Last updated: January 29, 2021

Article

“It Bristles with Law Points”: James A. Garfield’s Career as a Lawyer, Part I

Western Reserve Historical Society

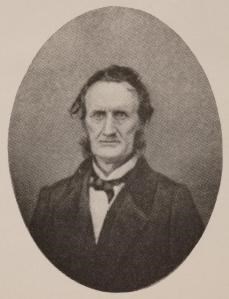

After two years of private study—while also teaching, regularly preaching, and campaigning for a seat in the Ohio Senate—James Garfield presented himself to a board of examiners seeking admission to the Ohio Bar. Following a “thorough and searching examination,” the board complimented his “unusual and phenomenal” mastery and admitted Garfield to the practice of law on January 26, 1861. Almost immediately the Civil War intervened and teacher, preacher, politician, lawyer Garfield became a soldier.

Yale University Law School

The Milligan case came out of the Civil War. Lambdin P. Milligan and four co-defendants had been arrested in Indiana in the fall of 1864 and charged with treason. Milligan and his southern-sympathizing friends were accused of plotting to release Confederate prisoners of war and giving aid to Rebel raiding parties in southern Indiana. They were tried by the army in a military tribunal, convicted, and sentenced to hang. They appealed, arguing that as civilians, they should not have been tried by the military in a state of the Union where civilian courts were operating. The case reached the Supreme Court in 1866.

Library of Congress

Garfield’s argument on behalf of Milligan and his co-defendants was lengthy and learned—he had spent weeks in preparation. He told the Justices that a ruling for the defendants would demonstrate “that a republic can wield the vast enginery of war without breaking down the safeguards of liberty; can suppress insurrection, and put down rebellion, however formidable, without destroying the bulwarks of law.” The Supreme Court unanimously agreed that the military did not have jurisdiction in the case, upholding Garfield’s position. Writing for the court, Justice David Davis said that the Constitution was “a law for rulers and people, equally in time of war and peace.”

Ex parte Milligan is recognized as one of the Supreme Court’s most important decisions about the rights of citizens to due process as outlined in the Constitution, and it gave Garfield instant recognition as a constitutional lawyer.

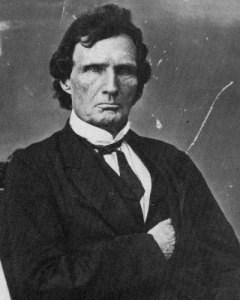

But Milligan was not decided in a vacuum. Immediately following the war, President Andrew Johnson, the Radical Republicans in Congress, and the people of the South were facing the issues of reconstruction. Following their overwhelming victory at the polls in 1866, Republicans in Congress, including James Garfield, quickly outlawed President Johnson’s very accommodating Reconstruction program. Fearing that essentially unreconstructed southern states would “substitute a degrading peonage for slavery and make a mockery of the moral fruits of northern victory,” Congress passed the First Reconstruction Act, establishing military rule in the former Confederacy. A feature of congressional reconstruction was a series of military courts established to maintain order and protect freedmen. President Johnson cited Milligan to oppose these courts. One of the most radical of the Republicans in Congress, Thaddeus Stevens worried that the Milligan decision, “although in terms perhaps not as infamous as the Dred Scott decision, is yet far more dangerous in its operation.” But Milligan did not address the appropriateness of the use of military courts in the states that had rebelled. Contrary to the fears of some that the decision by the Supreme Court had nullified at least a part of Reconstruction Act, what the Justices carefully declared was that military jurisdiction “can never be applied to citizens in states which have upheld the authority of the government, and where the courts are open”—exactly the argument Garfield had made.

Written by Joan Kapsch, Park Guide, James A. Garfield National Historic Site, April 2014 for the Garfeild Observer.