Last updated: November 29, 2025

Article

50 Nifty Finds #16: Uniformity and Diversity

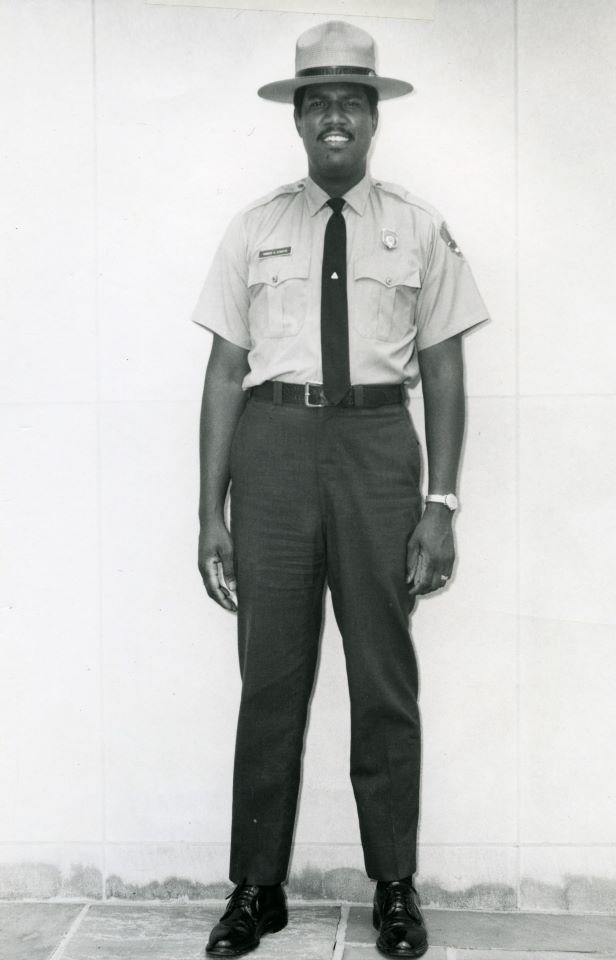

The National Park Service (NPS) uniforms in the NPS History Collection reflect the development and evolution of the iconic park ranger image, but they also do much more. Although many look similar, each uniform weaves together the unique story of the person who wore it and their contributions to the NPS mission. Sometimes the uniforms and their stories also reflect larger issues of the NPS and American society. That’s the case for the uniforms worn by Robert G. Stanton. His was a career of firsts made possible by the civil rights era, the kindness of strangers, visionary mentors, and Stanton’s own determination, hard work, and dedication. Wearing his “green and gray” uniform, Stanton rose through the ranks from one of the first Black rangers in the early 1960s to the first African American director of the NPS. Along the way he and others shone a light on a lack of diversity in the NPS workforce and the need to make national parks relevant and welcoming to people of color.

Robert G. Stanton was born in Fort Worth, Texas, in 1940. He grew up in Mosier Valley, a close-knit, African American community established by freed slaves after the Civil War. His father was a hay contractor; his mother was a short-order cook. He was the youngest of four children. He attended elementary school in Mosier Valley, where the furniture, books, and other equipment were hand-me-downs from the white school. In 1950 Stanton’s parents were part of a successful federal lawsuit to improve school conditions for their children, resulting in construction of a new segregated grade school for the community. For high school, however, Stanton was bused 30 miles to the segregated I.M. Terrell High School in Fort Worth. He graduated from there in 1959. He went on to earn a BS in physical science from Huston-Tillotson College (now a university) in 1963.

Stanton was recruited for a job with the NPS through a program started by Secretary of Interior Stewart Udall. As Stanton recalled, Udall “only saw Black faces in the mailrooms or doing janitorial or maintenance work or maybe in clerical jobs.” Dissatisfied with the lack of diversity in the Department of Interior’s workforce, Udall sent Interior recruiters to historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) for the first time. During his junior year at Huston-Tillotson, Stanton was recommended to the recruiter by the college president.

Stanton accepted a seasonal park ranger position at Grand Teton National Park for the 1962 summer season. Four other students from Huston-Tillotson got ranger jobs that year. M.B. Micheaux joined Stanton at Grand Teton, W. Preston Shaw went to Yellowstone National Park, and Curtis Robinson and William James went to Rocky Mountain National Park. From this group only Stanton continued to work for the NPS after 1962. The three Black rangers at Grand Teton in 1962 were Stanton, Micheaux, and William Kinard, from Livingstone College in North Carolina.

About 40 HBCU students were offered positions at various parks, but not everyone showed up for duty at their parks. As Stanton noted in a 2006 oral history interview, it wasn’t realistic for many to pay their own way to parks, buy their uniforms before they arrived, and support themselves until they received their first paychecks—no matter how much they may have wanted to be park rangers. Stanton was only able to take the job because a prominent white farmer who once employed him and his father agreed to cosign a $250 bank loan. The racism African Americans experienced traveling in the United States prior to the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Udall’s plan to place rangers in parks that had never had Black employees were probably also considerations that kept some from taking the offered positions.

Secretary Udall personally signed the students’ letters confirming their selection for ranger positions. Stanton still treasures his. The trip to Grand Teton National Park was his first train ride and the first time he traveled outside Texas. It was also his first visit to a national park. Arriving in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, Stanton "walked around and didn't see any Black faces." Hoping to find a family to stay with before his official start with the park, he was told, "No Black folks live up here." Fortunately, a man who owned a motel put him up for the night, allowing him to pay after he got his first paycheck, as he had no money for a hotel.

Grand Teton was also Stanton’s first integrated workplace experience. When a local bar in Jackson Hole wouldn’t serve them one night, Superintendent Harthon L. Bill, chief ranger Russell Dickenson, and assistant chief ranger Jack Davis spoke to the business and civic leaders in town. The incident wasn’t repeated. On his days off Stanton worked at a local ranch helping put up hay.

He later recalled, “The Teton experience in 1962 influenced me to seriously consider at some point in time pursuing a career with the National Park Service. What was really defined for me was the quality of the professional staff.” Not all of the African Americans hired by Udall were as warmly accepted by white employees at other national parks as Stanton, Micheaux, and Kinard were at Grand Teton. Stanton stated, “I can say without any hesitation that the three African Americans working at Grand Teton in ’62 were warmly and truly welcomed to the workforce.”

After graduation, Stanton returned to Grand Teton for a second season as a temporary ranger. His NPS career was delayed, however, when he joined the Huston-Tillotson staff as director of public relations and alumni affairs. The position came with a grant for graduate work at Boston University. In 1966 he returned to the NPS with a permanent GS-9 position in personnel management in the Washington Office. This position made him was one of a handful of African Americans working in professional jobs in the NPS. He later recalled, “I think I was the highest-ranking African American in the entire headquarters of the National Park Service.”

In 1969 Stanton moved to National Capital Parks-Central (now National Mall and Memorial Parks) as the management assistant. The next year NPS Director George B. Hartzog Jr. promoted him to superintendent of National Capital Parks-East, making him the first NPS African American superintendent. (Captain Charles Young served as acting superintendent of Sequoia and General Grant national parks in 1903 under a US Army appointment.) He was also selected by Hartzog to attend the Federal Executive Institute. In 1971 Stanton became superintendent of Virgin Islands National Park. Director Hartzog assigned him to the position to develop better relationships with the governor and legislature and to address land-acquisition needs. He also worked out a memorandum of agreement for NPS management of Christiansted National Historic Site.

In 1974 he became deputy regional director for the Southeast Region in Atlanta, Georgia. He returned to the Washington Office in 1976 as assistant director of park operations. He was appointed deputy director of the National Capital Region in 1978. He held that position for eight years before returning to the Washington Office as associate director for operations, his first Senior Executive Service (SES) position. Stanton returned to the National Capital Region as regional director in 1988, a position he held until his retirement on January 3, 1997.

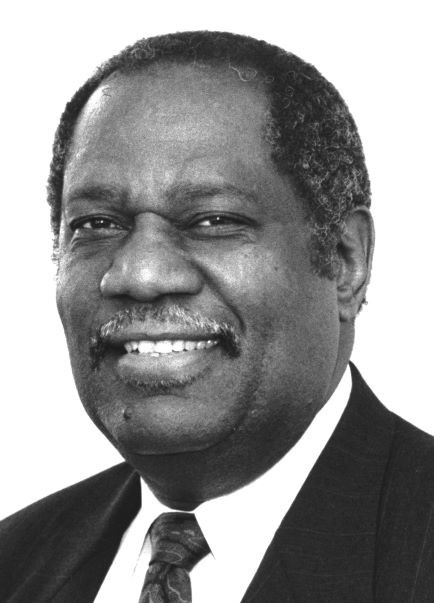

His retirement was short lived, however, because President Bill Clinton nominated him for NPS director. In 1996 the NPS director position became subject to Senate confirmation rather than a unilateral presidential appointment. Stanton was the first NPS director to go through that process. He was unanimously confirmed by the Senate on July 31, 1997. He began his tenure as the 15th director of the NPS—and the first African American director—on August 4, 1997.

The civil rights era and laws that required special actions in recruitment, hiring, and other areas designed to eliminate the effects of past discrimination had resulted in an increasing trend for diversity in the 1960s and 1970s. Much of that progress stalled in the 1980s and 1990s, however, with a backlash against affirmative action. Although the NPS continues to suffer from a workforce diversity deficit, as director Stanton promoted diversity in the NPS workforce and opportunities for young people. Under his leadership, the NPS also commissioned its first public survey to understand the barriers that keep people of color from visiting national parks and to create solutions that addressed the resulting environmental justice issues around national parks.

He also supported diversity within the National Park System. During his tenure, 10 parks were established, four were redesignated, more than 20 areas were authorized for study, and Congress adjusted the boundaries for about 30 more. Director Stanton is particularly proud that Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site, Minidoka Internment National Monument (now Minidoka National Historic Site), Little Rock Central High School National Historic Site, Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site, and Rosie the Riveter World War II Home Front National Historical Park were authorized during his directorship. He recalled, “I knew growing up as a youngster that the popular media, in particular the newspapers and magazines, were devoid of the full story of America. The textbooks might make references to it, but [didn’t] really fully disclose our entire history.” He described himself as “an advocate for preserving and providing for more public understanding and appreciation of the richness of our diverse cultural heritage, but also, I was interested in telling the full story by bringing in new areas within in the park system.”

The Underground Railroad Network to Freedom Act of 1998, which created the Network to Freedom Program, was also enacted during his tenure. The program “honors, preserves and promotes the history of resistance to enslavement through escape and flight” and “consists of sites, programs, and facilities with a verifiable connection to the Underground Railroad.” There are now over 700 Network to Freedom locations in 39 states, Washington DC, and the US Virgin Islands.

The NPS Natural Resources Challenge was implemented in 1999. The strategy included greater use of science in NPS decision making, expanding air- and water-quality monitoring programs, conducting baseline natural resources inventories, protecting native species and their habitats, providing leadership for a healthy environment, connecting parks to people, and providing a career ladder for staff working in natural resource management positions. The Save American's Treasures program, “Experience Your America” campaign, and the national parks pass also began during his tenure.

Director Stanton recognized the need to shift from a traditional superintendents’ conference to a different, more inclusive kind of meeting. He had three goals for the Discovery 2000 conference: to develop a vision of the NPS's role in the life of the nation in the 21st century; to inspire and invigorate the Service, its partners, and the public about this vision; and to develop new leadership to meet the challenges of the future. The meeting was a gathering of over 1,200 participants including a broad mix of NPS Washington, regional office, and park staff and representatives from various federal, tribal, state, and local agencies; concessionaires; non-profit organizations; and international parks. Less than 25 percent of the participants were park superintendents, and only 70 percent of participants were from the NPS.

Director Stanton received five honorary doctorate degrees and numerous awards throughout his career, including the Department of the Interior’s Distinguished Service Award. His term as NPS director ended in January 2001, but that hasn’t stopped his advocacy for national parks and issues of diversity and inclusion. In 2001 he was invited to teach at the School of Forestry and Environmental Studies at Yale University. His course “National Parks: Lessons in Diversity, Environmental Quality, and Justice,” covered NPS history and the preservation of biological and cultural diversity. In 2002, Director Stanton was appointed ambassador by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature and attended its World Park Congress.

In 2009 he returned to Federal service, serving in the Office of the Interior Secretary for five years. In 2014 he was appointed by President Obama as a member of the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation. He was a member until 2020. He has also served as a visiting professor at Howard and Texas A&M universities.

He went on to consult and serve on many boards of directors. He has been actively involved in organizations like the Student Conservation Association, Inc., Grand Teton National Park Foundation, and African American Experience Fund of the National Park Foundation. Now in his 80s, he continues to travel and speak on issues of national parks, historic preservation, diversity, and inclusion. He currently serves as Scholar-in-Residence at the University of Missouri-St. Louis. In November 2022 he was part of a strategic planning meeting supporting the NPS History Collection’s ongoing efforts to build a more relevant and inclusive museum collection.

The NPS History Collection includes Director Stanton’s winter and summer uniforms and accessories, oral history interviews, some of his papers, and photographs of him during his career. These materials represent the personal experiences and accomplishments of Stanton throughout all stages of his career. They also reflect complex relationships between the NPS and communities of color, the opportunities that the Civil Rights Act of 1964 brought for some in the NPS workplace and American society, and the importance of developing and maintaining a relevant National Park System for all Americans.

Although Stanton remains the only African American appointed NPS director, since he left office in 2001 the NPS has had its first women directors (Fran P. Mainella and Mary Bomar), first Latino acting director (David Vela), and the first Native American director (Chuck Sams). Despite those gains, at the field level—and for the public—more work remains to be done to increase diversity and inclusion.

Director Stanton’s collection also reminds us of the importance of visionary leaders like Stewart Lee Udall, George B. Hartzog Jr., Russell E. Dickenson, and others—including Stanton himself—in committing to diversity and inclusion in the NPS. As he noted in a 2016 interview, “It takes courageous leadership at top levels—superintendent, regional director, director, and certainly Secretary [of Interior]—to monitor what is taking place and make some strategic actions to get the kind of workforce representation that we’re striving for.” It also takes the commitment of individual hiring managers at all levels of the organization to build a more inclusive workforce. Robert Stanton’s story demonstrates not only the difference that an individual can make in implementing the NPS mission, but also the importance of peers, division chiefs, mentors, and others in "green and gray" to create places that welcome everyone.

Sources:

--. (1962, May 13). “4 Students of H-T Get Park Jobs.” The Austin American (Austin, Texas), p. 6.

McDonnell, Janet A. (2001, January). “ The National Park Service Looks Toward the 21st Century: The 1988 General Superintendents Conference and Discovery 2000.” Accessed on February 26, 2023, at https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/hisnps/NPSThinking/suptreport.htm

McDonnell, Janet A. (2006). Oral History Interview with Robert G. Stanton, Director National Park Service 1997-2001. National Park Service. NPS History Collection, Harpers Ferry, West Virginia (HFCA 1817).

National Park Service, “15th National Park Service Director Robert Stanton.” Accessed February 17, 2023, at https://www.nps.gov/articles/director-robert-stanton.htm

National Park Service, “National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom.” Accessed February 22, 2023, at https://www.nps.gov/orgs/1205/index.htm

National Park Service (1999, August 12). “Protecting America's Natural Heritage: National Park Service Announces New Plan to Strengthen and Revitalize Natural Resource Programs in National Parks.” Accessed February 25, 2023, at https://www.nps.gov/nature/pressrelease.htm#:~:text=The%20Natural%20Resource%20Challenge%3A%20The%20National%20Park%20Service%27s,heritage%20within%20the%20complexities%20of%20today%27s%20modern%20landscapes.

Pers. comm. (2023, March 2). Robert G. Stanton to Nancy Russell, archivist of the NPS History Collection.

Yogev, Yanit. (2017, June). Diversity, Equity and Inclusion in the National Park Service: Narratives, Counter-narratives and the Importance of Moving Beyond Demographics. MA Thesis, Evergreen State College. Accessed February 26, 2023, at https://collections.evergreen.edu/files/original/b83ea28c3ef839f79d69019a067bfc6cb75ff653.pdf