Last updated: February 22, 2023

Article

South Central Pennsylvanians in the 54th Massachusetts Infantry

NPS Photo/Boston African American National Historic Site

"All the Boys in our Place Were Ready

Hardly Anyone Who Could Carry A Musket Stayed Home”

I was eleven years old when the movie Glory first hit the theaters in late 1989.

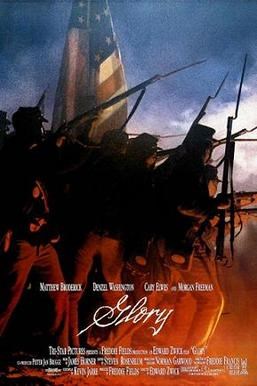

Already at that young age I had a long-held and deep fascination with the American Civil War. Because of this and despite the movie’s 'R' rating, my parents took me to see Glory when it first debuted, and then several more times after that. In fact, during its first initial theatrical run, my parents took me to see it seven different times! And just last summer, when the movie was re-released in observance of its thirtieth anniversary, I caught it twice more. In my personal estimation, Glory quite simply was and still is one of the very best Civil War movies ever made; it is raw and realistic, and tells an important and inspiring story, one that upon its initial release went largely under told in Civil War history and memory. The soundtrack, too, composed by the late James Horner, is beautifully haunting and emotionally stirring, making it the film’s perfect musical accompaniment.

Directed by Edward Zwick and featuring an exceptional, star-studded cast, Glory tells the story—or at least, a part of the story—of the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry and its first commanding officer, Colonel Robert Gould Shaw, from the regiment’s organization to its bloody and forlorn assault upon Battery Wagner on Morris Island, Charleston, South Carolina, on July 18, 1863. The movie focused on six main characters, although only one of these six was based on an actual person, that being Colonel Shaw portrayed by Matthew Broderick. The other main actors in Glory portrayed entirely fictitious soldiers: Cary Elwes played Major Cabot Forbes; Denzell Washington, Private Silas Tripp; Morgan Freeman, Sergeant-Major John Rawlins; Andre Braugher, Corporal Thomas Searles; while Jihmi Kennedy portrayed Private Jupiter Sharts. Each did a powerful job in portraying these characters, with Washington even earning an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor for his portrayal of Private Tripp.

TriStar Pictures

Glory helped to bring much needed attention to what was then a long neglected, or at least, largely under told part of Civil War history. Though it focused on one regiment in particular—the 54th Massachusetts Infantry—the movie brought wide public attention to and helped shine a light on the service of the nearly 200,000 African American men who served in the uniform of the United States during the final two years of the conflict, a number that represented a full 10% of the Union’s entire fighting force. Of this number, an estimated 30,000 gave their lives so that this nation might live.

But for all Glory did in bringing this story to light—and for all it did in furthering my own interest in America’s Civil War—the movie is not without its criticisms and not without its inaccuracies, some of them minor or trivial, some significant. To begin, the 54th Massachusetts—the first all-Black volunteer regiment to be raised and organized in the North, east of the Mississippi River—was organized in the late winter and early spring of 1863 and not in the fall of 1862, as is depicted in the film. While a seemingly minor point, this actually does a disservice to the real soldiers of the 54th, for, as historian Martin Blatt pointed out, the real regiment had only a very short time to train before being sent off to war and within this short amount of time they became one of the Union’s best-trained and disciplined volunteer regiments, well-prepared for what lay ahead of them on campaign and in battle. Also, and opposed to what is emphasized in the film, those who volunteered into the ranks of the 54th and who subsequently passed the rigorous physical examination were provided with shoes and a uniform the day they were mustered into service, the regiment being very liberally supported by the State of Massachusetts and other benefactors. Further, Governor John Andrew of Massachusetts offered Shaw command of the regiment by way of a letter first sent to Shaw’s father and not at a social gathering in the presence of Frederick Douglass, as is depicted in the film. For the final, climatic scenes of the movie, depicting the doomed assault on Battery Wagner, the 54th is shown attacking from north-to-south, with the Atlantic Ocean to the left of the regiment, when, in fact, the actual assault was up the beach, from south-to-north, with the Atlantic to the soldiers’ right and the sun setting to their left. Finally, even though the closing credits of the movie state that Battery Wagner was “never taken,” it was, in fact, abandoned by Confederate forces in early September 1863, about seven weeks after the 54th’s doomed assault. It was immediately occupied by Federal troops and held in Union hands for the duration of the conflict. While these may be minor flaws, a more substantial criticism is the very limited screen time given to the abolitionist Douglass, who played such an important role in lobbying for Black soldiers and in recruiting volunteer soldiers for the 54th Massachusetts.[1]

Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society

Perhaps the movie’s most significant flaw or shortcoming, however, was in its depiction of the actual soldiers of the 54th Massachusetts. As noted, every Black soldier or character in the movie is entirely fictionalized. Missing from the movie ranks of the 54th Massachusetts were the regiment’s real-life heroes, soldiers such as William Carney, Lewis Douglass, and Stephen Swails. In the words of Martin Blatt, the movie presented a “fictionalized ensemble of Black soldiers.” Its real soldiers were thus invisible. And because three of the four main soldiers depicted in the movie—Sgt. Rawlins, and Privates Tripp and Sharts—had once been enslaved, the movie gives the impression that the 54th Massachusetts was composed primarily of southern-born former slaves when, in fact, the regiment was composed mostly of free-born African American men from throughout the Northern states.[2] While these are valid criticisms, it must also be remembered that Glory was not intended to be a pure documentary, and instead sought to tell the larger story of the role of African American soldiers in the Civil War through the story of the 54th Massachusetts, and in this they very much succeeded.[3]

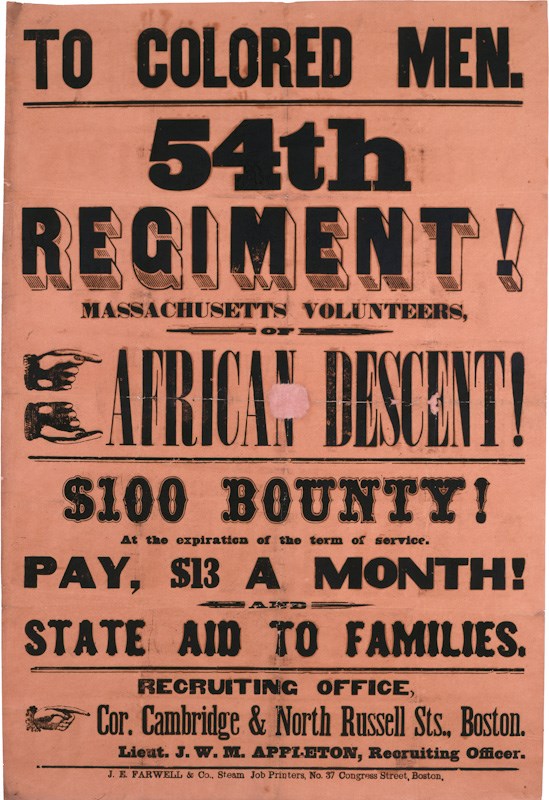

So, then, who were the real soldiers of the 54th Massachusetts Infantry? Many are surprised to learn that the ranks of this famed and fabled regiment were composed of men from nearly every Northern and Southern state, and that only a small percentage of its soldiers were actually from Massachusetts. In fact, when first organized in early 1863, there were more men from Pennsylvania in the 54th Massachusetts than from any other state, including Massachusetts. This was because the African American population of Massachusetts in the 1860s was simply not large enough to field an entire regiment on its own. Indeed, in all of Massachusetts in 1860, there were only 1,973 Black men of fighting age (18-45). When the regiment departed Boston for the seat of war on May 28, 1863, it numbered 1,044 officers and men. Of this number, only 133 (just 13%) called Massachusetts home. 155 men came from Ohio, while 183 were recruited in New York. Well over 300, the most from any one state, came from Pennsylvania.[4] More than half who enlisted from Pennsylvania were recruited from Philadelphia, West Chester, Lancaster, and their surrounding areas. However, a good number came from the rural agricultural townships and small market towns of south-central Pennsylvania, from places like Mercersburg, Columbia, Shippensburg, and Carlisle. Two were born in Gettysburg.

For the purposes of this article, I am considering south-central Pennsylvania as being anywhere within a forty-five-mile radius west, north, and east of Gettysburg, which sits squarely in the central and southern part of the Commonwealth, just a few miles north of the Mason-Dixon Line. This geographic span includes places like Harrisburg, Carlisle, and Middletown to the north; Columbia, York, and Hanover to the east; and Shippensburg, Chambersburg, and Mercersburg to the west. It is an area that encompasses six of Pennsylvania’s sixty-six counties, including all of Adams, Cumberland, Franklin, and York Counties, most of Dauphin and the extreme western edge of Lancaster County, where Columbia is located, directly on the banks of the Susquehanna River. Examining the regimental record books as well as the roster contained in Captain Luis Emilio’s regimental history, A Brave Black Regiment, at least 124 soldiers of the 54th Massachusetts were either born in, resided in, or enlisted from this region of south-central Pennsylvania, which is the equivalent of more than one entire company of soldiers.[5]

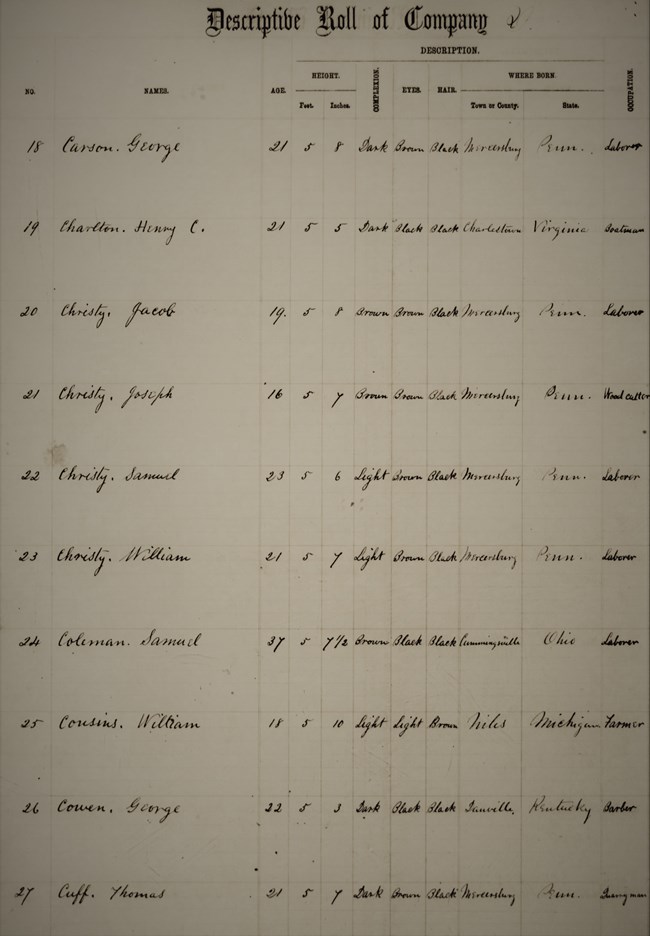

A statistical snapshot of these men is instructive, for it helps paint a picture and tell the larger story of the real soldiers of the 54th Massachusetts Infantry. To begin, these were young men. The average age of these 124 soldiers was 23.6 years, which is younger than the average of all Civil War soldiers, which was 25.8 years. Of the 124 soldiers from south-central Pennsylvania, 96—or 77%--were between the ages of 16 and 25. Only 28 men were age 26 or older. Among the oldest was Edward Parks of Company I, a 43-year-old hostler from Carlisle, Pennsylvania. Henry B. Marshall of Company C, a cook from Harrisburg, was 45 years old, and, oldest of all, was Thomas E. Brown of Company E, a 48-year-old laborer from Middletown. On the other end of the age spectrum were the youngest soldiers to come from south-central Pennsylvania: Privates James Rideout of Company I and Franklin Green of Company D were each seventeen years old, while Joseph Christy of Company I—one of the four fighting Christy Brothers to serve in the regiment—was just sixteen years old when he enlisted to fight on April 22, 1863.

As might be expected, because so many of these men were young, most were single or unmarried at the time of their enlistment. In fact, only 32 of the 124 south-central Pennsylvanians in the ranks of the 54th Massachusetts were married when they entered the army, about 25%.

National Archives and Records Administration

Because educational, vocational, and economic opportunities were not nearly as readily available to African American men in the North in the pre-war years as they were to white men, it is no surprise that 62, exactly half of the 124 men under study, were employed as day laborers. Among the Union’s white soldiers, only 10% were so employed when they marched off to war. Most white Union soldiers—about 50%--were farmers or farm laborers. Among the 124 south-central Pennsylvanians in the 54th Massachusetts, only 32, or about 25%, identified their occupation as either farmer of farm laborer. There were a small number of skilled tradesmen among the 124, including two blacksmiths, two brickmakers, two quarrymen, two barbers, a shoemaker, a forgeman, a woodcutter, a carpenter, a butcher, a baker, and a mason. There were also a “stablehand,” a coachman, a clerk, and two boatmen.

Most of the 124 men from south-central Pennsylvania who served in the 54th claimed to have been born in the free state of Pennsylvania. Only 20 identified another state as their place of birth—one from New York, one in Illinois, and the rest from southern slave states: one was born in North Carolina, seven in Virginia, and ten in Maryland—however, it is also not known for certain whether these men—or others in the regiment from south-central Pennsylvania—were born into slavery. Records indicate that at least one man was. Hezekiah Allen McPherson was born in Prince George’s County and escaped to freedom, settling in Harrisburg and changing his name of John McPherson. Surviving the war, John McPherson today lies at rest in Arlington National Cemetery.[6]

There were no doubt others among these 124 who were born into slavery and perhaps more who were born in the South. With the infamous Fugitive Slave Act and Confederate proclamations and policies about capturing former slaves in uniform, along with a host of other factors, it is easy to understand why some would choose not to disclose their true place or status upon birth to army officials upon entering the ranks, especially if they had fled from slavery. This seems to have been a common occurrence in the 54th Massachusetts. Of the 1,300 men who served in the regiment from 1863 to 1865, the regimental records identify only thirty as having been born into slavery. And utilizing these records, Captain Emilio wrote in his regimental history that “only a small proportion” of the soldiers in all of the 54th had once been enslaved. However, in his own study and analysis of the regiment, historian Edwin Redkey pointed out that 322 members of the 54th, or 24.75% of the entire regiment, were born in southern slave states. It is hard to believe that only 30 of these 322 men born in slave states were born into slavery. The number of former slaves in the ranks of the 54th must surely had been much higher.[7]

For those men in the regiment who were either born in, resided in, or enlisted from south-central Pennsylvania, from where did they exactly come? Of the 124, a full one-quarter of them—32—claimed the small Franklin County town of Mercersburg as their home. Founded in 1780, Mercersburg—also the birthplace of James Buchanan, who preceded Abraham Lincoln in the White House—was a very small town. By 1860, the total population numbered only 900 men, women, and children, and, of this number, only 89 were identified as Black. While some of the 54th’s soldiers from south-central Pennsylvania may have come from Mercersburg-proper, most hailed from the area’s surrounding townships and rural farmlands. Many likely came from a thriving African American settlement located two miles west of Mercersburg known locally as “Little Africa,” which was home to more than 400 Black men, women, and children in the years before the war. Not surprisingly, this area of south-central Pennsylvania, being located so close to Maryland and the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia was a heavily traveled area along the Underground Railroad and many of the African Americans residents of “Little Africa” were either once enslaved or were the children of those who had previously and successfully achieved freedom. There they sought safe haven as well as the protection of a large community, composed also of free-born Pennsylvanians. Still, the Black residents of “Little Africa” and of all of south-central Pennsylvania remained ever wary and watchful for white Fugitive Slave Patrols and “slave catchers” from the South and from within neighboring communities. In total, 88 African American men from around Mercersburg and from “Little Africa” served in the Union army, 32 of them in the 54th Massachusetts.[8]

From the area around Mercersburg came the Christy brothers—Jacob, Joseph, Samuel, and William, the sons of Jacob and Catherine Christy—who served side-by-side in the ranks of Company I, 54th Massachusetts. Of the four fighting Christy brothers, two were destined to be seriously wounded in combat, while a third died in enemy hands after falling wounded at the Battle of Olustee. There was another set of four brothers who also served from the area around Mercersburg. They were the Krunkleton Brothers (sometimes spelled Crunkleton). Cyrus, James, William, and Wesley Krunkleton—all farmers—were mustered into service on the same date—May 6, 1863—becoming privates in Company K, 54th Massachusetts. Another brother, Henry, fought in the 54th’s sister regiment, the all-Black 55th Massachusetts Infantry. Like the Christy family, the Krunkletons also paid a heavy price. Two of the brothers were wounded in combat but survived and returned home; the other two did not.

Most of the 54th’s soldiers from Mercersburg and its surrounding area were mustered into service in either late April or early May 1863, having traveled to Camp Meigs, in Readville, Massachusetts, where the regiment was being trained and organized. In late May, the 54th departed Massachusetts and sailed to the coast of South Carolina. The men of the regiment from Mercersburg and all of south-central Pennsylvania were thus many hundreds of miles away from their homes and families when in late June 1863 soldiers of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia passed directly through their home area on the invasion that would ultimately culminate at the Battle of Gettysburg. Making their way north, Robert E. Lee’s men captured and kidnapped Black women, children, and men from southern Pennsylvania, bounding them by rope, placing them in wagons, and taking them south to be sold into slavery. This was especially true in and around Mercersburg. The Reverend Philip Schaaf recorded in his diary that “public and private houses were ransacked; horses, cows, sheep, and provisions stolen day by day without mercy; negroes captured and carried back into slavery (even those I know to have been born and raised on free soil).” It was, declared Schaaf, “a regular slave hunt” in Mercersburg, which presented the “worst spectacle” he saw during the course of the war. Thomas Creigh, also of Mercersburg, echoed Schaaf’s description of events, writing about one especially “terrible day” when Confederate “guerillas” passed several times through town with “several of our colored persons with them, to be sold into slavery.” When they finally left town that day, said Creigh, they carried with them “about a dozen colored persons, mostly contrabands, women and children. . . .Some of them were bound with ropes, and the children were mounted in front or behind the rebels on their horses.” One cannot know for certain, but there is a more than probable chance that among those so brutally hunted down, kidnapped, and sold into slavery while Lee’s Confederates operated in Pennsylvania were family members and friends of those 124 men who were serving in the 54th from south-central Pennsylvania, especially those who called Mercersburg home.[9]

National Archives and Records Administration

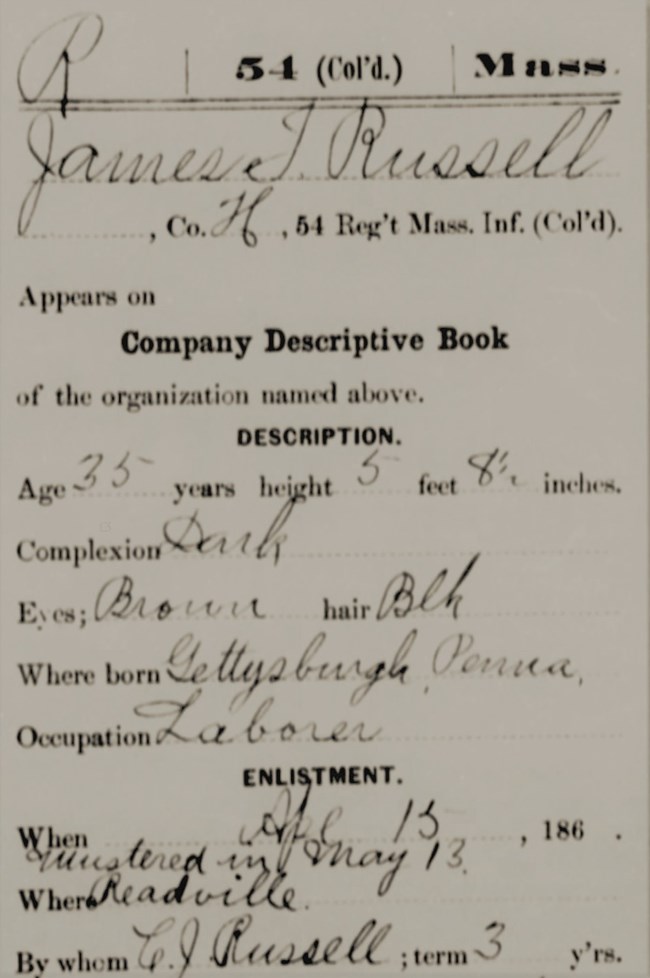

While one-quarter of the south-central Pennsylvanians in the 54th Massachusetts hailed from around Mercersburg, eighteen came from Carlisle, another eighteen from Harrisburg, nine from Middletown, and at least nine from Columbia, located on the eastern bank of the Susquehanna River. Eight men claimed “Franklin County” as either their place of birth or residence, with an additional nine men from Chambersburg and five from Shippensburg. Four soldiers had connections to either Adams County or to Gettysburg itself. Andrew Meads, the 21-year-old son of Henry and Julia Meads, was born in Adams County, though resided in and enlisted from Chambersburg. Stewart Wesley Woods, age 27, was also from Adams County, residing in the small community of Heidlersburg. Born in Gettysburg were James T. Russell and B. Harvey Williams, though eighteen-year-old Williams was residing in Chester County, Pennsylvania, when he enlisted to serve in the 54th Massachusetts. Other soldiers came from places such as Hanover, Wrightsville, Fayetteville, and Marietta.

But no matter their age, their occupations, their place of residence, or their motivations, these men from south-central Pennsylvania answered the call. Bidding farewell to their families and friends, they traveled first by carriage and by foot, and then by rail to Camp Meigs in Readville, Massachusetts, where the 54th was being organized and trained.

The 54th Massachusetts came into existence on January 26, 1863. This was the date when Governor John Andrew, after much lobbying, finally received authorization from the War Department to raise and equip a regiment of Black soldiers. By this time there had already been a number of all-Black regiments raised and already in Federal service, specifically the 1st Kansas Colored Regiment, the Louisiana Native Guard, and the 1st and 2nd South Carolina Colored Infantry. But Andrew’s regiment, which would become the 54th Massachusetts, was the first regiment of Black volunteer soldiers to be raised in the Northern states, east of the Mississippi River. Although composed of Black soldiers, the War Department ruled that the regiment’s commissioned officers must be white and so, upon his return from Washington to Boston, Governor Andrew reached out to a number of white officers with anti-slavery and abolitionist sentiments who were then already serving in other Massachusetts regiments and who thus had experience with volunteers in camp and on the battlefield. This included Robert Gould Shaw and Edward “Ned” Hallowell, the sons of ardent abolitionists. After first declining the command, Shaw, who in the winter of 1863 was a captain in the 2nd Massachusetts, accepted Andrew’s request to command the regiment; Hallowell, who was lieutenant in the 20th Massachusetts, also accepted Andrew’s offer and became the 54th’s second-in-command. Hallowell took command of the regiment following Shaw’s death at Battery Wagner and led it until the end of the war.[10]

Other officers appointed by Governor Andrew opened recruiting offices in Massachusetts, including one in Boston, one in New Bedford, and one in Springfield. However, because of the small number of African American men of fighting age in Massachusetts, strenuous recruiting efforts had to take place throughout the North. And so, on February 15, 1863, Governor Andrew established a committee of ten men—each committed abolitionists and including Robert Gould Shaw’s father, Francis—to superintend the raising of volunteers. This committee soon raised $5,000 to aid the recruiting efforts. A call for volunteers was published and reprinted in newspapers throughout the North. In addition, agents traveled throughout the North to actively recruit. Some of the most notable recruiting agents for the 54th were abolitionists George Stearns, Frederick Douglass, and Dr. Martin Delany. Major Ned Hallowell traveled to his native Philadelphia where he helped to recruit volunteers from in and around the city.[11] There were other members of the regiment who also embarked on recruiting duty, but it is not certain who made the long journey to south central Pennsylvania. The only hint comes from an article in the May 24, 1863 edition of the Mercersburg Journal: “A colored recruiting sergeant made an effort in this community last week among the colored people, and succeeded in enlisting about twenty able-bodied men some of whom on Monday morning were taken to Harrisburg and shipped to Boston to fill up the Massachusetts colored regiments. Our colored men are quite in earnest about the matter, and propose to increase the number to seventy-five or a hundred.”[12] Sergeant Henry Steward, of Company E, 54th Massachusetts, from Adrian, Michigan, was an active recruiter for the regiment; unfortunately, it is not at this time known for certain whether it was he whom the newspaper identified as the “colored recruiting sergeant” in Mercersburg.

While some of the volunteers who came from south-central Pennsylvania may have responded directly to the calls of a recruiter, many others may have also responded directly to the many reports and to the appeals printed in the newspapers. Newspapers throughout south-central Pennsylvania reported on the widespread volunteerism among the area’s African American men. One of the earliest reports was printed on March 25, 1863, in the Lancaster Examiner: “Recruits for the 54th Colored Massachusetts Volunteers—Quite a number of colored men in this vicinity are enlisting in this regiment. . . .the men who left Columbia were good material, and men whose labor will be missed in the Spring when the lumber season opens.” On April 24, the Carlisle Weekly Herald reported that “Within the last ten days at least, one hundred negro soldiers have been enlisted in this County, for a Black regiment now being raised in Massachusetts.” The Mercersburg Journal of April 24, 1863, included a brief note that “One day this week about fifty Negro Soldiers left Carlisle for Philadelphia, to join a Black Regiment now organizing for the service,” while the Greencastle Pilot on May 5, 1863, reported that “about twenty-five negro soldiers left Chambersburg for a Black regiment being raised in Massachusetts.”

The number of men arriving at Camp Meigs from Pennsylvanian quickly outnumbered those who were enlisting from Massachusetts, much to the embarrassment of some of the proud Bay State men in camp, including Corporal James Henry Gooding of New Bedford, who served in Company C. In an April 18 letter to the editor of the New Bedford Mercury, Gooding called upon African American men from Massachusetts to “emulate the men of Pennsylvania, who have left their homes in numbers to shame the colored men of the ‘Old Bay State,’ and ‘Cradle of Liberty.’”[13]

Most of the south-central Pennsylvanians who served in the 54th Massachusetts served in the ranks of Company I and Company K, the final two companies of the regiment to the organized. The soldiers of these two companies arrived at Camp Meigs and were mustered into service in late April and early May 1863, and were there, training, for less than one month before orders arrived for the 54th Massachusetts to depart Boston and head out to war. The regiment, numbering 1,010 officers and men, and amid much celebration and fanfare, left Boston on May 28, sailing south toward the coast of South Carolina, to take part in siege operations against Charleston, the cradle of secession and birthplace of the Confederacy.[14]

For the next twenty-six months, until the regiment was formally mustered out of service on August 20, 1865, the 54th Massachusetts served entirely in the Department of the South. It campaigned and saw action in Georgia, Florida, and especially in South Carolina, being engaged in a number of skirmishes and battles, including most famously at the Battle of Battery Wagner on July 18 (the assault depicted in the concluding scenes of Glory), but also at such places as James Island, Olustee, Honey Hill, and Boykins’s Mill. Time and again, on these and other fields of battle, and even in the face of rampant racism, discrimination, and prejudice, the 54th Massachusetts proved itself an effective and hard-hitting combat regiment, and one of the best trained and disciplined units in the field, a fact commented upon by many who witnessed the regiment in action. The regiment paid a heavy price, too, in terms of numbers lost on the battlefield. Precise casualties are difficult to determine, especially those sustained at Wagner, but by war’s end, at least 176 men of the 54th Massachusetts died either in battle or in captivity in prisoner of war camps. Ninety-three men died from disease or accident, bringing the regiment’s total fatality count to 269. An additional 294 men received non-fatal wounds in combat.[15] As for the 124 soldiers of the 54th Massachusetts who hailed from south-central Pennsylvania, more than half were destined to be among the regiment’s wartime casualties. Eight succumbed to disease, several were captured, forty-two men sustained non-fatal wounds, while fifteen gave their lives on the field of battle.

Collections of Massachusetts Historical Society

The 54th experienced its first battle action on July 16, 1863, on James Island, South Carolina, and there they performed well, stubbornly holding their ground, and turning back several Confederate attacks before ultimately retiring from the field. Their performance there earned the highest praise from General Alfred Terry, who was in command of the Union forces during the engagement. Terry praised the “steadiness and soldierly conduct of the 54th MA Regiment, who were on duty at the outposts on the right and met the brunt of the attack.”[16] Among those who gave their lives at the Battle of James Island were three men from south-central Pennsylvania. Private Henry King, age 27 from Carlisle, was killed, and nineteen-year-old George Washington Street of Franklin County, received a fatal wound. Street died on July 22 and today lies at rest in the Beaufort National Cemetery. Also, among the killed was young, nineteen-year-old Cyrus Krunkleton, one of the four Krunkleton brothers from Mercersburg. The Battle of James Island was especially hard on the Krunkleton family. In addition to Cyrus, who lost his life, brothers William and Wesley were born severely wounded. William was shot in the chest and remained hospitalized until January 1864, while Wesley was shot in the right knee. The wound would never truly heal and later in life, Wesley lost the use of this injured knee. Two other soldiers from south-central Pennsylvania were wounded as well, while two others—Joseph Proctor and James Oscar Williams—were captured. Both Proctor and Williams remained in captivity until March 1865, when they were exchanged and later returned to the regiment.[17]

Two days after the regiment’s baptism by fire at James Island, the 54th Massachusetts gained its greatest glory by spearheading the dusk assault on Battery Wagner, located on the northern end of Morris Island. The attack made headlines—both North and South—and won for the regiment widespread acclaim. Although Black units had already performed well elsewhere in battle, it was this attack on Wagner that captured the most attention, then and now. As the abolitionist Thomas Wentworth Higginson, himself a commander of a Black regiment, wrote in 1897: “The attack on Fort Wagner, with the picturesque and gallant death of young Colonel Shaw, made a great impression on the North, and did more than anything else, perhaps, to convince the public that Negro troops could fight well. . .”[18] Despite its failure and the heavy casualties, the 54th’s fearless but ultimately futile attack on Wagner on the night of July 18, 1863, was truly a signal moment in the war, and a significant event in the long struggle for freedom and equality in the United States.

Among the 54th’s casualties at the Battle of Battery Wagner were many who enlisted from south-central Pennsylvania. Killed or missing and presumed dead were Privates John Snowden, age 20, from Hanover; Thomas Sheldon, age 23, from Middletown; Augustus Lewis, age 20, from Shippensburg; Corporal Robert Lyons, age 21, from Mercersburg; Privates Thomas Stoner, age 18, from Mercersburg; Ezekiel Williams, age 20, from Harrisburg, who was captured and died while in captivity; Martin Gilman, age 23 from Chambersburg, who died of his wounds sustained at Wagner on September 8, 1863; and B. Harvey Williams, age 18, a farm laborer who was born in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. In addition to these eight men from south-central Pennsylvania who died alongside Colonel Shaw at Wagner, twenty-four others were wounded.

For many of those who sustained non-fatal wounds, their lives would be forever impacted. George Fisher’s injury was so severe that he partially lost the use of his left elbow and fingers for the rest of his life, which, sadly, was only a few more years. Following his medical discharge, he returned to wife Sarah, to their home in Carlisle. There he died in April 1869 at age 30. William Raymour (or Ramer), who had been slightly wounded at James Island, was shot in the chest at Wagner. This injury led to asthma attacks and frequently to pneumonia and likely contributed to his death in 1896 at age 52.

Killed In Action at Battery Wagner, July 18, 1863

Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society

William Garrison from Chambersburg was shot in the left leg, the bullet shattering his tibia for nearly its entire length. The wound caused much pain for the rest of his life. He was discharged due to this injury in May 1864. Like Garrison, twenty-two-year-old David Demus was also discharged because of the severity of his wound. As his surgeon’s discharge certificate states, “After crossing the trench of the Fort, a minie ball struck his head over the posterior part of the Parietal bone fracturing his skull. Portions of the outer and inner tables are absent, and the soldier suffers constant pain. The head is morbidly sensitive to the direct rays of the sun. A fit case for pension,” the doctor concluded, “but unfit for the Veterans’ Reserve Corps because men of color are not allowed in it.”[19]

Thomas Burgess, a twenty-two-year-old carpenter from Mercersburg, was near Shaw when the colonel fell dead atop Wagner’s parapets. Although himself badly wounded, Burgess attempted to drag Shaw’s body down the embankment but, said Burgess, it was clear there was “no life in him.” Soon after two other soldiers were killed and their bodies fell atop Shaw’s; Burgess made his way back to safety.[20]

Two men from south-central Pennsylvania were taken prisoner during the Battle of Fort Wagner; sadly, neither made it back home. Stewart Wesley Woods from Heidlersburg, in Adams County, survived twenty months in captivity, before being exchanged in Wilmington, North Carolina, in March 1865. He died of disease just a few days later. Sergeant Alford Whiting from Carlisle, Pennsylvania, also endured twenty long and brutal months in captivity, confined, as was Woods, in Charleston and later Florence, South Carolina, before being exchanged in Wilmington in March 1865. He died of typhoid fever three months later and today lies at rest in the Alexandria National Cemetery.

Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society

Also among the 54th’s casualties during the assault on Battery Wagner was James Krunkleton. His brother Cyrus had been killed at the Battle of James Island two days earlier, the same battle where his brothers William and Wesley had been badly wounded. And now James had fallen wounded as well, meaning all four brothers fell in battle all within just 48 hours. Like most of the wounded men from the 54th who made it safely back to Union lines, James Krunkleton was conveyed by steamer to General Hospital No. 6 in Beaufort, South Carolina, where his brothers Wesley and William were already being cared for. One of the doctors treating the sick and injured at this hospital was Dr. Esther Hill Hawks, who was struck by the fact that three brothers lie there injured, side-by-side. Their hearts were heavy over the loss of Cyrus but, still, they were proud to be wearing the uniform and doing their part to rid the nation of slavery. In her diary, Dr. Hawks recorded a conversation she had with one of the Krunkleton brothers. “We offered to go when the war broke out but none would have us,” said one of the wounded brothers, “and as soon as Governor Andrew gave us a chance all the boys in our place were ready; hardly anyone who could carry a musket stayed home.”[21]

The movie Glory concludes with a depiction of the burial of the body of Colonel Shaw alongside those of his men who died during the attack on Wagner. To some, this might give the impression that the story of the 54th Massachusetts ended with this ill-fated assault. Of course, this was not the case. In fact, with this attack coming less than two months after the 54th first departed Boston, the regiment’s wartime service record was in reality just getting started. The 54th was destined to participate in several more battles by war’s end—some major, others minor in comparison—but most notably in the February 1864 Battle of Olustee. Upon this field of battle west of Jacksonville, Florida, the soldiers of the 54th once again performed well under fire, being called upon late in the engagement to help stall a victorious Confederate force and to help buy some time to allow Union General Truman Seymour to extract his shattered command from the field.[22]

At Olustee, the 54th lost eight men killed and more than 70 wounded. Among the casualties was thirty-eight-year-old Private John Miller, a native of Franklin County, who survived a wound at Wagner only to fall dead at Olustee. Two of the fighting Christy brothers in Company I were also among the casualties at Olustee. Sixteen-year-old Joseph Christy—one of the youngest soldiers in the entire regiment—sustained a minor head wound, while his older brother, twenty-one-year-old William, was initially reported as captured. It was not long before word reached camp that William died while in Confederate captivity, though it is not known exactly how. Was he wounded during the fight and later succumbed to the wound, or was he brutally murdered by vengeful Confederate soldiers?

Among the 54th’s wounded at the Battle of Olustee was Sergeant Stephen Swails. The son of Peter and Johanna Atkins Swails, Stephen Swails was born in February 1832 in Columbia, Pennsylvania, but seems to have spent much of his life in New York, working as a waiter in Cooperstown and then as a boatman in Elmira. It was from Elmira that he enlisted, perhaps in response to the direct appeals of Frederick Douglass. Swails was thirty years old and upon arrival in camp was made the First Sergeant of Company F. Sergeant Swails immediately impressed his superiors in the regiment and on February 24, 1864, two days after Swails fell severely wounded at Olustee, Colonel Hallowell wrote to Governor Andrew recommending he appoint Swails a lieutenant in recognition of his soldierly qualities as well as his heroism at Olustee. Andrew did so immediately. However, the U.S. War Department refused to recognize Swails’s rank since only white men could be commissioned officers. After much back-and-forth, the War Department relented, and Stephen Swails became the first African American commissioned officer in the United States Army. Following the war, Swails settled in South Carolina where he became a prominent attorney and newspaper editor. He soon became a leading Black voice in the Reconstruction South. He served as mayor of Kingstree, and then in the state senate for ten years. He was a delegate to the Republican Party National Convention in 1868, 1872, and 1876, and served as a major general in the state militia. Having survived an assassination attempt, Swails moved to Washington, D.C. for a time before returning to South Carolina, where he died at age 68 in May 1900.[23]

Following the Battle of Olustee and the expedition into Florida, the 54th returned to the South Carolina coast and there it remained for the duration of the conflict, being present for the fall of Charleston and participating in a number of campaigns into the interior. They saw action again at the battles of Honey Hill in November 1864, and at Camden and at Boykin’s Mill in April 1865. This battle, fought on April 18, 1865, was the 54th’s last battle. The price paid by the regiment—and by those from south-central Pennsylvania—during its twenty-six-month term of service was heavy. In addition to those who died upon the field of battle were those who died from disease. Young George Scott from Harrisburg, just twenty years old died, reportedly, of heart failure on June 8, 1863, soon after the regiment arrived in South Carolina. Chronic diarrhea claimed the lives of forty-three-year-old Edward Parks from Carlisle, twenty-one-year-old John Slider from Mercersburg, and thirty-nine-year-old Levi Bird, who was born in York, Pennsylvania. Private Charles Rideout from Mercersburg, who served alongside his brother James in Company I, died of typhoid fever in February 1865, while twenty-five-year Edward Darks, also from Mercersburg, died of either a cerebral hemorrhage or stroke on July 9, 1865. And finally, William Krunkleton, a man who had survived a wound at James Island, the battle where he his brother was killed, died of pneumonia in Georgetown, South Carolina, on April 14, 1865.

Collections of Massachusetts Historical Society

For those who had survived the war and who had not been medically or otherwise discharged, the long journey back home began in the late summer of 1865. The regiment had been stationed in Charleston, with several of its companies encamped at the Citadel. It was there, in Charleston, the birthplace of the Confederacy, where, poignantly, the soldiers of the 54th Massachusetts celebrated Independence Day, 1865. “National salutes were fired from [Forts] Sumter, Moultrie, Bee, Wagner, and Gregg,” wrote Captain Luis Emilio in his regimental history, “the harbor resounding with the explosions, bringing to memory the days of the siege. The troops paraded, the Declaration of Independence and Emancipation Proclamation were read, and orators gave expression to patriotic sentiments doubly pointed by the great way which perfected the work of the fathers.”[24] Relieved from garrison duty in the city, the regiment made its way to Mount Pleasant, South Carolina. There, on August 20, 18865, the soldiers of the 54th were mustered out of service. Boarding steamers, the surviving veterans of the famed regiment sailed north. Arriving back in Boston, the regiment received a hero’s welcome and a grand celebration. The men paraded through the city streets with two bands playing patriotic airs. A host of dignitaries turned out to welcome the men back home, including a tremendously proud Governor John Andrew. On Boston Common Colonel Hallowell formed the regiment into a hollow square and addressed the men, thanking them and praising them for their service. Following this, the regiment made its way to Charles Street where a large dinner was prepared for the men. After dinner, the men began their own journeys back to their own homes. The 54th Massachusetts Infantry was no more.[25]

By rail, by carriage, and by foot the 54th Massachusetts soldiers from south-central Pennsylvania at last made their way back to their homes and families, who were eagerly awaiting their return in places like Carlisle, Harrisburg, Chambersburg, and Mercersburg. Upon arrival there, they were greeted and warmly embraced by their mothers and fathers, their sisters, brothers, and their children. Many returned home with scars from distant battlefields; some no doubt finding it difficult transitioning from soldier back to civilian. Many returned with bittersweet tears in their eyes and with broken hearts, having lost friends and brothers. Of the four Krunkleton Brothers who marched off to war in May 1863, only two—James and Wesley—returned, both with wounds from the conflict. Charles Darks and James Rideout both returned home to Mercersburg without their brothers. Three of the four Christy Brothers made it back, while the body of William lay buried in an unmarked grave near far-away Olustee, Florida.

Courtesy of the Franklin County Historical Society

With their lives still very much ahead of them, these proud veterans resumed their lives, returning to their homes, their farms, and to their labors. William Little, who served as a sergeant in Company D, married and raised eight children. He attended school and ultimately graduated from Lincoln University. He later became the very first African American to serve on Chambersburg, Pennsylvania’s police force.

Jacob Christy of Company I played a central role in organizing the Grand Review of Black Troops that took place in Harrisburg in November 1865, serving as Chief Aid for this event. Christy later moved to Pittsburgh then took up residence at the National Soldiers’ Home in Dayton, Ohio. It was there, sadly, where Jacob Christy, who had survived a severe leg wound at Fort Wagner, met his demise. In a tragic incident, Christy was stabbed to death by a fellow veteran, a man named Benjamin Butler, who had served in the all black 55th Massachusetts Infantry. As newspaper accounts reported, Butler complained that Christy took too long during dinner one evening in passing him a bowl of oatmeal. Words were exchanged and the argument continued outside. There, and claiming self-defense, Butler pulled a knife and stabbed Christy twice in the stomach and once in the thigh, severing the femoral artery of the 67-year-old veteran.[26]

Many of the veterans of the 54th Massachusetts from south-central Pennsylvania would join either segregated or integrated posts of the Grand Army of the Republic, while some, like Jacob Christy, assumed active roles in veterans’ affairs and organizations. All were no doubt proud of their service; proud knowing that they were a part of the famed 54th, the very first all-black regiment to be recruited in the North, and proud knowing that despite the many risks involved for a black man in uniform that they willingly served to help destroy slavery and helped to extend freedom, helping to make good on the promises of their country. These men were the real soldiers of the 54th Massachusetts.

From the Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society

As historian Edwin Redkey so eloquently explained in his own study of the soldiers of the regiment,

“They came from all over the nation, from all walks of life, many as escaped slaves. Containing the history of their race in America, black, brown, and lighter hues, they proudly fought not only to save the Union but also to destroy slavery and earn their long-denied equality and their right to citizenship. Many died, more were wounded or endured disease in the struggle, and some fought their war in rebel prisons. Their honorable sacrifices and ultimate victory became a major chapter in the struggle for a just society in America. They deserve to be remembered.”[27]

Roster of South Central Pennsylvanians in the 54th Massachusetts Infantry By Company

The following is a listing of those soldiers in the 54th Massachusetts from south-central Pennsylvania, along with some pertinent biographical information. This information came from a few sources, but primarily from a perusal and examination of the regimental record books and service records held at the National Archives and available at fold3.com. Other information came from the roster contained in Luis Emilio’s regimental history, A Brave Black Regiment. Much more on the individual lives and experiences of 54th Massachusetts soldiers can be found at this excellent and exhaustive site:

https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Space:54th_Massachusetts_Volunteer_Infantry

The roster below is arranged alphabetically by Company. In addition to the soldier’s name and rank, his date of enlistment, age at enlistment, place of residence, occupation, and marital status is provided, as is any notes on his service, date of discharge, death, and burial place if known.

*Lewis Robinson: Private; 3/12/1863; age 21; Born in York, PA; Resided in Columbia, PA; Farmer; Single; Discharged: 8/20/1865.

*Henry Long: Private; 12/16/1863; age 35; Born in Washington, D.C.; Enlisted in Harrisburg, PA; Laborer; Married; Discharged: 8/20/1865.

*James Lyons: Corporal; 3/2/1863; age 34; Residence: Franklin County, PA; Farmer; Married; Discharged: 8/20/1865; Died: 3/25/1905; Buried: Veterans’ Memorial Cemetery, Erie, PA

*Edward H. Smith: Private; 3/9/1863; Residence: Middletown, PA; Farmer; Single; Discharged: 8/20/1865.

*John H. Snowden: Private; 3/14/1863; Residence: Hanover, PA; Laborer; Single; Notes: Missing and Presumed Dead at Battle of Fort Wagner, 7/18/1863.

*George Washington Street: Private; 3/11/1863; age 19; Residence: Franklin County, PA; Laborer; Single; Notes: Mortally Wounded in Battle of James Island, 7/16/1863; Died of Wounds, 7/22/1863

*Henry B. Marshall: Private; 3/16/1863; age 45; Residence: Harrisburg, PA; Cook; Married; Discharged: 7/15/1865; Detailed as Cook in Quartermaster’s Department; Medically Discharged due to rheumatism and chronic diarrhea.

*Joseph Smith Berry: Private; 4/29/1863; age 22; Residence: Franklin County, PA; Laborer; Single; Discharged: 5/29/1865; Notes: Wounded at Battle of Fort Wagner, 7/18/1863; Wounded by the explosion of a torpedo at Morris Island, 8/23/1863; Severely Wounded at Battle of Olustee, 2/22/1864; Returned to Company; Sick in Hospital, 11/1864; Medically Discharged Due to Disability.

*Sylvester Burrell: Private; 3/19/1863; age 19; Residence: Columbia, PA; Laborer; Single; Discharged: 8/20/1865; Died: 11/1/1914; Buried: Mount Bethel Cemetery, Columbia, PA

*Joseph Butler: Private; 3/16/1863; age 25; Born in Berkeley, VA; Enlisted in Harrisburg, PA; Farmer; Single; Discharged: 8/20/1865

*Richard Butler: Private; 3/15/1863; age 24; Residence: Franklin County, PA; Farmer; Single; Discharged: 8/10/1865

*James Davis: Private; 3/19/1863; age 18; Clerk; Single; Discharged: 8/20/1865; Notes: Detailed as Brigade Orderly, 12/1863-4/1865; Buried: Zion Hill Cemetery, Columbia, PA.

*George Fisher: Private; 3/25/1863; age 25; Farmer; Married; Discharged: 6/30/1864; Notes: Wounded at Battle of Fort Wagner, 7/18/1863; shot above left elbow, “partially depriving him of use of elbow and fingers;” Medically Discharged Due to Wound; Died: 4/20/1869; Buried: Lincoln Cemetery, Mechanicsburg, PA.

*Martin Gilman/Gillmore: Private; 4/29/1863; age 23; Residence: Chambersburg, PA; Farmer; Married; Notes: Mortally Wounded in Leg at Battle of Fort Wagner, 7/18/1863; Leg Amputated; Died at General Hospital, Beaufort, SC, from Wound, 9/8/1863; Buried: Beaufort National Cemetery, SC.

*Franklin Green: Private; 3/16/1863; age 17; Born in Suffolk County, VA; Enlisted in Harrisburg, PA; Laborer; Single; Discharged: 8/20/1865.

*Robert Kane: Corporal; 3/19/1863; age 21; Residence: Columbia, PA; Laborer; Single; Discharged: 8/20/1865.

*William Little: Sergeant; 3/25/1863; age 20; Residence: Chambersburg, PA; Laborer/Butcher; Single; Discharged: 8/20/1865; Died: 3/14/1926; Buried: Lebanon Cemetery, Chambersburg, PA.

*Hezekiah Allen McPherson: Private; 3/16/1863; age 23; Born in Prince George’s County, MD; Enlisted in Harrisburg, PA; Laborer; Single; Discharged: 8/20/1865; Notes: Detailed as Hospital Attendant, 11/1863-3/1865. Died: 10/4/1920; Buried: Arlington National Cemetery, Arlington, VA.

*Andrew Meads: Private; 3/16/1863; age 21; Born in Adams County, PA; Residence: Chambersburg, PA; Laborer; Single; Discharged: 8/20/1865; Died: 4/6/1911; Buried: Mount Bethel Cemetery, Columbia, PA.

*John Plowden: Corporal; 4/29/1863; age 22; Residence: Chambersburg, PA; Laborer; Single; Discharged: 5/29/1865; Notes: Wounded at Battle of Fort Wagner, 7/18/1863; Buried: Lebanon Cemetery, Chambersburg, PA.

*George Scott: Private; 3/25/1863; age 20; Residence: Harrisburg, PA; Laborer; Single; Notes: Died in Regimental Hospital, 6/8/1863, of Heart Disease.

*John H. Stotts: Corporal; 3/19/1863; Residence: Marietta, PA; Laborer; Married; Discharged: 8/20/1865; Died: 1893; Buried: Mount Bethel Cemetery, Columbia, PA

*John J. “Jack” Turner: Private; 3/19/1863; age 20; Laborer; Single; Discharged: 5/29/1865; Notes: Wounded by Bayonet in Foot at Battle of Fort Wagner, 7/18/1863; Buried: Zion Hill Cemetery, Columbia, PA.

*Thomas A. Brown: Private; 12/16/1863; Born in Maryland; Residence: Middletown, PA; Laborer; Married; Discharged: 9/28/1865.

*George Butler: Private; 12/16/1863; age 23; Residence: Chambersburg, PA; Laborer; Married; Discharged: 8/20/1865.

*Edward Davis: Private: 4/30/1863; age 20; Residence: Harrisburg, PA; Moulder; Single; Discharged: 8/20/1865; Died: 3/18/1897; Buried; Wildwood Cemetery, Williamsport, PA.

*Jesse Gray: Private; 4/30/1863; age 30; Residence: Harrisburg, PA; Laborer; Single; Discharged: 8/20/1865.

*Edward Webster: Private; 3/29/1863; Residence: Harrisburg, PA; Laborer; Single; Discharged: 8/20/1865.

*Charles Bowser: Private; 4/8/1863; age 18; Residence: Middletown, PA; Laborer; Single; Discharged: 8/20/1865.

*William Carroll: Private; 4/8/1863; age 22; Residence: Harrisburg, PA; Laborer; Single; Discharged: 8/20/1865.

*Philip Cole: Corporal; 4/8/1863; age 19; Born in Havre de Grace, MD; Residence: Middletown, PA; Laborer; Single; Discharged: 8/20/1865.

*William Cole: Private; 4/8/1863; age 27; Born in Havre de Grace, MD; Residence: Middleport, PA; Laborer; Single; Discharged: 6/10/1863; Notes: “Unfit for Duty since enlistment;” chronic rheumatism affliction of the knees, which existed before his enlistment; discharged by mustering officer.

*Charles Cunningham: Private; 4/8/1863; age 19; Residence: Middletown, PA; Farmer; Single; Discharged: 8/20/1865.

*Ferdinand Cunningham: Private; 4/8/1863; Residence: Franklin County, PA; Farmer; Single; Discharged: 8/20/1865.

*Thomas H.W. Dadford: Private; 12/4/1863; Residence: Harrisburg, PA; Barber; Single; Discharged: 8/20/1865.

*William T. Freeman: Private; 4/8/1863; age 25; Residence: York County, PA; Farmer; Single; Discharged: 8/20/1865.

*Samuel Moles: Private; 4/8/1863; age 23; Residence: York County, PA; Laborer/Stablehand; Single; Discharged: 8/20/1865. Notes: Wounded Severely in Hand at Battle of Fort Wagner, 7/18/1863.

*Thomas Rice: Private; 4/8/1863; Residence: Franklin County, PA; Laborer; Married; Discharged: 8/20/1865; Notes: Wounded Slightly in Hand at Battle of Olustee, 2/20/1864.

*Stephen Swails: 1st Lieutenant; 4/1863; age 30; Born in Columbia, PA; Residence: Cooperstown, NY; Boatman and Hotel Porter; Single; Discharged: 8/20/1865; Notes: Son of Peter and Johanna Atkins Swails; Enlisted at Rank of 1st Sergeant; Wounded in Head at Battle of Olustee, 2/20/1864; Wounded in Battle near Camden, SC, 4/11/1865; Promoted to 2nd Lieutenant by Gov. Andrew, 3/11/1864, but Commission and Rank not recognized by War Department until 1/17/1865; one of the very first African American commissioned officers in U.S. Army; Died: 5/17/1900; Buried: Humane and Friendly Cemetery, Charleston, SC.

*Andrew Thomas: Private; 4/18/1863; age 18; Residence: Dauphin County, PA; Boatman; Single; Discharged: 8/20/1865.

*Sheldon Thomas: Private; 4/8/1863; age 23; Residence: Middletown, PA; Laborer; Single; Notes: Killed in Action at the Battle of Fort Wagner, 7/18/1863.

*Peter Washington: Private; 4/8/1863; age 21; Born in Jefferson County, VA; Residence: Middletown, PA; Coachman; Single; Discharged: 8/20/1865.

*John Anderson: Private; 4/18/1863; age 18; Born in North Carolina; Residence: Carlisle, PA; Laborer/Baker; Single; Discharged: 8/20/1865.

*Aaron Cummings: Private; 4/12/1863; age 22; Residence: York County, PA; Laborer; Married; Discharged: 8/20/1865; Notes: Wounded in Right Knee and Left Thigh at Battle of Olustee, 2/20/1864.

*Charles N. Demus: Private; 12/16/1863; age 18; Residence: Chambersburg, PA; Laborer; Single; Discharged: 8/20/1865.

*George Ellender: Private; 4/12/1863; age 33; Enlisted in York County, PA; Forgeman; Single; Discharged: 8/20/1865; Notes: Wounded Slightly at Battle of Fort Wagner, 7/18/1863; Wounded Severely in Right Arm at Battle of Olustee, 2/20/1864; Detached as Hospital Attendant, 1/1865-7/1865.

*William Garrison: Private; 5/12/1863; age 25; Born in Frederick County, VA; Enlisted in Chambersburg, PA; Laborer; Single; Discharged: 5/21/1864; Notes: Wounded Severely in Leg at Battle of Fort Wagner, 7/18/1863; Discharged by Surgeon’s Certificate for Disability.

*John E. Johnson: Private and Principal Musician; 4/14/1863; Residence: Harrisburg, PA; Barber; Single; Discharged: 10/12/1865; Notes: Also served in U.S. Navy; Promoted to Principal Musician, 5/1/1864; Reduced and Assigned to Company E, 54th MA, 10/25/1864; In Arrest at Morris Island, SC, “Awaiting trial in regimental guard house;” Deserted from Charleston in May 1865; Surrendered to Military Authorities; Ordered Discharged, 10/12/1865; Relieved from charge of Desertion on condition of forfeiting all pay, bounty, and allowances due to him.

*John Miller: Private; 5/12/1863; age 38; Born in Franklin County, PA; Enlisted in Allegheny City, PA; Seaman, Married; Notes: Wounded at Battle of Fort Wagner, 7/18/1863; Killed in Action at the Battle of Olustee, 2/20/1864.

*John Oakey/Oaky: Private; 4/12/1863; age 24; Born in Baltimore, MD; Enlisted in Columbia, PA; Laborer; Married; Discharged: 8/20/1865; Died: 7/22/1905; Buried: Wildwood Cemetery, Williamsport, PA.

*William Raymour/Ramer: Private; 4/12/1863; age 19; Residence: Shippensburg, PA; Laborer; Single; Discharged: 8/20/1865; Notes: Wounded in Chest at Battle of Fort Wagner, 7/18/1863; Suffered from asthma and pneumonia; Ear drum shattered during battle on James Island; Died: 2/9/1896; Buried: Lincoln Memorial Cemetery, Pittsburgh, PA.

*John Green: Private; 4/15/1863; age 31; Residence: Carlisle, PA; Laborer; Single; Discharged: 9/12/1865; Notes: Wounded Severely in Left Arm at Battle of Boykin’s Mill. SC, 4/18/1865; Discharged by Surgeon’s Certificate due to Disability.

*John S. Green: Private; 4/15/1863; age 25; Born in Mount Rock, PA; Enlisted in Carlisle, PA; Laborer; Single; Discharged: 8/20/1865.

*Philip Holmes a.k.a Phlip King: Private; 4/29/1863; age 20; Residence: Chambersburg, PA; Hostler; Single; Notes: Deserted, 5/19/1865; Apprehended and placed in Confinement, 7/21/1865; Dropped from the rolls, 7/28/1865.

*Robert B. Howard: Private; 4/15/1863; age 18; Residence: Carlisle, PA; Laborer; Single; Discharged: 8/20/1865; Notes: Brother of Charles Howard, Co. I, 54th MA; Died: 8/1875; Buried: Lincoln Cemetery, Carlisle, PA.

*Henry King: Private; 4/15/1863; age 27; Residence: Carlisle, PA; Laborer; Single; Notes: Killed in Action at the Battle of James Island, 7/16/1863.

*James Lane: Private; 4/17/1863; age 22; Residence: Mercersburg, PA; Laborer; Single; Discharged: 8/20/1865.

*Milton Lane: Private; 4/15/1863; age 28 or 31; Residence: Carlisle, PA; Laborer; Single; Discharged: 8/20/1865; Notes: Wounded Slightly in Chest at Battle of Fort Wagner, 7/18/1863.

*Augustus Lewis: Private; 4/29/1863; age 20; Residence: Shippensburg, PA; Laborer; Single; Notes: Killed in Action at Battle of Fort Wagner, 7/18/1863.

*Joseph Proctor: Private; 4/21/1863; age 24; Born in Maryland; Residence: Franklin County, PA; Cook; Single; Discharged: 6/23/1865; Notes: Initially reported as Killed in Action, but actually captured at Battle of James Island, 7/16/1863; Held in Prisoner of War Camps until Exchanged, 3/4/1865; Returned to Regiment.

*James F. Price: Private; 4/21/1863; Born in Wrightsville, PA; Enlisted in Buffalo, NY; Laborer; Single; Discharged: 8/20/1865.

*James T. Russell: Private; 4/13/1863; age 35; Residence: Gettysburg, PA; Laborer; Single; Discharged: 9/28/1865.

*James Oscar Williams: Private; 4/15/1863; age 35; Laborer; Single; Discharged: 8/20/1865; Notes: Wounded and Captured at Battle of James Island, 7/16/1863; Held in Prisoner of War Camps until Exchanged, 3/4/1865; Returned to Regiment.

*William Wright: Private; 4/15/1863; age 22; Born in Virginia; Enlisted in Carlisle, PA; Laborer; Single; Discharged: 8/20/1865.

*Nathaniel Bell: Private; 4/22/1863; age 23; Residence: Carlisle, PA; Laborer; Married; Discharged: 8/20/1865.

*William Bell: Private; 4/22/1863; age 21; Residence: Carlisle, PA; Brickmaker; Single; Discharged: 8/20/1865.

*John Bradford: Private; 4/26/1863; age 21; Residence: Harrisburg, PA; Laborer; Single; Discharged: 8/20/1865.

*George Brummzig: Private; 4/22/1863; age 20; Residence: Mercersburg, PA; Laborer; Single; Discharged: 8/20/1865; Buried: Zion Union Cemetery, Mercersburg, PA.

*Thomas E. Burgess: Private; 4/22/1863; age 22; Residence: Mercersburg, PA; Carpenter; Single; Discharged: 8/20/1865; Notes: Wounded Severely at Battle of Fort Wagner, 7/18/1863.

*David Butler: Private; 4/29/1863; age 29; Born in Franklin County, PA; Enlisted in Carlisle, PA; Farmer; Married; Discharged: 8/10/1865; Died: 3/16/1914; Buried: Union Cemetery. Carlisle, PA. *George Carson: Private; 4/22/1863; age 21; Residence: Mercersburg, PA; Laborer; Single; Discharged: 8/20/1865.

*Jacob Christy: Private; 4/22/1863; age 19; Residence: Mercersburg, PA; Laborer; Single; Discharged: 8/20/1865; Notes: Son of Jacob and Catherine Christy; Brother of Joseph, Samuel, and William Christy; Wounded Severely in Leg at Battle of Fort Wagner, 7/18/1863; Served as Chief Aid for Grand Review of USCT in Harrisburg, 11/1865; Died: 8/19/1913; Buried: Dayton National Cemetery, Dayton, OH.

*Joseph Christy: Private; 4/22/1863; age 16; Residence: Mercersburg, PA; Woodcutter, Single; Discharged: 8/20/1865; Notes: Son of Jacob and Catherine Christy; Brother of Jacob, Samuel, and William Christy; Notes: Wounded Slightly in Head at Battle of Olustee, 2/20/1864; Buried: Zion Union Cemetery, Mercersburg, PA.

*Samuel Christy: Private: 4/22/1863; age 23; Residence: Mercersburg, PA; Laborer; Single; Discharged: 8/20/1865; Notes: Son of Jacob and Catherine Christy; Brother of Jacob, Joseph, and William Christy; Died: 3/28/1905; Buried: Zion Union Cemetery, Mercersburg, PA.

*William Christy: Private; 4/22/1863; age 21; Residence: Mercersburg, PA; Laborer; Single; Notes: Son of Jacob and Catherine Christy; Brother of Jacob, Joseph, and Samuel Christy; Notes: Listed as Missing-in-Action at Battle of Olustee, 2/20/1864; Later discovered to have died while in enemy hands.

*Thomas Cuff: Private; 4/22/1865; age 21; Residence: Mercersburg, PA; Quarryman; Married; Discharged: 8/20/1865; 1882; Buried: Zion Union Cemetery, Mercersburg, PA.

*Thomas Dorsey: Sergeant; 4/26/1863; age 23; Residence: Harrisburg, PA; Laborer; Single; Discharged: 8/20/1865.

*Isaiah Harrison: Private; 4/22/1863; age 19; Residence: Mercersburg, PA; Laborer; Single; Discharged: 10/19/1865; Died: 4/18/1926; Buried: Union Cemetery, Carlisle, PA.

*Charles “Charlie” Howard: Corporal; 4/29/1863; age 26; Waiter; Married; Discharged: 8/20/1865; Notes: Brother of Robert Howard, Co. H, 54th MA; Died: 8/8/1902; Buried: Union Cemetery, Carlisle, PA.

*George Jackson: Private; 4/22/1863; age 19; Born in Clark County, VA; Enlisted in Harrisburg, PA; Laborer; Single; Notes: Killed While on Fatigue Duty, in Trenches as Fort Wagner, 10/9/1863; Struck in Head by Shell Explosion; Buried: Beaufort National Cemetery, Beaufort, SC.

*Stanley Johnson: Private: 4/29/1863; age 18; Residence: Mercersburg, PA; Farmer; Single; Notes: Wounded at Battle of Fort Wagner, 7/18/1863; Detailed as Nurse in Hospital at Morris Island, SC, 10/13/1863; Died of Wounds Received in Action, 4/21/1864.

*John Lee: Private; 12/16/1863; age 35; Residence: Harrisburg, PA; Laborer; Married; Discharged: 7/12/1865; Discharged: 1/6/1865; Notes: Left his home in Harrisburg, PA, in November 1863, and journeyed to Boston to Enlist; on 1/2/1864, he received a 15-day furlough to return home to bury two of his children who died of disease; along the way, and while in New York City, he was assaulted and had his ribs broken; with the assistance of two men, he was taken to a ferry to Jersey City, NJ, and from there, traveled to Harrisburg, where he remained until 5/28/1864; sent to Camp William Penn, and from there to Morris Island, SC, where he finally joined up with 54th; however, he was discharged for physical disability, on 1/6/1865.

*Robert Lyons: Corporal; 4/29/1863; age 21; Residence: Mercersburg, PA; Farmer; Single; Notes: Missing and Presumed Dead at Battle of Fort Wagner, 7/18/1863.

*George Morse: Private; 4/22/1863; age 26; Born in Warrenton, VA; Enlisted in Fayetteville, PA; Blacksmith; Single; Discharged: 8/20/1865; Notes: Wounded at Battle of Fort Wagner, 7/18/1863; Wounded at the Battle of Olustee, 2/20/1864.

*Edward Parks: Private; 4/29/1863; age 43; Residence: Carlisle, PA; Hostler; Married; Notes: Died of Dysentery, Morris Island, SC, 10/3/1863.

*Charles Rideout: Private; 4/27/1863; age 22; Residence: Mercersburg, PA; Farmer/Laborer; Single; Notes: Brother of James Rideout; Died of Typhoid Fever, Beaufort, SC, 2/17/1875; Buried: Beaufort National Cemetery, Beaufort, SC.

*James Rideout: Private; 4/22/1863; age 17; Residence: Mercersburg, PA; Laborer; Single; Discharged: 8/20/1865; Notes: Brother of Charles Rideout; Died: 6/29/1902; Buried: Zion Union Cemetery, Mercersburg, PA.

*John Slider: Private; 4/22/1863; age 21; Residence: Mercersburg, PA; Laborer; Single; Notes: Wounded at Battle of Fort Wagner, 7/18/1863; Died of Chronic Diarrhea, Charleston, SC, 7/28/1865.

*James H. Smith: Corporal; 4/26/1863; age 22; Residence: Carlisle, PA; Laborer; Single; Discharged: 8/20/1865.

*William Stevenson: Private; 4/22/1863; age 18; Residence: Fayetteville, PA; Laborer; Single; Discharged: 8/20/1865.

*Thomas Stoner: Private; 4/22/1863; age 18; Residence: Mercersburg, PA; Laborer; Single; Notes: Missing and Presumed Dead at Battle of Fort Wagner, 7/18/1863.

*Jefferson Teale: Private; 4/29/1863; age 31; Born in Virginia; Residence: Mercersburg, PA; Farmer; Single; Discharged: 8/20/1865; Notes: Wounded in Hand at Battle of Olustee, 2/20/1864; Died: 12/18/1889; Buried: Zion Union Cemetery, Mercersburg, PA.

*Andrew Valentine: Private; 4/22/1863; age 21; Born in Baltimore, MD; Enlisted in Chambersburg, PA; Brickmaker; Single; Discharged: 8/20/1865.

*Hezekiah Watson: Corporal; 4/22/1863; age 18; Residence: Mercersburg; Quarryman and Barber; Single; Discharged: 8/20/1865; Notes: Brother of Jacob Watson, Co. K, 54th MA; Wounded Slightly in Left Hand at Battle of Fort Wagner, 7/18/1863; Died: 3/1880; Buried: Zion Union Cemetery, Mercersburg, PA.

*Alfred (Alford) Whiting: Sergeant; 4/22/1863; age 23; Residence: Carlisle, PA; Waiter; Married; Notes: Wounded and Captured at Battle of Fort Wagner, 7/18/1865; Confined in Prisoner of War Camps until Exchanged, 3/4/1865; Died from Typhoid Fever, 6/26/1865; Buried: Alexandria National Cemetery, Alexandria, VA.

*B. Harvey Williams: Private; 4/22/1863; age 18; Born in Gettysburg, PA; Enlisted in Chester County, PA; Farmer; Single; Notes: Missing and Presumed Dead at Battle of Fort Wagner, 7/18/1863.

*Ezekiel Williams: Private; 4/26/1863; age 20; Residence: Harrisburg, PA; Laborer; Single; Notes: Captured and Presumed Dead at Battle of Fort Wagner, 7/18/1863.

*Stewart Wesley Woods: Private; 4/29/1863; age 27; Residence: Heidlersburg, PA; Laborer; Single; Notes: Captured at Battle of Fort Wagner, 7/18/1863; Confined in Prisoner of War Camps until Exchanged, 3/4/1865; Died of Disease in Wilmington, NC, 3/15/1865.

*William H. Burgess: Private; 5/6/1863; age 20; Residence: Mercersburg, PA; Farmer; Married; Discharged: 8/25/1865; Wounded at Battle of Fort Wagner, 7/18/1865.

*William Burgess: Private; 5/6/1863; age 20; Residence: Mercersburg, PA; Single; Discharged: 8/20/1865; Notes: Wounded at Battle of Fort Wagner, 7/18/1863.

*Arthur Carson: Private; 5/6/1863; age 25; Residence: Mercersburg, PA; Laborer; Married; Discharged: 8/20/1865; Died: 11/16/1880; Buried: Zion Union Cemetery, Mercersburg, PA.

*David Demus: Private; 5/6/1863; age 22; Residence: Mercersburg, PA; Farmer; Married; Discharged: 6/4/1865; Notes: Wounded Severely in Head at Battle of Fort Wagner, 7/18/1863; Discharged by Surgeon’s Certificate for Disability.

*George Demus: Private; 5/6/1863; age 18; Residence: Mercersburg, PA; Farmer; Single; Discharged: 8/20/1865; Buried: Zion Union Cemetery, Mercersburg, PA.

*Charles “Charley” Darks/Darkes: Private; 5/6/1863; age 18; Residence: Mercersburg, PA; Farmer; Single; Discharged: 8/20/1865; Notes: Wounded at Battle of Olustee, 2/20/1864; Buried: Brethren Cemetery, Big Cove Tannery, PA

*Edward Darks/Darkes: Private; 5/6/1863; age 25; Residence: Mercersburg, PA; Farmer; Married; Notes: Died of Apoplexy in General Hospital No. 2, 7/9/1865.

*Cyrus Krunkleton: Private; 5/6/1863; age 19; Residence: Mercersburg, PA; Farmer; Single; Notes: Son of Wesley and Susan Krunkleton; Brother of James, William, and Wesley Krunkleton; Killed in Action at the Battle of James Island, 7/16/1863.

*James Krunkleton: Private; 5/6/1863; age 19; Farmer; Single; Discharged: 6/29/1865; Notes: Son of Wesley and Susan Krunkleton; Brother of Cyrus, William, and Wesley Krunkleton; Wounded at Battle of Fort Wagner, 7/18/1863; Died: 6/23/1899; Buried: Lebanon Cemetery, Chambersburg, PA.

*William Krunkleton: Private; 5/6/1863; age 21; Residence: Mercersburg, PA; Farmer; Single; Notes: Son of Wesley and Susan Krunkleton; Brother of Cyrus, James, and Wesley Krunkleton; Wounded Severely in Chest at Battle of James Island, 7/16/1863; Returned to Regiment, summer 1864; Fell ill with pneumonia; Died at Regimental Hospital at Georgeton, SC, 4/14/1865.

*Wesley Krunkleton: Private; 5/6/1863; age 24; Residence: Mercersburg, PA; Farmer; Single; Discharged: 8/20/1865; Notes: Son of Wesley and Susan Krunkleton; Brother of Cyrus, James, and William Krunkleton; Wounded in Right Knee at Battle of James Island, 7/16/1863; Returned home to Mercersburg; Later lost usage of right knee; suffered from rheumatism; Died: 10/31/1902; Buried: Zion Union Cemetery, Mercersburg, PA.

*Jessie Lawson: Private; 5/5/1863; age 31; Born in Sandy Lake, PA; Enlisted in Franklin County, PA; Farmer; Single; Discharged: 8/20/1865.

*Thomas McCullar: Private; 5/6/1863; age 22; Residence: Mercersburg, PA; Farmer; Married; Discharged: 8/20/1865; Notes: Wounded in Left Heel at Battle of Boykin’s Mill, SC, 4/18/1865; Died: 4/22/1893; Buried: Zion Union Cemetey, Mercersburg, PA.

*John Shirk: Corporal; 5/6/1863; age 20; Residence: Shippensburg, PA; Farmer; Married; Discharged: 8/20/1865; Died: 2/20/1913; Buried: Locust Grove Cemetery, Shippensburg, PA

*David E. Thompson: Corporal; 5/6/1863; age 20; Born in Boonsboro, MD; Enlisted in Shippensburg, PA; Farmer; Single; Discharged: 8/20/1865; Died: 5/2/1890; Buried: Forest Hill Cemetery, Dunmore, PA.

*Jacob Watson: Sergeant; 5/6/1863; age 20; Residence: Mercersburg, PA; Butcher; Married; Discharged: 8/20/1865; Notes: Brother of Cpl. Hezekiah Watson, Co. I.

NPS Photo

For Further Reading

Adams, Virginia M., ed. On the Altar of Freedom: A Black Soldier’s Civil War Letters from the Front: Corporal James Gooding. New York: Warner Books, 1991.

Blatt, Martin, Thomas J. Brown, and Donald Yacovone, eds. Hope and Glory: Essays on the Legacy of the 54th Massachusetts Regiment. Boston: University of Massachusetts Press, 2001.

Burchard, Peter. One Gallant Rush: Robert Gould Shaw and his Brave Black Regiment. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1965.

Duncan, Russell. Where Death and Glory Meet: Colonel Robert Gould Shaw and the 54th Massachusetts Infantry. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1999.

Egerton, Douglas. Thunder at the Gates: The Black Civil War Regiments that Redeemed America. New York: Basic Books, 2016.

Emilio, Luis. A Brave Black Regiment: History of the Fifty-fourth Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, 1863-1865. Boston: The Boston Book Company, 1894.