Last updated: August 19, 2021

Article

“Wandering” Through Park Skies: How Peregrine Falcons Connect National Parks

Nathaniel X. Boëchat/Friends of Acadia

“Wandering” Through Park Skies: How Peregrine Falcons Connect National Parks

Birds are everywhere. From a greater roadrunner in the Arizona desert to a house sparrow in urban parking lots, bird species call virtually every type of habitat home. By being so adaptive, birds demonstrate the ways nature is intertwined across geographical spaces. No bird better represents how connected the world is than the peregrine falcon.

Historically used by kings for their hunting prowess, these raptors can reach speeds of 180 mph in pursuit of prey. That makes peregrine falcons the fastest animal in the world. Though usually only seen as small figure high in the sky, the raptor grow to 36 to 49 cm (14.2 to 19.3 inches) in length, about the size of an adult’s forearm. Peregrine falcons are one of the few raptor species which can be found nesting on every continent (except Antarctica), including within multiple national parks. Their name reflects their wide range; “peregrine” is derived from a Spanish word meaning “wandering.” From the skyscrapers of New York City to the Big Bend region of Texas, we can witness these raptors in a variety of environments. In doing so, we share an experience that connects national parks in unexpected ways.

Below are peregrine falcon stories from four national parks. Each are located in different habitats and geographical areas, but all are connected through the same raptor.

Will Greene/Friends of Acadia

Acadia National Park

Peregrine falcons have a long and turbulent history in Acadia National Park. Historically a common raptor, peregrine falcons have a story that reflects the ways in which humans both positively and negatively impact our environment. These impacts include the use of pesticides, causing declining numbers of peregrine falcons populations, and the consequent conservation efforts to reintroduce peregrine falcons to Acadia National Park.

Since at least the 1930s, peregrine falcons nested along the cliffs of Champlain Mountain and Valley Cove. There, the eastern subspecies of peregrine falcon, sometimes known as the “big-footed falcon,” uses the steep and tall cliff faces to protect their eyries (nests). These sites were two of the 500 nest locations throughout the eastern United States identified by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife (USFW) in the 1930s.

However, the widespread use of pesticides, specifically DDT, throughout the 1940s severely hurt peregrine falcon populations. Pesticides leaked into the soil and was carried by wind and rain into the ocean and other habitats, even those far from the treated fields. Smaller animals, like fish, became poisoned. And the more predators like falcons ate these small animals, the more poison they ingested. This process is called bioaccumulation. This DDT bioaccumulation caused falcons to lay eggshells that were too thin to hatch. By 1964, USFW conducted another breeding survey and found zero active nests in the eastern United States. Peregrine falcons had been extirpated (removed) from the area.

Will Greene/Friends of Acadia

Recovery

Conservation organizations launched captive breeding and reintroduction programs to bring peregrine falcons back. Wildlife biologists chose Acadia National Park's Jordan Cliffs as the first reintroduction site in Maine. Between 1984 and 1986, 23 captive-bred peregrine falcons were reintroduced at Jordan Cliffs. In 1988, Ganesh, one of the young hatched at the site two years prior, reappeared at the Precipice Cliffs. Although Ganesh returned each summer, successful nesting was not confirmed until 1991. For the first time since 1956, Acadia National Park had a successful wild peregrine falcon nest with 3 fledged chicks. Ganesh returned to the same site each year until 1999; meanwhile, peregrine falcons returned to nest at Jordan Cliffs and Valley Cove as well. As of 2021, all three nesting sites have fledged well over 100 peregrine falcon young.

Today, spotting a peregrine falcon inside Acadia National Park is part of a true conservation success story, one forged from the coming together of various environmental groups; non-profit, state and federal organizations, universities, and private falconers.

NPS

Big Bend National Park

In 1999, the peregrine falcon was removed from the federal endangered species list. However, with fewer than a dozen known nesting pairs in Texas, the falcon remains on the state’s endangered species list. The majority of peregrines in the state of Texas are found in the Big Bend region. Big Bend National Park encompasses 801,000 acres of desert, river, and mountain ecosystems. The Chihuahuan Desert landscape of Big Bend is broken by the Chisos Mountains, which create an elevation difference of about 6,000 feet from the river to the highest peak. Peregrines use the riverside bluffs and the high mountain cliffs for breeding sites. An incredible diversity of species inhabit Big Bend, providing a wide variety of food for peregrines, including doves, ducks, swallows, and high insect populations.

Peregrine falcons were first recorded in the Chisos Mountains of the park in 1901. The subspecies of peregrine found in Big Bend National Park is Falco peregrinus anatum. This species is of particular interest in the Chihuahuan Desert because the mild climate in this southern portion of their range may allow the birds to be permanent, non-migratory residents.

NPS

Monitoring in the Park

National Park Service policies require the protection and preservation of all state-listed endangered species and all species of concern, regardless of federal or state classification. To that end, peregrine falcons have been monitored annually in the park since 1971, even after they were federally delisted. Nesting peregrines are bothered by loud, inconsistent noises and nests may fail with too many interruptions. To prevent this, the East Rim of the Chisos Mountains is closed during the breeding season (February 1 through May 31), and motor boats are prohibited in all three river canyons.

Through the efforts of federal, state, and private agencies in Texas, peregrine falcons have staged a remarkable comeback since they were placed on the federal list in 1970. Superintendent Bob Krumenaker remarked, “The small population found in Big Bend National Park and the Rio Grande Wild and Scenic River represents most of the peregrine falcons found in Texas. We appreciate the continued public support and cooperation to protect these remarkable birds."

A life-sized bronze peregrine falcon sculpture, created by Texas artist Bob Coffee, sits on a platform outside the Chisos Mountains Visitor Center. Donated by Friends of Big Bend (now called Big Bend Conservancy), the statue commemorates the success of efforts to protect peregrine falcons in Big Bend National Park.

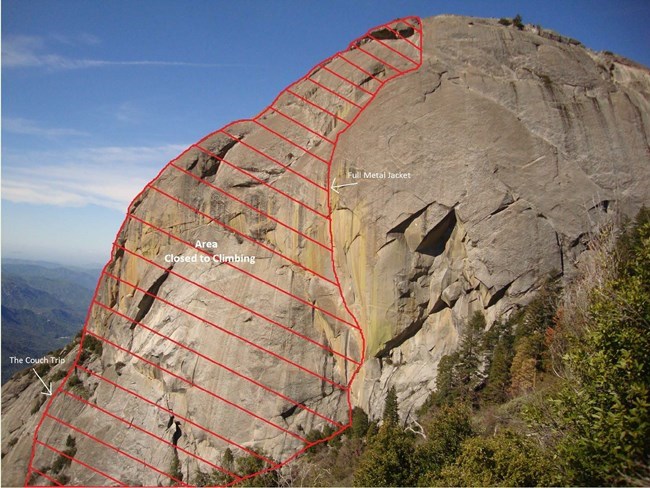

Sequoia National Park

The peregrine falcon has a special place in Sequoia National Park. It’s fitting that the fastest animal on the planet would live in a location full of superlatives like the General Sherman Tree, the world’s largest tree by volume. Although their population has fluctuated due to DDT, these birds have historically nested on a granite dome called Moro Rock. These fast flyers have made a comeback, nesting on this 6,725-foot-tall rock from roughly April to August. Visitors can climb the 350 carved granite steps for a panoramic view and a chance to see these powerful birds.

The peregrine falcon is a tough bird to see from the top of the rock, where numerous other bird species will flock over the foothills below. The air quality does not help this case, as Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks have poor summer visibility due to the smog levels. This air pollution is another major hazard for our fast friends.

Peregrine falcons mate for life and nest in the same location year after year. These birds return to Sequoia for around 5 months out of the year. Whether they are perched on their nest or flying to survey the land nearly a mile below, it's always an exciting experience to glimpse one of these amazing creatures while also taking in the views of the snow peaks of the Western Divide.

Statue of Liberty National Monument

The Statue of Liberty is just one of many New York City sites used by peregrine falcons. These sites include many skyscrapers and large bridges throughout the metropolitan area. Liberty Island is unique in that the human activity is abundant -- when in full operation, around 20,000 people visit Liberty Island each summer day and 4.5 million visitors come each year.

There are many reasons why this national monument is a magnet for peregrine falcons. First and foremost, the vast height of this metal and stone structure mimics the natural, high-altitude cliff habitat that the bird adapted to over the millennia.

Most visitors here never see peregrine falcons because these birds perch where people can’t go. These perching areas include: the torch flames, the rays of Liberty's nimbus, atop her Gibson Tuck hairdo, on her left shoulder, on the tablet’s Roman numerals, on her left index finger, on the folds of her stola (dress), and on the ledges and columns of the granite pedestal. Their spectacular flights often command attention, especially during their active period, January (when they stake out their territory) through April. The breeding season lasts from February to early April. Another reason for the falcon's fondness of Liberty Island is readily available and varied prey. The island is located in a migratory corridor where these falcons can hunt insects, anadromous and catadromous fish, bird species, and marine and airborne mammals.

Peregrine falcons primarily hunt bird species like rock dove, mourning dove, American woodcock, and northern flicker. Their diet also includes various species of bats drawn to the abundance of insects attracted to the electric lights that illuminate Lady Liberty each evening.

A Close Encounter

Statue of Liberty Park Ranger Jim Elkin shares, “During my nearly three decades as a Park Ranger at this National Monument, I have had some close encounters with peregrine falcons. One summer day many years ago, around 4:00 pm I wanted to share with some new staff a unique wildlife moment to behold. A red bat was flying in a repeated oval pattern around the Liberty Island Main Mall. At the same time, a pair of peregrine falcons were perched together atop the head of Liberty. Suddenly, one leaped off and went into a rocket-fast swoop. At the moment the red bat passed by just inches from my head, peregrine talons clenched the unfortunate bat as I felt the deflected gust from the raptor's wings stream across my face. Without landing, the peregrine blasted back atop the Statue of Liberty's head next to its mate to devour its prey in six quick bites.”