Last updated: March 21, 2025

Article

50 Nifty Finds #46: Feeding the Habit

Most visitors to national parks today know that wild animals are dangerous and should be enjoyed from a distance. For decades, however, the National Park Service (NPS) struggled with preventing visitors from feeding bears even as it encouraged the animals to congregate in areas where visitors could watch them eat garbage generated by park hotels. The situation was unhealthy for bears and downright dangerous for people. Breaking the cycle was a long process of evolving policies, changing human habits, and returning bears to their wild foraging behaviors and traditional foods.

Early Warning Signs

The dangers of feeding bears in national parks were acknowledged by at least 1902. Major John Pitcher of the Sixth Cavalry, acting superintendent of Yellowstone National Park, reported,

The bears are perfectly harmless as long as they are let alone and kept in a perfectly wild state, but when they are fed and petted, as some of them have been in the past, they lose all fear of human beings and are liable to do considerable damage to property and provisions at the various hotel and camp kitchens. They are also liable to frighten tourists by following them with the expectation of being fed.

Pitcher noted that “it is a difficult matter to make some tourists realize that the bear in the park are wild, and that it is a dangerous matter to trifle with them.”

Fear of public injury led him to issue and post a circular on August 8, 1903, prohibiting interfering with bears or any other wild game in the park and forbidding anyone to feed bears except at the regular garbage piles. It wasn’t long before a tourist ignored the rules and was seriously injured, after which the army placed barriers at all the garbage piles and posted signs “indicating the danger of approaching too near bears.” Pitcher noted, “In my opinion, a strict compliance with the requirements of this circular is all that is needed to render the bear in the park perfectly harmless.”

Mixed Messages

Early efforts to condition bears to avoid areas where visitors were couldn’t compete with the lure of food offered by visitors, employees, and concession staff. On April 14, 1914, the acting superintendent of Yellowstone National Park issued instructions that “the feeding, interference with, or molestation of any bear or other wild animal in the park in any way by any person not authorized by the supervisor is prohibited.”

NPS Director Stephen T. Mather noted in his 1917 annual report that,

The black bears hang around the hotels and camps almost constantly, where they are often fed from the hand by people who do not realize that they are taking desperate chances of being injured by playing with fierce wild animals at close quarters. Efforts are made to prevent such feeding, but they are successful only when the full cooperation is had from the hotel or camp help, which is not always the case. In many cases the help, and sometimes even the guards, participate in feeding and playing with the bears. Almost invariably bears so treated eventually become dangerous and have to be killed. Sixteen have been killed during the past season.

Photographs document that consistent cooperation from the concession staff remained elusive for over a decade. Although the bear issues at Yellowstone are the most well known, Yosemite, Sequoia, and other parks also had problems with bear-human interactions around food.

The Danger Line

Mather wrote in 1918 that the bears at Yellowstone were “so fat that they can hardly climb a tree if startled.” Seemingly unaware of their part in the bear problem, visitors complained bitterly when bears tore up the upholstery of their cars searching for food. The next season night guards were stationed in Upper Basin, Lake Outlet, and Canyon to prevent bear damage to cars and camps. Five bears were killed at Lake Outlet to prevent property damage. Despite these concerns, or perhaps in a misguided effort to help alleviate the problem, more formal bear-feeding stations were established at Yellowstone. The 1919 annual report records,

Garbage dumps were established within walking distance of Upper Basin and Canyon where bears of all kinds congregated every evening just before dark, and it was a regular practice for people from the hotels and camps to go to see them. A wire was firmly stretched between the trees and posts to keep people from going beyond the danger line, and a ranger was placed on duty with a rifle to protect them. This is one of the most interesting features of the park to the majority of tourists but requires careful regulation.

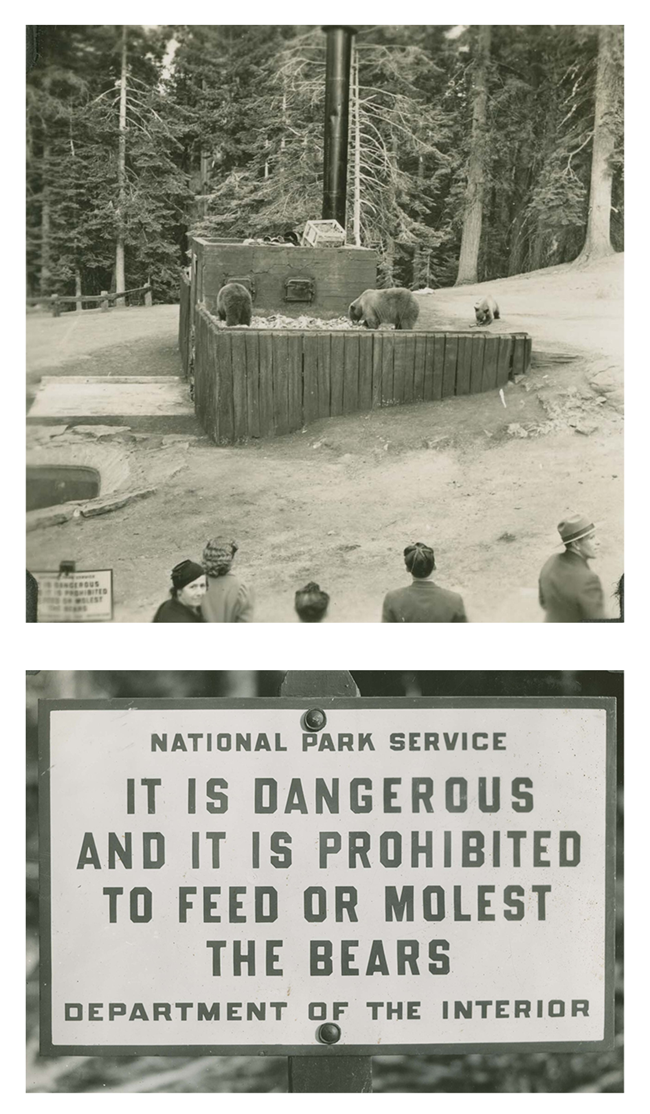

Similar bear-feeding grounds were set up at Yosemite, Sequoia, and other parks over time. One 1923 newspaper account reported that at Yosemite, “Camp Curry guests are finding a new and thrilling diversion in watching wild bears feeding [at the Bear Pit] at night.” They remained popular with bears and tourists throughout the 1920s and 1930s.

Highway Robbery

The 1919 annual report also describes the beginning of what became known as “bear hold ups” at Yellowstone.

Even more interesting than the bear dumps were a few clever bears, among them one or two families consisting of mother and cubs, that frequented the highway between Thumb and Lake Outlet and daily “held up” passing automobiles and begged for food. As a rule, the tourists so held up were willing victims of the robbers, and most of them would risk being tried before the United States commissioner for violation of park regulations which prohibit “approaching, molesting, or feeding the bears” rather than turn a deaf ear to the appeals of the cubs for candy, peanuts, etc. This rule is the most difficult to enforce of all the park rules and regulations.

One infamous bear was named Jesse James by Yellowstone staff. His story was repeated in newspapers across the country. By 1922 newspaper accounts referred to “organized bands of bandit bears” who halted coaches to demand food. If they didn’t get it, they would block the roads to prevent cars moving forward.

The cover of the 1922 Yellowstone brochure features a photograph of members of the US House of Representatives Appropriations Committee tour feeding bears even though the regulations inside noted that “molesting or feeding the bears is prohibited.” Significantly, the 1923 brochure changed the prohibition from feeding to teasing bears.

Glass Houses

The NPS annual reports leave out the fact that many employees and dignitaries also fed the bears, deer, and elk by hand. A 1919 newspaper article quotes Horace Albright, superintendent of Yellowstone and an NPS assistant director, describing a story of a large mule deer following him into the house for food and promptly leaving after Albright offered it a donut.During his visit to the park in 1923, President Warren G. Harding made “friends” with two bears that had been held up a tree by a ranger until his arrival so the event could be photographed.

The garbage dumps, feeding stations, and the “do as I say not as I do” factors weren’t the only mixed messages for the public. One man reported seeing large “Do Not Feed the Bears” signs at Yellowstone in 1929, while the stores in the park sold bags of candy to feed to the bears!

Bears also raided park concession buildings. In fall 1929 bears broke into five of C.A. Hamilton’s stores in Yellowstone. The Park Service Bulletin reported, “They climbed to the highest shelves for jams and jellies, breaking dishes enroute and ripping merchandise to pieces. One big fellow, discovered in his plundering, tucked a sack of sugar under his front leg and went hopping off on three legs.” In 1930 Hamilton built two new structures of reinforced concrete with steel shutters on the windows and doors to protect his investments.

Biting Souvenirs

Yellowstone wasn’t the only park to experience human and bear conflicts. Yosemite, Mount Rainier, and Rocky Mountain national parks had similar problems. In December 1929 Yosemite was gifted a four-month-old puppy named Rinson, son of Hollywood star Rin-Tin-Tin, to condition bears to stay away from campgrounds and other visitor areas in Yosemite Valley. Although his initial efforts were reported to be a success, it’s not clear how long or how well Rinson worked to deter bears from the area.

In 1930 the NPS annual report noted,

Of recent years the bear problem in the larger parks has become serious, due to the feeding of these animals by tourists. The result is that many of them now expect to receive their food in this manner and their depredations in tourist camps have increased. Also, many people are bitten when feeding or pretending to feed the bears. A survey of the entire situation will soon be made to determine the best method of handling the problem.

The next year the annual report noted, “Curiously, visitors even when bitten by bears are more inclined to accept slight injury as a souvenir and happily display it than to complain about the offending bear.” When it came to bears destroying property and breaking into cars or tents, visitors were less tolerant.

More than a decade of artificial feeding led to larger bear populations in some national parks. The Great Depression brought another problem at Yellowstone as the 1932 annual report notes:

Bears were numerous everywhere and were really the main source of grief to the park administration and campers. The bears had increased to such proportions and there was such a shortage of food due to the decrease in business at the hotels and lodges that they became exceedingly bold, particularly around the campgrounds and housekeeping cabin area, doing considerable damage to cars and property belonging to visitors and park operators. Authority therefore was given during the summer for the disposal of surplus bears, both black and grizzly.

Artificial feeding of bears in Yellowstone was creating “an intolerable situation.” Destroying “guilty bears” was the first action but “further changes in policy will be adopted if necessary.” NPS policy change, however, was slow to come.

The Wright Approach

In 1932 the result of the survey mentioned in 1930 was published as Fauna of the National Parks of the United States by George H. Wright, Joseph S. Dixon, and Ben H. Thompson. It notes the serious management problem bears presented to the NPS, which was “obligated to provide for the reasonable safety and comfort of the visiting public.” The report criticized previous NPS approaches:

There would be no logic in destroying the bears and none in keeping the visitors away from them, for that is the very thing which they came to see. Some other solution must be sought, and so far, no program has been entirely successful. It is safe to say that this question will never be solved until a thorough understanding is had of all the causes. Corrective measures are certain to fail until the direct causes of the problems are dealt with. The fallacy of spreading an inviting feast for bears and then “taking them for a ride” to remote sections [of a park] is evident. The bears travel a vicious circle, but obviously it is man who keeps them running on that path.

The report encouraged a data-driven approach to understanding the problem, recommending that the NPS

- record the conditions and actions that lead to every injury people sustained or property damage caused by bears;

- determine if a few bears are responsible for the injuries or property damage or if it is more widespread; and

- study the bears, their populations, ranges, and normal food supplies.

The report recognized that “to educate people of this point of view, for their own safety and pleasure, may take several years, but there seems to be no other course. Concerning the bears themselves, such measures as dogging, trapping, treeing, shooting, and all the rest, are helpful during the stage of transition, but they will never be the ultimate solution. Certain bears which are found to be constant criminals should be disposed of, but such measures should be undertaken only after the facts are definitely known.”

Even as they argued for more study of the problem, Wright, Dixon, and Thompson identified several key strategies that would be instrumental in solving this problem: public education, modifying human behaviors, bear-proofing more structures, and removing food from around human areas.

Changing human behavior and removing the bear-feeding stations, however, would be an uphill battle. In 1932 national park rules and regulations started warning visitors about bears—sort of. A typical example was:

Do not feed the bears from the hand; they will not harm you if not fed at close range. Bear will enter or break into automobiles if food that they can smell is inside. They will also rob your camp of unprotected food supplies.

Note that the admonishment was not to feed the bears “at close range” only. The popularity of bear-feeding stations—for bears and humans—only increased in the 1930s. A new high was set on August 6, 1937, at the Canyon feeding grounds in Yellowstone when 70 grizzly bears came for the “feast.” Park staff estimated that 80,000 people attended the bear feedings during the 1937 season.

Dangerous Animals

Sequoia was the only “bear park” that generally avoided the serious issues presented by bears in other large national parks. It did so by strictly prohibiting the public from feeding bears and responding decisively to “problem bears.” Those that couldn’t be relocated were destroyed.

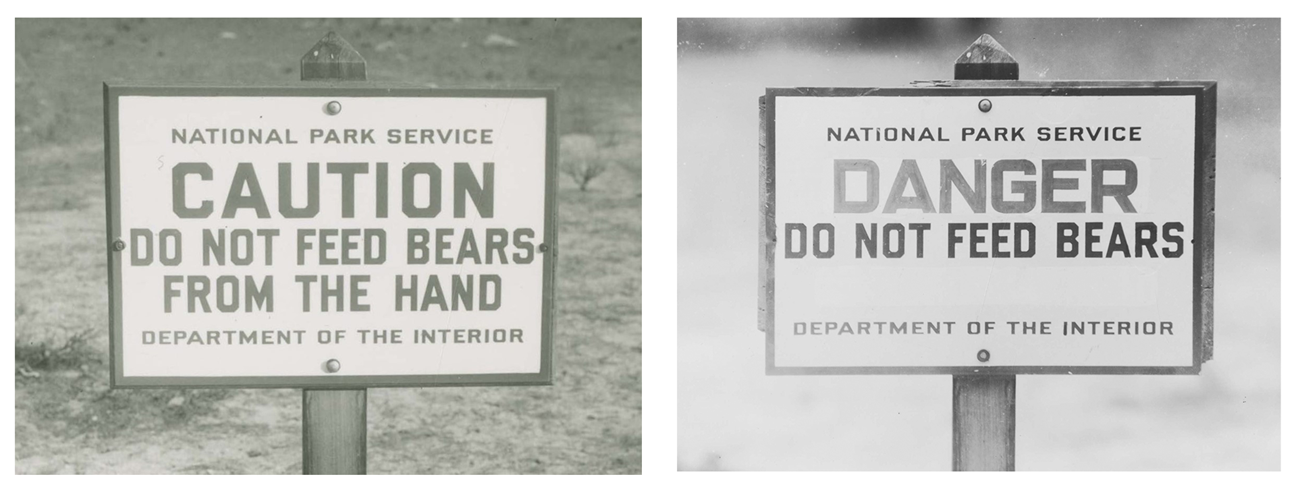

Visitors were informed of the regulation by large, enameled signs that read, “It is dangerous and it is prohibited to feed or molest the bears.” The signs were placed at the Village and, without apparent irony, at Bear Hill (formerly known as Bear Pit), the feeding area near the park’s incinerator where garbage was dumped for the bears so visitors could watch the “bear show.” Lectures at the feedings emphasized the dangers and prohibitions against people feeding bears.

Although Sequoia’s approach avoided the “begging bears” that plagued other parks and the park reported no visitor injuries, 73 bears were destroyed from 1930 through 1937 because they became dangerous to people. Despite that number, 30 to 40 bears still appeared at Sequoia’s daily “bear shows” during the 1937 tourist season. The feeding program ended at the park in 1939.

As the NPS began to reconsider its bear policy, Sequoia was the model for strictly prohibiting public bear feeding.

Evolving Policies

In December 1937 Interior Secretary Harold Ickes signed an order prohibiting feeding, touching, or teasing bears in national parks. Although this applied to individuals, it didn’t stop other NPS bear-feeding “shows.” While the 1938 Yosemite regulations told visitors not to feed the bears, the same brochure directed them to the park’s bear pits where they could watch them feed nightly at 9:30 pm.

There was also a delay in getting the new regulation printed in all park brochures. Crater Lake National Park didn’t include the new language until 1939. Although Mount Rainier National Park’s regulations from 1935 to 1937 referenced not feeding bears by hand, the 1938 regulations became, “Feeding bears in campgrounds and populated areas is prohibited.” This suggested that feeding them in unpopulated areas was acceptable. The park didn’t publish regulations against “feeding, touching, or molesting” bears until 1940.

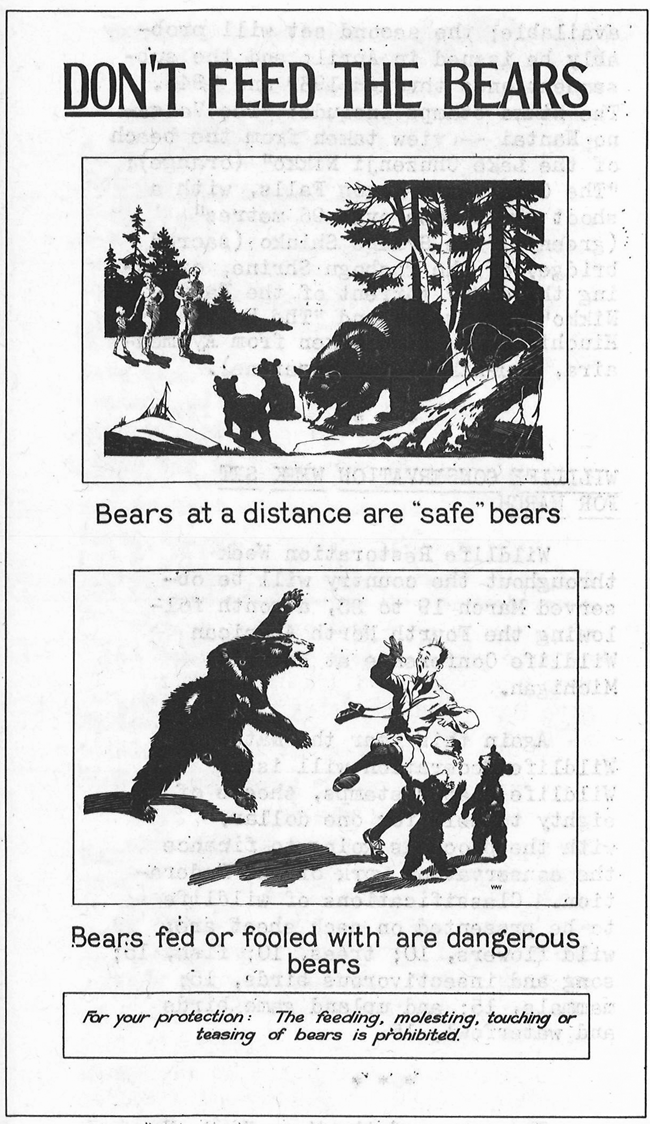

Changing the habits of visitors, park concession operators, and tour companies that advertised bear feeding as a park activity wouldn’t happen overnight. The NPS began an education campaign to reflect the new policy against feeding bears and to discourage visitors from getting too close to them. Park signs were rewritten from cautionary suggestions not to feed bears by hand to outright warnings of the danger and stressing regulations against feeding bears.

Towards the end of 1938 NPS chief wildlife illustrator Walter A. Weber created a poster to express the danger to the public. The poster, titled “Don’t Feed the Bears,” has two panels. The top featured a family staying away from a bear and her two cubs. The caption below reads, “Bears at a distance are ‘safe’ bears.” The lower panel features a bear attacking a man who has gotten between her and her two cubs. The caption reads, “Bears fed or fooled with are dangerous bears.” The bottom of the poster notes, "For your protection: The feeding, molesting, touching, or teasing of bears is prohibited.”

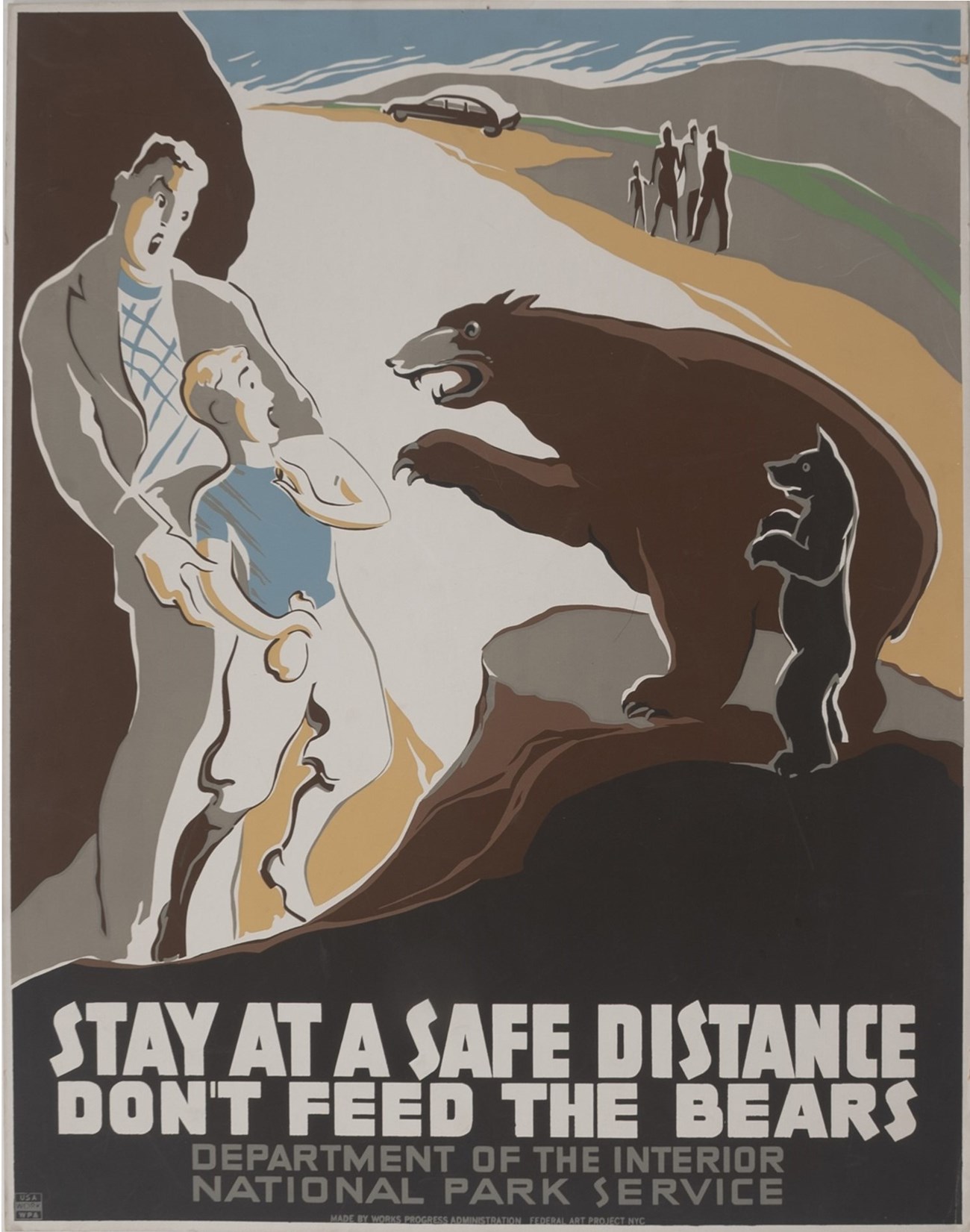

A second poster was created by a Works Progress Administration (WPA) artist in New York around 1939. Some sources list Charles Verschruren as the artist, although it’s unsigned and the style is different from his other work of the period. The silkscreen poster reinforces the “stay at a safe distance” and “don’t feed the bears” messages. Although the mother bear has a less aggressive stance than in Weber’s poster, the threat is conveyed by her outstretched paw and open mouth as the man and boy recoil in fear. The boy carries a bag of food as the bear cub begs for treats, and a family walks away in the distance.

NPS Director Newton B. Drury noted in the 1942 annual report that “efforts were made to impress the public with the necessity of treating bears as wild animals.” Despite this, one person died from a bear attack at Yellowstone that year. Drury describes it as the first death by bear attack at the park, although there had been many maulings. To control the population and to eliminate bears deemed dangerous to humans, 87 were killed at Yellowstone, Yosemite, and Crater Lake in 1942.

Grin and Bear It

In 1940 the NPS got support for its policy change from an unlikely source. At the request of Superintendent Edmund Rogers, Warner Bros. Studios producer Leon Schlesinger allowed Yellowstone National Park to use stills from his Merrie Melodie cartoon film called “Cross Country Detour.” In the first frame, a bear sits next to a tree with a “Danger Do Not Feed the Bears” sign nailed to it. A tourist approaches and reads the sign. In the next frame, the tourist offers the bear a sandwich. Next the bear pummels the visitor repeatedly over the head. Finally the bear pulls the sign off the tree, points to it, and says, “Can’t you read!”

The black and white cartoon was copied and supplied to each ranger at Yellowstone National Park. “When a ranger sees a visitor who is feeding a bear or looks as if he might be ready to do so, the ranger slips one of these reproductions out of his pocket and hands it to the ‘law breaker.’” Rogers reported that the humorous approach met with success. In fact, the cartoon was turned into a color poster four years later.

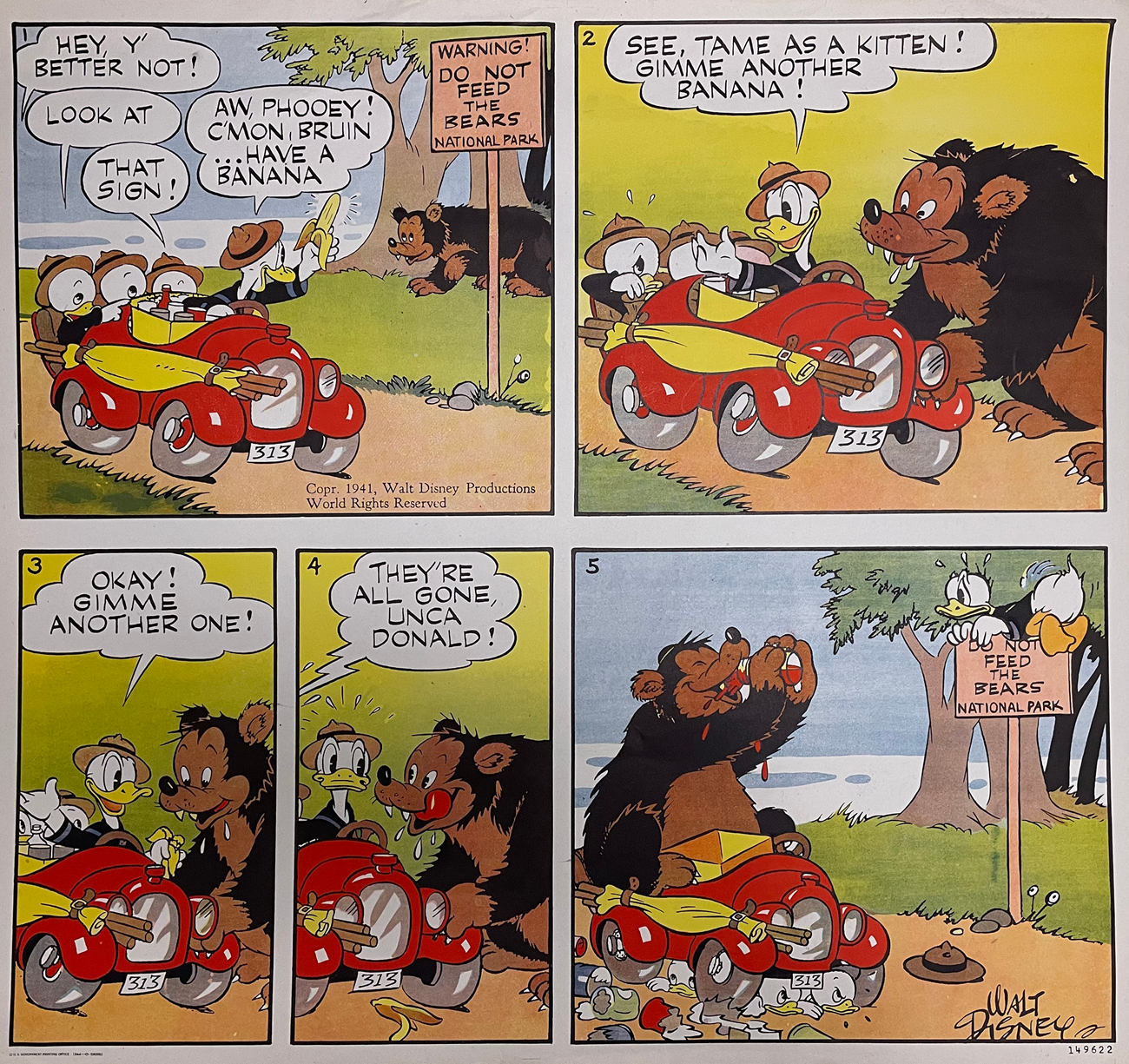

The NPS also issued a Donald Duck bear warning poster in 1944. It is a reproduction of a newspaper cartoon strip by Walt Disney. The original cartoon featured Donald and his three nephews driving into Sequoia National Park. Ignoring the “Do Not Feed the Bears” sign, Donald offers a banana to a bear. Claiming it was “tame as a kitten,” Donald gave him another. When Donald runs out of bananas, the bear proceeds to take everything, chasing Donald and the family out of their car. After it ran in newspapers, the NPS wrote to Disney and asked permission to use the cartoon and to change the sign so that it would be applicable to all the parks having bear problems. The Disney Studio very kindly agreed. It’s not known how many of either cartoon poster was printed.

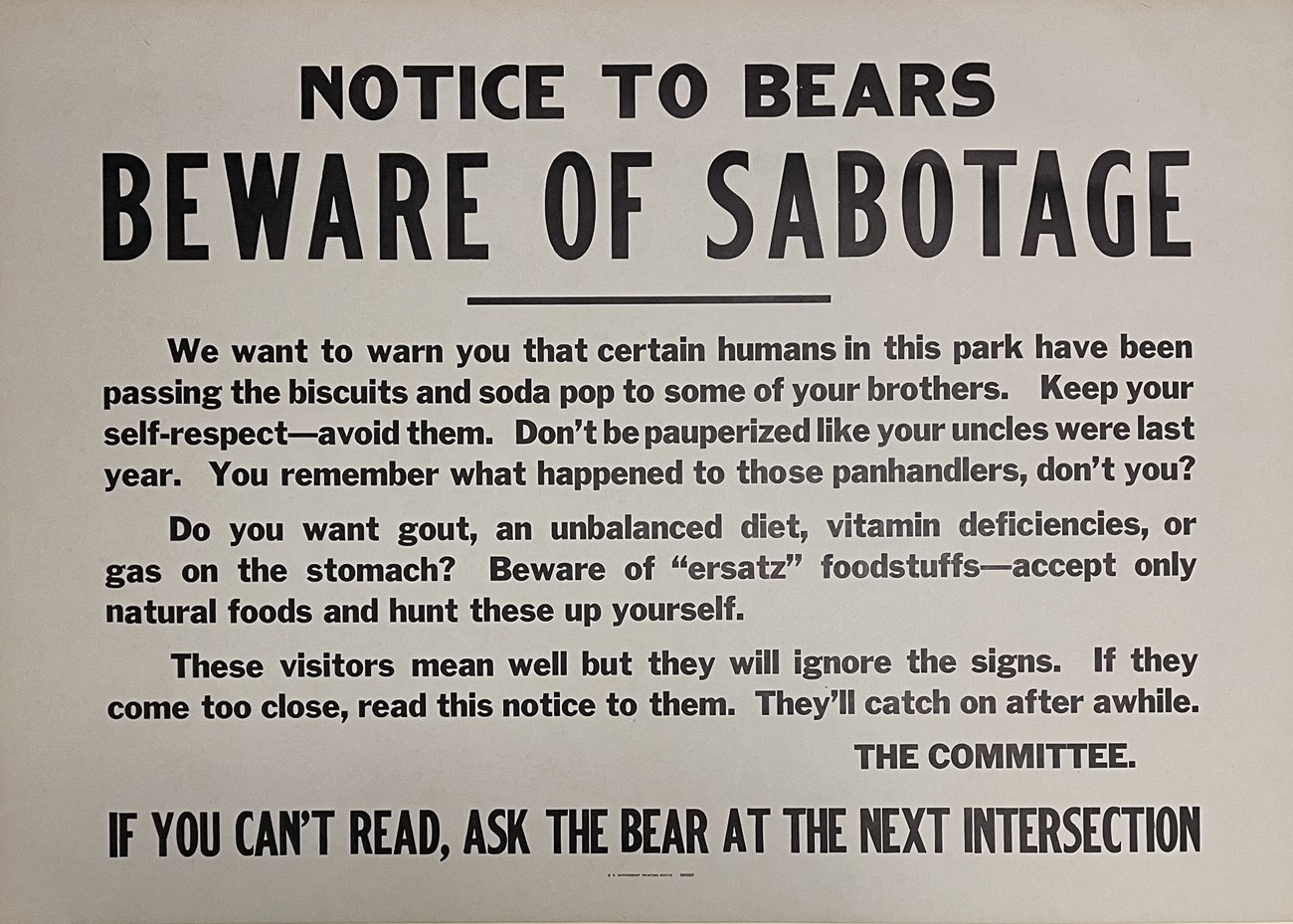

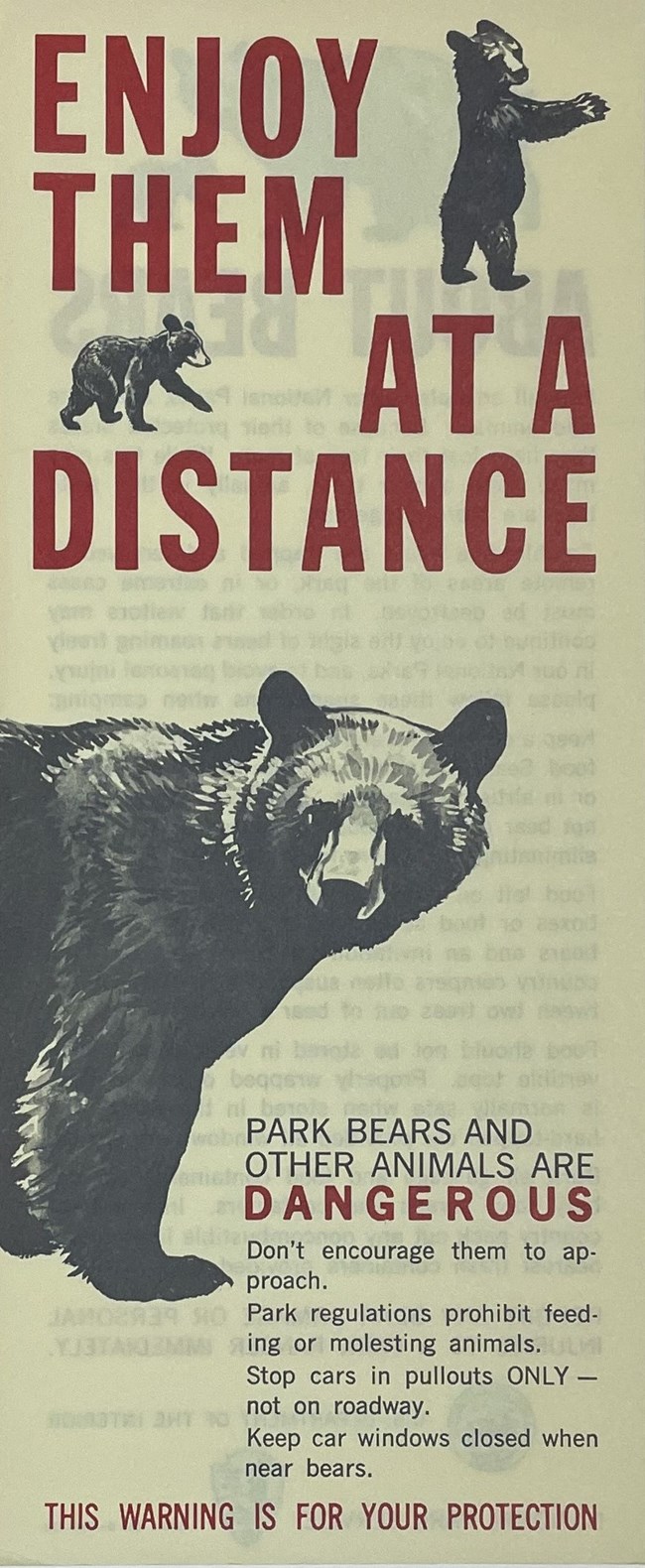

Victor H. Cahalane, acting chief naturalist, described both cartoon posters to the House Select Committee on Conservation of Wildlife Resources in November 1944. He went on to tell the committee about two other large posters created by the NPS. He described one posters as "an attempt to put over to the public the conception that bears should be enjoyed but avoided, as least at close range; also to try to tell park visitors who are interested in the welfare of the animals that the junk—pop, sandwiches, and food, so-called—is actually detrimental to the bears."

The fourth poster is an attempt to put over to the public the conception that bears should be enjoyed but avoided, as least at close range; also to try to tell park visitors who are interested in the welfare of the animals that the junk—pop, sandwiches, and food, so-called—is actually detrimental to the bears. This is done in an indirect way by a poster that reads,

Notice to bears. Beware of sabotage. We want to warn you that certain humans in this park have been passing biscuits and soda pop to some of your brothers. Keep your self-respect. Avoid them. Don’t be pauperized like your uncles were last year. You remember what happened to those panhandlers, don’t you? Do you want gout, an unbalanced diet, vitamin deficiency, and gas on the stomach? Beware of “ersatz” foodstuffs. Use only natural foods and hunt these up yourselves. These visitors mean well but they will ignore the signs. If they come too close, read this notice to them. They will catch on after a while.

The poster is signed “The Committee” with a final note: “If you can’t read, ask the bear at the next intersection.”

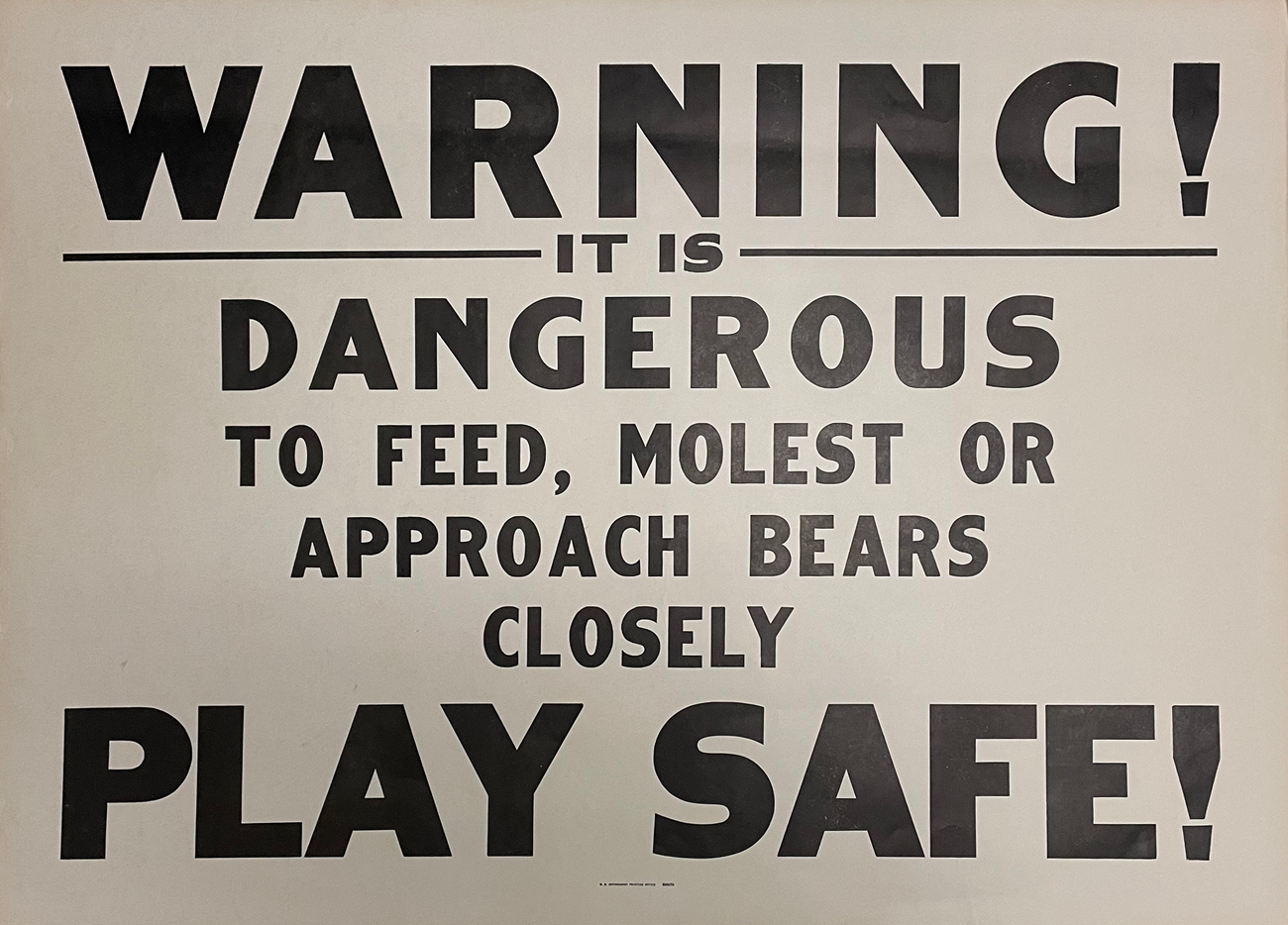

Where humor failed, a fourth poster was created with a simple but blunt “Warning! It is dangerous to feed, molest, or approach bears closely. Play safe!”

Cahalane noted,

The problem of troublesome bears in Yellowstone and Yosemite national parks has been rather considerably relieved through educational programs designed to discourage the feeding and petting and other undue intimacy with bears, and by determined action in dispersing or destroying the bears when other means failed. Of course, a marked decline in the number of park visitors also played a part in improving the situation.

Smarter than the Average Bear?

Despite Cahalane’s upbeat message to the committee, the poster campaign had limited success. Drury’s frustration with the issue can be heard in his 1946 report:

It is difficult to get visitors to parks to realize that park regulations are designed to further their safety, rather than impose some irksome restrictions on their freedom of action, though it is probably that more thought and effort need to be expended in educating visitors not only as to what the regulations are but as to the reasons that make them necessary. Probably nothing better exemplifies this difficulty than the regulations which forbid the feeding of wild animals. It hardly seems possible for anyone who can read to visit Yellowstone or Yosemite national parks without being aware of the prohibition against feeding the bears. Yet year after year, hundreds of visitors insist on taking chances by handing these genuinely wild animals tidbits of food, and every year has its record of serious and even occasional fatal injuries to those who indulge in the practice. The Service is constantly searching for new methods of impressing upon the public the hazards of familiarity with park wildlife, as well as the injurious effects upon the wildlife itself of unsuitable diet and of dependence upon “panhandling” for food.

The problem persisted. Drury noted in his fiscal year 1949 report that black bears presented a dangerous problem in Yellowstone, Glacier, Yosemite, Sequoia, and Great Smoky Mountains national parks.

Despite repeated warnings, a small minority of visitors persist in feeding these animals. The number of injuries is remarkably small, but traffic is often snarled along heavily traveled roads and accidents result from the congregation of visitors around “roadside” bears. Their appetites for artificial foods whetted by promiscuous feeding, some of these animals make serious nuisances of themselves by breaking into buildings and automobiles in search of food.

During summer 1951, the NPS handed out over one million red-and-black, briefly worded printed warnings to visitors, trying to persuade them to comply with regulations prohibiting feeding, molesting, or teasing bears. Despite this, 38 people were injured by bears at Yellowstone alone. Hand-feeding bears was the cause of injury in most of those cases. As a result, 47 “troublesome” bears had to be destroyed. In 1952 the NPS extended the prohibition against feeding, molesting, or harassing the bears to deer, moose, bison, mountain sheep, elk, and antelope.

Throughout the 1950s bears continued to bite or scratch visitors who refused to obey the rules. Property damage also continued as people failed to properly store food while in the parks.

In 1960 the NPS initiated a bear-management policy to reduce visitor injuries and return bears to their natural habitats. By 1962 the bear-management programs had significantly reduced injuries and property damage to visitors.

It took decades to return bears to their natural state and to educate visitors about the dangers of feeding or approaching bears and other wildlife.

Although most visitors today understand the importance of keeping wild animals wild, practice good food storage methods, and understand just how dangerous the activities depicted in these historic photographs were, a small number of visitors continue to get too close to animals like bison, deer, or elk in national parks. Please always “Enjoy Them at a Distance.”

Sources

--. (1919, December 5). “Deer and Bear Are Tame Out There.” The Chanute Daily News (Chanute, Kansas), p. 8.--. (1921, August 1). “Famous ‘Hold Up’ Bear on The Job.” Greenville News (Greenville, North Carolina), p. 1.

--. (1922, February 12). “Bear Playful Hold-up Man.” The Duncan Daily Banner (Duncan, Oklahoma), p. 8.

--. (1922, March 5). “Bears in Yellowstone Park ‘Hold Up’ Tourists.” St. Louis Globe-Democrat (St. Louis, Missouri), p. 32.

--. (1923, August). “Presidential Visit.” Park Service Bulletin, No. 19, pp. 1-2. Assembled Historic Records of the NPS (HFCA 1645), NPS History Collection, Harpers Ferry, WV.

--. (1923, September 6). “Yosemite Guests Watch Bears Eat.” Bakersfield Morning Echo (Bakersfield, California), p. 7.

--. (1929, December 14). “Rin-Tin-Tin’s Son Gets Job Herding Bruins.” Stockton Evening and Sunday Record (Stockton, California), p. 29.

--. (1930, January 1). “New Yellowstone Stores Built from Concrete to Protect from Bears.” Park Service Bulletin, No. 49, p. 8. Assembled Historic Records of the NPS (HFCA 1645), NPS History Collection, Harpers Ferry, WV. Available online at http://npshistory.com/newsletters/courier/bulletin/49.pdf

--. (1930, December). “Man Does Not Mind Bear Bite.” Park Service Bulletin, No. 53, p. 9. Assembled Historic Records of the NPS (HFCA 1645), NPS History Collection, Harpers Ferry, WV. Available online at http://npshistory.com/newsletters/courier/bulletin/53.pdf

--. (1932, January). “Bear Disrupts Superintendent’s Christmas Dinner at Rainier Park.” Park Service Bulletin, Vol. II, No. 1, p. 9. Assembled Historic Records of the NPS (HFCA 1645), NPS History Collection, Harpers Ferry, WV. Available online at http://npshistory.com/newsletters/courier/bulletin/v2n1.pdf

--. (1937, October). “New Attendance Record for Bear Feeding Grounds.” Park Service Bulletin, Vol. VII, No. 1, pp. 7-8. Assembled Historic Records of the NPS (HFCA 1645), NPS History Collection, Harpers Ferry, WV. Available online at http://npshistory.com/newsletters/courier/bulletin/v7n9.pdf

--. (1938, March-April). “Inconsistent Bear Policies.” Park Service Bulletin, Vol. VIII, No. 2, pp. 15-16. Assembled Historic Records of the NPS (HFCA 1645), NPS History Collection, Harpers Ferry, WV. Available online at http://npshistory.com/newsletters/courier/bulletin/v8n2.pdf

--. (1939, January-February). “Don’t Feed the Bears Poster.” Park Service Bulletin, Vol. IX, No. 1, p. 8. Assembled Historic Records of the NPS (HFCA 1645), NPS History Collection, Harpers Ferry, WV. Available online at http://npshistory.com/newsletters/courier/bulletin/v9n1.pdf

--. (1939, June). “Bears are Bears.” Park Service Bulletin, Vol. IX, No. 5, p. 7. Assembled Historic Records of the NPS (HFCA 1645), NPS History Collection, Harpers Ferry, WV. Available online at http://npshistory.com/newsletters/courier/bulletin/v9n5.pdf

--. (1940, July-August). “Bear Enforces Park Regulation in ‘Merri Melodie’ Cartoon.” Park Service Bulletin, p. 8. Assembled Historic Records of the NPS (HFCA 1645), NPS History Collection, Harpers Ferry, WV. Available online at http://npshistory.com/newsletters/courier/bulletin/v10n4.pdf

National Park Service. (1916). Annual Report of the Superintendent of National Park to the Secretary of the Interior for the Fiscal Year ended June 30, 1916. Washington, DC. NPS History Collection (HFCA 1645), Harpers Ferry, WV.

National Park Service. (1917). Annual Report of the Superintendent of National Park to the Secretary of the Interior for the Fiscal Year ended June 30, 1917. Washington, DC. NPS History Collection (HFCA 1645), Harpers Ferry, WV.

National Park Service. (1918). Annual Report of the Superintendent of National Park to the Secretary of the Interior for the Fiscal Year ended June 30, 1918. Washington, DC. NPS History Collection (HFCA 1645), Harpers Ferry, WV.

National Park Service. (1919, October). “Wild Animals.” National Park Service News, No. 5, p. 16. NPS History Collection (HFCA 1645), Harpers Ferry, WV. Available online at http://npshistory.com/newsletters/courier/news/5.pdf

National Park Service. (1930). Annual Report of the Director of the National Park Service to the Secretary of the Interior for the Fiscal Year ended June 30, 1930. Washington, DC. NPS History Collection (HFCA 1645), Harpers Ferry, WV.

National Park Service. (1931). Annual Report of the Director of the National Park Service to the Secretary of the Interior for the Fiscal Year ended June 30, 1931. Washington, DC.

National Park Service. (1932). Annual Report of the Director of the National Park Service to the Secretary of the Interior for the Fiscal Year ended June 30, 1932. Washington, DC. NPS History Collection (HFCA 1645), Harpers Ferry, WV.

National Park Service. (1943). Annual Report of the Director of the National Park Service to the Secretary of the Interior for the Fiscal Year ended June 30, 1943. Washington, DC. NPS History Collection (HFCA 1645), Harpers Ferry, WV.

National Park Service. (1946). Annual Report of the Director of the National Park Service to the Secretary of the Interior for the Fiscal Year ended June 30, 1946. Washington, DC. NPS History Collection (HFCA 1645), Harpers Ferry, WV.

National Park Service. (1949). Annual Report of the Director of the National Park Service to the Secretary of the Interior for the Fiscal Year ended June 30, 1949. Washington, DC. NPS History Collection (HFCA 1645), Harpers Ferry, WV.

National Park Service. (1952). Annual Report of the Director of the National Park Service to the Secretary of the Interior for the Fiscal Year ended June 30, 1952. Washington, DC. NPS History Collection (HFCA 1645), Harpers Ferry, WV.

National Park Service. (1958). Annual Report of the Director of the National Park Service to the Secretary of the Interior for the Fiscal Year ended June 30, 1958. Washington, DC. NPS History Collection (HFCA 1645), Harpers Ferry, WV.

National Park Service. (1960). Annual Report of the Director of the National Park Service to the Secretary of the Interior for the Fiscal Year ended June 30, 1960. Washington, DC. NPS History Collection (HFCA 1645), Harpers Ferry, WV.

National Park Service. (1962). Annual Report 1962. Washington, DC. NPS History Collection (HFCA 1645), Harpers Ferry, WV.

Nethery, Ruby. (1922, August 21). “’Jesse James’ Robber Bear, Hold Up Tourists for Peanuts.” The Norman Transcript (Norman, Oklahoma), p. 5.

United States Government. (1945). Hearing minutes from the US House of Representative Committee of Wildlife Resources, November 17, 27, 28, and 29, 1944. Government Printing Office: Washington, DC. Available online at https://www.google.com/books/edition/Conservation_of_Wildlife/W8YtAAAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=Conservation+of+Wildlife+Hearings+1944&printsec=frontcover

Wright, George M., Dixon, Joseph S., and Thompson, Ben H. (1932). Fauna of the National Parks of the United States. Government Printing Office: Washington, DC. NPS History Collection (HFCA 1645), Harpers Ferry, WV. Available online at http://npshistory.com/series/fauna/1.pdf

Tags

- glacier national park

- great smoky mountains national park

- mount rainier national park

- rocky mountain national park

- sequoia & kings canyon national parks

- yellowstone national park

- yosemite national park

- nps history

- nps history collection

- hfc

- bear

- bears

- feeding

- bear management

- bear mauling

- bear safety

- bear attacks

- bear viewing

- art

- cartoon

- historical cartoon

- poster

- posters