Last updated: June 1, 2023

Article

50 Nifty Finds #25: Ranger Spies?

Mather, Stephen Mather. Not the correct M? How about Albright, Horace Albright? Doesn't ring a bell with Q? Ok, we admit they don’t have the same flair as the name of a certain British spy, but there’s still a story to tell here. Spies in the National Park Service (NPS)? As far as we know there weren’t any real ranger spies operating in national parks, but the NPS did use secret codes to communicate. That's spy-like, right? Fortunately, enough time has passed that we can tell you about it without having to … you know.

Hidden in Plain Sight

It’s easy to understand why spies, diplomats, and the military would use complex encryption systems to keep messages secret, but why would the NPS need to do that? While we don’t usually have “top secret” information, we sometimes have confidential, legally privileged, or protected personally identifiable information. Sensitive information can be password protected or encrypted in e-mail messages sent outside NPS computer networks today, but what about 100 years ago?

Letters were the most common form of communication. Some sensitive information was sent by mail, but delivery could take a long time. In the 1910s and 1920s, most national parks didn’t have telephone lines. Where telephones were available, they relied on operators who could eavesdrop and most calls were made on shared party lines. Fax machines, long valued for their ability to send confidential information, existed but weren't commercially viable yet.

When you had something to say and you wanted to say it quickly, telegrams were the way to go—but they weren't secure either. The sending and receiving telegraph operators, delivery messengers, and others could read the messages (and share what they read). Imagine how many people can read a postcard along its delivery route, and you'll get the idea. The desire for a degree of privacy even when sensitive information wasn't involved, coupled with the cost to send a telegram (they were priced by the word), led some companies to published code word directories. Soon, nonsense words were created to help convey a lot of information is as few “words” as possible. For example, a “Dear John” telegram might simply send the word “COQUARUM” to mean “engagement broken off”—and you thought being dumped by text message was new!

Get Cracking!

The encryption system used by the NPS appears to be pretty straightforward—a codebook was used to substitute gibberish or real words for the intended words. Encipherment, such as a one-for-one letter substitution system, isn’t involved because the words are different lengths. Using codebooks is reasonably secure as long as access to them is highly restricted. Double encryption, in which words in a codebook are then enciphered, is even better because if the cipher is broken but the code system is not, the message is still unreadable, and vice versa. We don't believe that the NPS used double encryption. However, we haven’t been able to find a copy of any NPS codebooks in NPS or National Archives collections. Because of their nature, they would have been closely held and the copies destroyed annually as new ones were issued.

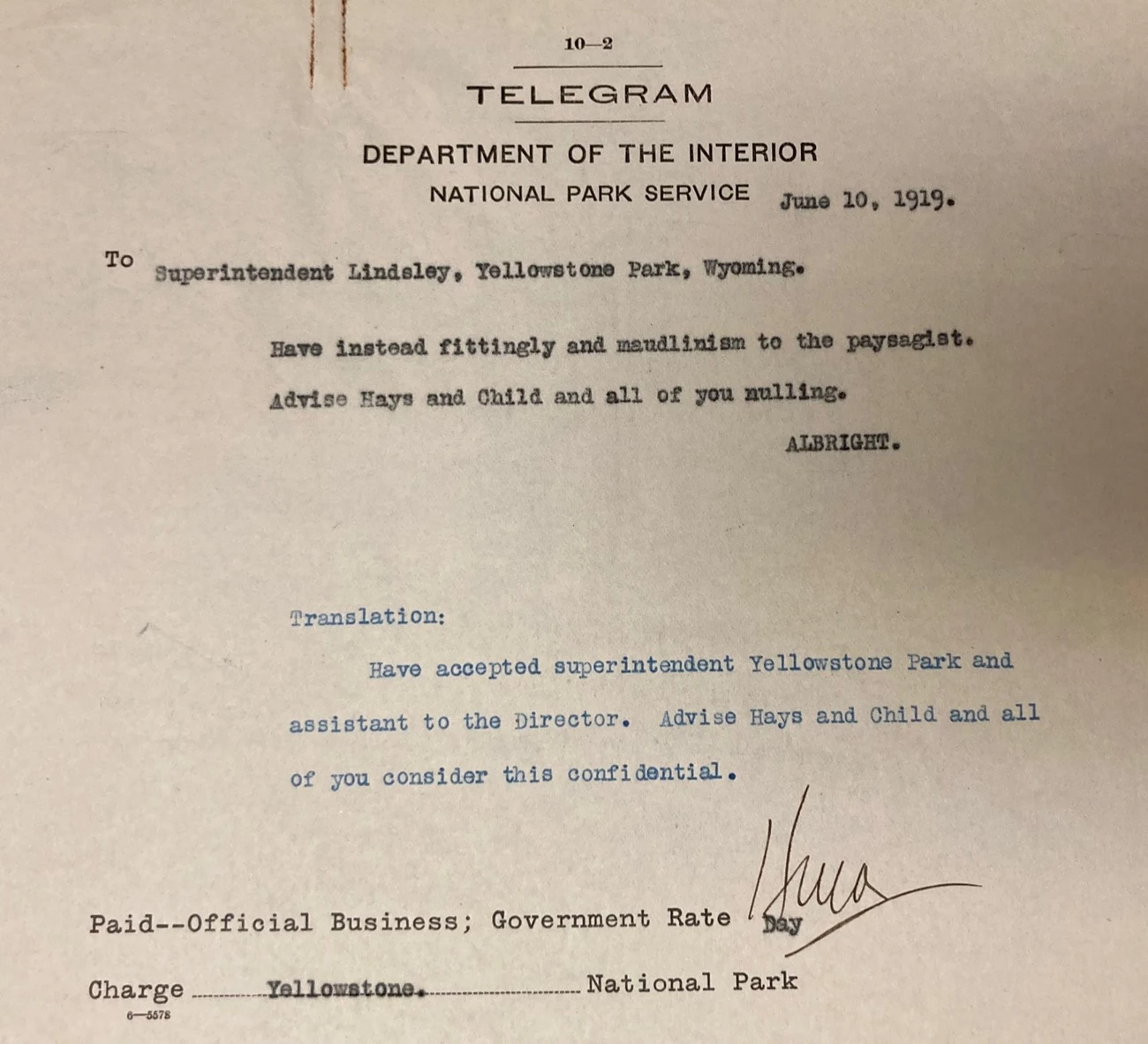

The NPS History Collection includes a couple of encrypted telegrams that include the original message sent and, helpfully, their translations. One example was sent by Assistant Director Horace M. Albright to Yellowstone Superintendent Chester A. Lindsley on June 10, 1919. It reads:

Have instead fittingly and maudlinism to the paysagist. Advise Hays and Child and all of you nulling.

We've provided a selection of known code words and their meanings below. All of them are genuine NPS code words used in 1919, but only some of them are used in this telegram. Can you crack Albright's message?

Vagrant = soldiers

Toadflax = park

Maudlinism = assistant

Upheaving = sending

Vettura = telegrams

Fittingly = Yellowstone superintendent

Unwished infesting = senators

Ilbamb = urging

Instead = accepted

Unstopped = return

Nulling = consider this confidential

Infesting ubadudaeum = agitation

Paysagist = director

Vetage = take

When you think you've figured it out, scroll down to find the answer below.

When translated, the encrypted message reads:

Have accepted superintendent Yellowstone Park and assistant to the director. Advise Hays and Child and all of you consider this confidential.

You've heard stories of people being fired by text message, but how about by telegram? Technically, Lindsley wasn't fired (he continued to work for the NPS until 1935), but Albright's encrypted message tells Lindsley that he is taking his job. As the telegram form indicates, he even charged Yellowstone for the price of doing so! It was sent the day after Albright accepted the position. It would have come as a complete surprise to Lindsley, who had been doing the job for 2½ years. He continued acting as superintendent until Albright arrived a month later.

Lindsley was a civilian employee at the US Army-controlled Yellowstone National Park when the NPS was created on August 25, 1916. He had worked under army superintendents at the park since 1894. Albright seemingly downplayed Lindsley's contributions when he later recalled, "When the army departed, he had taken over in a caretaker capacity as acting superintendent, and had been holding things together during the unsettled period when the army had been sent back in and then out again." In fact, when Stephen T. Mather appointed Lindsley acting superintendent on October 15, 1916, he was the obvious choice for the job. His knowledge, experience, and insight gained over the previous 22 years during the army's administration brought stability during a difficult period. When Albright submitted his resignation from the NPS in March 1919, he recalled that he had wanted the Yellowstone superintendency in 1916. To keep Albright in the NPS, Director Mather offered him the top job at Yellowstone, provided he also served as assistant director for field operations. Lindsley became assistant superintendent.

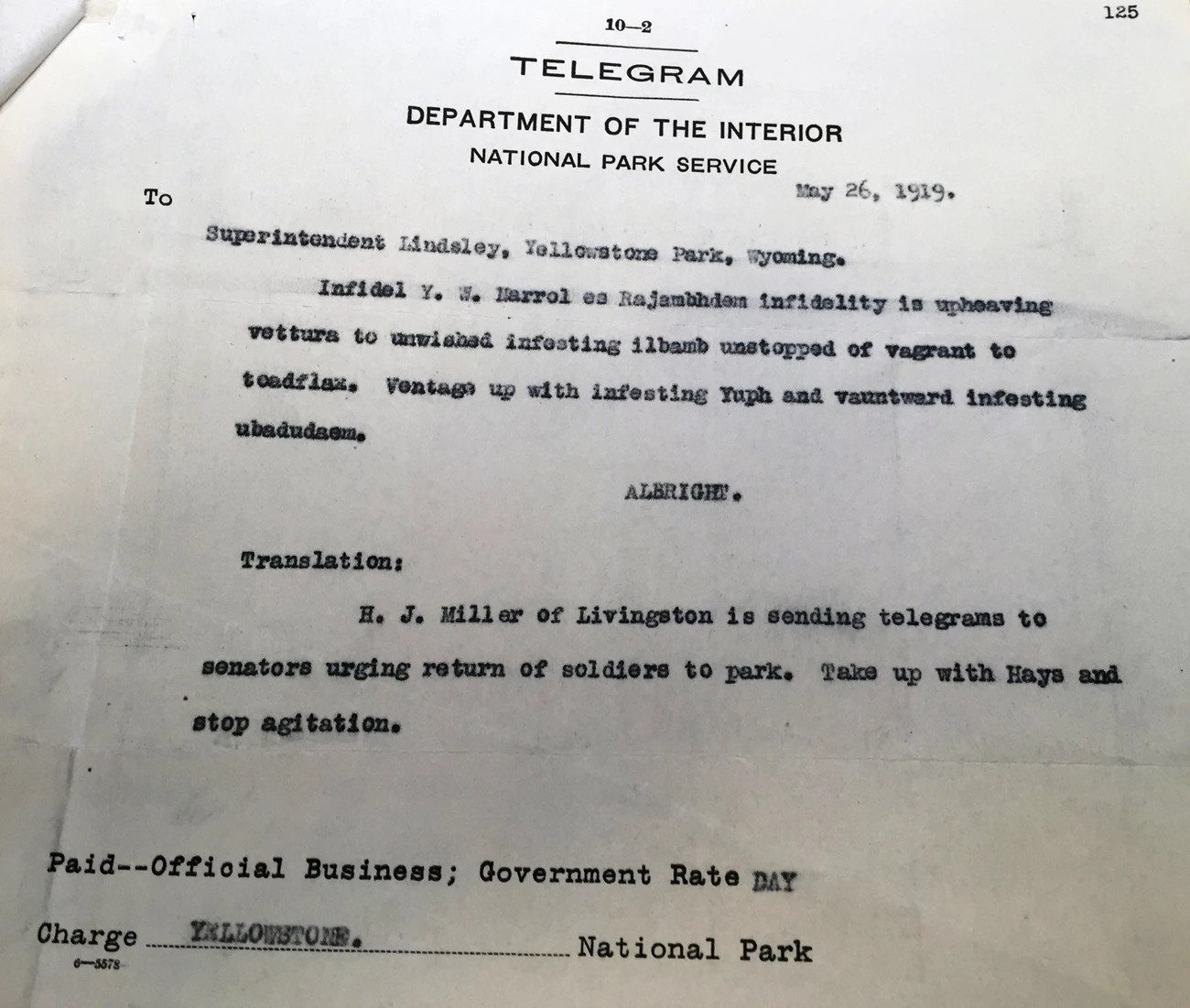

Lindsley's reception of the news aside, why did Albright encrypt this interesting but seemingly mundane message? Certainly, he wouldn't have wanted the media to "scoop" an official announcement by the Department of the Interior. More importantly, however, NPS control of Yellowstone was still uncertain. Just two weeks earlier another encrypted telegram from Albright to Lindsley warned of renewed efforts to bring the US Army back into the park. Politics, it seems, was another reason the NPS had secrets it didn't want to share.

Sources:

--. (2021, August 9). “The History of Fax (from 1843 to Present Day).” Accessed May 14, 2023, at https://faxauthority.com/fax-history/

Albright, Horace M. as told to Robert Cahn. (1985). The Birth of the National Park Service: The Founding Years, 1913-33. Howe Brothers: Salt Lake City, Utah.

Assembled Historic Records of the NPS (HFCA 1645), NPS History Collection, Harpers Ferry, WV.

National Park Service. (1991, May 1). Historic Listing of National Park Service Officials. Accessed May 14, 2023, at https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/tolson/histlist.htm

Pers. comm. (2022, August 24). David Robarge, CIA chief historian, to Nancy Russell, NPS History Collection archivist.

Shaw, Amanda. (2016, July 1). “The Superintendents: Chester A. Lindsley.” Accessed May 14, 2023, at https://www.nps.gov/yell/blogs/the-superintendents-chester-a-lindsley.htm

Spencer, Luke. (2015, June 2). “Technology You Didn’t Know Still Existed: The Telegram.” Accessed May 14, 2023, at https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/telegrams