Part of a series of articles titled Claiming Civil Rights .

Article

(H)our History Lesson: Women United, Mary McLeod Bethune and the National Council of Negro Women

This lesson was adapted by Katie McCarthy from the full-length Teaching with Historic Places lesson plan “The Mary McLeod Bethune Council House: African American Women Unite for Change.” For more information on this topic, explore the full lesson plan.

Grade Level Adapted For:

This lesson is intended for middle school learners, but can easily be adapted for use by learners of all ages.

Lesson Objectives:

Learners will be able to...

-

Describe Bethune’s goal of achieving equality for African Americans and explain the tactics she used to further this goal.

-

Describe how Bethune overcame challenges of racism and sexism and became an influential political activist.

-

Determine the central ideas or information of a primary or secondary source.

-

Identify aspects of a text that reveal an author’s point of view or purpose.

Inquiry Question:

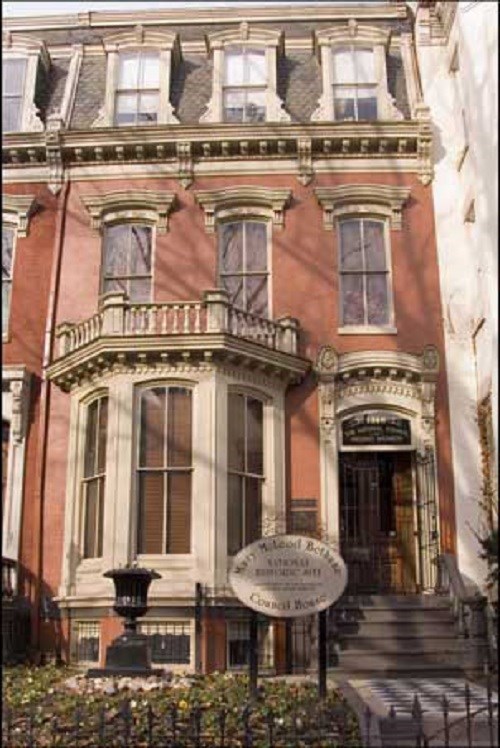

This image shows a gathering at the NCNW Council House. What kind of work do you think happened in this house?

Reading:

Background

The soft velvet rug that carpets the staircase that leads to the office of the president has felt the tread of many feet—famous feet and humble feet; the feet of eager workers and the feet of those in need; and tired feet, like my own, these days. I walk through our headquarters, beautifully furnished by friends who caught our vision, free from debt! I walk through the lovely reception room where the great crystal chandelier reflects the colors of the international flags massed behind it—the flags of the world! I go into the paneled library with its conference table, around which so many great minds have met to work at the problems of the past years. I feel a sense of peace. Women united around The National Council of Negro Women, have made purposeful strides in the march toward democratic living. They have moved mountains. Our headquarters is symbolic of the direction of their going, and of the quality of their leadership in the world of today and tomorrow.1

Mary McLeod Bethune wrote these moving words upon her retirement as president of the National Council of Negro Women (NCNW) in 1949. Bethune had founded the organization in 1935 to give African American women a collective national voice. As NCNW grew and gained respect, Bethune spearheaded the effort to establish a national headquarters. When a red brick townhouse in the Logan Circle area of Washington, DC became available, Bethune purchased it. As the first headquarters of the National Council of Negro Women, this house played a prominent role in advancing the causes of African American women around the country. From 1943 until 1966, it provided the setting for countless meetings. NCNW members discussed pivotal national events such as the integration of the military and public schools. They created and implemented programs to combat discrimination in housing, healthcare, and employment.

Bethune and the members of NCNW faced challenges of racism and gender discrimination with a tireless spirit and determination. Bethune helped give a voice to African Americans. She created an organization that continues to fulfill her vision more than 50 years after her death. Today the National Park Service cares for the headquarters as the Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site.

Content

Mary McLeod was born on July 10, 1875, near Mayesville, South Carolina. Racism was common in the post-Reconstruction South. Black children did not have many opportunities to attend school. Mayesville did not have a school for Black students until 1882. In 1885, Mary became the first member of her family to attend the new school. For the next several years, she walked five miles to the one-room school. Impressed by Mary's determination, her teacher chose her as the recipient of a scholarship to attend Scotia Seminary, a school for Black women in North Carolina.

After McLeod graduated in 1894, her benefactor paid for her to attend the Moody Bible Institute in Chicago. When she completed the program, she returned to Mayesville. She began teaching at her former school. Later, she moved to Augusta, Georgia, to teach at the Haines Normal and Industrial Institute. While there, she married Albertus Bethune, a clothes salesman. In 1904, the family moved to Daytona Beach, Florida. There, Mrs. Bethune opened a school for the children of poor Black laborers on the Florida East Coast Railroad. Although the school suffered through financial struggles, it was overall a success. In 1923, it merged with a college in Jacksonville, Florida, and became Bethune-Cookman College. Bethune remained president of the school until 1942, when she resigned in order to focus on her national agenda.

Mary McLeod Bethune's work as an educator led her to become an influential political activist. Throughout her career, Bethune assumed leadership positions in several African American women's clubs. She served as president of the National Association of Colored Women's Clubs (NACWC). This was the highest national position for a Black woman at that time. As NACWC president, she led the organization to focus on social issues facing all women and society in general. The group lobbied for a federal anti-lynching bill and prison reform. It also offered job training for women.

By the mid 1930s, Mary McLeod Bethune was a leader in the fight for African American rights. However, one of her goals remained unfulfilled. As early as 1928, Bethune raised the idea of forming a coalition of Black women's organizations. She felt that the NACWC did not focus enough on national issues relating to African American women. She strongly believed that when united, Black women could be a powerful force for promoting political and social change.

Bethune championed her cause for over five years. In December 1935 representatives of 29 diverse Black women's organizations agreed to establish the National Council of Negro Women (NCNW). With Bethune as its president, this new organization would provide a strong national voice on issues such as education, employment, health, and civil rights. She wrote, "The great need for uniting the effort of our women kept weighing upon my mind. I could not free myself from the sense of loss, of wasted strength, sustained by the national community through failure to harness the great power of women into a force for constructive action. I could not rest until our women had met this challenge."2

NCNW incorporated in Washington, D.C. on July 25, 1936. According to the organization's constitution, the four major objectives were:

-

To unite member organizations into a National Council of Negro Women.

-

To educate and encourage Negro women to participate in civic, political, and economic activities in the same manner as all other Americans participate.

-

To serve as a clearing house for the dissemination of information concerning activities of organized colored women.

-

To initiate and promote, subject to the approval of member organizations, projects for the benefit of the Negro.

NCNW members worked tirelessly to be included in national organizations and activities. Bethune contended, "Wherever women are working for good citizenship, social and economic welfare, community health, nutrition, child welfare, civil liberties, civilian defense and other projects for the advancement of the people—there also we must be…."3 Not surprisingly, the Women's Interest Section in the War Department in 1941 excluded NCNW, Bethune protested to the Army:

We are anxious for you to know that we want to be and insist upon being considered a part of our American democracy, not something apart from it. We know from experience that our interests are too often neglected, ignored or scuttled unless we have effective representation in the formative stages of these projects and proposals….We are incensed!4

The Army reconsidered and invited NCNW to become a member of the Women's Interest Section. This important victory helped NCNW become the nationally recognized representative of African American women as the country entered World War II. Throughout the war, NCNW found ways to express patriotism. The organization sponsored the construction of a Merchant Marine Liberty ship named the S.S. Harriet Tubman through the sale of war bonds. The ship was the first to honor an African American woman.

Bethune established an official headquarters for NCNW in 1944. She stepped down as president at the age of 74 in 1949. The headquarters provided a place to host social functions and conduct NCNW business. Distinguished guests from around the country and around the world visited the site. The Council House continued to provide a home for NCNW Until January 1966. NCNW continued to fight discrimination against African American women. It still exists as an organization today.

Reading Discussion Questions:

-

How was Mary McLeod able to attend Scotia and Moody Bible Institute? How do you think her education impacted her life and her desire to help others?

-

Why did Bethune found NCNW? What were its major goals?

-

What were some of the important issues that NCNW members worked to address?

-

Why do you think it was important that NCNW was recognized as a national organization and included in national conversations?

-

Why do you think it was important for NCNW to have an official headquarters?

-

What did the NCNW’s headquarters provide for the organization’s members? What kind of standing did it give the organization?

Activity:

Mary McLeod Bethune was a powerful orator, and those who heard her speak were often moved by her speeches. Have students listen to or read “What Does American Democracy Mean to Me?” a speech Bethune gave on November 23, 1939 during an NBC radio broadcast. After listening to or reading the speech, have students write a newspaper article dated the following day, analyzing and reviewing the speech. Students may consider the following questions while writing their article:

-

What seems to be the overall message Bethune is trying to convey in this speech?

-

What emotions or feelings do you think this article evoked in its readers? Which phrases or expressions do you think particularly inspired these emotions?

-

Who do you think was Bethune’s primary audience? Who was she trying to speak to?

-

Who is the primary audience of your newspaper article? How does that affect how you report Bethune’s speech?

Wrap-up:

-

What do you think motivated Bethune throughout her life?

-

Can you think of someone from your community who has fought for civil rights?

-

What do you find most interesting or impactful about Bethune’s life or work?

-

What does learning about Bethune’s life make you want to learn more about?

Footnotes:

1 As quoted in Audrey Thomas McCluskey and Elaine M. Smith, eds., Mary McLeod Bethune: Building a Better World: Essays and Selected Documents (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1999), 193.

2 Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site: General Management Plan (Washington, D.C.: National Park Service, 2001), 59.

3 Audrey Thomas McCluskey and Elaine M. Smith, eds., Mary McLeod Bethune: Building a Better World: Essays and Selected Documents (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1999)

4 As quoted in McCluskey and Smith, 174.

This reading was adapted from Andrea Broadwater, Mary McLeod Bethune: Educator and Activist (Berkeley Heights, NJ: Enslow Publishers, Inc., 2003); Dr. Bettye Collier-Thomas, NCNW: 1935-1980 (Washington, D.C.: The National Council of Negro Women, 1981); Audrey Thomas McCluskey and Elaine M. Smith, eds., Mary McLeod Bethune: Building a Better World: Essays and Selected Documents (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1999); Elaine M. Smith, Mary McLeod Bethune and the National Council of Negro Women: Historic Resource Study (Alabama State University, 2003); R. Brian Wright, The Idealistic Realist: Mary McLeod Bethune, The National Council of Negro Women and The National Youth Administration (Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University Master's Thesis, 1999); and Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site: General Management Plan (Washington, D.C.: National Park Service, 2001); Malu Halasa, Mary McLeod Bethune: Educator (New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 1989)

Additional Resources:

National Park Service

Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site

Visit the Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site website for operating hours, directions, and other information that will help you plan a visit. The site also provides information on the National Archives for Black Women's History.

The National Council of Negro Women

Today, NCNW consists of more than 39 national affiliates and over 240 sections. NCNW's website features information on the organization's history, mission, structure, and membership.

Bethune-Cookman University

The Bethune-Cookman University website includes a biography of Mary McLeod Bethune and a history of the school.

Tags

- women’s history

- women's history

- african american women

- mary mcleod bethune

- mary mcleod bethune council house national historic site

- civil rights

- shaping the political landscape

- teaching with historic places

- twhp

- hour history lessons

- educational activity

- women and politics

- african american history

- twhplp

- ga aah

- etc aah

Last updated: May 16, 2023