Last updated: October 29, 2020

Article

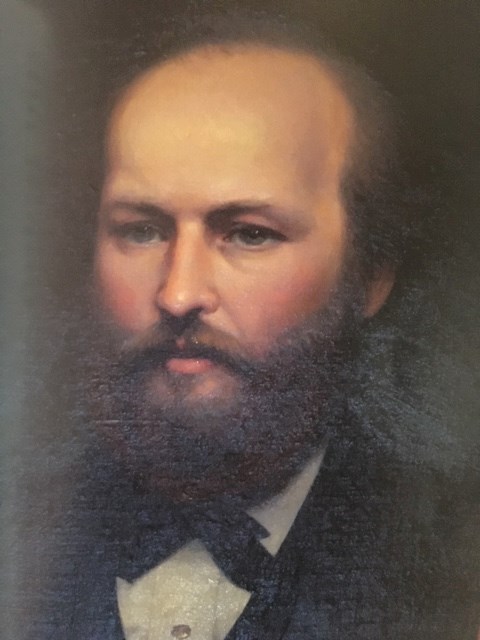

“This is the Age of Statistics”: James A. Garfield and the 1870 Census (Part I)

NPS

“This is the age of statistics.”~James A. Garfield, April 6, 1869.

In the summer of 1869, a political opponent mocked the congressman from northeast Ohio. Garfield, he said, had “gone mad on the subject of statistics.” Indeed, he had. As a rising member of the House majority, Garfield was tasked with chairing a subcommittee to prepare a legislative plan for the upcoming 1870 census of the United States. Not only was the census act of 1850 outdated, including a requirement that slaves be enumerated, it provided little information about the people it was tasked with counting.

“When we propose to legislate for great masses of people, we must first study the great facts relating to the people; their number, strength, length of life, intelligence, morality, occupations, industry and wealth, for out of these spring the glory or the shame, the prosperity or the ruin of a nation.” In a long speech in the House of Representatives (Garfield said he was allotted thirty minutes; in his collected works it runs thirty-three pages), the congressman put forward an ambitious legislative plan for the upcoming census that would meet the needs of a nation recovering from civil war, expanding geographically, and growing in industrial and commercial output. It contained specific recommendations for census questions.

On the most important part of the census, counting the population as required by the Constitution, Garfield had several suggestions. With slavery abolished, only one population schedule was needed. There was a question about color which included, for the first time, identifying Chinese as a separate racial category. This section also inquired into the education levels of the respondents, and attempted to gauge the physical well-being of the people. As Garfield said in his speech, “The war has left us so many mutilated men, that a record should be made of those who have lost a limb, or have been otherwise disabled; and the committee have added an inquiry to show the state of public health, and the prevalence of some of the principle diseases.”

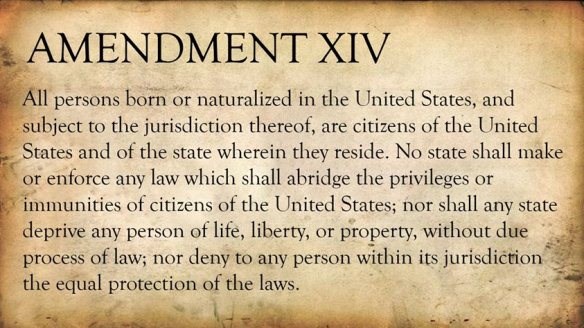

Garfield went on to point out that the addition of the 13th and 14th Amendments to the Constitution required changes in the ways census data was to be collected. Each black family needed to be enumerated, rather than counting enslaved people reported by their owners, and then reducing their number by two fifths. The 14th Amendment required that the voting population of men over twenty-one years of age would be reduced for purposes of representation, if any part of the population was denied the right to vote for reasons other than rebellion or conviction of a crime. In order to determine that number, the census was the only tool available to the government. Therefore the Census Committee identified nine different categories of exclusion from the ballot box—things like race, literacy, property ownership, or non-payment of taxes—that could violate the provisions of the 14th Amendment and reduce the representation in Congress of states that imposed those rules. Garfield admitted, “It may be objected that this will allow the citizen to be a judge of the law as well as the fact, and that it will be difficult to get true and accurate answers; I can only say this is the best method that has been suggested.”

Beyond the population census, Garfield and his committee recommended additional schedules to gather statistics about industry and commerce, and social statistics relating to schools and colleges, libraries, newspapers and periodicals. As with the population schedules, the committee saw these queries as important in measuring the growth and well-being of the country five years after the end of the Civil War. Garfield harkened back to the language of the war in his closing argument to the House of Representatives:

The Ninth Census of the United States will be far more interesting and important than any of its eight predecessors. Since 1850, in spite of its losses, the republic has doubtless greatly increased in population and wealth. It has taken a new position among the nations. It has passed through one of the most bloody and exhaustive wars in our history. The time for reviewing its condition is most opportune. Questions of the profoundest interest demand answers. Has the loss of nearly half a million young and middle-aged men, who fell on the field of battle or died in hospitals or prisons, diminished the ratio of increase in the population? Have the relative numbers of the sexes been sensibly changed? Has the relative number of orphans and widows perceptibly increased? Has the war affected the distribution of wealth, or changed the character of our industries? And, if so, in what manner and to what extent? What have been the effects of the struggle on the educational, benevolent, and religious institutions of the country? These questions, and many more of the most absorbing interest, the census of 1870 should answer.”

As excited as he was about the power of statistics in informing legislation, as persuasive as he could be in his presentation to his colleagues, Garfield was not preaching to the choir. The possibility certainly existed that the information the census produced could disprove politically popular preconceived ideas. Perhaps even more important to many in Congress, Garfield recommended removing the task of census taking from marshals and their deputies—patronage appointments coveted by almost all politicians—and putting the task to an independent, non-partisan Bureau of the Census. As the congressional session neared its end, Garfield saw that his proposal was likely to be amended beyond recognition, or defeated outright. So he accepted an amendment that effectively tabled the legislation and appointed a special committee to prepare a revised bill ready for introduction to Congress in the fall. Congressman Garfield would spend the summer in Washington with his committee, rather than at home in Ohio with his family.

(Look for Part II soon!)

Written by Joan Kapsch, Park Guide, James A. Garfield National Historic Site, August 2019 for the Garfield Observer.