Last updated: January 13, 2026

Article

2024 Coastal Waterbird Monitoring Season at Boston Harbor Islands National and State Park

NPS Photo/ E. Deino

Monitoring highlights

- We had 16 volunteers and 5 partner agency staff join us this season, many of them returning from previous years!

- We only had a few weather delays, and we were able to land on every island that we intended to survey.

- We had some unexpected bird visitors on the islands: Black Guillemots, a Yellow-crowned Night Heron, Surf Scoters, Laughing Gulls, a Magnolia Warbler, and a Great Cormorant.

- We found a Herring Gull on Calf Island that was banded as a chick in York County, Maine!

Why monitor birds in the Boston Harbor Islands?

Regardless of where you live, work, and play, it’s almost certain that you have seen at least one bird this week. Though most of us have become numb to their presence, birds are everywhere. In fact, birds can be found in almost every habitat in the world — even in the most extreme places. A few examples include the penguins in frigid Antarctica or the ostriches in the sub-Saharan desert.

The omnipresence of birds and their ability to adapt to different conditions makes them a great indicator species. An indicator species is an organism that reflects changes in the environment they live in. By monitoring waterbirds at the Boston Harbor Islands, we can determine the health of the ecosystem, which allows us to make informed management decisions.

NPS Photo/ E. Deino

The Boston Harbor Islands National and State Park is an Important Bird Area (IBA) that is utilized by a large number of colonial-nesting waterbirds. These 34 islands and peninsulas offer lots of nesting habitat, from shorelines to vegetated interiors and weathered cliffs.

Rocky shorelines are a favored nesting spot for American Oystercatchers, a high priority shorebird species with high conservation concern in the U.S. Tall shrubs on Outer Brewster Island and Sheep Island provide nesting habitat for locally uncommon wading birds like the Black-crowned Night Heron and the Glossy Ibis. Low shrubs and grasses offer ideal nesting habitat for the Common Eider – a northern sea duck species – while steep cliffs host breeding colonies of cormorants and gulls. Even a little old platform on Spinnaker Island hosts a breeding colony of Common Terns, a species of Special Concern in Massachusetts.

The goal of the coastal waterbird monitoring program is to improve our understanding of the status of bird populations in the harbor. Threats to nesting waterbirds include predation, human disturbance, climate change, and invasive plants. This program enhances our regional knowledge of factors affecting waterbird populations to ultimately support their long-term conservation and encourage community involvement in the park.

NPS Photo/ R. Vincent

How do we monitor coastal breeding birds?

Since 2007, the National Park Service has partnered with participatory science volunteers to conduct bird surveys of the Boston Harbor Islands. In early summer, we take boat trips to the outer islands and conduct incubation surveys of nesting gulls and cormorants. During an incubation survey, we count every bird sitting on a nest to estimate the size of the breeding colonies on each island. Later in the season, our boat-based team surveys eider creches – groups of multiple females and their chicks. Grouping together as one big family unit allows these ducks to have strength in numbers!

NPS Photo/ S. Zendeh

NPS Photo/ E. Deino

2024 Monitoring Season Summary

This year was especially exciting because it involved ground counts of nests. Surveys begin in mid-May every year because this is historically when birds begin nesting on the islands.

Our first outing was on Monday, May 13. We boarded a small landing craft vessel at the University of Massachusetts Boston dock and started with a boat-based incubation survey, then landed on Great Brewster Island to count nests. Despite the occasional swells and wakes from passing cargo ships, everyone fared well with the help of ginger chews. Our first two weeks consisted of daily ground counts on different islands in the harbor. Thick vegetation and hot weather made for challenging days, but nothing beats being on an island with a view of the Boston skyline.

NPS Photo/ R. Vincent

Our last trips of the season were eider creche surveys. From early June until July, we spent our time on the boat doing a loop of the outer islands. During these trips, we circled each island and counted the number of eider chicks and females tending to each group of chicks. By the end of the season, many chicks had grown to almost the same size as the adults, so we had to rely on the presence of fuzzy downy feathers to count them.

My favorite moment was watching the eider chicks waddle off of a rock and plop into the water. Since eider evolved to dive for food, their feet are set at the far back end of their bodies. This makes it difficult for them to walk but results in primetime entertainment for us humans.

NPS Photo/E. Deino

2024 Findings

The Boston Harbor Islands do not stand still. Storms, human activity, transient creatures moving between islands, and passing time are some of the reasons these island habitats are ever changing. This means the species utilizing these spaces are dynamic as well, making it no surprise that we found notable changes in bird populations this year.

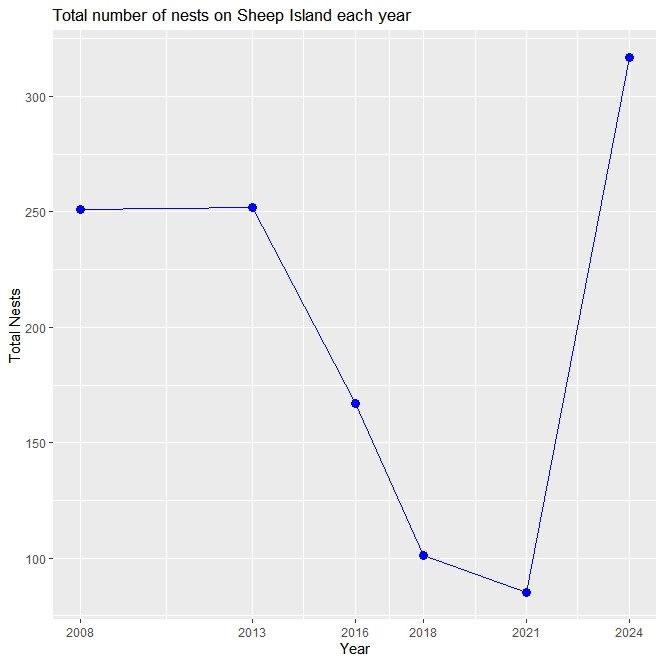

In 2024, we counted almost 3 times as many Double-crested cormorant nests on Calf Island than we had in 2021 (154 nests in 2024 vs. 55 nests in 2021). Within the inner harbor, we counted 317 nests from 9 bird species on tiny Sheep Island. That is the highest number of nests we have recorded on Sheep Island since our first survey in 2008.

E. Deino

On even smaller Hangman Island, where it only took us 15 minutes to survey the land, we were surprised find 3 oystercatcher pairs sharing the space! This high density of oystercatchers may indicate abundant food. Additionally, as strong storms are becoming more frequent, the inner harbor’s shielded habitats may offer more appealing protection from the elements, attracting more nesters.

While it is extremely valuable to know which islands serve as bird breeding grounds, we also consider where birds are nesting within each island. This season, we plan to plot the nesting locations of certain species. This will allow us to visualize the areas on the islands that are most important to nesting waterbirds.

The data collected this year is a snapshot of what the Boston Harbor Island birds have been doing for just one season. When many years of these snapshots are examined together, they begin to tell a story. Years of effort from NPS staff, partners, and dedicated volunteers are what allow us to see trends and make management decisions. The continued monitoring of these birds allows us to consistently update the story and steward the ever-changing landscape of the Boston Harbor islands.

Contributed by: Emilia Deino, Scientists in Parks Intern

Learn More

Coastal Bird Monitoring in Northeast Temperate Network Parks