Last updated: September 10, 2020

Article

“If Any Outsider is Taken, I Hope it Will be Garfield”: The 1880 Republican Convention

http://www.grantstomb.org.

Every four years, America’s political parties hold national conventions to nominate candidates for President and Vice-President. Cities vie to host the event, and convention week is always full of rallies, parades, demonstrations and buzz. Until the second half of the 20th century, conventions actually did choose the presidential candidates. Nomination battles, now decided in primaries and caucuses, were fought out on the convention floor and in back rooms. Rumors flew, reporters listened, delegates caucused, supporters rallied. The sense of possibility and opportunity for surprise gave conventions a kind of excitement seldom seen in political gatherings today.

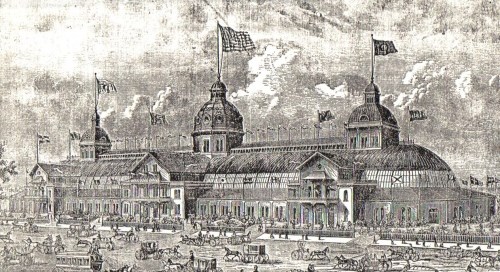

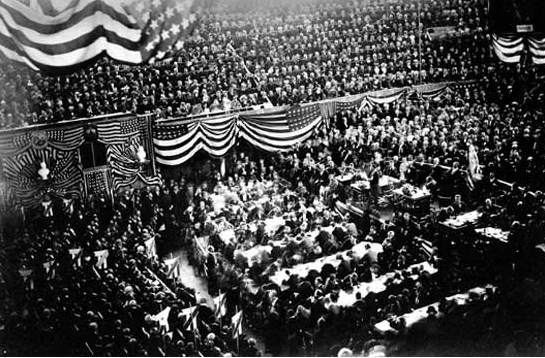

Republicans met for their seventh national convention in Chicago in early June, 1880. They convened in the brand new Industrial Exposition building, called the “Glass Palace” by locals for its enormous windows and skylights. It could hold 15,000 delegates, dignitaries and spectators. Some 500 reporters were provided tables right below the speakers’ platform where they could hear every word; they could report to the country by telegraph directly from the convention hall. Ladies filled the galleries while delegates settled under their state flags on the convention floor. The stage was set for the longest nominating battle in the history of the Republican party.

Puck Magazine Archives

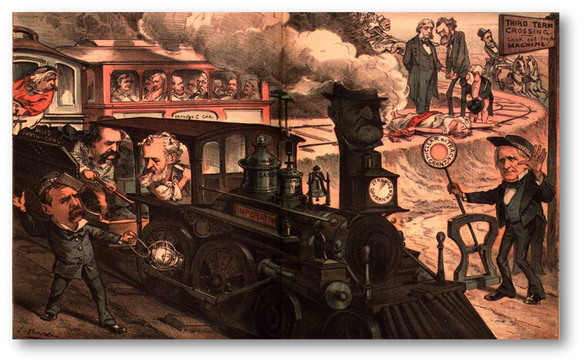

In 1880, the Republican Party had no clear leader. Rutherford B. Hayes (R., Ohio) was president, but his term in office was tainted by the bitter battle that put him there. He had announced that he would not seek re-election. U.S. Grant (R., Illinois) had been president before Hayes. He left office after two terms under a cloud of scandal. But he had just returned from a triumphal world tour and was anxious to return to the White House for a third term as President.

Unfortunately for Grant and his supporters, many Republicans remembered the graft and corruption of his presidency. Some opposed a third term for any president, though it was then allowed by the Constitution. When the Republicans held their convention in Chicago in early June 1880, Grant was supported by the largest bloc of delegates. But he did not have enough votes to win the nomination on the first ballot.

The “anybody but Grant” Republicans were led by Senator James G. Blaine (R., Maine). A smaller group, led by Congressman James A. Garfield, supported former Ohio Senator and current Secretary of the Treasury John Sherman. Several “favorite son” candidates were also nominated. The anti-Grant faction could not muster a majority for any one of those candidates.

Library of Congress

Delegates to the National Convention were chosen in state and local caucuses, and their votes were usually pledged to one or another of the candidates on the first ballot. Those votes had been counted and analyzed by politicians and newspapermen for weeks. On the eve of the convention the Albany Evening Journal reported that 277 votes were committed to Senator Blaine, former President Grant could count on 314 votes, Secretary Sherman had 106, and 49 votes were scattered among several “favorite son” candidates. With 379 votes needed to win, a first ballot victory for any candidate was unlikely.

But it was not impossible. The Grant forces at the convention were led by three important U. S. Senators: Don Cameron of Pennsylvania, John Logan of Illinois, and Roscoe Conkling of New York. They led three of the largest delegations at the convention, and if all three gave all of their votes to Grant, he could win on the first ballot. The delegations, however, were not unanimous. The three senators wanted the Republican national committee to invoke a “unit rule,” requiring that all the votes of a state delegation go to the candidate with the majority of votes from that state.

James A. Garfield, an at-large delegate from Ohio, arrived in Chicago on Saturday, May 29, 1880. The unit rule controversy met him as soon as he reached the city. He told a reporter for the Chicago Tribune that “all delegates…are political units, each one of which has a right to express his own political sentiment by his own personal vote…It is wholly un-Republican for one man to cast another man’s vote.” It was a principal of political autonomy that Garfield had held all his life and he told the reporter that for him it was “more important than even the choice of a candidate.” As an opponent of a Grant third term, and as chairman of the convention’s rules committee, Garfield spent the days before the convention opened working to block any attempt to impose a unit rule. Ultimately a compromise was reached that allowed all the delegates to vote on the question and the unit rule was defeated 449 votes to 306.

Two of the party’s best speakers were on hand to present candidates. Roscoe Conkling of New York nominated “the man who can’t be defeated—General Ulysses S. Grant!” It was a speech interrupted over and over with cheers and demonstrations, and most reporters agreed that if the balloting had begun right after Conkling’s speech, Grant would have won the nomination by acclamation.

James A. Garfield took the stage next to nominate his fellow Ohioan, John Sherman. He spoke calmly and thoughtfully, reminding the delegates that the presidential election would be decided “not in Chicago in the heat of July, but at the ballot-boxes in the Republic, in the quiet melancholy days of November.”

As the evening ended, one delegate told a reporter, “If any outsider is taken, I hope it will be Garfield. If Ohio wants a man, let Ohio ask for her best.” That same night James Garfield received a letter from his wife. “I begin to be half afraid that the convention will give you the nomination,” Lucretia wrote, “and the place would be most unenviable with so many disappointed candidates. I don’t want you to have the nomination merely because no one else can get it, I want you to have it when the whole country calls for you…My ambition does not fall short of that.”

None of the presidential candidates was in Chicago. Tradition demanded that they keep a seemingly disinterested distance while their political friends worked to secure the nomination for them. But the three major candidates were in close contact with their teams at the convention. Each had a dedicated telegraph line—Senator Blaine’s at his home on 15th Street in Washington, and Secretary Sherman’s to his Treasury Department office. Grant felt this was unseemly, so his neighbor in Galena, Illinois had a line brought to his home a few steps from Grant’s front door. With this rapid communication available, all three could be kept informed and send instructions to their forces in the convention hall. They could respond to events, propose strategies, and approve deals.

When the balloting began on Monday morning, June 7, none of the candidates was far from his telegraph. The first ballot brought no surprises: U.S. Grant had 304 votes, James G. Blaine 284 votes, John Sherman 93 votes, Elihu Washburn 30, George Edmunds 34, and William Windom 10 votes. The chairman of the convention announced, “No candidate having received the 379 votes needed to nominate, the clerk will call the roll for the second ballot.” By the end of the day twenty-eight ballots had been taken, and the vote totals had barely budged. Grant had 307 votes, Blaine had 279 and Sherman 91. One vote had been cast for James Garfield on the second ballot, by a delegate from Pennsylvania. That delegate continued to vote for Garfield on every ballot, but no others joined him that day.

Puck Magazine Archives

Overnight, all three campaigns met in private caucuses to plot strategy for the next day. Telegraph lines to Washington and Galena hummed with news and advice. Each camp was sure that a break by one of the others would lead to the nomination, so in the end none was willing to cede votes and the stalemate continued. They began Tuesday with the twenty-ninth ballot, but there was no real change in the vote totals until the very end of the roll call for the thirty-fourth ballot. When the clerk called Wisconsin, the chairman of the delegation stood on his chair to announce “two votes for General Grant, two votes of James G. Blaine, and (pause) sixteen votes for James A. Garfield!”

Garfield, at his place in the Ohio delegation, challenged the announcement, but was quickly overruled by the convention chairman. Telegrams flew to Sherman and Blaine. On the next ballot Indiana and Maryland switched their votes to Garfield. Blaine responded to his delegation and to Garfield, “Maine’s vote this moment cast for you goes with my hearty concurrence. I hope it will aid in securing your nomination and assuring victory to the Republican Party.” Sherman relayed this message: “Whenever the vote of Ohio will be likely to assure the nomination of Garfield, I appeal to every delegate to vote for him. Let Ohio be solid.”

It ended on the thirty-sixth ballot when Wisconsin announced its 20 votes for James Garfield. That brought his total to 399, 20 more than needed for the nomination. Garfield sat stunned. The convention hall erupted with cheers. Outside on the lakeshore, cannon were fired. As the clamor subsided, Garfield was able to compose a telegram to Lucretia: “Dear Wife. If the result meets your approval, I shall be content. Love to all the household. J.A. Garfield.”

Written by Joan Kapsch, Park Guide, James A. Garfield National Historic Site, August 2012 for the Garfield Observer.