Last updated: May 13, 2024

Article

50 Nifty Finds #49: Happy Little Trees

Historically National Park Service (NPS) landscape architects were the artists of the NPS. In addition to their “day jobs,” they were called upon to design posters, elements of the uniform, and NPS emblems like the eagle, sequoia cone, and arrowhead. Beginning in the 1960s and 1970s the NPS began hiring some of the best graphic design and advertising firms in the country to create or update logos and symbols to highlight special programs and anniversaries and to ensure a consistent look in its print materials. How is it, then, that Robert C. Osborn—a cartoonist, caricaturist, and satiric commentator known for his “images of bloated power, violence, and death”—came to draw one of the National Park Service’s most feel-good symbols?

The Symbol of Summer

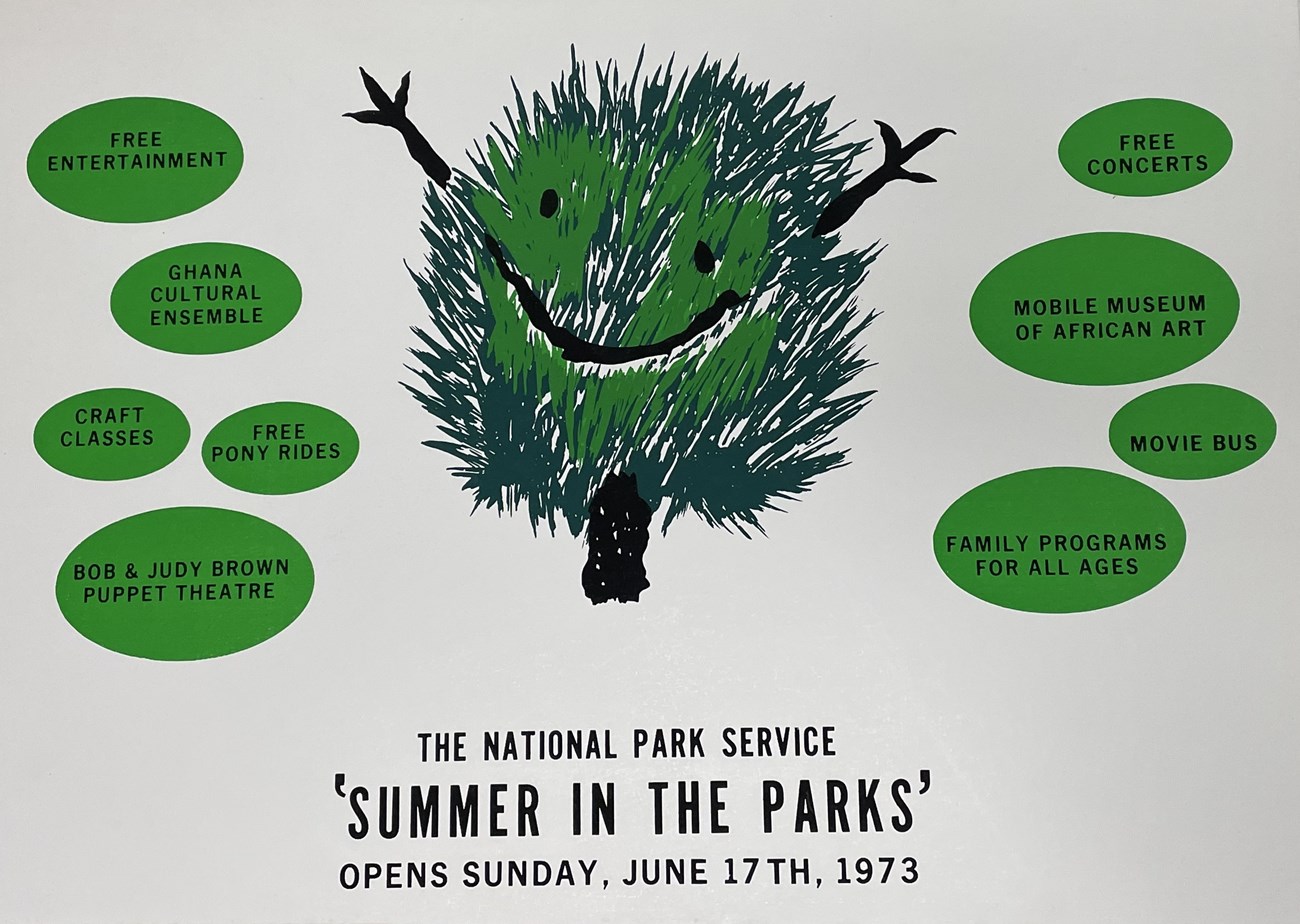

In July 1968 the NPS launched an innovative, community-based recreation program called Summer in the Parks. Partnering with local African American leaders; Washington, DC, government officials; volunteer organizations; and public-space experts, the NPS offered a wide range of free activities including concerts, children’s programming, and recreational opportunities designed to bring residents into national parks and other locations across the city.

Russel Wright, a principal force behind the project, and Tom McCann, NPS program coordinator, determined that a logo was needed to represent Summer in the Parks. Wright asked McCann’s kids to draw what a summer in the park meant to them. Two drew a tree; the third added a smile. Those simple ideas led Osborn to create the “Laughing Tree” logo in early 1968.

In 1969 Wright called the logo “good contemporary design,” and noted that, “the color scheme of brilliant blue and green with white was fresh.” Osborn’s logo became synonymous with the program. It was used on posters, banners, handbills, buttons, clothing, kites, vehicles, tents, and trash cans. As Wright pointed out, “This not only advertised the program, it created a mood for the activities and gave to the program a character of freshness and distinction.”

Robert C. Osborn

Robert Chesley Osborn was born in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, on October 26, 1904. Despite beginning his interest in art at four years old, Osborn later noted, “I was a very slow, very naive learner, thank heaven.” By seven, his humorous sports-related drawings were published in Junior Advance and The Quiver. When he was 12, he began sending cartoon ideas to cartoonist Clare Briggs at the Chicago Tribune, some of which were used. As a child he frequently visited the Art Institute in Chicago with his family. He attended Oshkosh High School and Oshkosh Normal School (later Oshkosh State College).

As a freshman at the University of Wisconsin, Osborn developed an ulcer and had to take a year off to recuperate. In fall 1924 he transferred to Yale College, where he majored in English, studied fine art, and served as art editor of The Yale Record. He began drawing advertisements, which he sold for $5 each. He also got a job as a caricaturist for the New Haven Register. In March 1928 he tied for fourth place among more than 10,000 drawings submitted by 1,600 artists in a national art contest. After graduating in 1928, with $1,500 earned by selling his drawings, tutoring children, and teaching them to sail, Osborn spent a year and a half in Europe, studying at the British Academy in Rome and the Academie Scandinav in Paris. While in Italy in 1929, he saw the fascist Prime Minister Benito Mussolini emerge to cheering crowds. He later described him as “the first chest-thumping, bumptious fool to plague me.”

Later that year he returned to the United States to teach painting and Greek philosophy at the Hotchkiss School in Lakeville, Connecticut. He also coached football and trapshooting at the school. In the summers he returned to Paris (1930) and Austria (1933) to continue studying art.

Osborn’s ulcer perforated in 1934. After recovering from surgery, he returned to Europe in 1935 with $1,335 from his art sales in his pocket. He studied art in a Paris academy and painted his way through France, Spain, Portugal, Belgium, Germany, Holland, Austria, Hungary, and England. While tutoring students in Austria in 1935, he attended a rally held for Adolf Hitler with two local women. As Hitler began to “speak, then shout, the [crowd] seemed charged with a terrible vindictive, then hating, then glorifying emotion. I couldn’t believe what I was hearing and seeing, but the two young Austrian girls were still crying [as we left].”

Osborne returned to the United States in fall 1937, painting in New York City and Wisconsin. In January 1939 he returned to Portugal with a commission to paint a mural. Returning to the United States after the Munich Agreement allowed Germany to annex part of Czechoslovakia, he tried to enlist in the Canadian Royal Air Force but was turned down because of his persistent ulcer. He enlisted in the US Naval Reserve in March 1941. He wanted to enlist in the US Navy on December 8, 1941, the day after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, but his ulcer made his dream to serve as a pilot impossible.

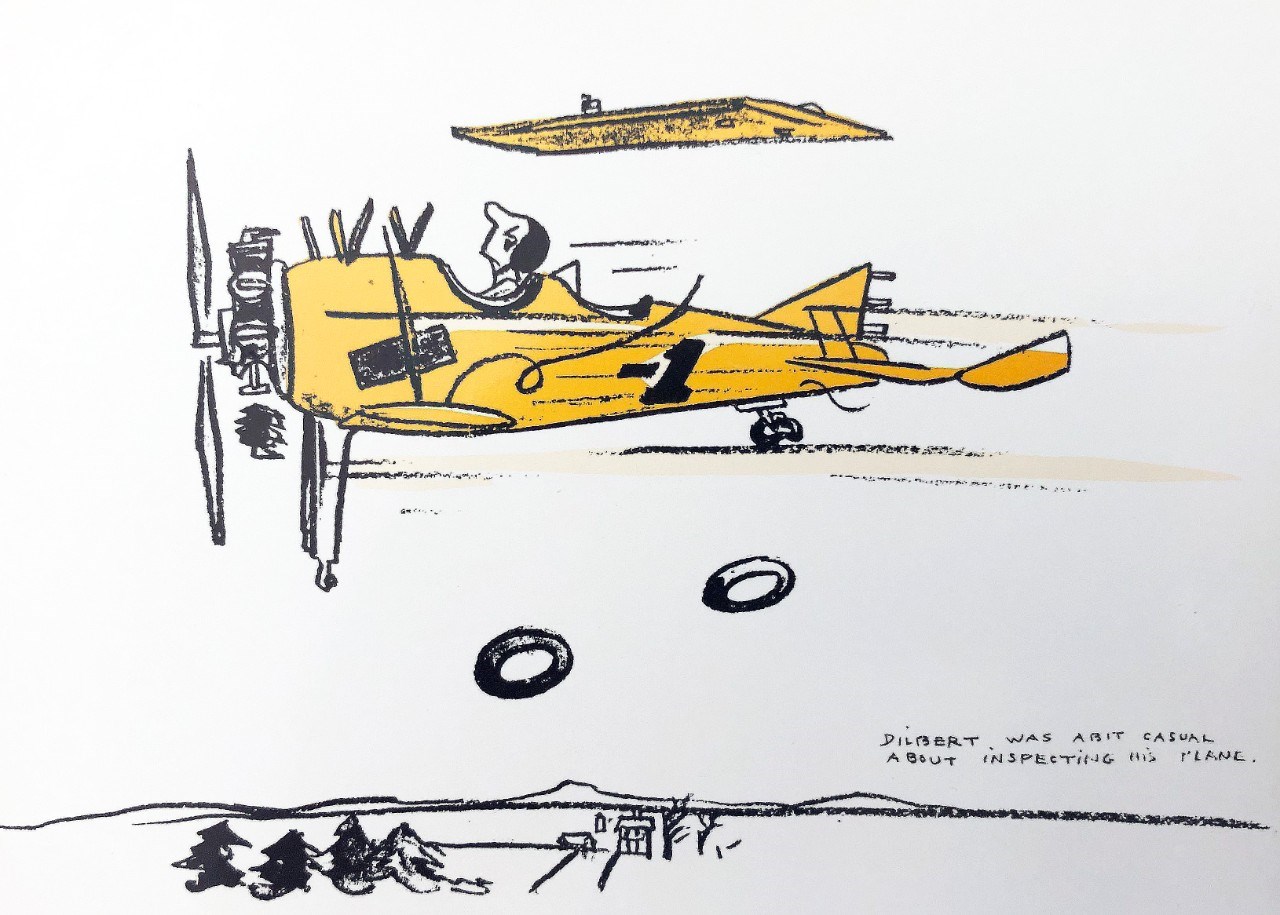

Because he had published a few “how-to” books with cartoon illustrations before the war, he was assigned to a communication unit. He learned the art of speed drawing, creating more than 40,000 drawings for navy training manuals and 2,000 education posters for pilots during the war. Osborne was sent to various naval air stations and the Pacific to study safety problems and draw illustrations for the manuals.

In 1942 he created a cartoon character named Dilbert Groundloop. Osborn described him as “a dumb but cheerful cadet pilot whose mistakes were a constant menace.” The Navy created a “Don’t be a Dilbert” safety campaign around the character. Other Osborn creations, such as Spoiler (an error-prone airplane mechanic) and Post Script “Grampaw” Pettibone (an experienced pilot who provided commentary on Dilbert’s mistakes) joined Dilbert. In 1943 Osborn’s book Dilbert: Just an Accident Looking for a Place to Happen! was published.

In March 1944 Osborn married Elodie Courter, a curator at the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) in New York. They went on to have two sons and eventually settled in Salisbury, Connecticut. Before the war was over, however, the navy sent Osborn to the Pacific Theater to learn first-hand about safety issues and life on aircraft carriers. While there he witnessed the battles of Saipan and Iwo Jima. Osborn attained the rank of lieutenant commander before he was honorably discharged in December 1945. He was awarded the navy’s Legion of Merit for his artistic contributions and “his loyal and enthusiastic labors [which] contributed materially to the effectiveness and survival in combat of navy pilots and air crewmen.”

In what must have been a childhood dream come true, his “Dilbert” cartoons were exhibited at the Chicago Art Institute in January 1945. In 1946 other examples of his work were exhibited at the Modern Museum of Art in New York. Osborn continued to draw Dilbert and his other WWII-era characters for military and aviation magazines, postwar training manuals, and other military publications. In 1946 he published War Is No Damn Good! condemning the use of nuclear weapons. It’s believed to be one of the first anti-nuclear publications.

Osborn’s reputation as a cartoonist and satirist continued to grow after war. In 1952 his series of “Who, Me?” cartoons for the Traveler Safety Service were printed in newspapers. He developed a career commenting on social issues, politics, and other topics. He famously drew Senator Joseph McCarthy in a “way that made him look like a rejected model for Frankenstein’s monster.” Through his drawings he ridiculed presidents from Lydon B. Johnson to Ronald Reagan.

Osborn wrote or illustrated dozens of books, including Low and Inside (1953), Osborn on Leisure (1957), The Vulgarians (1960), Mankind May Never Make It (1968), Missile Madness (1970), Osborn on Osborn (1982), and Osborn on Conflict (1984). He also wrote three books about catching trout, shooting quail, and shooting ducks. His illustrations appeared in many socially conscious books written by others, as well as in Life, Harper's, Fortune, Look, The New Republic, Horizon, The New York Times, Esquire, and other publications. In 1959 he was awarded the navy’s Distinguished Public Service Award for “outstanding contributions to the Department of the Navy in the fields of flight safety and public information.” In 1964 he was awarded an honorary PhD in fine arts from the Maryland Institute’s College of Art. In 1977 his contributions to the US Navy were recognized when he was named an Honorary Naval Aviator.

Osborn’s art is in numerous public and private collections including the Library of Congress, Smithsonian American Art Museum, and Metropolitan Museum of Art. His papers are at theBeinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University. Osborn died in 1994 at his home in Salisbury. He was 90 years old.

An Interesting Choice

Many sources state that Osborn was the artist, and many surviving examples of the Laughing Tree image are signed, leaving no doubt that they are correct. Given his artistic style and cutting commentary throughout his career, he was an odd choice to develop the Summer in the Parks logo. Despite intensive research efforts, we haven’t been able to determine why he was the chosen to refine the design first presented by McCann’s children. He doesn’t mention it in a 1974 oral history interview for the Archives of American Art.

Although Osborn visited Yellowstone National Park with his family when he was 12 years old, there is no evidence that he had any other connection to the NPS. As an adult he lived in Connecticut, not Washington, DC, where many other artists would have been readily available to create the logo. Furthermore, there is no evidence of a direct connection between Osborn and industrial designer Wright, McCann, Whalen, National Capital Region Director Ignatius “Nash” Castro, or NPS Director George B. Hartzog Jr.

A thin link between Elodie Courter Osborn and Wright is known. She began work at MOMA as a volunteer in 1933. She quickly became secretary of circulating exhibitions. In 1935 she was promoted to director of the department, a position she held until 1948. In December 1939 she curated an exhibit at MOMA featuring his work. It's possible they remained friendly over the years, but that is a tenuous link at best.

Although we were not able to personally review the Robert Osborn Papers at the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale University, their archivist could not find any materials that connect Osborn with Summer in the Parks or its creators. Much of the collection is unprocessed, however, and a more detailed review and further research is needed. Until new information is found, the details of how Osborn came to draw the Laughing Tree remains shrouded in mystery.

Parks for All Seasons

In 1970 the success of Summer in the Parks led the National Capital Parks to create a Parks for All Seasons program. It was coordinated by William Whalen, then chief of the Division of Urban and Environmental Activities for National Capital Parks (and a future NPS director). Parks for all Seasons was an effort to turn the popular summer program into one that brought performing arts, graphic arts, sports of all kinds, and people to the parks throughout the year. The NPS History Collection includes a “Fall in the Parks” poster featuring Osborn’s laughing tree logo colored orange and yellow for autumn.

These efforts to bring people to the parks were expanded in the early 1970s to include Richmond National Battlefield in Virginia and the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial in St. Louis. Summer in the Parks and Parks for All Seasons continued until 1976, when the bicentennial shifted priorities and funding elsewhere.

Sources:

--. (Undated). “Elodie Courter.” Accessed May 13, 2024, at https://www.moma.org/interactives/exhibitions/2016/spelunker/constituents/1893/

--. (1928, March 28). “Oshkosh Students Carry Off Honors.” The Oshkosh Northwestern (Oshkosh, Wisconsin), p. 16.

--. (1944, March 18). “Former Oshkosh Man Marries in East.” The Oshkosh Northwestern (Oshkosh, Wisconsin), p. 8.

--. (1945, January 28). “Chicago Institute Shows Cartoons of U.W. Grad.” The Capital Times (Madison, Wisconsin), p. 19.

--. (1949, March 17). “How to Play Golf.” The Oshkosh Northwestern (Oshkosh, Wisconsin), p. 8.

--. (1959, February 24). “Artist, Native of City, Cited by Navy.” Oshkosh Daily Northwestern (Oshkosh, Wisconsin), p. 2.

--. (1969, February 22). “Summer in the Parks—and How it Grew.” Silver City Daily Press (Silver City, New Mexico) p. 21.

--. (1969, July 14). “Ventnor Man Heads Program.” Press of Atlantic City (Atlantic City, New Jersey), p. 22.

Andrews, David. (2010, spring). “Russel Wright, Sowing the Seeds of Environmental Awareness.” Common Ground. National Park Service, Washington, DC, pp. 27-27. Available online at https://www.nps.gov/crps/commonground/spring2010/index.html

Cummings, Paul. (1974, October). Interview with Robert Chesley Osborn conducted October 21, 1974, for the Archives of American Art. Accessed May 12, 2024. Available online at https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-robert-chesley-osborn-13252

Fitzgerald, Moira. (2024, May 7). Pers. Comm. with Nancy Russell, NPS History Collection archivist, regarding the Osborn Papers at the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale University.

Garland-Jackson, Felicia and Shutika, Debra Lattanzi (2020). Summer in the Parks (1968-1976): A Special Ethnohistory Study. National Park Service, Washington, DC.

Gussow, Mel. (1994, December 22). “Robert Osborn Is Dead at 90; Caricaturist and Satirist.” The New York Times (New York, New York), section D, p. 19.

Lanier, Yvonne. (1968, July). “Summer in the Parks.” Trends in Parks & Recreation, Vol. 5, No, 3, pp. 26-28.

Malone, Edward A. (2020, July 15). “’Don’t be a Dilbert’: Transmedia Storytelling as Technical Communication During and After world War II.” Technical Communication, Vol. 66, No. 03, pg. 209.

National Register Nomination for Manitoga, available online at https://npgallery.nps.gov/GetAsset/9d9563bc-c7e8-46b7-b600-348f055fbb74

Orsini, Bette. (1951, November 3). “Cartoonist’s Wife Serves as His Laugh Barometer.” The Richmond News Leader (Richmond, Virginia), p. 18.

Osborn, Robert. (1982). Osborn on Osborn. Tricknor & Fields: New Haven and New York.3)

United States Congress. (1973). “Responses to the Select Subcommittee on Education Regarding Department of the Interior Environmental Education Program.” Hearing before the Select Subcommittee of Education of the Committee on Education and Labor House of Representatives Ninety-Second Congress First Session of Oversight into Administration of the Environmental Quality Education Act of 1970.

Wright, Russel. (1969, April). “Summer in the Parks--1968.” Trends in Parks & Recreation, Vol. 6, No. 2, pp. 1-8. NPS History Collection (HFCA 1645), Harpers Ferry, WV. Available online at http://npshistory.com/newsletters/park_practice/trends/v6n2.pdf