Part of a series of articles titled The Midden - Great Basin National Park: Vol. 22, No. 2, Winter 2022.

Article

A Closer Look at Nevada Primrose

This article was originally published in The Midden – Great Basin National Park: Vol. 22, No. 2, Winter 2022.

Austin Koontz

By Austin Koontz, Researcher

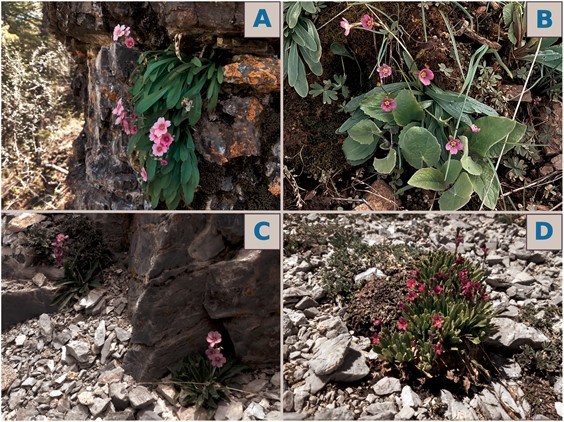

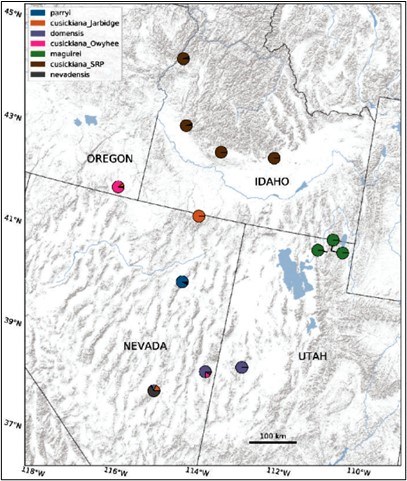

At the summit of Mt. Washington grows a rare plant with a unique backstory. Primula cusickiana var. nevadensis, the Nevada Primrose, is a perennial plant with showy purple petals (Panel D in image to the right), and was first described as its own species in 1967 by Noel Holmgren. It is part of the Primula cusickiana species complex: a group of related plants with similar morphologies found throughout the Great Basin. The other varieties in the complex are:- P. cusickiana var. maguirei, in the Bear River Range of Utah (A);

- P. cusickiana var. cusickiana, across the Snake River Plain in Idaho but with a population also in Jarbidge, Nevada (B)

- P. cusickiana var. domensis, in the House Range in Utah, just across the border from Great Basin National Park (C)

NPS

At the end of the Pleistocene 11,700 years ago, the Great Basin was a cool, relatively wet area featuring large lakes, such as the ancient Lake Lahontan and Lake Bonneville. At this time, the ancestor of Primula cusickiana was likely prevalent throughout the region. Over the course of the next 10,000 years (the Holocene), the Great Basin became hotter and drier. Mountaintops, however, continued to provide the cool conditions many organisms were used to; as the climate changed, these organisms retreated to these mountainous regions, which scientists call refugia. Primula was one of these organisms: as it retreated towards higher elevations to follow the cool, moist soils it prefers, its populations became fragmented. This fragmentation led to populations becoming more and more genetically unique, leading to the strong genetic divisions we see between populations today.

Our research also shined a light on the unique nevadensis population on Mt. Washington. Our research suggests that this population of nevadensis is a hybrid between the domensis population (to the east in the House Range) and another nevadensis population further south (in the Grant Range). More needs to be done to characterize these two populations, but our work suggests that the Mt. Washington population (and indeed all populations) is very unique!

I hope this work is built upon and can lead to the protection of these rare and unique plants! Interested readers can find out more about this work in the article here, published in Systematic Botany.

Last updated: February 5, 2024