Last updated: September 15, 2021

Article

19th and 20th Century History of Saint Croix Island IHS

NPSPhoto/Albrecht

Nineteenth Century in the Saint Croix Valley

In 1806, Township No. 5 was given the name Calais; in 1809 it was incorporated as a town, still as part of Massachusetts. Population in 1810 was 372. By 1820, the population of Calais was 418, and that of St. Stephen (Canada) was probably twice that number. After 1820, the region in general experienced a period of rapid growth. Calais’ population grew more than fourfold during the next decade, and St Stephen grew at a similar pace. By 1840, the population of Calais was 2,934. During the next decade the town nearly doubled again in size, and by 1850 it had surpassed its neighbor and become incorporated as a city. Calais continued to grow, albeit it at a slower pace, through the remainder of the century. By 1900 its population had peaked at 7,655 and that of St. Stephen numbered slightly over 2,800 (Canada, Dominion Bureau of Statistics 1953:6-6; Knowlton 1875:40-43, 47, 58, 18; U.S. Census Bureau of 1811:4a, 1921:324; Varney 1881:152).

Among the new settlers arriving in the area were a group of Celtic-speaking Highland Scots, who settled in St. Stephen in 1804 (Knowlton 1875:45). Many immigrants (especially Irish) arrived in New Brunswick and New England during this century. Although by 1881, Irish-Canadians made up the largest ethnic group in Charlotte County (>38%), records show that more than 89% of the county’s population was Canadian born, suggesting that immigration had slowed considerably by that time (Canada, Department of Agriculture 1882:222-223, 320-321). The Passamaquoddy people survived this period of rapid development, with 379 Passamaquoddies recorded in the Census of 1825 (U.S. Census Bureau 1853:379).

The century began with a boom in local lumbering, with the erection of new sawmills and increasing exports of timber products. Shipbuilding began at Township No. 5 (Calais) in 1803. The first roads were constructed at this time, including a road built in 1811 between Calais and Robbinston, that paralleled the south bank of the Saint Croix River passing by Saint Croix Island. The War of 1812 brought economic decline to the American side because of the British blockade. There was, however, no armed conflict between the people of Calais and St. Stephen, although small contingents of troops were stationed in each town. After the war, Calais recovered slowly. St. Stephen continued to prosper throughout the decade. Here, economic activity focused on agriculture, and was generally very successful (Knowlton 1875:52-54, 57-58).

After 1820, a renewed growth in the lumbering industry spurred further infrastructure development, housing construction, and population growth. Railroads connected Calais to other parts of Maine beginning in 1851, and linked St. Stephen to other parks of New Brunswick beginning in 1867. Shipbuilding continued to grow in both Calais and St. Stephen, with occasional periods of depression (Knowlton 1875:58, 161-162, 176-177). It was a thriving industry until in declined late in the century, as the era of “tall ships” came to an end (Isaacson 1970:287). Lumbering mills, axe and saw factories, and grain mills were in operation during the century. Other manufactures included bricks, bedsteads, brooms, and plaster.

Al Churchill

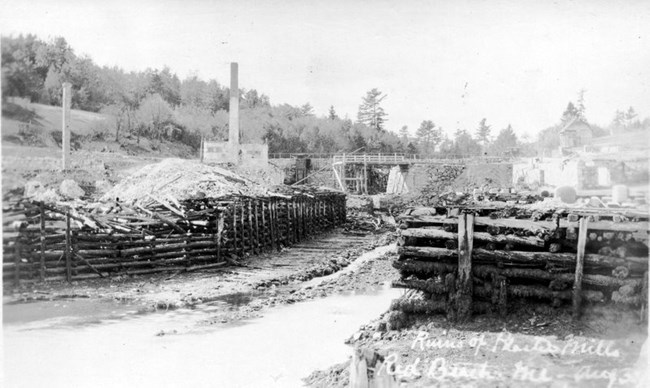

Red Beach Industrial Complex

In the mid-nineteenth century, an industrial and commercial center developed at Red Beach. Red Beach Cove, the site of the mainland tracts presently owned by the National Park Service, became the focus of much of this development.

During the latter part of the century, the Red Beach Plaster Company manufactured fertilizer and construction plaster at Red Beach Cove, near the site of the present interpretive plaque and picnic area. The company grew from a small mill in 1846, to a large operation employing as many as 100 workers in the late 1890s. Following this peak, the operation gradually declined (Johnson and Wilson 1976:13; Snell 1975:12).

A granite quarrying industry also developed at Red Beach and encouraged the growth of the village there. Granite quarrying began in the 1830s, and offices of several granite producing companies were located at Red Beach Cove. Locally, the most important of these was the Maine Red Granite Company, which was organized in 1876. The company built a polishing facility near the site of the plaster mill at Red Beach Cove (outside the NPS-owned mainland tracts). During its peak years it employed up to 60 workers, many of whom were immigrants from the Aberdeen area of Scotland, from England, and rom Ireland (Johnson and Wilson 1976:14, 17; Loendorf 1976; NPS 1977; Varney 1881:152).

As Red Beach and Calais became one of the major granite producing regions in Maine, workers and owners soon became embroiled in typical conflicts over wages and working conditions. The union movement grew in the 1880s and 1890s. A Knight of Labor lodge was formed in Calais in 1886; a Granite Cutters’ Union local was organized in Red Beach in 1890. Owners formed a Granite Manufacturers’ Association that same year. The struggle culminated in a lockout of Granite Cutters’ Union members in May 1892, which apparently broke the union (Johnson and Wilson 1976:20-21).

The nineteenth century was a very difficult period for the original inhabitants of the Saint Croix valley, the Passamaquoddies. Although their numbers slowly increased during this period, thousands of acres of their reservation land base were taken, including the islands in the Saint Croix River, despite the treaty that granted them these remnants of their homeland in perpetuity (Brodeur 1985:69-70; Continental-Allied 1972:5). During this period of exploitation, neglect, and discrimination, some Passamaquoddies continued fur trapping for a living. Others made baskets, axe handles, or other wooden utensils for sale, or hunted porpoise and other marine mammals in Passamaquoddy Bay. These activities continued to be important into the twentieth century (Michelson 1935:88; Erickson 1978:127, 129). Many men worked off reservation in logging or fishing. Small numbers of Passamaquoddy families lived in Calais, St. Stephen, St. Andrews, and St. George (Erickson 1978:125).

Saint Croix Island

By the beginning of the nineteenth century, Saint Croix Island was still most commonly referred to as Dochet Island, a name it had acquired during the previous century. Other recorded names of the island include “Neutral Island” (after 1812), “Great Island” or “Big Island” (after 1820), “Bone Island” (before 1831), and “Demonts Island” (after 1866). The Passamaquoddy name Muttanagwis was still used; it appears on an 1802 map of Maine (Ganong 1945:19-22; Snell 1975:9).

Records of permanent settlement on the island begin in the early years of the century with John Hilliker and his wife. The Hillikers did not own the island, and no buildings have been recorded in association with their occupation.

During the War of 1812, when British-American trade was prohibited, the island was used for smuggling. It was during this time that it became known as “neutral Island”. At that time, when Hilliker was living on the island, a wharf existed at Treat’s Cove, on the southwestern end of the island (Ganong 1945:20; Snell 1975:9-10).

In 1820, John Brewer of Robbinston, Maine, acquired the island. The Hilliker’s may have remained on the island as Brewer’s tenants. In 1826, Brewer sold the property to his brother Stephen Brewer of Northampton, Massachusetts. At the time of this transaction, there were a farmhouse, a barn, and other outbuildings, and a wharf on the southern portion of the island. These may have been built by the Hillikers (Ganong 1945:101). Stephen Brewer owned the land but did not reside on the island. Sometime between 1830 and 1855, the island was occupied by the Mingo family, who were fishermen, but also kept gardens and orchards on the island. The Mingos also built stages for curing fish on the island. Between 1839 and 1855 the Mingos left the island and it was inhabited by a resident named Treat (possibly also a fisherman), another named Chase, and later a resident named Thompson, who “kept there a sort of public house of low repute, to which people resorted from Calais and elsewhere” (Ganong 1945:102). Chase and Thompson demolished the outbuildings and possibly the barn for firewood. They were the last residents of the island before the construction of the lighthouse (Ganong 1945:102).

Stephen Brewer owned the island until his death in 1856. His heirs sold the northern portion of the island to the U.S. government in 1856, and kept the southern portion, with the house and other buildings, until 1869. At that time, the property was sold to Charles H. Newton, Joseph A. Lee, Herbert Bernard, and Benjamin F. Kelly. During this time, the island was used as a sand quarry. Some sand was taken from the northeastern part of the island; other sand may have been taken from the island’s southern end, where the sand is deeper. In any case, the quarrying appears to have ended by 1865. These men and their families would continue to own the southern portion of the island until 1967 (Snell 1975:10-11).

By the middle of the nineteenth century, Calais had become a busy port and the Saint Croix River had become a busy thoroughfare. In 1853 more than 1,500 vessels (not including steamboats) used the Calais harbor (and the Saint Croix River). The need for a lighthouse was recognized because the river was difficult and treacherous, especially at night and in the often foggy conditions on the river. Saint Croix Island in particular, which was in the center of the river, was the scene of many wrecks (Snell: 1975:16-17).

Saint Croix Historical Society

Lighthouse Constructed

The Saint Croix lighthouse was built in 1856. The house was a 1 ½-story wood frame building, 23 feet 8 inches (north-south) by 25 feet 8 inches (east-west), with a brick basement (later replaced by concrete), interior brick chimney, and a light tower at the southern end of the roof. In addition to the light house, a barn was constructed. This was a single-story wood frame structure standing on stone piers, measuring 25 feet 4 inches (north-south) by 16 feet 4 inches (east-west), and situated north of the lighthouse (Snell 1975:22-24, 38).

The lighthouse operated into the twentieth century with the exception of a ten-year period (1859-1869) during which it did not operate but may have remained inhabited. A porch and pantry were added to the north side of the lighthouse in 1888. Around the turn of the century, the lighthouse was extensively remodeled inside and out. A coal-fired furnace was installed, and a bay was added to the south side of the building. New structures were also built. An “Oil Building” was added in 1869 and demolished in 1892. A one-story wood frame boat house with an 80-foot slip was constructed on the west side of the island in 1885. A fog bell mounted on a wooden tripod was installed in 1887. A wood/fuel house was built in 1885 and a poultry/hen house was added before 1892 (Snell 1975:2, 21, 25-28, 31, 32, 38, 44).

Twentieth Century in the Saint Croix Valley

Today, the lower Saint Croix River Valley remains largely rural, with small urban centers at Calais and St. Stephen. The local economy now centered on fishing, blueberries, wood products, light manufacturing (e.g. shirts), tourism, recreation, and retail. The lumber industry that thrived in the nineteenth century declined since the turn of the century. This decline is reflected in Calais’ and Washington County’s shrinking population (Isaacson 1970:287; NPS 1977:4-5).

Red Beach’s industrial base has disappeared entirely. The Maine Red Granite Company began to decline early in the century and closed by the 1920s. The Red Beach Plaster Company after a slow decline, closed in 1926 when a fire destroyed the mill, company store, bridge, wharf, post office, and other buildings (Johnson and Wilson 1976:12-13, 23-34). In the mid-1960s, U.S. Route 1 was relocated to its present location, causing further destruction to the site. Today, some stone foundations in the Park Service property west of Route 1, and the remains of the wharves in Red Beach Cove are the only visible remnants of what was once a busy industrial and commercial center (Johnson and Wilson 1976:13).

For the first half of the century, Passamaquoddy people continued to be resilient in the face of individual and institutional racism and discrimination. For example, Native American Mainers were without voting rights in Maine elections until 1967 (Continental-Allied 1972:5). Despite repeated challenges, the tribe has endured, its population had tripled (1,200 in 1970 [Continental-Allied 1972]), and its language, traditions, and folklore have survived (Michelson 1935:85). Today, Passamaquoddy language, once prohibited, is taught in reservation schools. The tribe has reacquired large tracts of their homeland, and has become more successful in the blueberry industry, and in the production of cement and concrete (Brodeur 1985:131, 147; Erickson 1978:126, 134-135). A total of 3,369 tribal members are listed on the tribal census rolls today, with 1,364 on the Indian Township census and 2,005 listed on Pleasant Point census. Learn more about the Passamaquoddy people byvisiting their website.

Saint Croix Island

On June 25th, 1904, the 300th anniversary of the French settlement at Saint Croix was celebrated with ceremonies on the island.

Several alterations were made to the lighthouse and its surroundings during the early part of the century. Around 1905, the bell tripod was replaced by a wood frame bell tower. In 1906 a small brick oil house was built north of the lighthouse (this structure is still standing). The barn was enlarged in 1916 by the addition of a lean-to on the east side. A colonial-revival porch was added to the lighthouse’s west side and a loading dock to the east side in about 1920. The 1888 wood/fuel house was demolished in 1933, and sometime between then and 1949 a new hen house was built. Finally, in 1957, the lantern was removed from the lighthouse and placed in a “cubular” tower constructed a short distance to the south, and the lighthouse was closed (Snell 1975:2, 32, 33, 35, 37). In 1976, a fire destroyed the lighthouse, barn, and bell tower, leaving the boat house and brick oil house the only remaining structures on the island.

In 1949, Congress authorized that Saint Croix Island be dedicated as a National Monument. The next step in the process was acquisition of the property by the National Park Service from the U.S. Coast Guard, which owned the northern portion of the island, and the private owners of the southern portion. This was completed in a series of transactions over the next 18 years, during which time the mainland tracts were also acquired. During this time, preliminary archaeological testing as conducted on the island under the direction of Wendell Hadlock (Hadlock 1950; Harrington 1951). Saint Croix Island was formally dedicated as a National Monument on June 30, 1968 (Snell 1975:11-15). In the following years, large-scale excavations unearthed parts of the French settlement and its cemetery. More recently, the mainland tracts have been surveyed for significant archeological resources related to the granite and plater industry.

From:

From Archeological Overview and Assessment of the Saint Croix Island International Historic Site, Calais, Maine

By Eric S. Johnson

Works Cited and Researched

Brodeur, P.

1985 Restitution: The Lands Claims of the Mashpee, Passamaquoddy, and Penobscot Indians of New England. Northeastern University Press, Boston.

Canada, Department of Agriculture

1882 Census of Canada: 1880-1881, vol 1. MacLean, Roger, Ottawa.

Canada, Dominion Bureau of Statistics

1953 Census of Canada: 1951. Dominion Bureau of Statistics, Ottawa.

Continental-Allied Co., Inc.

1972 Passamaquoddy Indian Economic Development. Report Under Contract 0-35417, Economic Development Administration, Washington, D.C.

Erickson, V.O.

1978 Maliseet-Passamaquoddy. In Northeast, edited by B.G. Trigger, pp. 123-136. Handbook of North American Indians, vol. 15, W.C. Sturtevant, general editor. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

Ganong, W.F.

1945 Ste. Croix (Dochet) Island. Revised and Enlarged, Edited by S.B. Ganong, Monographic Series No. 3, The New Brunswick Museum, Saint John, N.B.

Hadlock, W.S.

1950 Narrative Report on Preliminary Exploration at St. Croix Island. On file at Acadia National Park, Bar Harbor, Maine.

Harrington, J.C.

1951 Preliminary Archaeological Explorations on St. Croix Island, Maine. On file at Acadia National Park, Bar Harbor, Maine.

Isaacson, D.A. (editor)

1970 Maine, A Guide “Down East.” 2d edition. Courier-Gazette, Rockland, Maine.

Johnson, R.W., and M. Wilson

1976 St. Croix Island National Monument: Cultural Resources Survey of Mainland Tracts, August 23-31, 1917. On file at Division of Cultural Resources, North Atlantic Regional Office, National Park Service, Boston.

Knowlton, I.C.

1875 Annals of Calais, Maine and St. Stephen, New Brunswick. J.A. Sears, Calais.

Loendorf, L.L.

1976 Mainland Area-St. Croix Island N.M. Cultural Resource Inventory. On file at Division of Cultural Resources, North Atlantic Regional Office, National Park Service, Boston.

Michelson, T.

1935 The Passamaquoddy Indians of Maine. Explorations and Field Work of the Smithsonian Institution in 1934 85-88. Washington.

National Park Service (NPS)

1977 Assessment of Alternatives: Comprehensive Design of Initial Development, St. Croix Island National Monument, Maine. On file at Acadia National Park, Bar Harbor, Maine.

Snell, C.W.

1975 Historic Structure Report: St. Croix River Light Station, Maine, St. Croix Island National Monument, Maine, Historical Data. Denver Service Center Historic Preservation Team. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. On File at Division of Cultural Resources, North Atlantic Regional Office, National Park Service, Boston.

United States Bureau of the Census

1811 Book 1 of the Third Census 1810. Washington.

1853 The Seventh Census of the United States: 1850. Robert Armstrong, Washington.

1921 Fourteenth Census of the United States Taken in the Year 1920, vol. 1. Government Printing Office, Washington.

Varney, G.J.

1881 A Gazetteer of the State of Maine. B.B. Russell, Boston.

You are able to enjoy the mainland site which has beautiful views of the island and is where the colonists built their gardens and a hand mill. You can also visit the mainland interpretive trail, viewing platform, and ranger station. If you're visiting Canada, you can also visit the Parks Canada exhibit about the St. Croix settlement in nearby St. Andrews, Canada.