Last updated: January 23, 2021

Article

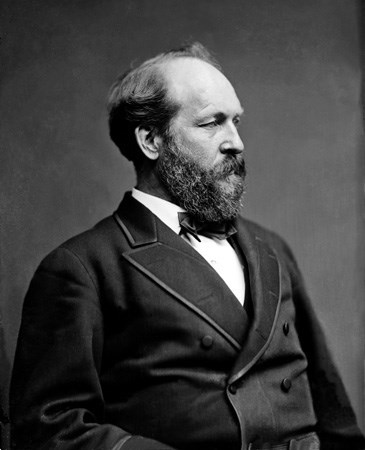

“It Bristles with Law Points”: James A. Garfield’s Career as a Lawyer, Part II

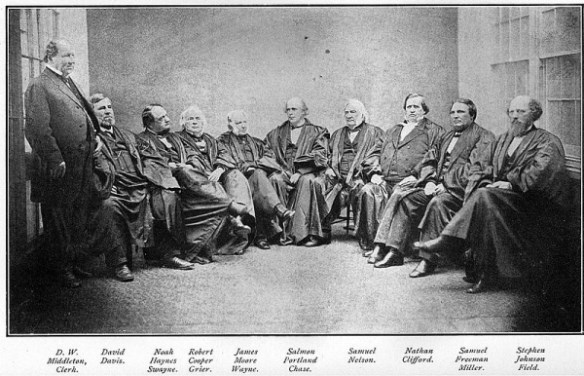

U.S. Supreme Court

Throughout his congressional career, Garfield maintained an active part-time law practice. Following his spectacular debut with the Milligan case, biographer T.C. Smith states, “He had patent interference and infringement cases, lawsuits for civil damages, suits involving the interpretation of the powers of territorial governments and suits involving the fulfillment of contracts.” Eleven of those cases were before the Supreme Court. Garfield saw his legal work as an intellectual challenge, and an important way to supplement his income. Writing to a friend in the spring of 1871, Garfield reported, “In addition to my Congressional work I have kept up and increased my law practice in the State courts and in the Supreme Court of the U. S. and have, from that source realized about $2000 a year for the last four years.”

Other cases arose out of the Civil War. In 1870, again before the Supreme Court, Garfield argued In re Bennet vs. Hunter. At the beginning of the war, Congress passed a law “for the collection of direct taxes in insurrectionary districts within the United States” in order to raise revenue for the war effort. The law stipulated that if the taxes could not be paid, the land would be forfeited and sold by the government. B. W. Hunter owned a tract of land in Alexandria, Virginia upon which a tax was levied in 1862. Mr. Hunter died, his son, a Confederate soldier, inherited, and the tax went unpaid. His property was advertised for sale in January, 1864. After the land was advertised, but before it was sold, Hunter sent a tenant to pay the full amount of the taxes owed, plus penalties. The tax commissioners refused to receive the money because it was not offered by the owner in person. So the land was sold, and Hunter sued. Since both the tax levy and the property sale were undertaken by the federal government, the case rose to the U. S. Supreme Court. In his argument in behalf of Mr. Hunter, Garfield made this appeal:

“The last time I had the honor to appear before this court you were then considering in the case of ex parte Milligan what were the rights of an American citizen on trial before the law. And you decreed that the shield of equal justice covered all the citizens of the republic, the highest and the lowest, the proudest and the humblest, the innocent and the guilty until found unworthy by conviction before a court of competent jurisdiction. You established the right to life and liberty. You are now called upon to make a similar decision relating to the rights of property which the law gives to every citizen of the Republic.”

Library of Congress

The Court endorsed Garfield’s position; Hunter’s land was restored to him.

Garfield described another case that arose from the war: “…It was a great question on the effect of war on a life insurance policy—whether it vitiated the insurance policy of a man who lived in the South, a belligerent. We took the ground that it did; it was a question that had never been tested in the Supreme Court. It was a new question.”

Because of the absence of one Justice, the Court failed to reach a decision, tying four to four. The next year a similar case brought by the New York Life Insurance Company rose to the Supreme Court and Garfield was retained by the company to argue both cases. All through the winter of 1875 Garfield prepared his arguments and briefs. The case was heard on April 26, 1876; the Court ruled in favor of the insurance companies.

National Park Service

Not every case Garfield handled involved a great constitutional question or a question of law in times of insurrection. Take for example the 1872 case of U.S. vs. 100 Barrels distilled spirits, aka Henderson’s Distilled Spirits. In accepting this case, Garfield said, “The amount in controversy is not large but it bristles with law points.”

The law in question, being a tax law, was long and exceedingly complex. Passed in July, 1866, the statute levied taxes on hundreds of products; it had seventy-one sections and covered “seventy-five large and closely printed pages of the statute book.” One of the sections addressed distilled spirits, levying a tax payable by the distiller before the liquor was sold or moved to a bonded warehouse. The distiller in this case, a man named Nimrod Johnson, deposited the 100 barrels of liquor at a bonded warehouse in New Orleans, but did not pay the taxes due. Henderson bought them, paid the tax, and transported the spirits to St. Louis where they were again placed in a bonded warehouse awaiting sale. It was there that federal agents seized the liquor, because Johnson had not paid the taxes he owed on it. Everyone involved in the case agreed that Henderson was an innocent and bona fide purchaser, and he won his case in federal district court. At the Supreme Court Garfield defended Mr. Henderson in a two hour oral argument and declared, “I am pretty well satisfied with the case as I have presented it.” He did not convince the Court, which ruled in favor of the government.

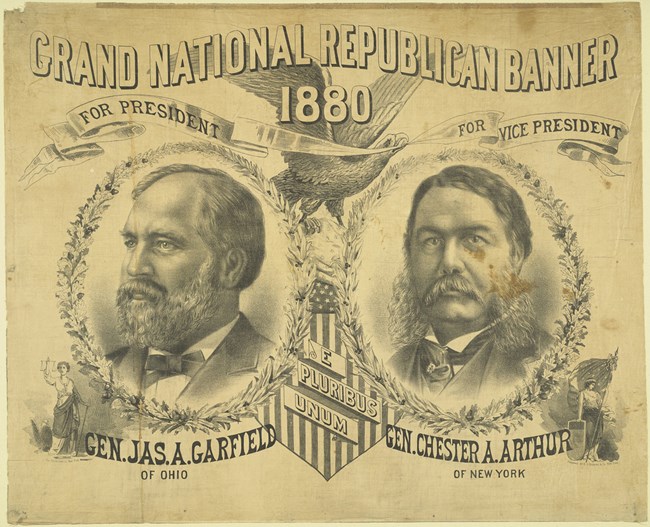

Several times during his nine terms in Congress, Garfield considered ending his political career for full-time law practice. Each time, a political or personal reason prevented him from making the change. In 1875 he worried in his diary, “My fear is that I have delayed too long…” and by the next year Garfield determined that his leadership position in the House required all his time and effort. He began to take new cases in 1879, as he saw the possibility of his House leadership ending and a less demanding Senate career beginning. His Presidential nomination in June of 1880 effectively ended James Garfield’s legal career.

Library of Congress

In his Eulogy on the Late President Garfield, delivered by James G. Blaine in the House of Representatives, February 27, 1882, Garfield’s colleague and good friend assessed the late President’s legal career with these words:

“As a lawyer, though admirably equipped for the profession, he can scarcely be said to have entered on its practice. The few efforts he made at the bar were distinguished by the same high order of talent which he exhibited on every field where he was put to the test, and if a man may be accepted as a competent judge of his own capacities and adaptations, the law was the profession to which Garfield should have devoted himself. But fate ordained otherwise, and his reputation in history will rest largely upon his service in the House of Representatives.”

Written by Joan Kapsch, Park Guide, James A. Garfield National Historic Site, May 2014 for the Garfield Observer.