Last updated: October 30, 2023

Article

50 Nifty Finds #35: On the Same Track

America’s national parks—and the National Park Service (NPS) that manages them—are known around the world today. In the early 1900s, however, few people had visited them, they were managed individually, and they were at risk from development pressures. Many believed that to ensure their protection, a new government bureau within the Department of the Interior (DOI) was needed. Stephen Tyng Mather was hired to build public and political support for a new bureau for national parks. To implement his vision, Mather called on an industry with a track record with western national parks—the nation’s railroad companies.

National Parks Promoter

Mather was born in San Francisco, California on July 4, 1867. After graduating from the University of California-Berkeley in 1887, he moved to New York where he got a job as a reporter for the New York Sun. While there, he met reporter Robert Sterling Yard, who would also play an important role in the early history of the NPS.

After 1893 Mather became an advertising and sales-promotion manager for the Pacific Coast Borax Company in New York, creating marketing campaigns that promoted borax for use in everything from cleaning agents and laundry detergents to pottery and beauty products. He wrote letters for women’s magazines and, through friends in the newspaper business, planted stories about the usefulness of borax, all to support his goal of “a package of borax on every kitchen shelf.” He created the brand name “20 Mule Team Borax,” which can still be found in the detergent aisle of grocery stores today. In 1904 he cofounded the Thorkildsen-Mather Borax Company. Within a decade, he was a millionaire.

Secretary of the Interior Franklin K. Lane hired Mather to build public and political support for a new bureau for national parks and monuments. He was sworn in as an assistant to Lane on January 21, 1915. Mather had money and talent to bring to the issues of national parks, and he was generous towards this cause. He was also tireless, driven, likeable, and persuasive. As an avid outdoorsman, he believed in his mission. Mather, who struggled throughout his adult life with mental illness in the form of bipolar disorder, had spent time with the Sierra Club in the High Sierras in California, and often took solace in nature.

Mather also understood the power of a great advertising campaign, and he brought his experience and contacts with him to Washington, DC. He knew that creating a national parks bureau required popular support, which would encourage business and political support. Although advertising would be important, developing visitor services was crucial to bringing people to the parks and building grassroots support for park protection. To accomplish both, Mather turned to the nation’s railroad companies.

Railroad Romanticism

Although the transcontinental railroad was completed in 1869, tourism in the West was limited by a lack of hotels and other amenities and organized activities. Most of those who did travel there only saw it through the windows of their train cars on their way to resort hotels. Many wealthy Americans preferred to go to Europe where travel was easier and more luxurious. It wasn’t until the 1890s that railroad companies began building scenic railroad lines, short lines, and branches to make western scenery in general—and some national parks in particular—into tourist destinations.

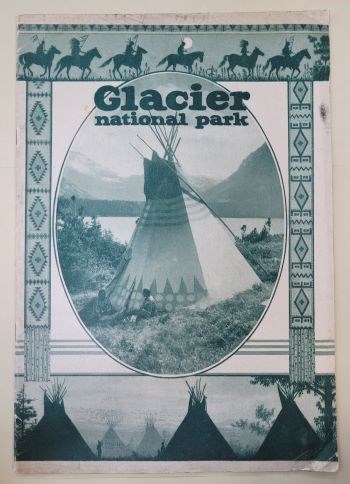

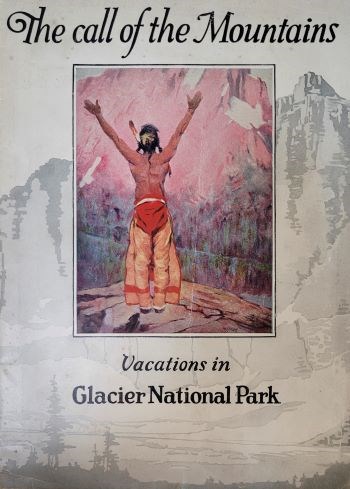

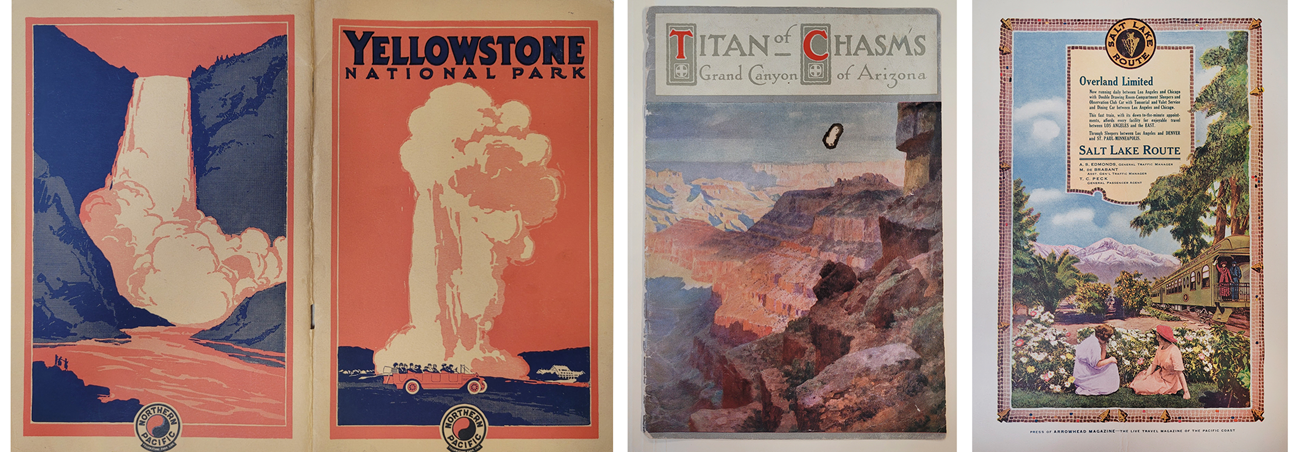

To advertise their services and encourage people to visit the western national parks, early railroad companies created print marketing campaigns including posters, brochures, and leaflets. The NPS History Collection includes examples of this early advertising. The bold, colorful imagery and romantic language evoked a yearning for a quickly vanishing western frontier.

Many brochures used a sense of national and cultural identity to encourage Americans to see beyond the sprawling cities and factory towns to the beautiful landscapes, stunning geology, and unique plants and animals found in the West. National parks weren't just something every American should know about before it was gone. Railroads encouraged the idea that Americans were the “legitimate heirs” of this “true America,” the next step of Manifest Destiny.

Native Americans and their ways of life featured prominently in the romantic promotion of the “vanishing West”—even as they were being removed from their lands and forced into the predominantly white Euro-American culture. Railroad publicity materials were widely distributed, and their imagery featured stereotypes about Native Americans, many of which remain today. The Great Northern Railway in particular relied on Native American imagery to sell its trips to Glacier National Park. It and the Fred Harvey Company, a partner of the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad (AT&SF), paid Native Americans at Glacier and Grand Canyon, respectively, to live in the parks, greet visitors, and entertain them with cultural demonstrations.

Rails to Trails

The history of railroad companies and national parks is complex. There were more companies serving parks than can be discussed here. Some companies built railroads or spur lines specifically to get tourists to national parks. Examples for western parks include:

-

Glacier National Park (Great Northern Railroad, completed in 1891)

-

Grand Canyon National Monument [national park beginning in 1919], South Rim (Grand Canyon Railway, a subsidiary of the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad, completed in 1901)

-

Yellowstone National Park, North Entrance (Northern Pacific Railroad, completed in 1883)

-

Yellowstone National Park, East Entrance (Chicago, Burlington, & Quincy Railroad, completed in 1901)

-

Yellowstone National Park, West Entrance (Union Pacific Railroad, completed in 1907)

-

Yellowstone National Park, South Entrance (Chicago and Northwestern Railroad, completed in 1907)

- Yellowstone National Park, Northwest Entrance (Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul, and Pennsylvania Railroad, completed 1927)

- Yosemite National Park (Yosemite Valley Railroad, completed in 1907)

Other railway lines were built for freight rather than tourism, but companies increased passenger service—and park promotions—to take advantage of their proximity to national parks. Some railroad companies also operated auto stages to take visitors to national parks from the nearest train station.

See America First

Many businesses, boosters, and politicians recognized that travel to the West needed to be easier, cheaper, and more entertaining. In the 1880s and 1890s, wealthy Americans spent their money traveling to Europe, which was considered more sophisticated, or visiting resorts in the eastern United States. The transportation, lodging, and dining facilities to entice rich tourists didn’t exist in most of the West.

The See America First Conference, held in 1906 in Salt Lake City, Utah, was a movement to “make better citizens of tens of thousands of Americans who are now living in ignorance of their own land.” The rallying cry of “See Europe if you must, but See America First” brought together western businesses, civic leaders, and railroad companies to create attractions; build roads, hotels, and restaurants; and advertise all there was to see and do. Scenery was an asset, as was the romantic imagery of the West. The publicity departments of railroad companies were key players in selling the vision and getting customers to go West. It was also an effort to cement Western history and identity as part of the national American culture.

Although these early efforts never really took off, the Great Northern Railway later tied their publicity campaign to the broader “See America First” message. Picking up the earlier idea, the railroad company even tried unsuccessfully to copyright the phrase in 1912 to ensure its connection to the company and Glacier National Park. The phrase captured the public’s imagination and was helped by World War I, which prevented wealthy Americans from traveling to Europe during the war and its immediate aftermath.

A Hollow Enjoyment

Early railroad companies also created—and promoted—some of the iconic historic lodges visitors still enjoy in national parks today. The Northern Pacific Railroad provided funding to the Yellowstone Park Association to build Old Faithful Inn in 1904. Charles Whittlesey, chief architect for the AT&SF designed the El Tovar Hotel in 1905 on the South Rim of the Grand Canyon. It was operated by the Fred Harvey Company in conjunction with the Santa Fe Railway. The Great Northern Railway’s Many Glacier Hotel opened in Glacier National Park in 1915.

Despite these and other substantial investments, lack of amenities was an obstacle to increasing tourism to national parks. In 1915 Mark Daniels, superintendent of national parks, noted that scenery alone—no matter how grand—wouldn’t entice people to come if there was nowhere for them to stay. Mather also recognized this problem, writing “Scenery is a hollow enjoyment to a tourist who sets out in the morning after an indigestible breakfast and a fitful sleep on an impossible bed.” For more than a decade, the railroad companies had been put upon to address this need.

The reluctance the railroad companies felt about operating hotels was plainly addressed by Louis W. Hill, president of the Great Northern Railway, at the first National Parks Conference at Yellowstone in 1911. He stated,

We do not wish to go into the hotel business. We wish to get out of it and confine ourselves strictly to the business of getting people there just as soon as we can. But it is difficult to get capital interested in this kind of pioneer work. With the cooperation and assistance of the government, we hope within two or three years to get financial people interested in the park and then we can get out and attend to railroading.

Despite their reluctance, Mather continued to push the railroad companies to provide these kinds of services. In the 1920s, he got Union Pacific to open the North Rim of Grand Canyon and Zion, Bryce Canyon, and Cedar Breaks in Utah to railroad traffic. The company built a branch of their subsidiary Los Angeles & Salt Lake Railroad from Lund to Cedar City, Utah, where it purchased and operated a hotel and a line of auto stages to those parks. Union Pacific also established the Utah Parks Company to build hotels and lodges at the North Rim of Grand Canyon within the park, and lodges at Zion and Bryce Canyon National Parks.

As long as the railroad companies had these interests, they needed to advertise and promote their hotels and other services for people once they arrived in the parks.

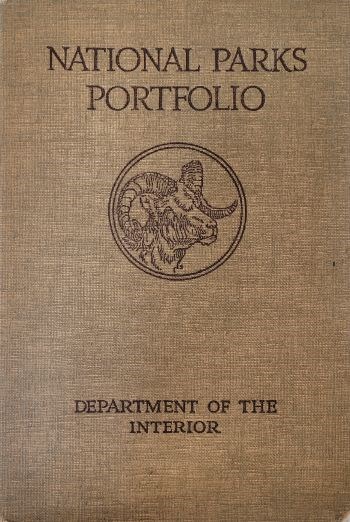

National Parks Portfolio

Mather decided a book was needed to increase park tourism and encourage popular and political support for a parks bureau to manage the national parks and monuments. Written by his old friend Yard, National Parks Portfolio was a series of nine pamphlets that presented “the people of this country a panorama of our principal national parks set side by side for their study and comparison,” adding that “each park will be found highly individual. The whole will be a revelation.” It combined romantic and patriotic text with lots of photographs of splendid scenery and people enjoying the parks as “inspiring playgrounds.” The first edition was issued in June 1916, two months before the NPS was created. It included a pamphlet on the Grand Canyon, which Mather hoped to get from the Department of Agriculture.

Unlike Glimpses of Our National Parks, a booklet series printed by the DOI for the public, Portfolio was described by Mather as a “high-class booklet” with “a different character entirely.” Publishing 275,000 copies cost $48,000, much more than the government would authorize. Mather provided the first $5,000 to cover the cost of creating the image plates. He got 17 western railroad companies to provide the rest. Mather and Yard intended to use the Portfolio to reach a handpicked elite of American society, hoping to create a top-down approach to national park travel. The mailing list was created from the rolls of men’s and women’s clubs, professional societies, universities, social registers, and chambers of commerce. The Portfolio was sent for free to those judged most likely to be excited enough by it to visit national parks and then spread the word to others. Mather also made sure a copy of the Portfolio was given to every member of Congress.

For their investments, railroad companies saw their transportation services mentioned in the pamphlets. A map showed how to reach the western national parks, together with directions to “apply to your local railway ticket office, or to any excursion agency, or write to the passenger departments of the railroads.” A list of the railroads and their addresses was provided. Given their large investment, railroad executives were probably unhappy to read the introduction by Secretary Lane, which called on Congress to provide more money to build roads in parks.

The Portfolio was updated and expanded after the NPS was established on August 25, 1916. The 1917 edition was one of the first official publications of the new NPS. It was sold through the Government Printing Office. Many western railroad companies further helped publicize national parks in 1917 by assisting with a new lantern-slide service. These glass slides were often hand colored and accompanied lectures about the park's history, visitor services, and scenic beauty. Beginning with the third edition published in 1921, the Portfolio became a standard bound book. It was updated periodically until the early 1930s when budget cuts prevented more editions.

A Golden Age Ends

Although there were fears that World War I would reduce visits to parks in 1917, numbers increased. By the summer 1917 season, all parks were open to private cars, providing other options for visitors. One of the ways railroads responded was to promote new “park-to-park” trips. Most railroads maintained their ridership that year, and some even saw increases.

Although the 1917 tourist season was a big success, in December that year the United States nationalized the railroads to support the war effort. When armistice was declared on November 11, 1918, the United States Railroad Administration turned its attention to publicizing national parks. In the first nine months of 1919, it printed or distributed at least 2.5 million booklets, circulars, and leaflets promoting travel to national parks and presented lectures, lantern slides, and films to over 115,000 people.

The nation’s railroad infrastructure was returned to the private companies on March 1, 1920. Mather once again convinced the companies to invest in publicizing the parks. He also got them to reduce their rates, tighten their schedules, and improve service. The results were “package tours” that wrapped the major expenses of a trip into the ticket price. Some railroads created their own bureaus to promote travel to national parks.

Ultimately, however, the railroads couldn’t compete as private car ownership increased. From 1914 through 1920 the number of private cars increased sixfold. Beginning in 1919, cars could be bought on installment, further rapidly increasing their numbers. Amenities like free public campgrounds and improving roads provided further competition to the railroads. While discrimination continued to limit travel for people of color, more white tourists could afford to visit national parks in the 1920s to 1950s.

Although railroads continue to bring passengers to (or near) national parks today, post-World War II prosperity, creation of the interstate highway system, and Americans’ love affair with their cars ended the golden age of railroad advertising for national parks.

Sources:

-- (1999). “Historic Railroads: A Living Legacy.” Cultural Resource Management, Vol. 22, No. 10, pp. 4-6, 15-21, and 24-31. Accessed August 24, 2023, at http://npshistory.com/newsletters/crm/crm-v22n10.pdf.

-- (2022, December 27). “50 Nifty Finds #4: Getting in the Zone.” National Park Service. Accessed August 25, 2023, at https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/50-nifty-finds-4-getting-in-the-zone.htm.

-- “All Set for the West: Railroads and the National Parks.” Union Pacific Railroad Museum. Accessed August 16, 2023, at https://www.uprrmuseum.org/uprrm/exhibits/traveling/national-parks/index.htm.

Butler, William B. (2007). Railroads in the National Parks. Accessed August 24, 2023, at https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/nps/railroads.pdf.

Cavanaugh, Ray. (2016, August 25). “Why the National Park Service is Necessary, at Told in 1916.” TIME. Accessed August 24, 2023, at https://time.com/4445571/national-parks-portfolio/.

Chappell, Gordon. (1976). “Railroad at the Rim: The Origin and Growth of Grand Canyon Village.” The Journal of Arizona History, Vol. 17, No. 1, Spring 1976.

Clayton, John. (2016, July 25). “Stephen Mather and the Founding of the National Park Service: 100 Years of Brand, Strategy, and Selfless Service.” Magic Magazine. Accessed August 24, 2023, at http://montanamagazines.com/magic/stephen-mather-and-the-founding-of-the-national-park-service-100-years-of-brand-strategy/article_979db38a-e672-5e92-86ae-a99bf50f0598.html.

Einberger, Scott. (2018, March 27). “The Triumph of Manic Mather.” Psychology Today. Accessed on October 28, 2023, at https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/the-guest-room/201803/the-triumph-manic-mather

Henderson, James D. (1966). “Meals by Fred Harvey.” Arizona and the West: A Quarterly Journal of History, Vol. 8, No. 4, Winter 1966. The University of Arizona Press, Tucson, AZ.

National Park Service. (1917). Report of the Director of the National Park Service to the Secretary of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1917. NPS History Collection (HFCA 1646), Harpers Ferry, WV. Available digitally at http://npshistory.com/publications/annual_reports/director/1917.pdf

National Park Service. (1920). Report of the Director of the National Park Service to the Secretary of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1920, and the Travel Season 1920. NPS History Collection (HFCA 1646), Harpers Ferry, WV. Available digitally at http://npshistory.com/publications/annual_reports/director/1920.pdf

Shaffer, Marguerite S. (2001). See America First: Tourism and National Identity, 1880-1940. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.

Shankland, Robert. (1970). Steve Mather of the National Parks: A Biography. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Yard, Robert Sterling. (1917). The National Parks Portfolio, Second Edition. U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington D.C. NPS History Collection, Harpers Ferry, WV.

Yard, Robert Sterling. (1931). The National Parks Portfolio, Sixth Edition. U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington D.C. Accessed August 24, 2023, at https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/portfolio/index.htm.

Tags

- bryce canyon national park

- cedar breaks national monument

- glacier national park

- grand canyon national park

- zion national park

- nps history collection

- nps history

- stephen t. mather

- stephen tyng mather

- railroad history

- advertising

- tourism

- travel

- see america first

- hfc

- fred harvey company

- great northern railway

- atchison

- topeka and santa fe railway

- national parks porfolio

- nps establishment