Last updated: October 28, 2020

Article

“The Most Impressive Funeral Ever Witnessed”: The Funeral of President Garfield

White House Historical Association

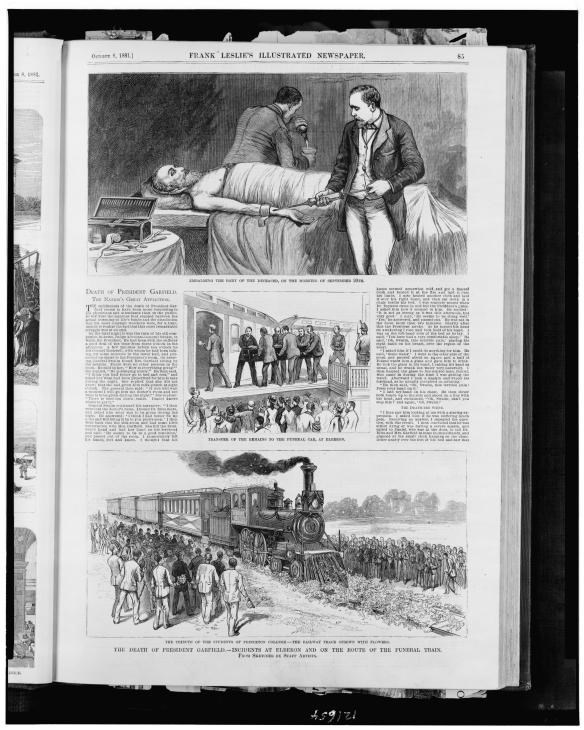

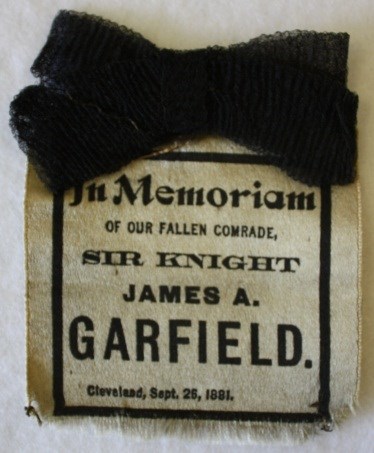

James Abram Garfield died at about 10:45 on the evening of September 19, 1881, 200 days after he had been inaugurated the 20th President of the United States. At his bedside at a seaside resort in Elberon, New Jersey, were his wife, Lucretia, and his daughter, Mollie. A few close friends and a number of doctors were also in the room. Garfield’s older sons, Hal and Jim, were at Williams College in Massachusetts, and the younger boys, Irvin and Abram, were at home in Mentor, Ohio with an aunt and uncle. His 80-year-old mother, Eliza, had been in northeast Ohio for the past three months staying with family members.

The President had lingered eighty days since the shooting, and newspapers across the country carried reports of his condition day by day. The whole nation had watched, waited, and prayed with the family. When it was over, they knew how to behave. Twenty years earlier the nation had been torn by civil war, and more than 700,000 Americans had died. And sixteen years before Garfield’s death the nation honored and buried its first assassinated president, Abraham Lincoln. America had learned a lot about mourning.

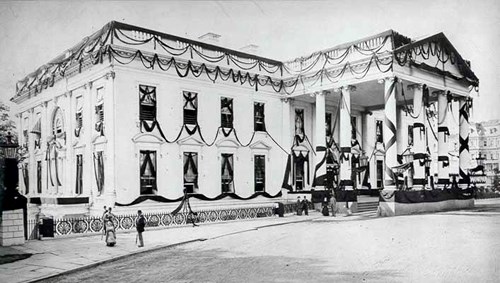

On September 20, 1881, the 20th President’s body returned to Washington, D.C. on the same train that had transported him to Elberon fourteen days before. Garfield’s oldest son, Harry, had joined his mother and sister in New Jersey and accompanied them on the journey to the capital. All along the route mourners stood at trackside, heads bowed as the train went by and church bells tolled. Bridges and buildings were draped in black. At Princeton, New Jersey, students scattered flowers on the track and then retrieved the crushed petals after the train had passed to keep for souvenirs. The train was met in Washington by the Chief Justice, Garfield’s entire cabinet, and Presidents Grant and Arthur. The President’s coffin was borne to the Capitol to the beat of muffled drums. The Rotunda was draped in black and piled high with flowers. Over 70,000 people waited in line for up to three-and-a-half hours to walk past the open coffin.

At eleven o’clock in the morning on September 23, the rotunda was emptied and Lucretia Garfield spent a lonely hour with the body of her husband of almost 25 years. When her vigil ended, the coffin was closed and would not be opened again.

At three o’clock, the memorial service began. Seventy members of the House of Representatives formed a double line around the rotunda. They were followed into the hall by members of the Senate, cabinet members, and diplomats from around the world. Bible verses were read, prayers were offered, a choir sang. The main address was given by Reverend F. D. Power of the Vermont Avenue Christian Church—the church President Garfield and his family attended in Washington, DC. Mrs. Garfield and her children did not stay for the ceremony at the Capitol.

“Immediately after the close of the services, the floral decorations were all removed, except the beautiful wreath, the gift of Queen Victoria, which had been placed upon the head of the coffin when the lid was closed, and which remained there when the coffin was borne to the hearse, and will be upon it until the remains are buried. This touching tribute of Queen Victoria greatly moved Mrs. Garfield.” [Cleveland Leader]

Then the remains of the president were carried from the Capitol where he had served for almost 18 years, to the depot where he had been shot. The funeral train consisted of 7 cars. The engine and cars were festooned with flowers and palm fronds. All the brightwork was draped in black. Most of the trip home to Ohio was accomplished during the night, but every depot at every small town was appropriately draped with mourning and illuminated flags, and the townspeople stood at trackside to watch the train roll by. At one, a long line of Civil War veterans fell to their knees as the train passed. Pennsylvania coal miners came up from the pits to bear witness. Bonfires, cannon, and tolling bells marked the train’s passage.

A respectful twenty minutes behind the funeral train was a special train for legislators and other dignitaries who were accompanying the funeral party from Washington. A third train was crammed with reporters for the newspapers and magazines whose coverage had brought Garfield’s assassination and suffering to all those who now watched the funeral trains go by.

As the train approached Cleveland the crowds along the tracks got bigger. If she had looked out the train window, Mrs. Garfield would have seen people standing shoulder to shoulder in a solid line along the last two miles of its journey into the city. The funeral train arrived in Cleveland at 1:21 on the afternoon of September 24. Lucretia Garfield was escorted from the train by her son Harry and Secretary of State James G. Blaine. The coffin was borne by an honor guard of eight sergeants from the 2nd U.S. Artillery Company to the waiting catafalque at the city’s Monumental Park, now usually called Public Square.

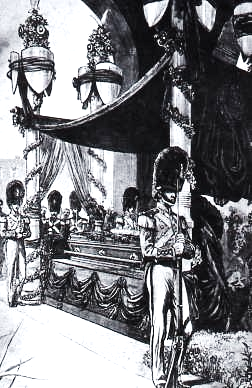

An elaborate pavilion had been built there, similar to the one that protected President Lincoln’s coffin when his funeral procession had paused in Cleveland on its way home to Springfield, Illinois. Described as “probably the finest temporary structure of the kind ever erected in America”, it was forty-five feet square, with a thirty foot archway on each side. From each of the pillars which supported the arches, a canopy stretched to a point seventy-two feet above the ground, where it was topped with a globe. A gilt angel stood upon the globe. Its wingtips hovered ninety-six feet above the square. The names of the states ran up the columns, and cannon, their muzzles draped in black, guarded each corner. The pavilion was filled with floral tributes, an estimated $3,000 worth—so many flowers that local supplies were exhausted, and boxcars of flowers were hastily delivered from Cincinnati and Chicago. None received more attention by the mourners or the press than the wreath sent by Queen Victoria, which rested on top of the coffin. A military honor guard stood at stiff attention around the casket.

On Sunday the catafalque was opened to the public. The line of viewers sometimes stretched for more than a mile. While the Marine Corps band played the Garfield Funeral March, Safe in the Arms of Jesus, and Nearer My God to Thee, the procession filed through the pavilion six abreast—a brisk 140 people a minute. They came all day, through the night and into the morning of Monday, September 26.

An estimated 250,000 people came into Public Square to see the pavilion, and perhaps have a chance to walk past the coffin to pay their mournful respects. Cleveland’s population in 1881 was 150,000.

The procession through the pavilion was stopped at 9:00 a.m. and the funeral service began promptly at 10:00 a.m. It was hot and sultry. The mourners included 18 senators, 40 congressmen, former president Rutherford B. Hayes and future president Benjamin Harrison. There were also governors, mayors, generals and admirals, including General Winfield Scott Hancock, the man Garfield had defeated in the presidential election just 10 months before. When all the dignitaries were seated, the Garfield family took their places. The president’s mother knelt briefly beside the coffin before joining the others.

The services began with the Episcopal burial service, followed by hymns and prayers. The eulogy was delivered by Isaac Errett, a Disciples of Christ minister who had been Garfield’s friend for many years. He took as his text: “And the archers shot King Josiah, and the King said to the servants, have me away, for I am sore wounded.” As he finished his sermon, Errett wept openly; so did a number of the mourners. After one more hymn and a benediction, the coffin was carried by ten soldiers to a funeral car, and the mourners took their places in carriages for the procession to The Lake View Cemetery, five miles to the east.

NPS Photo

The funeral car was heavily draped in black, showing no touch of color except for the white-tipped plumes bobbing from the heads of the twelve black horses that drew the car up Euclid Avenue. All along the avenue, people stood at solemn attention, reportedly ten to twenty people deep. The porches and windows of the grand mansions were full as well.

The ceremony at the cemetery was brief. A short oration was delivered by J. H. Jones, chaplain of the 42nd Ohio Volunteer Infantry, the unit Garfield had recruited for Civil War service and commanded for a time. The final benediction was offered by Burke Hinsdale, once Garfield’s student, and his life-long friend.

The coffin was placed in a flower-laden vault guarded by soldiers.* The Boston Globe called it “the most impressive funeral ever witnessed in America.” Newspaper accounts put its cost at $247,650. The verifiable expenses were about one-sixth of that.

*This was not the current Garfield Monument in The Lake View Cemetery that can be visited by the public. Garfield’s body was in a temporary crypt until being placed in the completed Garfield Monument, which was dedicated on Memorial Day 1890.

(Special thanks to Dr. Allan Peskin, whose article “The Funeral of the Century,” Lake County Historical Quarterly, September 1981 formed the basis for this post.)

Written by Joan Kapsch, Park Guide, James A. Garfield National Historic Site, September 2012 for the Garfield Observer.