Last updated: January 30, 2023

Article

50 Nifty Finds #12: Glamping Gear

The word “glamping” was officially added to the Oxford English Dictionary in 2016. For many, glamping combines the love of outdoors with the creature comforts of home, including good food and a comfortable bed. That combination aptly describes a 1915 backcountry trip that was instrumental in gaining support for the creation of the National Park Service (NPS). As camping equipment improved in the 1920s, friends gave NPS Director Stephen T. Mather some of the latest, high-quality glamping gear available.

A Man Named Mather

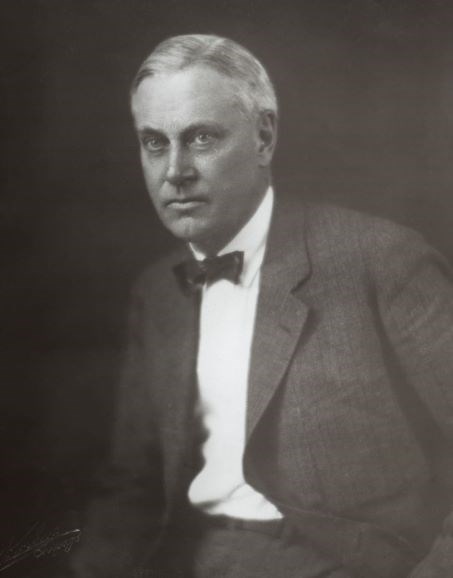

Before becoming the first director of the NPS in 1917, Stephen T. Mather (1867–1930) was a very successful businessman. His education and wealth allowed him to meet some of the most influential people of the time, support charitable causes, lend support to people he felt had promise, and travel in the United States and Europe. He joined the Sierra Club in 1904 and the next year accompanied them on a climb up Mount Rainier. Mather became an ardent mountaineer and conservationist. In 1912 he led his wife, daughter, and nine friends on a backcountry trip in the Kern River Canyon area and Sequoia National Park where they ran into John Muir along the way

Mather was sworn in as an assistant to Secretary of the Interior Franklin K. Lane on January 21, 1915. At the time, there were 13 national parks and 18 national monuments but no government bureau to manage them consistently and protect them from external pressures. As Mather’s biographer Robert Shankland noted, Mather and his 25-year-old assistant Horace M. Albright needed to:

- Get Congress interested enough in national parks to make vast increases in their appropriations and to authorize a bureau of national parks

- Organize and create a functioning government bureau

- Get the public excited about national parks

- Make travel to parks easier

- Sell national park integrity to encourage Congress to add to the system, protect the parks created, remove private holdings within parks, and prevent inappropriate sites from being added to the system

No pressure, then.

Building Support Through Glamping

Mather travelled at least 30,000 miles in his first 11 months promoting parks and the idea of a bureau of national parks. One significant event during that period became known as the Mather mountain party. From July 14 to 27, 1915, Mather led a group of 18 Department of the Interior employees, newspaper and magazine writers and editors, authors, photographers, conservationists, politicians, businessmen, and scientists on a backcountry trip in California’s Sierra Nevada mountain range. Mather paid for everyone’s transportation, food, bedding, and other expenses for the trip.

The Mather mountain party was glamping at its most sumptuous. Albright later wrote, “Mather spared no expense for the outing.” Sequoia National Park ranger Frank Ewing and a crew of wranglers took care of the men’s horses and the mules used to carry the equipment, food, and belongings. They built the campfires and handled most of the chores associated with backcountry camping. Chinese cook Ty Sing and his assistant Eugene provided lavish meals that included cantaloupe, grapefruit, apples, cereal, eggs, sausage, pancakes with maple syrup, freshly baked sourdough bread and rolls, coffee, fresh lemonade, sardines, steak, potatoes and gravy, honey, soup, salad, fried chicken, venison, trout, apple pie, cheese, and crackers. On one memorable evening they made a traditional English plum pudding with brandy sauce. Albright noted, “‘Roughing it’ was not a term to be used for our dining. Every night on our trip, the table was set with a snowy white linen tablecloth and napkins, silverware, and China. Ty Sing and Eugene somehow managed to wash and iron the linen each day in addition to packing, traveling, unpacking, baking, and cooking meals.” The bedding was described by Albright as “newfangled air mattresses and sleeping bags.” Bicycle tire pumps were available to inflate the mattresses for those who needed them.

The trip was a promotional success, and the participants became advocates for national parks. They supported purchasing the Giant Forest, expanding Sequoia National Park, and expanding General Grant National Park to include the Kings Canyon area. Most of the party agreed with the need to create a national park service. The writers, editors, and politicians among them provided support and publicity leading up to (and long after) the creation of the NPS a year later on August 25, 1916.

Albright reported that Mather provided each man with a new sleeping bag and air mattress but none of the camping gear is known to survive. Some of it may have been taken home by members of the party, but it’s more likely that it returned to Sequoia National Park with the horses and other gear where it was put to use. However, the NPS History Collection does include some of Mather’s later glamping gear.

The Gift of Glamping

Although Mather owned and used other camping gear, the equipment in the NPS History Collection is part of a “camping outfit” given to Mather around 1926. The gift came from four of his close friends—Albright, Oliver Mitchell, Francis Farquhar, and Charlie Carnahan.

In a November 30, 1931, memo, Albright described the gift. “The bag itself is a Woods eiderdown sleeping bag, one of the best made. Besides this, there are some blankets, a pair of shoes, a water bucket, and there should be some saddlebags. It is a fine outfit, worth approximately $200.”

The men were very good friends indeed, as today the equivalent outlay is approximately $3,350. Even split four ways, it was a very generous gift. The sleeping bag was certainly special. Made by Woods Manufacturing Company Limited in Odgensburg, New York, it was officially called a Woods Arctic eiderdown sleeping robe. Newspaper advertisements from 1926 describe it as “proof against ice, snow, or cold. Relaxed in every muscle, toasty-warm to the tips of your toes, you may sleep through the winter’s fiercest blizzard on an open porch. An ideal protective robe for campers, hunters, tourists, etc. Arctic Eiderdown Robes have been used in the highest altitudes and frost has never penetrated their inner recesses.” The list price was $40 and up (about $625 dollars in 2022). The advertising claims appear warranted. Two years after Mather received his gift, Richard E. Byrd used the same sleeping bags on his Antarctic expedition.

The canvas and rubber air mattress was made by the Atlantic-Pacific Manufacturing Corporation of Brooklyn, New York. The company was best known for making marine life-saving equipment such as life vests and ring buoys. The mattresses became popular for camping and expeditions and appear to be an improved model over air mattresses available in 1915. A 1923 advertisement of new goods in The India Rubber World described Atlantic-Pacific’s mattress as follows:

“The inside air section of the pneumatic mattress is made of four layers of pure rubber, calendered to a high-grade cotton fabric, the rubber surface being exposed so that repairs are easily made. The mattresses are cut from rubberized cloth and are vulcanized after being made up, so that all parts are welded together, and joint leaks are impossible. They are tufted with a patent stay which holds the walls always in the same relative position to one another vertically, thus insuring a perfectly even surface regardless of the location of the weight. Camp mattresses are furnished with covers of khaki or brown duck.”

Instructions printed on the mattress cover label note, “ALWAYS keep a blanket on top of mattress to keep warm in cold weather and to prevent sweating in hot weather.”

The rest of the camping gear was more common. The wool camping blankets were sold by many retailers, including the Sears and Roebuck Company. The pillow with tan and white ticking was also commonly available. In 1926 collapsible water buckets could be bought for about a dollar each.

Lost and Found

On November 5, 1928, Mather suffered a stroke. He submitted his resignation as director on January 8, 1929. He recommended Albright to succeed him, which he did on January 12. After a year of physical therapy and significant progress towards restoring his mobility, Mather died unexpectedly on January 22, 1930, age 62.

Following Mather’s death, Yosemite National Park Superintendent Charles Goff Thomson wrote to his widow, Jane Mather, asking if he could have the Woods sleeping bag. His letter isn’t available, but Mrs. Mather’s response gives some insight into it. On July 12, 1930, she wrote, “I am very glad that you screwed up your courage to write to me regarding Mr. Mather’s sleeping bag, for I am very glad to have you take it for your own and use it, and I know he would be also.” Six days later Thomson replied, “I certainly appreciate your letter of July 12 and will always keep the sleeping bag.” This exchange suggests that Thomson had the sleeping bag, and by extension the rest of the camping gear, at Yosemite in 1930.

Thomson must have been very disappointed when the next summer Director Albright wrote to him, “According to my recollection, you have at Yosemite Mr. Mather’s sleeping bag and camping equipment, all of which he gave to me. I will need this outfit during the summer. I would be very grateful to you if you would have this equipment carefully taken from the dunnage bag, aired, repaired, and then shipped to Yellowstone Park; or perhaps you can just hold it at Yosemite until I come."

Thomson doesn’t seem to have mentioned to Albright that Mrs. Mather had given him the sleeping bag. Instead, he replied, “According to our records in this office, we mailed to you at Yellowstone National Park in July 1929, Mr. Mather’s sleeping bag. This bag was shipped from Yosemite on July 10 on Government Bill of Lading I-17686. Your letter of July 18 [confirms this]. However, if you desire another sleeping bag, we can without doubt arrange to ship you one at Yellowstone as requested.” Unfortunately for Thomson, Albright was undeterred and directed him to contact Sequoia, Yellowstone, and Lassen Volcanic national parks to check if it was there, noting, “Had it last in Lassen in September ‘29 and recollection is I sent it to Yosemite for winter keeping.”

Thomson wrote to the parks as directed, noting, “The sleeping bag has evidently been stored at one of the parks which Director Albright visited during the trip and as it was a personal gift of Mr. Mather, he is very anxious to locate it.” To Albright on June 30, 1931, he wrote, “In accordance with your wire we have today written the superintendents regarding sleeping bag which was shipped to you at Yellowstone in 1929. While this bag was not returned to Yosemite, we will, of course, be glad to arrange to let you have another one.” It’s possible that Thomson genuinely didn’t know the whereabouts of the camping gear, but his earlier correspondence with Jane Mather suggests otherwise. Albright would not accept an alternative sleeping bag replying on July 3, “I hope you can trace this property as it is very important to me and quite valuable. It must be there in Sequoia, Yosemite, or Lassen parks.”

Superintendent Lynne W. Collins at Lassen Volcanic National Park confirmed that he sent Mather’s sleeping bag back to Yosemite in June 1929 as Director Albright requested. Sequoia National Park Superintendent John R. White also denied having the camping gear. On July 6, 1931, Joseph Joffee, assistant to the Yellowstone superintendent, replied “we have located this in our commissary at Mammoth and are awaiting instructions for shipment.” Thomson informed Albright that the equipment was found at Yellowstone—but not until November 24, 1931. The reason for the delay is unknown.

On November 30, 1931, Albright wrote to Thomson,

“Your letter of November 24, in regard to the sleeping bag, reached me this morning. I don’t think that you have found my sleeping bag. There can be no mistaking the outfit. It is in a big war bag, leather bound, and has a heavy leather handle in the middle of the side of the bag as well as on the top. The top and bottom are of leather and the whole thing is leather bound. Mr. Mather’s name is painted on the bag. I do not want the bag in the East. I want it kept either in Yellowstone or Yosemite, or somewhere else where there is a good warehouse. It looks as though this bag reached Yosemite and was there misplaced, or perhaps was even stolen at the station or on the way up. However, it looks from the bill of lading as if it had been received at Yosemite and I am hoping against hope that it will be found around the warehouse. Mr. Mather particularly wanted me to have this bag. In view of the value of the outfit and the expense that would be involved in replacing it, I would naturally like to have it back. I would be grateful if you would have the search continued.”

Seemingly admitting defeat, Thomson notified Albright on December 15, 1931, that “We have finally located that sleeping bag outfit.” It’s noteworthy that he doesn’t say where he found it. He describes it as follows:

“It is a Woods-Arctic sleeping bag, large size, with a pneumatic mattress. In it there are two woolen blankets, one pillow, one collapsible water bucket, the whole thing packed in a heavy canvas bag—the ends of which are made of heavy leather. The name ‘Stephen T. Mather’ is faintly marked on the canvas bag. No boots are in the bag, but there is a pair of large black, engineer type, with composition soles, in the fire shed which we assume to be yours and which we are attaching with a cord to the outside of the bag.”

In fact, there were several other items in the bag. After finding the bag, Thompson added a tag with a list of the contents. A comforter and mosquito netting not previously mentioned in the correspondence was noted on the tag. The saddle bags Albright mentioned were not found with the rest of the gear.

Thomson had the bag of gear “put away in the warehouse, marked with two shipment tags which state: ‘Not to be used under any circumstances. This bag is property of Director Horace M. Albright.’” He went on to state, “I am happy to have finally set your mind at rest concerning this outfit. Personally, I had rather not accept the responsibility for it, but as it is more convenient for you [I] will take good care of it, and on my periodical inspections of the warehouse I will make it routine always to go upstairs to see that it is there.”

It's not known if Albright used the camping gear before he resigned from the NPS on August 9, 1933. Given his intense interest in finding it a couple of years earlier, one would expect that he would have taken Mather’s bag of camping gear with him, but he didn’t.

From Warehouse to Museum

The history of Mather’s camping gear for the next 40 years is murky. It presumably stayed in the Yosemite warehouse for many years. It resurfaced at Yellowstone National Park by1966, but it’s unclear why or when it was sent to that park. A photograph taken by a Yellowstone employee that year documents that by then only the air mattress, pillow, one blanket, and collapsible water bucket remained in the dunnage bag with Mather’s name on it. The sleeping bag, one blanket, comforter, mosquito netting, and hi-cut boots listed on Thompson’s tag were missing.

It’s possible that Albright took the Woods Arctic sleeping bag with him upon retirement. If so, it’s unclear why he left the other gear behind given the value of the entire camping outfit. Superintendent Thomson remained at Yosemite for four years after Albright left the NPS. Not unreasonably, he may have felt justified in taking the sleeping bag if Albright hadn’t, given that Mrs. Mather had told him he could have it. However, that can’t be proven either and it doesn’t explain the rest of the missing equipment.

Because Mather’s camping gear wasn’t museum property and was stored in a warehouse at Yosemite for decades, anyone could have taken it, or it may have inadvertently ended up in a park equipment cache where it was used until it was no longer serviceable and then discarded. Unfortunately, no records have been found, and the fate of the missing gear remains a mystery.

Yellowstone returned Mather’s gear to Yosemite around 1968, and it was accessioned to the Yosemite museum collection. Amazingly, Thomson's original tag was still on the bag. Six years later Yosemite transferred the air mattress, blanket, and the pillow to the NPS History Collection. The duffle bag and collapsible water bucket remain in the Yosemite collection.

Sources:

-- (1923, February 1). “Air Mattress which Holds Its Shape.” The India Rubber World, Vol. 67, pg. 309.--“From Camping to Glamping: History and Evolution.” Accessed January 12, 2023, at https://glampinghub.com/blog/history-of-glamping/

Albright, Horace M. and Cahn, Robert. (1985). The Birth of the National Park Service: The Founding Years, 1913-1933. Howe Brothers: Chicago.

Albright, Horace M. and Schenck, Marian Albright. (1997). Creating the National Park Service: The Missing Years. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman.

Assembled Historic Records of the NPS (Series I). NPS History Collection (HFCA 1645), Harpers Ferry, West Virginia.

HFCA-00329 accession folder. NPS History Collection, Harpers Ferry, West Virginia.

National Park Service. (1991). Historic Listing of National Park Service Officials. National Park Service. Washington, DC.

Pers. Comm. (2022, December 12). Laura Bender, registrar at Yosemite National Park, to Nancy Russell, NPS History Collection archivist.

Pers. Comm. (2022, December 5). Miriam Watson, curator at Yellowstone National Park, to Nancy Russell, NPS History Collection archivist.

Shankland, Robert. (1970). Steve Mather of the National Parks. Alfred A. Knopf, New York.