Last updated: October 31, 2020

Article

A Conservative Union Parish: St. Paul's Church and the Civil War

A Conservative Union Parish:

St. Paul’s Church and the Civil War

Introductory Panel:

Far from Gettysburg or Vicksburg, graves of scores of Union soldiers dot the historic cemetery at St. Paul’s Church National Historic Site. These men fought in the blue uniforms but lived through the war between the North and the South. They returned to civilian life, raising families, pursuing occupations, struggling with post war adjustments and remaining active in veterans’ affairs before passing through natural causes in the late 19th or early 20th centuries. Fighting in the war for the Union was a cornerstone of their lives, and they claimed an enduring testament of their service -- veterans’ stones. Their experiences form a core of this exhibition, helping to commemorate the sesquicentennial of the Civil War.

The display also chronicles a parish and town wrestling with the questions that underlay the national conflict of 1861 – 1865. Like most Episcopal churches, St. Paul’s publicly expressed a conservative position on the divisive sectional issues of slavery that pushed the nation toward a break in the antebellum period. Part of the commercial nexus of metropolitan New York, the community shared the goal of sectional peace, which often meant removing slavery from the public discourse. Opposition to President Lincoln’s war policies included the allocation of thousands of dollars to help men avoid military service. But St. Paul’s was not a Copperhead neighborhood and ultimately supported the effort to preserve the Union.

Following the war, St. Paul’s emerged as ceremonial center of a post of the nation’s first national veterans’ organization, the Grand Army of the Republic. Sustaining memories of service and supporting comrades, hundreds of local Union veterans joined New York’s Farnsworth Post 170. On commemorative occasions, they paraded on the church grounds and the cemetery, honoring departed soldiers from the early 1880s through the 1920s. We invite you to explore the Civil War as experienced in this corner of the republic through these artifacts, photographs, documents, artwork, text, model and sound.

The exhibition was made possible by:

National Park Service/Department of the Interior

Gloria Jarecki

New York Council for the Humanities

Society of the National Shrine of the Bill of Rights

John and Jean Heins

Panel 1: The Church and the War

Protestant ministers were among the leaders of the Northern antislavery crusade in the decades before the Civil War, but the Episcopal clergy rarely got involved in the abolitionist movement. Emphasizing continuity in religious and moral affairs, Episcopalians, including the parish of St. Paul’s Church, avoided progressive reform campaigns. Additionally, with parishes in both the North and South, the Episcopal Church was leery of disrupting the denomination with an open discussion about slavery, especially considering the separations that such a dialogue created in other Protestant churches.

The St. Paul’s community’s response to the Civil War was also influenced by a conservative political stance on the controversial sectional issues. Good relations and open trade with all regions of the republic were crucial for metropolitan New York, the nation’s great mercantile emporium. With strong commercial and social ties to the South, New York’s most valuable export in 1860 was cotton; it was called “the most Southern city in the North.” The city and the surrounding communities, including the St. Paul’s vicinity, opposed Republican antislavery principles because they feared such radical appeals threatened the stability of the Union.

Like its neighbors, the town of Eastchester, which encompassed the parish of St. Paul’s, voted against the Republican candidate, Abraham Lincoln, in the Presidential elections of 1860 and 1864, and all local newspapers were Democratic.

While this conservative backdrop fashioned the community’s reaction to the great national conflict, St. Paul’s was not a Copperhead neighborhood. There’s no record of demonstrations in favor of the Confederacy or activities to disrupt the Union war effort. Following secession, which was considered treason, most people supported the effort to preserve the Union, while opposing emancipation and the war measures of the Lincoln government. Many parishioners volunteered for the Union army. Women met in the church to assemble care packages for soldiers at the front.

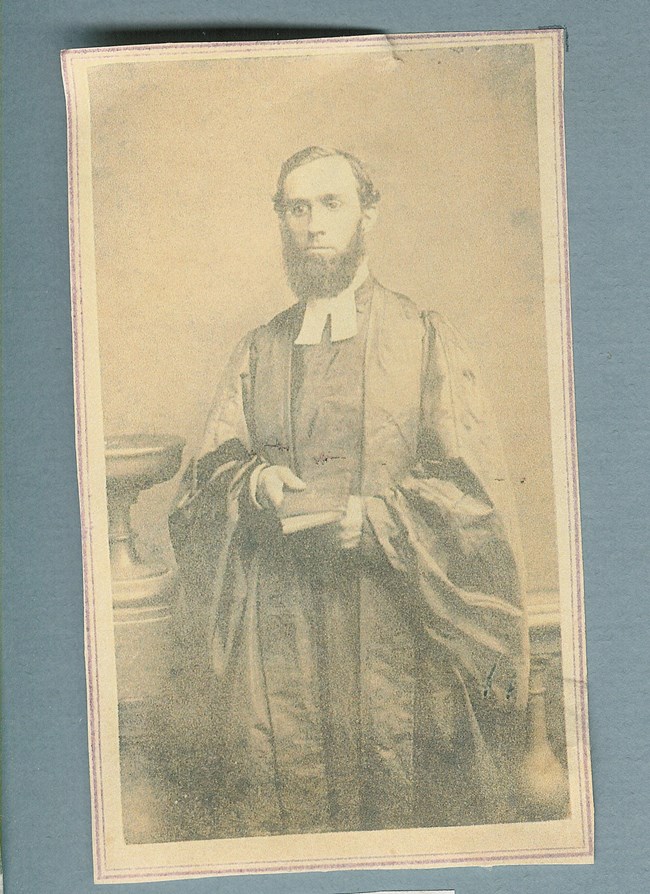

No rousing abolitionist sermons or strong war cries were expressed from the St. Paul’s pulpit, yet the church rector William T. Coffey sustained the military effort to preserve the nation on a more personal level. Community tradition recalls Rev. Coffey’s support for the Union, and private correspondence articulated his views, assuring one soldier at the front “I feel a deep interest in the cause in which you are engaged. I know of scarcely another so holy. Common gratitude, self interest and philanthropy demand the efforts at whatever the sacrifice to sustain our government.”

Panel 2: “300,000 more”: The 6th New York Heavy Artillery

The Union army recruitment drive of 1861 generated little enthusiasm in the St. Paul’s vicinity, an indication of the area’s conservative stance on the sectional disputes and a shortage of wealthy residents willing to raise and equip troops. The absence of a local enlistment drive forced men interested in serving to travel to New York City, where many regiments were gathered. A swift Northern victory would have precluded significant military participation by the young men of the area. But Southern victories in the Battles of the Seven Days in the early summer of 1862 created an urgent need for additional Northern soldiers, and President Lincoln issued a call for “300,000 more” to defend the Union and subdue the rebellion. That enlistment drive in August drove the imagination and patriotism of local residents, leading to a sizable number of enlistees.

Approximately 80 of them joined the 6th New York Heavy Artillery, which was recruited in Westchester, Rockland and Putnam Counties. Offering a distant mirror on the Union army and the area, these men ranged in age from 16 to 63, with an average of 25. Almost all of them were native born, and while a majority was farmers, economic changes in the area are suggested through the industrial trades listed on enlistment forms by several troops. “When the regiment was formed there were no bounties offered as an inducement to enlist and it is safe to say that patriotism is the only motive that brought this body together in defense of our country’s cornerstone, the constitution,” declared William Thiselton, a cobbler from the nearby, newly formed village of Mt. Vernon, who chronicled the regiment in his diary.

Deployed to protect the capital area, heavy artillery units were trained in the use of largesiege canon, and the 6th was stationed around Baltimore and Washington D.C., experiencing minimal conflict. That changed in the spring of 1864. General Ulysses S. Grant launched the Overland campaign in Virginia, attacking the Confederate army under General Robert E. Lee in an effort to conclude the war before the fall elections. Bolstering the Northern forces, the 6th New York and several additional heavy artillery regiments were reorganized as infantry units and joined the Army of the Potomac. Since they had suffered few casualties, the heavies, as they were often called, were the largest regiments in the blue lines.

Men from the St. Paul’s vicinity fought with the 6th in the subsequent campaigns until Confederate surrender in April 1865 -- the Wilderness, Spotsylvania, Cold Harbor, Cedar Creek, the Petersburg battles. The battle of Harris farm in Virginia, waged on May 19, 1864, was perhaps the unit’s greatest military achievement. General Grant was withdrawing his forces for a march around the eastern flank toward the North Anna River. General Richard Ewell, reconnoitering with experienced Confederate troops, stumbled into the heavy artillery brigade, which was guarding the Union supply line.

In its first brush with the realities of combat, the 6th engaged in a defensive operation, fighting shoulder to shoulder in parade ground formation. But unlike other troops in initial battle, they held their ground, trading rifle rounds with the much more experienced Southern troops for two hours, when “the onset though desperate was repulsed, the enemy’s line being broken by the resolute courage of our men,” Sergeant Thiselton proudly recalled. General Gordon Meade commended the regiment “for their gallant conduct in this affair and classing us with the veterans of the Army of the Potomac.”

Panel 3: Experiences and Consequences of War

In the years following the war, dozens of former Union soldiers moved to the growing communities of southern Westchester County. Many of these veterans were interred in the St. Paul’s church yard. Their stories show that the Civil War was a defining experience for those who fought as well as the families to whom they returned.

For George C. Carter, the Civil War meant freedom and a greater sense of personal achievement. At the war’s outset, Carter, 19 years old, was enslaved on a plantation in northern Virginia, scene of early Civil War battles. He escaped and reached Fortress Monroe, a refugee camp that provided protection to thousands of former slaves, including Rosa Quales, who became Carter’s wife. With the creation of the United States Colored Troops in 1863, he journeyed to Hartford, Connecticut and enrolled in Company C., 10th USCT. Private Carter campaigned in Virginia, helped capture Fort Powhattan and secure Richmond, the Confederate capital, which fell in early April 1865. Honorably discharged, he was among the bold CT veterans who moved to the North in search of better life. Along with his wife and four children, Carter lived first in Babylon, Long Island before moving to Mt. Vernon in the early 1880s. Carter found work as a schools janitor and a gardener on a large estate in Eastchester, passing in 1902, age 60. His grave is marked with a veterans stone.

Daniel Lawlor’s service as a combat solider with the 69th New York Infantry lasted only a few weeks before he was captured by the Confederate in fighting around the Weldon Railroad in August 1864. The Irish-born New Yorker was transported via rail about 200 miles from Virginia to a prisoner of war camp in Salisbury, North Carolina, entering the twilight zone of Civil War prisoners at the most perilous point of the war to be a captive. Prisoner exchanges, or cartels, conducted in the early years of the conflict had been suspended. Population at a facility designed for perhaps 2,500 captives reached 10,000, and rapidly deteriorating conditions led to the death of approximately 5,000 troops. One of the fortunate soldiers who survived, Private Lawlor gained parole in mid February 1865 when exchanges resumed. His last few months of Union service included a thirty-day furlough in New York, a welcome period of reunion with his family and recuperation, given his emaciated condition upon release from Salisbury. In the 1870s, the Lawlors relocated to the growing village of Mt. Vernon where Daniel enjoyed a lengthy post war civilian life through 1916, when he was buried in the historic cemetery at St. Paul’s Church.

Matthew J. Graham never really recovered from wounds received at the climax of the deadliest day of the Civil War, stretching out a painful existence in New York for more than 40 years, but managing to write a classic history of his regiment, the 9th New York (Hawkins Zouaves) Volunteer Infantry. A lieutenant, Graham suffered a gunshot wound at a critical juncture of the Battle of Antietam, September 17, 1862, requiring the amputation of his right leg four inches above the knee. The almost constant pain from his leg made the post war years extremely difficult. His marriage collapsed, and he had trouble finding employment, but memories of the war and pride in service sustained him. Graham was an officer in a Grand Army of the Republic veterans post and regularly attended reunions of the 9th Zouaves. His fellow veterans selected him to author the regimental history, an honor reflecting his martial contribution and literary ability. Produced in 1900 and written over several years by an aging veteran fraught with “intense agony,” it is a remarkable memoir of men, war, suffering, heroism, sacrifice and reconciliation. Graham lacked a religious or family connection to St. Paul’s, but other veterans of the 9th who lived in the community arranged a final resting place for their comrade in the church cemetery.

“I leaped from the top of the orchestra railing in front of me upon the stage, and, announcing myself as an army surgeon, was immediately lifted up to the President’s box by several gentlemen who had collected beneath,” Dr. Charles S. Taft recalled. Moments after the shooting of Abraham Lincoln by John Wilkes Booth, the Civil War experience of the Union army surgeon Dr. Taft took a tragic and dramatic turn, April 14, 1865, at Ford’s Theatre in Washington D.C. He helped to diagnose the wound, declared to be mortal, and assisted in carrying Mr. Lincoln to a boardinghouse across the street. Through the night and vigil, in a small room filled with cabinet officers, Lincoln’s family and physicians, Dr. Taft assisted with various, almost hopeless medical procedures. A famous painting of the deathbed scene shows Dr. Taft holding the President’s head. Often linked to that historic event, Dr. Taft retired to Mt. Vernon in the 1890s, and was buried at St. Paul’s in 1900.

Captivated by the Civil War combat prowess of George A. Custer, Frederick Whittaker wrote the first and perhaps most controversial biography about the infamous cavalry commander who was killed at the Battle of the Little Big Horn in June 1876. Born in England, Whittaker’s family moved to Brooklyn in the 1850s. In 1861, the imaginative young Frederick joined the 6th New York Cavalry. Eventually rising to captain, Whittaker fought with distinction in some of the war’s major engagements, including Gettysburg. He also had the opportunity to witness Custer’s battlefield daring and skill. After the war, Whittaker moved to Mt. Vernon and joined the St. Paul’s congregation, where he worshipped, eventually married and baptized his daughters. Whittaker pursued a successful career writing highly adventurous dime novels, and through his work as an author met and befriended Custer, his model of a romantic hero. Custer’s decisive defeat at the hands of an Indian force at Little Bighorn led Whittaker to publish A Complete Life of General George A. Custer. He created a lofty image of his deceased friend as a fearless and brilliant soldier, and “a great man, one of the few really great men that America has produced.” A spiritualist, Whittaker died of an accidental, self inflicted gunshot wound in 1889, and was interred at St. Paul’s.

Hiram Slagle’s post war experience illustrates the debilitating effect of the Civil War on many veterans. A cobbler from Sing Sing (today’s Ossining), Slagle served two years with the 17th New York Infantry, the Westchester Chasseurs. He was captured at the second Battle of Manassas, paroled and exchanged. In May 1863, he was wounded in the hand at Chancellorsville. After receiving an honorable discharge his life spiraled into disarray, for reasons not entirely clear. Slagle left his family and led a meager existence on his own. His wife died, and the children were transported west on one of the notorious orphan trains of the 19th century, where they were adopted by farm families. Slagle survived marginally for several years in Mt. Vernon, basically homeless, earning wages by selling clams or mushrooms. The end came on a wintry night, January 14, 1901. Found unconscious on South Fourth Avenue after tumbling down a flight of stairs, Slagle was transported via horse-drawn ambulance to Mt. Vernon Hospital, but he never regained consciousness. A search of his clothing revealed his Union army discharge papers, a proud memory he preserved despite the downturn in his life. An indigent, Slagle was interred at city expense in an unmarked grave in the cemetery, although more than a century later a granite veterans’ stone was placed upon his grave by St. Paul’s staff.

Panel 4: 1864: The limits of Patriotism

In the spring and summer of 1864, heavy casualties in the Virginia Overland Campaign and the perception that the military drive was stalled led to diminished support in the St. Paul’s community for the Union war effort. The clearest reflection of this sentiment was assistance provided by the town to young men called for the draft who chose not to serve. The draft had been controversial since its inception, sparking the infamous New York City riots of July 1863. While Eastchester never experienced that level of lawless insurrection, the community strongly opposed President Lincoln’s call for more troops in 1864. This mirrored a reluctance to supply additional men in many Northern communities which were Democratic and registered a further expression of the inconsistent support for the war that characterized the St. Paul’s area.

The town government created a committee to retain the services of substitutes for local draftees who declined to serve. Public support for these draftees indicated a lack of confidence in the Lincoln war policies, and sympathy for men of modest means who did not want to fight. Small towns like Eastchester also feared losing a large percentage of their able-bodied men to the army. They were willing to expend public funds to retain their residents on the home front as farmers and laborers who sustained the local economy.

The ability to hire a man to serve in the army in place of a draftee was incorporated into the enrollment act, stipulating a payment of $300. In practice, it was a market-driven enterprise, and the cost, or fee paid to the substitute, could vary widely depending on the location and timing, possibly reaching $1,500. Even the usual range of $250 to $350 was an enormous sum for most working men, equal to a year’s wages. Though abuses of the system were widespread -- with substitutes accepting the fee and quickly deserting -- the practice appealed to many capable men who for various reasons had difficulties entering the army through standard means.

One member of the town committee was Judge Joseph D. Fay, a parishioner who is buried at St. Paul’s. Judge Fay’s panel made several visits to the heavily populated neighborhoods of lower Manhattan, location of surpluses of available young men. The town obtained 13 substitutes at $285 each and two substitutes at $300 each. Eastchester had previously paid commutation fees of $300 for each of five draftees for whom no substitute could be found. This total public expenditure of $5,805 would be about $80,000 in today’s money, a sizable figure for a small town.

Panel 5: Memories of War: The Grand Army of the Republic

The Civil War experience did not end when the shooting stopped in 1865, and no organization did more to sustain the memory of the conflict than the Grand Army of the Republic. The GAR, as it was often called, was the largest Union veterans’ group. Enrollment peaked at 490,000 members in 1890, and the order’s prestige and influence were enhanced through the election of five members to the White House.

Located in Mt. Vernon, the Farnsworth Post New York 170 of the GAR was founded in 1880. Fifteen years after Union victory, this was a time of great expansion for the veterans group -- memories of the horrors of the war had faded, but recollections of shared commitment and sacrifice remained strong. Enlisting 175 members, the Farnsworth post was involved in a myriad of fraternal and charitable activities among members -- free medical care and medicine, cash relief payments and services, burial costs, financial assistance to widows and orphans. Educational and patriotic programs disseminated information on the significance of the war and the role of the Union soldiers. A secret initiation rite, modeled on the Masons, reinforced a special bond among the former soldiers.

Representing Union veterans, the GAR’s public activities were closely aligned with the Republicans, the party of Lincoln and Grant. It was difficult to secure the nomination for local offices without GAR endorsement, leading to the nickname “Generally All Republicans.” This affiliation with the nation’s dominant party, combined with excellent organizing abilities and widespread gratitude toward the Union soldiers, produced the first successful national lobby. The GAR played a major role in passage of the Dependant Pension Act of 1890, which created monthly pensions for thousands of veterans and widows, including many people interred at St. Paul’s. Dispensing $1 billion by 1907, these payments were the largest expenditure in the Federal budget.

Christianity underscored the Farnsworth ritual. Chairs in the lodge room were arranged in the form of a cross. A Bible rested on an altar at the center of the lodge; prayers and references to Jesus were included in the weekly gatherings. These religious emphases appealed to Stephen Hunt, whose spiritual and social life was anchored at St. Paul’s, directing the Sunday school for 40 years and serving on the vestry board for 58 years. A carpenter by trade, Hunt fought with the 8th New York Heavy Artillery, experiencing heavy combat in the Virginia fighting of 1864-5. Hunt’s religious faith merged with pride in his military service, and it’s not surprising that he volunteered as chaplain of Farnsworth Post 170. Reflecting the political connection of the order, Hunt also served as a local Republican official, hosting paper ballot primaries in his home of South 4th Avenue, less than a mile from St. Paul’s. His part in the Union army’s victory over the South helped sustain the former corporal in his twilight years, receiving a pension beginning in 1890, and obtaining his last monthly payment of $20 (about $500 in today’s money), days before passing August 10, 1910, at age 81, and interment at St. Paul’s.

Memorial Day exercises at St. Paul’s symbolized the bond between the living Farnsworth men and the dead Union veterans. With eighteen members of the post buried in the five-acre cemetery, the church functioned as the group’s spiritual fulcrum. The unit’s history recalls that “the muffled drum beat on Memorial Day, is heard but faintly, though with reverence, as the members of the Farnsworth Post wend their way once more to the graves of comrades who have gone before.”