate a hotel business. Jessie Reed died in 1957, aged 83.

Ranger Beatrice Freeland, 25, and her husband Edward worked at the park’s Bridalveil Falls and Alder Creek entrance stations during the summers of 1923 and 1924, respectively. Together, they provided the coverage to check cars 16 hours per day, seven days a week. Ranger Martha Bingaman, 35, and her husband John took over at Alder Creek in 1926. She worked for two months that first year, followed by three months in 1927 and three more in winter 1928. She earned $135 per month from which $15 per month was deducted for housing costs.

Ranger Eva McNally, 21, and her husband Charles both worked as temporary park rangers during the summers of 1926 and 1927 at the Tuolomne Meadows and Aspen Valley ranger stations, respectively. She recalled that she brought home 50 cents more per month than he did, as the $1 health insurance premium came out of his paycheck.

Yosemite likely hired other women rangers who are less well documented. McNally vaguely recalled the Smiths, a couple in their 40s who worked in the park her first year there. This would have been Jeannette Smith and her husband. After Enid Michael, she was the longest serving woman ranger at the park. She worked as a temporary park ranger each summer from 1926 through 1929. From 1930 through 1923 she was a park ranger (checker).

Yosemite’s “Flower Ranger”

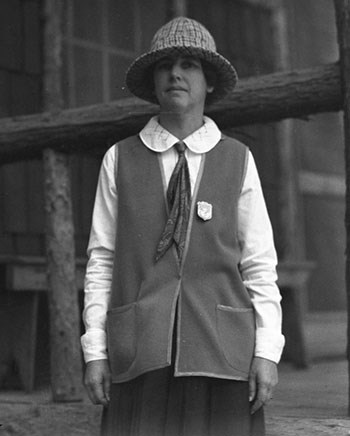

Having moved to Yosemite with her husband in 1919, Enid Michael, 36, earned mention in that year’s NPS director’s annual report for her volunteer work developing a flower exhibit. She was “in the right place at the right time” then to be hired as a temporary ranger in 1921. A newspaper article published that year described Michael as “the only women in Yosemite who wears the badge of a Park Ranger.”

She quickly became associated with displays of flowers and plants at the park. A 1922 newspaper article called her the “Flower Ranger of Yosemite.” She continued as a park ranger from June to August each summer from 1922 through 1924. In 1925 and 1926 her title was tweaked to “park ranger (nature guide)” before returning to park ranger in 1927. In these first seven years, her salary increased from $75 to $135 per month.

In 1923, Michael actively sought a year-round appointment as either a park naturalist or park botanist, writing letters and encouraging women’s clubs to campaign on her behalf. These efforts were not well received by the NPS or Dr. Harold Bryant, one of the founders of the Ranger Naturalist Service. Writing to Carl Russell in December 1923 about a permanent position for Michael, he opined, “I think this unwise at the present time.” In an apparent warning about her, he stated, “As you have been informed before, one of your greatest problems, and one which needs the greatest tact to solve, lies in this direction.” Michael, for her part, recalled that “Dr. Bryant was of the opinion that the Ranger Naturalist Service was for men and he did not approve of women taking part.”

Michael finally got a permanent "when actually employed" (WAE) appointment as a ranger-naturalist in 1931. The appointment was primarily to compensate her for some of the time she had been working for free each winter. However, the hours were very limited and it hardly constituted the year-round appointment she had been hoping for.

Michael's disagreements with her supervisor Park Naturalist Bert Harwell are well known. In 1933 and 1934 he gave her largely negative performance reviews. He evaluated her strengths as her knowledge of botany and ornithology. Her weakest science was geology. Her ability to lead tours was listed as “poor, expect special and very small groups." He felt that she had a "bad habit of talking down to groups” and “a shallow high-pitched voice which when raised so as to be heard by large audiences became a monotonous sing-song. Bed-time story effect as though always talking to kindergartners.” He reported that Michael "does not like people" and "shuns meeting the publice," but "has done excellent work pressing flowers for exhibit." Among other things, he also complained that she was never in uniform and gave little thought to her personal appearance.

In 1933 he rated he as fair. As their issues continued, he gave her a poor rating in 1934 and recommended she not be hired again, because she “has always been a source of irritation in Yosemite Naturalist staff. Poor health has aggravated her non-social nature and disposition. She has never worked well in any project requiring teamwork. For several years she has had responsibility of developing our museum garden project. She has never been able to develop a logical plan. I feel the only solution is that she be replaced in this naturalist position.”

As a result of Harwell's recommendation, she lost her permanent position in 1934. In approving her dismissal, the superintendent said that he wasn’t approving it because of what Harwell wrote, amazingly enough, but “for a consistent unwillingness to keep in step with, and be loyal to, the park naturalist. I value her knowledge and feeling for the park very highly, but this organization must be a unit, and individualities must be subordinate to the good of the service.”

Not everyone shared Harwell's opinions of Michael. Ruth Ashton Nelson, a fellow botanist, remembered Michael as “pleasant and very dedicated.” Others who knew her described her as someone who “didn’t let go” and who “had a waspish tongue that got the better of her from time to time.”

After losing her permanent WAE position in 1934, she was considered on a seasonal basis—and despite Harwell's complaints, the park kept hiring her. She also served as an instructor at the Yosemite Field School for many years. Her last season with the NPS was in 1942. It literally took a world war before they stopped hiring her.